Seven—

Raiders of the Lost Text:

Remaking as Contested Homage in Always

Harvey R. Greenberg, M.D.

You cannot speak "on" such a text, you can only speak "in" it, in its fashion, enter into a desperate plagiarism.

Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of The Text

In poker, when cards are poorly shuffled and redealt the result is often a "ghost hand." If the last hand was good, its ghost is likely to be a poor, watered-down thing better left unplayed. In their long Hollywood history, most remakes of earlier films have been ghost hands, shallow attempts to trade on an original's smash success by using new stars, new technology, sometimes a new setting—but the remake is rarely as profitable as the first movie and artistically is best left unmade.[1]

By no means is remaking necessarily dictated by pursuit of gain alone. The new version may be sincerely or ironically intended as homage or satire; it may be intended to open up psychological-political possibilities latent in the original movie that its makers were unaware of, or that could not be pursued because of censorship (e.g., Blake Edwards's Victor, Victoria [1982]—a remake of a now forgotten German film of the thirties with a much more suppressed homoerotic subtext).[2]

Steven Spielberg's purposes in rehashing the World War II chestnut A Guy Named Joe (1943) into Always (1990) would appear to be located well beyond the profit principle. That war has been the director's preferred locale in many of his pictures: 1941 (1979), two of the Indiana Jones cycle (Raiders of the Lost Ark [1981] and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade [1989]), and the underrated Empire of the Sun (1987).

Spielberg's father served as a radio operator with a B-25 bomber squadron in Burma as a young man (Tallmer, 1). Spielberg is proud of his parent's military career but has not spoken about any impact it might have had upon specific filmmaking choices. He clearly admires the hometown and frontline virtues commended by the media of the time—all that boyish spunk and good-humored doing without. He's been particularly enchanted by A Guy Named Joe since adolescence, has seen the film numerous times,

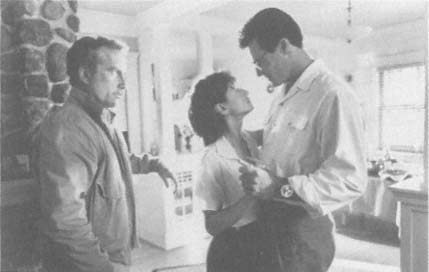

Figure 15.

An oedipal confrontation occurs, as teacher (Spencer Tracy), backed by his

sidekick (Ward Bond), faces student (Van Johnson) in A Guy Named Joe (1943).

and greatly admires its director, Victor Fleming. He says he's always wanted to make an old-fashioned love story like the one in Joe , instead of the action spectaculars that have been his hallmark (Steranho, 46).

A Guy Named Joe was actually a slight piece of business scripted rather lumpishly by Dalton Trumbo and redeemed by Victor Fleming's crisp direction. Daredevil pilot Spencer Tracy, madly in love with free-spirited air-person Irene Dunne, loses his life diving on a Nazi ship, then joins a spectral squadron of dead heroes with a mission to instruct a new generation of live ones. Tracy's prize student, Van Johnson, falls for Dunne. By the conclusion, Tracy has renounced his jealousy, recapitulating the renunciation theme privileged in Casablanca and other World War II movies. He proudly lets Dunne go "out of my heart" into a star-spangled future with Johnson.

Tracy's sidekick in A Guy Named Joe is the sturdy Ward Bond. (See figure 15.) John Goodman, as an oafish replicant of the sidekick character, Al Yackey, that Bond played, asserts at the beginning of Always that there's no good war to be found in contemporary America:

Figure 16.

Oedipal triangulation figures in Always (1989), as Richard Dreyfuss observes

Holly Hunter in the arms of Brad Johnson. Photograph by John Shannon.

AL: What this place reminds me of is the war in Europe . . . which I personally was never at, but think about it. . . . [T]he beer is warm, the dance hall's a quonset, there's B26's outside, hotshot pilots inside, an airstrip in the woods. . . . It's England , man, everything but Glenn Miller! Except you go to burning places and bomb 'em until they stop burning. You see, Pete, there is no war here. This is why they don't make movies called Night Raid in Boise, Idaho , or Firemen Strike at Dawn . And this is why you're not exactly a hero for taking the chances you take. You're more of what I would call—a dickhead.

As implied in Al's speech, Spielberg's enterprise is to have the war refought, but by brave pilots who put out raging forest fires with chemicals dropped from ancient planes, like the ones his father flew. There are such outfits, and they do run enormous risks. But the director reduces his relocated narrative to negligible sound and fury—roaring piffle unable to carry the weight of the original's perilous combat context.[3]

As leads, Richard Dreyfuss and Holly Hunter own all the sexual spark of Peanuts kids. (See figure 16.) They bed tastefully, without a jot of sensuality. Both are literally dwarfed by their earlier counterparts. Spielberg nods to feminism by using Hunter in a role that clearly means to reprise her feisty producer in Broadcast News (1987), much as he used Karen Allen in Raiders of the Lost Ark as a tough-minded foil for Harrison Ford. By the end

of Raiders , Allen had been reduced to an impotent screaming meemie. In Always , whether due to direction or scripting, Hunter's Dorinda has become a querulous tomboy. Dunne's read of the character is vastly more adult, competent, and sensuous on or off the ground. Intriguingly, her (and Tracy's) eroticism gains a keener edge from the implicit lack of consummation to their passion.

In Always , the couple's dialogue aims for the lucid sassiness of thirties and forties movies that conspicuously foregrounded equal footing between the sexes. But all too often lines reprise The Goonies (1985) rather than Adam's Rib (1949). Lacking the poignant edge of universal wartime insecurity, Dreyfuss and Hunter indulge inane New Age chatter about commitment, your thing, my thing, and so forth.[4] The oddly juvenile—and asexual—quality of their relationship infects Spielberg's work more definitively than ever, thoroughly subverting the unabashed romanticism of his project away from the bedroom as well.

In A Guy Named Joe , Tracy slow dances with Dunne at the officers' club, while a single flyer eyes her speculatively. In Always , at a dance in the fire-fighters' canteen, Hunter is besieged by a horde of grimy smoke jumpers who ogle and paw at her like moonstruck Boy Scouts. The sequence could have been filmed at sleep-away camp.

In the main, Always rates as an unfortunate ghost hand (about ghosts). The screenplay unwittingly telegraphs its own obituary via Yackey's admonition to Pete. Always is instructive about Spielberg's increasing blind spots: his childlike predilection for wretched excess, visually and aurally; his simple-minded admiration for male-bonded professionalism celebrated in the movies of Howard Hawks and John Ford; and, above all, his unreflective hankering—similar to Pete's—after what he evidently valorizes as an ideologically simpler era he never lived through (Spielberg was born in 1947) but chiefly experienced via its pop culture artifacts.

Essentially, Always interprets as a postmodern fantasy based on an agitprop version of the war—one cracked mirror held up to another, Baudrillardian simulacra both. Whatever its shortcomings, A Guy Named Joe did possess a substantive ideological agenda. The film sought to console audiences that their loved ones weren't really dead—merely translated to a newer realm of struggle (Kael, 92–93). It aimed at alleviating the guilt of women who found new men after their husbands or boyfriends had been killed. It virtually elided any notion of fear or panic in combat, purveying the message that no matter how rough the fighting got, an American soldier would still acquit himself with grace and good humor even as he died.[5] Finally, A Guy Named Joe strongly promoted the value of teamwork over rugged individualism. In a sense, Pete had to die to learn from his ghostly new compatriots that the war could not be won by a seat-of-the-pants soloist.[6]

Compared to its source, Always is radically drained of ideological freight.

Yackey's "dickhead" speech reads as a Barthesian "inoculation" against the recognition that practically nothing except tepid romance is at stake in this juvenile text with its infantilized characters.[7] Spielberg centrally privileges nostalgia and pastiche, that mimesis of dead styles from the "imaginary museum" addressed by Jameson and other cultural critics.[8]

The film is resolutely ignorant of or uncaring about actual history;[9] for all its feminist pretensions, its sexual politics are deeply, if unpolemically, conservative. It is profoundly informed by the "aesthetic frisson in emptiness"[10] so often encountered in recent remakes and sequels. I have elsewhere addressed the articulating psychosocial factors and film industry practices implicated in this monumental vacuity, which emerged during Hollywood's virulent pursuit of blockbuster profits in the late seventies and eighties (Greenberg, 1993).

My specific psychoanalytic interest in Always is the intensely rivalrous spirit inhabiting Spielberg's "homage." Harold Bloom (1973) has theorized that many of the strongest poets were compelled by their anxiety about a predecessor's power to deviate sharply from his praxis. Instead of employing Bloom's "swerve," Spielberg plunges unabashedly into A Guy Named Joe . The metaphor is literally fleshed out in the establishing sequence of Always, a peaceful scene of two men fishing on a lake. Behind them, a hug PBX seaplane descends. Its foreshortened image slowly fills the screen, wavering ominously in the lambent air, until the anglers, alerted by the sudden, terrifying roar of its engines, dive out of their canoe, barely escaping destruction as the plane swoops down upon them.

This arresting sequence is extremely difficult to place within the film's narrative schema. It can only be linked diegetically with an anecdote Dorinda-Hunter relates to her new lover more than halfway through the film, about a flying vacation she took with Pete-Dreyfuss in a PBX seaplane rigged as a "scoop" craft. From the air, Pete saw a fire in a small town court-house. He scooped up water from a nearby lake, dove upon the conflagration, completely missed the courthouse and disastrously flooded the town. Dorinda bubbles with laughter as she relates the episode. Her humor rings curiously callous for a character presented as so empathic, especially when one considers the misery that must have resulted from Pete's blunder.

The introduction may have been intended as a "raid" on audience sensibility reminiscent of the thunderclap establishing sequence of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977); perhaps the opening was also meant to anticipate Dorinda's tale about Pete's scooping water from the town lake. The connection in the conscious narrative between the two cinematic events is at best obscure. I suggest that this very tenuousness, along with Dorinda's unsympathetic humor, may be understood analytically as symptoms of an intriguing textual uneasiness, that it exemplifies strategies of isolation and crude denial, defenses against the occulted awareness within

the film's text of its own bristling competitiveness with the original narrative. Under this rubric, the men in the boat, the town, and its people can be taken as one entire symbol of the source film, which Spielberg has raided and swamped in transgressive adulation.

Throughout Always, Spielberg and his writers tamper egregiously with scenes from A Guy Named Joe that worked adequately, adding a punched-up sound track and overwrought visuals. To cite but one example: in the original film's climax, Dunne steals the plane Van Johnson was supposed to pilot in a solo suicide mission, and bombs a Japanese ammunition dump, aided by the ghostly Tracy. The special effects in the sequence are modestly spectacular, thoroughly in style for a war film of the time. As Dunne returns to home base, Tracy speaks eloquently of the wonderful life waiting for her. She lands, and Tracy bids her good-bye.

Spielberg has Hunter steal the plane to extinguish a blaze that has trapped a platoon of smoke jumpers in a hard-to-reach mountain site. The pyrotechnics and acoustics of Hunter's overflight rival Luke Skywalker's run at the Deathstar. Afterward, Dreyfuss gives the Tracy farewell speech, virtually unchanged. The plane then stalls, crashes into the water and sinks like a stone. Hunter, in extremis and goggle-eyed, momentarily sees Dreyfuss. He pulls her to the surface, a few feet from the runway where her new lover is waiting. She walks toward him, Dreyfuss bids her good-bye, end of story.

Spielberg obviously must have believed these hyperbolic, clumsy changes (of which making Dreyfuss visible is the most risible, the latent rendered absurdly blatant) were artistically justifiable, satisfying elaborations. But inflicting them upon the yeoman work of the original appears as questionable as the enterprise of the Yiddish theater entrepreneur who earlier in the century advertised his company's production of Hamlet as a "shoyshpil fun Vilyam Shekspir—farendert un farbesert "—drama by Shakespeare, changed and improved.[11] One cannot know if the impresario was only repeating a hoary theatrical precedent: convincing himself he was after all only doing for Shakespeare what he believed Shakespeare had accomplished for Hollingshead.

The central issue for the purposes of this discussion is not the merits of Always relative to A Guy Named Joe; rather, it is the extraordinary merit the latter has "always" held for Steven Spielberg, along with the attendant possibility that an unconscious, oedipally driven competitiveness comprises the dark side of Spielberg's intense admiration for the original and its director. Some evidence can be adduced on this score from several anecdotes in Spielberg's biography.

The senior Spielberg has a background in electrical engineering, and he helped design early computer technology. He comes across as a pragmatic, hard-driving individual intensely passionate about scientific prog-

ress, equally passionate about conveying the wonders of the universe to an impressionable and admiring youngster: "With Dad everything was precision, accuracy. . . . He had the fastest slide rule in Arizona and spoke two languages: English and Computer. When I was a five-year-old kid in New Jersey . . . my dad woke me up in the middle of the night and rushed me into our car in my night clothes. . . . He had a thermos of coffee and had brought blankets, and we drove for about half an hour. We finally pulled over to the side of the road, and there were a couple hundred people, lying on their backs in the middle of the night, looking up at the sky. My dad found a place, spread the blanket out, and we both lay down. . . . He pointed to the sky, and there was a magnificent meteor shower . . ." (Margolis and Modderno, 102). This potent memory would later form the organizing stimulus for Close Encounters of the Third Kind .

Spielberg's first filmmaking experience involved emulation of, and competition with, his father: "A long, long time ago, I became interested in movie-making simply because my father had an eight-millimeter movie camera, which he used to log the family history. I would sit and watch the home movies and criticize the shaky camera movements and bad exposures until my father finally got fed up and told me to take over. I became the family photographer and logged all our trips" (Margolis and Modderno, 142, 144).

It would not be untoward to suggest that Spielberg's father thus inadvertently launched his son's career. Another episode speaks more pointedly to youthful rivalrous feelings. When Spielberg was eleven, his father came home and gathered the family in the kitchen: "He held up a tiny little transistor he had brought home and said: 'This is the future.' I took the transistor from his hand. . . . And I swallowed it. Dad laughed, then he didn't laugh; it got very tense. It was like the confrontation scene between Raymond Massey and James Dean in East of Eden . One of those moments when two worlds from diametrically opposite positions in the universe collide. It was as if I was saying, 'That's your future, but it doesn't have to be mine'" (Spielberg 62).

Spielberg's quotation from East of Eden is illuminating. In the movie, James Dean gives a classic performance as Cal Trask, a rebellious late adolescent desperately struggling to overcome his father's perennial displeasure, while wrestling with his own formidable ambivalence. The father is a stern, religious farmer who, like Spielberg's parent, worships scientific progress. He sustains massive losses in an ill-advised effort to send iced-down vegetables cross-country by rail. The scene Spielberg alludes to occurs after the father refuses to accept the gift of "dirty" money Cal made in crop-futures speculation during World War I. One notes that Cal's "tainted" agricultural enterprise was a spectacular success, whereas the father's failed abysmally, albeit "honorably," from the latter's censorious viewpoint.

Steinbeck's novel and the film derived from it are elsewhere singularly rich in oedipal resonances. Cal competes keenly with his brother Aaron for the father's love, as well as for Adam's fiancée. He seeks out his mother, a promiscuous hellion disowned by the father, now turned brothel owner, borrows money for his agricultural ventures from her, and later exposes her to Aaron after his father's rejection. Aaron's "good" persona obviously prefigures the preternaturally upright, idolized envied/resented paternal imago for Cal.

One may wonder if Spielberg discovered an analogous idealized father-rival in Victor Fleming. The leitmotif of A Guy Named Joe is the struggle in its hero's heart with another aviator over the same love object. Did a similar competition exist in Spielberg's psyche with Fleming, "possession" of the original film its aim, anxiety upon the prospect of fulfilling that aim inevitable?

From this perspective, Pete's "accidental" flooding of the town in Dorinda's tale takes on the ambiguous valence of a Freudian slip, where conflicted motive lies concealed beneath a gratuitous facade. Pete's surprising incompetence may be construed as a mask for Spielberg's ambivalent designs on A Guy Named Joe and its creator. It may be speculated that the director aimed consciously to "hit the target," that is, exhibit appropriate obeisance toward Fleming and his work, but could not resist indulging in a species of cinematic overkill and went considerably wide of the mark.

No proof should be drawn from the above that Spielberg is particularly "neurotic." One speaks here only to the presence—and possible influence—of unconscious conflictual residues in the director's films. On the evidence of biographical material as well as his own brief autobiography, he seems an engaging, assertive individual, who has labored exceptionally well under the stresses of his idiosyncratic craft, devoted to family and friends off the job.[12]

Setting aside the incidents previously described, there seems to have been little overt serious conflict between Spielberg and his father. He speaks of him consistently with affection and evidently remained close to him following his parents' divorce in his mid-teens. Spielberg has spoken of his mother with equal approval and not a little awe: "She had more energy than a hundred mothers her age. The image I have of her is of this tiny woman climbing to the top of a mountain, standing there with her arms out and spinning around. My mom was always like a little girl, who never grew out of her pinafore. . . . [S]he left a large wake" (Spielberg, 62).

While somewhat estranged from peers during late childhood and adolescence—accounts of the nature, degree, and hurtfulness of his alienation vary considerably from one report to the next—Spielberg indicates that life at home was generally happy. The temperamental differences between his parents did cause him distress, related by the director with characteristic

boyish diffidence: "My mom and dad were so different. That's probably why they were attracted to each other. They both love classical music . . . [but] aside from that, they had nothing in common. . . . My mother was a classical pianist. She would have chamber concerts with her musician friends, in the living room, while in another room my father would be conferring with nine or ten other men in the business about how to build a computerized mousetrap. These opposite lifestyles would give me circuit overload. My tweeters would burn out and my only insulation would be my bedroom door[,] which remained closed for most of my life. I had to put towels under the jamb so I couldn't hear the classical music and the computer logic. . . ." (Spielberg, 62).

Spielberg's account could have been drawn from the pages of a Thomas Mann novel. He depicts himself as a suburban Tonio Kroger, his identifications riven between an artistically inclined, emotive mother and a burgher-like father firmly anchored in scientific and business reality.

It can be reasonably argued on the basis of available sources that the director emerged from the oedipal vicissitudes of early childhood with balanced, loving perceptions of his father—indeed of both parents. Against this favorable background, with further unstinting parental affection he was able to weather the internal turmoil and external stresses of his adolescence. Drawing upon his native creative endowment, he eventually forged a primary identification with his mother's artistic inclinations, but also internalized his father's scientific interests and business acumen. The result is the adult of today: an auteur-producer-entrepreneur extraordinaire, exceptionally skillful at Hollywood's intricate business and passionate in advancing the technical parameters of filmmaking, whose eyes are fixed literally and figuratively upon the stars.

However even an immensely successful, stable son who enjoys a harmonious relationship with his parents may still harbor considerable unconscious fantasy referable to childhood traumata, including the oedipal struggle. When that son is an artist, such fantasies may fuel his art, successfully or quite otherwise. For instance, Spielberg has little to say about the impact of his parents' separation, but its signature is written poignantly across the characters of Elliot in E.T. and Carry Guffey's wonderful toddler in Close Encounters .

Both are children of divorce, each the apple of his mother's eye (like Spielberg), uncontested victor on the oedipal field—a contest no little boy really wants to win. Each bears the stigmata of paternal loss—loneliness and longing openly articulated by Elliot and wordlessly by the younger child in his delighted tropism toward the blinding presence on the other side of the door. Recuperation of the father's absence is accomplished for both in a relationship with alien voyagers, themselves condensations of omnipotent father and achingly vulnerable child.

Human paternal surrogates in these and other Spielberg films are frequently portrayed as impersonal authoritarian oppressors or benevolent facilitators. Alternately, positive and negative paternal images are condensed in a single character. In Close Encounters, the polarization is manifested on the one hand by the officers who attempt to thwart Roy Neary and his fellow visionaries from realizing their quest, and on the other by Lacombe, the luminously intelligent director of the secret mountain project whose intervention sends Neary across the galaxy.

In E.T., Keys, the leader of the team dispatched by the government to apprehend Elliot's "visitor," initially is presented as a cold, impersonal bureaucrat (Spielberg deliberately keeps him and his minions faceless in their early appearances). As the tale unfolds, Keys evolves into an increasingly sympathetic character. He can empathize with Elliot's neediness because of his own childhood yearning for an "E.T."

These divided representatives may be taken as embodiments of the child Spielberg's ambivalent perceptions of paternity—oedipally shaded, as-yet-unintegrated imagos of the powerful, beloved father who unveils the heavens to his adoring son, or the no less powerful, harsh authority figure who seeks to impose his iron will upon his resentful offspring. The negative side of the equation is further darkened by the specter of paternal abandonment, which appears to persistently haunt the director's imagination: abandonment through divorce in E.T. and Close Encounters (Spielberg's adolescent experience, projected backward upon those films' youngsters?), or through rank indifference in the case of Indiana Jones's work-obsessed father[13] and of the neglectful, fast-lane yuppie lawyer that a middle-aged Peter Pan has become in Hook (1992).[14]

I have noted in an earlier essay on Fellini that "the connection between the artist's triumphs or disasters in his creative life or his mundane affairs is incompletely understood at this stage of psychoanalytic theory" (Greenberg, 1975, 67). Pathobiography is an especially risky venture, often vitiated by dubious reportage, bias (including the myths artists spin around themselves), and scant clinical information. Freud himself acknowledged the limitations of interrogating Leonardo's oeuvre on the basis of a few historical details and a single, if trenchant, dream.

Acknowledging the fragmentary and inferential nature of supporting evidence, I submit that an oedipal gloss does offer modestly plausible grounds (internally plausible, that is, in terms of depth psychology) upon which to explicate the overreaching and excessive contrivance of Always . The only Spielberg film to treat heterosexual romance at length imbricates sexuality in a triangulation between two heroes and the woman they both love. The theme is common and ancient—and one that would seem to have proven particularly thorny for the director.

Other causes within and external to Spielberg's psyche life that may have

contributed to the film's aesthetic deficiencies must also be properly recognized: these include other directorial psychodynamics[15] and the dynamics of collaborators; financial and other "realistic" exigencies; and the creative limitations of other major or minor players in the production.

Setting aside Spielberg's specific difficulties in remaking A Guy Named Joe, it does not seem untoward to suggest that an intrinsic oedipal configuration lies deeply embedded in the remaking process, waiting to be evoked in the triangle between remaker, maker, and the original movie—the more troublesome to the degree that the source is perceived by its remaker as a mysterious, ultimately unavailable plenitude.[16] Barthes's remarks on the text as maternal object, and the oedipal thrust of narrativity seem apposite here:

The writer is someone who plays with his mother's body . . . in order to glorify [and] embellish it. (Barthes, 37)

Doesn't every narrative lead back to Oedipus? Isn't storytelling always a way of searching for one's original, speaking one's conflict with the Law, entering into the dialectic of tenderness and hatred? (Barthes, 47)

Pace other contributing factors, one speculates on the extent to which the shape (perhaps the quality as well) of remaking depends upon the project's oedipal significance for the remaker—notably, on how competitive strivings evoked by the maker and source are processed intrapsychically and artistically.[17] (An oedipal dynamic would clearly have greatest impact when a director or another personality under its sway exerts central influence over the remaking project.)[18]

Depth exploration of this issue lies beyond the scope of this inquiry, but several possible outcomes can be tentatively advanced for those cinematic "cases" where the original may have a significant oedipal meaning for the remaker:

1. The text exists under the sign of unwavering idealization; the remaker forswears competitive designs and remains unreflectively, even stultifyingly "faithful," to it.

2. The remaker, analogous to a creative resolution of childhood and adolescent oedipal conflict, eschews destructive competition with the maker, taking the original as a point of useful, relatively unconflicted departure.

3. The original, as signet of paternal potency and maternal unavailability-refusal, incites the remaker's unalloyed negativity. This precipitates a savage, contemptuous attack upon the original, in which its significant elements are erased, disfigured, and/or parodied.

4. The remaker, simultaneously worshipful and envious of the maker, enters into an ambiguous, anxiety-ridden struggle with a film he

both wishes to honor and eclipse. Caught up in contested homage, he eclipses his own native gifts—one ventures that this was the case with Spielberg in Always —dwindling to a hopelessly compromised raider of the lost text.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

Bloom, Harold. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Carroll, Noël. "The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond)." October 20 (spring 1982).

Dorfman, Ariel. "The Infantilizing of Culture." In American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives, edited by Donald Lazere. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988.

Druxman, Michael B. Make It Again, Sam: A Survey of Movie Remakes. New York: A. S. Barnes and Co., 1975.

Greenberg, Harvey R. "8 1/2: The Declensions of Silence." In The Movies on Your Mind: Film Classics on the Couch from to Frankenstein. New York: Saturday Review Press/E. P. Dutton, 1975.

———. "On the McMovie: Less Is Less at the Simplex." In Screen Memories: Hollywood Cinema on the Psychoanalytic Couch. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

———. "Spielberg on the Couch." Movieline, December 1992.

Holland, Norman N. "The 'Willing Suspension of Disbelief.'" In The Dynamics of Literary Response. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Jameson, Frederic. "Postmodernism and Consumer Society." In Postmodernism and its Discontents: Theories, Practices, edited by E. Ann Kaplan. New York: Verso, 1988.

Kael, Pauline. "Review of Always. " The New Yorker, 8 January 1990.

Luhr, William, and Peter Lehman. Returning to the Scene: Blake Edwards, Vol. 2. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1989.

Margolis, Herbert, and Craig Modderno. "Interview with Steven Spielberg." Penthouse, February 1978.

Menand, Louis. "Don't Think Twice: Why We Won't Miss the 1980s." The New Republic, 9 October 1989.

Mott, Donald R., and Cheryl McAllister Saunders. Steven Spielberg. Boston: Twayne, 1986.

Ray, Robert B. A Certain Tendency of the Hollywood Cinema, 1930–1980. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Smith, Dian G. "Steven Spielberg." In American Film Makers Today. Dorest, Mass.: Blandford Press, 1983.

Spielberg, Steven. "The Autobiography of Peter Pan." Time, 15 July 1985.

Steranho, Jim. "Behind the Camera: A Candid Conversation about the Past and Future Films of Steven Spielberg," Prevue (November 1981): 46.

Tallmer, Jerry. "Jawing with Steven Spielberg." The New York Post, Entertainment Section, 28 June, 1975.