Making over Narrative:

Family Business

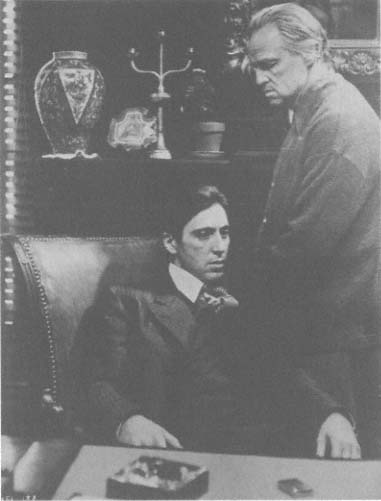

At the core of the fabula, or story, of both Godfather films is what Coppola's characters call the twin peaks of their lives: the personal ("family") and "business." Building on Puzo's novel, Coppola managed to infuse the Hollywood gangster genre with a richly textured double dose of the Italian American immigrant experience in the United States and the importance of family life to that experience. As Peter Cowie has observed about the first part of the trilogy, "[T]he film is really a paean, not so much to the Mafia as to the pioneer spirit that enabled generations of Italians to sail to the USA, settle, and establish a new caste of ironclad proportions" (53). (See figure 22.)

Note to what degree Coppola's two films exist not as prototypes for Time of the Gypsies but as complex examples of stories "based on stories already told." On the most immediate level, The Godfather is an adaptation of the novel with the added connection that the script was written by the novel's author. And Godfather II thus appeared as a sequel. A further exploration, however, would have to discuss Coppola and Puzo's "rewriting" of the cinematic genre of the crime film. It is just as important to our understanding of Coppola's films to know what kind of border crossing Coppola has done between the various films that make up the genre of previous mob-crime

Figure 22.

The godfather, Marlon Brando (with Al Pacino), takes the role of

the gangster patriarch far beyond the genre stereotypes

of the past in The Godfather (1972).

films as it is to study the process of adaptation from Puzo's written page to Coppola's moving images. Noting such a complexity in speaking about Hollywood cinema, Raymond Bellour has observed that "in the classic American cinema, meaning is constituted by a correspondence in the balances achieved. . . . Multiple in both nature and extension, these cannot be reduced to any truly unitary structure or semantic relationship" (99).

Acknowledging such a pluralistic state of balances and meanings within

Figure 23.

A Balkan family portrait: Perhan (Davar Dujmovic), far right, standing

next to his beloved grandmother (Ljubica Adzovic), is the young Gypsy

who later becomes a gypsy Mafia member in Emir Kusturica's Time of the

Gypsies (1989), a makeover of Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather .

Coppola's texts as, to one degree or another, makeovers of previous crime films as well as adaptations of a novel, we can now turn to Time of the Gypsies and the even more complex nature of the makeover.

Kusturica's saga follows a similar story-subject perspective—that of business and family. Time of the Gypsies is an epic chronicle of a young Serbian gypsy, Perhan (Davor Dujmovic), from awkward adolescence through puberty, young love, travel, involvement in a godfather-controlled crime network in Italy, and on to his eventual marriage, fatherhood, godfatherhood, downfall, and death.[1] (See figure 23.) Perhan's struggle, like that of The Godfather 's Michael Corleone, is between his strong sense and need of family and the pressures on him to go into the "business," in this case a crime empire dedicated to selling gypsy babies and exploiting cripples, dwarfs, and women (via prostitution) across the border in Italy (all based on true accounts of over thirty thousand gypsy children "sold" into such slavery by their parents and other relatives, a practice that has not ended). Beyond these plot and thematic similarities to the Coppola films, the differences mushroom in the fertile soil suggested by The Godfather and Godfather II .

For our purposes, I shall focus on both the cinematic (including narrative) and cultural differences that Kusturica's text evokes, with the addition of an extra observation: Part of the pleasure of Coppola's trilogy is that of watching the high level of professional acting, in many cases by actors such as Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, who began their film careers with impressive stage backgrounds. Kusturica, in contrast, has gone in absolutely the opposite direction, using predominately nonprofessional gypsies to play themselves, though the roles of Perhan and Ahmed especially are played by well-known actors.

If we embrace the totality of difference served us by Kusturica and his screenwriter Goran Mihic,[2] we could describe the fabula-plot of this Balkan makeover in the following way: Time of the Gypsies is a dramatic-comic tale told with both realism and dreamlike fantasy, full of cinematic references, concerning an Eastern Orthodox Serbian orphan gypsy with certain telekinetic powers who is raised within a matriarchal culture by his grandmother. He becomes a gypsy godfather but ultimately fails to mature due to the lack of a proper father figure. He finally tries to resolve his personal crises by murdering his adopted "godfather"-father and is in turn murdered by the godfather's latest bride. His dying expression, however, is not one of pain but is instead a satisfied smile as he sees a vision floating above him suggesting his dead mother, wife, and beloved pet turkey. Rather than a sense of loss, Perhan's death has brought him a deeper peace and seeming understanding. On a deeply spiritual level, he has been fulfilled.

Let us now explore more closely the nature and implications of Kusturica's makeover, beginning with the level of the cinematic border crossing.