Nineteen—

M*A*S*H Notes

Elisabeth Weis

When George S. Kaufman proclaimed that "satire is what closes on Saturday night," he was referring to its ephemeral quality: satire dates quickly. And I would add that political satire dates twice as quickly. Probably because the painful realities it mocks are all too immediate, political satire seems particularly funny while it is fresh. But the intensity of satiric humor is often inversely proportional to its durability. Try looking at the opening monologue from last year's Tonight Show . We don't even get the jokes. Or look at any reruns of Saturday Night Live that bash then-current presidents. For every political satire that remains funny, there are a dozen that could be called Saturday Night Dead .

If satire has a short life span, film is a medium that tends to date almost as quickly. While transcribing a screenplay to film, the camera also records such specifics as hair styles, acting styles, and even cinematographic styles, which permanently fix the film's production in a particular time and place. (Even in historical films, matters of style are kept within the parameters of contemporary fashion—to wit: the stars of M*A*S*H were allowed to wear their hair longer than allowed by military regulation for 1950.) By contrast, a play can be updated in performance, through acting style as well as language. Similarly, a novel is regularly transformed by the sensibility of each reader, who supplies much of the mise-en-scène with his or her imagination. But though films are certainly "read" by different viewers in different ways, there is a permanence to the original image that resists reinterpretation.

Hence, as both film and political satire, the 1970 M*A*S*H would seem particularly resistant to being remade. Robert Altman's send-up of the American involvement in Vietnam, the military mentality, and the estab-

lishment in general, is a movie particularly rooted in the counterculture spirit of its time.

But television is a greedy consumer. So many hours of broadcasting must be produced each day that it acquires properties rapaciously, adapting its varied sources according to its own needs. In a sense television is a gargantuan remaker of texts. It repackages anything from comic strip adventures to home videos for living room consumption. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that only two years after M*A*S*H became the third highest grossing feature film of 1970, the property was remade for television as a situation comedy. What is more surprising is the phenomenal longevity and popularity of a series based on a source that would seem to have offered few elements compatible with standard television practices.

The main reason M*A*S*H survived so long is that it underwent constant revision over its eleven seasons (1972–83). In an industry that values predictability, M*A*S*H evolved farther from its original form than any other series in television history. In that process it not only revitalized itself but adapted itself to a changing audience. While it never gave up its liberal outlook, the television show became more of a timeless comment on human behavior and less of an overtly political satire rooted in its time. I will discuss a number of factors that influenced M*A*S*H 's transformation over its 251 episodes, some of which are unique to M*A*S*H , and others of which follow patterns common to most long-running series. One could say that by constantly revising itself, the television series was per se a kind of ongoing remake. At any rate, if we are to study the translation of M*A*S*H from film to television, we must also study the continual evolution of the show, since there is a world of difference between the one-hour pilot and the final two-and-a-half-hour episode, a sentimental farewell wrap-up that attracted the largest audience in the history of television to that date.

M*A*S*H originated as a novel that Dr. Richard Hornberger wrote in 1968 under the name of Richard Hooker after serving as a thoracic surgeon in a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH unit) during the Korean War. The novel was bought for approximately one hundred thousand dollars. It was turned down by fifteen directors before Robert Altman agreed to direct it for Twentieth Century-Fox for a salary of twenty-five thousand dollars (Waters, 48).

The film was extremely popular with the public; it grossed $36.7 million at home (Knight, 82), and it became the first film ever to play twenty-four hours a day in London. It was also admired by industry professionals. It was the first American entry ever to win the Grand Prize at the Cannes International Film Festival and the first American film ever to win Best Picture from the National Society of Film Critics (which had previously favored such films as Blow-Up and Persona ). And the screenplay garnered an

Academy Award for Ring Lardner Jr., who had been blacklisted in the fifties.

The film's style was a revelation. It was the first theatrical film by Altman to manifest the elliptical cutting, the multilayered sound, the refusal to foreground a principal speaker, and the searching camera movements that we think of as the Altman aesthetic. Paradoxically, such a style demands viewer intelligence nearly completely at odds with the oversimplified politics of the film, in which all people are defined by their coolness and the virulence of their railing against establishment rules and regulations. To some extent, there is a connection between form and content: the film is anti-authoritarian, refusing on a stylistic level to assert total control over the viewer. (However, this assertion itself is oversimplified. The case has been made, for example, that Altman's zooms are very controlling [Karp, 25].)

While the film's aesthetic achievements remain impressive, its simplistic attitudes have dated it embarrassingly. Its politics, other than its diatribe against the absurdity of war, seem puerile. The surgeons who are its heroes express themselves in the mode of frat-party antics. Altman seems not only to condone but share their adolescent view of women. For instance, most of the nurses are introduced as they hike up their skirts to get out of a helicopter. Nor are the surgeons much more mature in their relationships with men. Hawkeye and Trapper have all the intolerance of youth: they are equally contemptuous of military martinets, bigots, incompetents, and anyone who believes in God. Those characters who are not hip or cool by the standards of the late sixties are fair targets for ridicule and humiliation. "Cool" could be epitomized by the fact that Hawkeye Pierce (Elliott Gould) has arrived with a jar of olives in his pocket to go with the martini proffered by Trapper John (Donald Sutherland). "Cruel" could be epitomized by the double exposures of Margaret Houlihan (Sally Kellerman) to the public. First, her lovemaking with a married doctor is broadcast over the camp loudspeaker for all to hear. This humiliation is presumably justified by her hypocrisy—her unwillingness to admit to her sexual desire. But then, in order to settle a bet about whether she is a natural blonde, the surgeons reveal her pub(l)ically as she showers. It is a measure of Altman's sensitivity to the situation that he allows the film viewers as well as the diegetical audience to witness her naked humiliation.

The film assumes counterculture values on the part of its audience that we associate with the late sixties. For instance, it exhibits a positive attitude toward drugs. The ubiquitous public address system makes a plea for audience complicity with its several references to stolen amphetamines or the fact of marijuana being declared an illegal substance. Drugs are agents of the good guys, tools for the surgeons in their nonmedical schemes. Hawkeye and Trapper use drugs to induce sleep in a dentist (in an elaborate scheme to persuade him that he is not impotent—or gay; the two seem

interchangeably undesirable). They use drugs to knock the opposition out of a crucial football game. And they use drugs to try to keep their Korean houseboy from being drafted.

If the film's irreverent and antiestablishment attitude made it a success with contemporary audiences, it does not retain its hold on the popular imagination today (to judge by a survey of rentals in video stores). By contrast the television show not only did well during its original decade but has kept its mystique in reruns, which consistently outdraw counterprogramming (Waters, 50). Variety regularly wrote articles tracing M*A*S*H as a unique phenomenon that in rerun could "attract and hold an audience at any time of the day" (e.g., Knight, 83).

How much of Altman's M*A*S*H was retained for television? The basic premise remains the need to act crazy in order to preserve one's sanity. The film's three cool surgeons are reduced to just Hawkeye and Trapper John. Duke, the third, who is exposed as a Southern bigot in the film, is eliminated. His bigotry is instead ascribed to the two-dimensional Major Frank Burns, who now is not only a pompous zealot, as in the film, but takes on every possible negative (read square) characteristic.

Of the cast, only Gary Burghoff, as Radar O'Reilly, the clairvoyant company clerk, was retained among the principals. (Two minor players had also been retained but were eliminated during the first season: G. Wood, as General Hammond and Timothy Brown as Spearchucker Jones, who was cut when it was learned that there had been no black surgeons in Korea.) However, the personality of the film's Radar had barely been developed. The television character is a cuddly, naive, kind-hearted kid who sleeps with a teddy bear and is hardly allowed to grow up during his seven years' tenure.

One production decision both preserved some of the free-flowing character of the film and allowed for more aesthetic expressiveness than had been seen before in a situation comedy: the decision to shoot not on tape with three simultaneous cameras but rather on film, using the one-camera system. A previously unheard-of rehearsal day was also scheduled before each shoot, a measure that added to the ensemble of the acting.

The film's gore in the operating room and irreverence toward authority are kept but toned down for living room reception. The caustic outlook is mellowed considerably. Perhaps typical of the softening is the treatment of the opening theme song, "Suicide Is Painless," which is retained but without the lyrics, which might offend delicate American sensibilities.

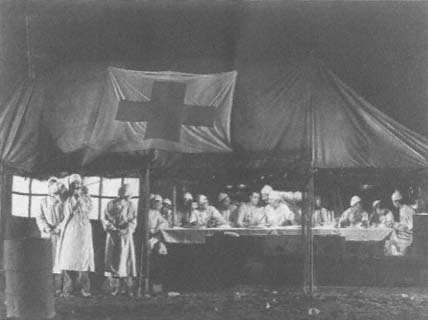

The two stills of eating scenes that accompany this article are meant to illustrate this shift in emphasis. The first is from the film's "Last Supper" scene, in which a dentist prepares to commit suicide as several bystanders serenade him with the "Suicide Is Painless" ballad. (See figure 39.) By contrast, the television still depicts what could be called Radar's First Supper after a tonsillectomy. In one of the last episodes before Radar leaves the

Figure 39.

The "Last Supper" scene in Robert Altman's M*A*S*H mixes parody

and irreverence in a knowing "wink" at the audience (1970).

show ("None Like It Hot," season seven), the doctors go to considerable trouble to get Radar (and themselves) his favorite flavor of ice cream. (See figure 40.) The Last Supper sequence, with its irreverent references to suicide and its religious iconography would have been as improbable on television as the strawberry ice cream episode would have been in the film, which has little appetite for sweetness.

In other words, though the television series adopted the characters, the situation, and the antiwar stance of the film, the values, and the tone shifted dramatically. To be sure, some character virtues remain consistent throughout the film and television versions; in both media the good guys are defined by: 1) their competence as doctors, 2) their tolerance toward the Other (usually a Korean peasant or a black soldier), and 3) their sense of humor. But as for personal style, there is almost a 180-degree reversal. The coolness of the movie surgeon heroes includes an emotional distance—from their own feelings as well as those of others. By contrast, the television episodes valorize those characters who are most sensitive and vulnerable. The change is gradual. It is already discernible in the difference between film and TV pilot. But for reasons I will discuss below, the shift occurs mainly during the latter half of the series.

Figure 40.

The M*A*S*H surgeons feed strawberry ice cream to Radar

after his tonsillectomy in the popular television series.

In short, the television producers of M*A*S*H were able not only to adapt the original movie to their needs but to reformulate the program over the years so as to emphasize character development. Because of the flexibility of the format the series maintained both its quality and its popularity. When it went off the air in 1983 it was the third-most-watched program—after 60 Minutes and Dallas . What creative, economic, and political factors enabled M*A*S*H to adapt and survive?

Network Policy

M*A*S*H was produced by Fox Television (it was standard practice in a film contract that television rights went to the studio that made a film). Its creators (I shall use the terms "creators" and "producers" interchangeably because nearly all of the principal personnel worked as producers, writers, and directors) brought it to CBS, which had just begun televising the two other most intelligent and revolutionary sitcoms of the seventies, All in the Family (1971–79) and The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970–77).

Though more open-minded than the other major networks, CBS still

had its rules. In his definitive study of television comedy, Comic Visions, David Marc cites a CBS market research study that concluded that the three kinds of characters Americans would not watch on sitcoms were women who were divorced, men who wore mustaches, and anyone from New York City (Marc, 167). In such a climate it is amazing what M*A*S*H got away with. One battle that M*A*S*H 's creative team did not win involved the laugh track. Despite the M*A*S*H producers' vigorous resistance to canned laughter, CBS retained it except in most of the operating room scenes. (However, the laugh track was mixed at a lower level than usual relative to the rest of the sound track.)

CBS clearly felt some ambivalence toward its new product. One measure of a network's support of a new program is its willingness to sustain low ratings to see if the program will catch hold. The network did agree (after sustained lobbying on the part of the show's creators) to continue the show for a second season despite the fact that M*A*S*H had finished in the bottom half of the prime-time ratings during its first season. However, CBS may have been responsible for M*A*S*H 's slow start in the first place: they had slotted it for viewing at 8:00 P.M. on Sundays, which was a "family hour" slot. But once the network executives did make a commitment to M*A*S*H for a second season, they gave it their best slot: 8:30 P.M. Saturday, between All in the Family and Mary Tyler Moore. M*A*S*H moved up to fourth place and stayed in the top twenty shows for a decade, despite being bounced around to eight different time slots.

Perhaps an indication of industrywide ambivalence toward the program was its results in the competition for Emmy Awards. M*A*S*H was nominated for a large number of Emmy Awards (ninety-nine) but won only fourteen, despite its reputation within the industry as one of the best shows on television. M*A*S*H producers have said that the relative paucity of these awards (it won many other awards based on audience popularity) reflected the inability of the industry to deal with something uncategorizable. M*A*S*H was pigeonholed as a sitcom. However, the producers' favorite episodes were often their most serious in tone, and it was these shows they submitted for nomination (Prelutsky, 19).

Genre Expectations

To some extent, genre expectations will militate against any radical change in a television series. From the start M*A*S*H did not fit into the genres of its closest predecessors, the service comedy or the doctor series. It was indeed a situation comedy, but as I have just suggested, eventually M*A*S*H remade itself into a genre unique on television. In an industry that banks

on reliability and predictability, M*A*S* H confounded expectations. Although the series never entirely dropped its dependence on silly sitcom plot devices (e.g., convincing Frank that there is gold to be found in the local hills—"Major Fred C. Dobbs," season one), M*A*S*H was what its creators called a "dramedy" (in a documentary called "Making M*A*S*H "). Its creators had insisted that the war not serve just as a background for high jinks (as a Nazi POW camp had for Hogan's Heroes ). During the first season they battled with CBS over one episode in particular ("Sometimes You Hear the Bullet") in which a sympathetic character, an old friend of Hawkeye, dies on the operating table. When the episode aired it became clear that the audience would accept a mixture of reality and comedy previously unheard of on a television sitcom. As recently as 1967 Bonnie and Clyde had caused a critical uproar with its mixture of comedy and violence. Its popularity with movie-theater audiences may have helped pave the way for American audiences to accept a mixed genre on television.

Popularity

Thus the contract with the audience that usually obtains with sitcoms and other genres was allowed to be modified. It was Alda's belief that once the program gained its viewers' trust and affection, the show could then deviate from rigid expectations: "The audience made a pact with us. We could be as imaginative and exploratory as we wanted . . . because they knew we would never be wanton with them" (Corliss, 65). As the program became a hit, this popularity gained for its producers unprecedented freedom from the network as well as the audience (which was light-years ahead of the network executives). According to Larry Gelbart, "As our ratings climbed, corporate resistance fell. . . . I am convinced that we achieved a creative freedom unheard of in the medium before or since" (Gelbart, 25). The program was equally popular with young and old, men and women (Dougherty, 8). Besides being well written, well acted, and funny, it evidently had something for everyone in the audience, including farce and feeling, buffoonery and literary allusions. The character of Radar, for example, was designed for his appeal to children and older women.

Thus, the audience's loyal acceptance of whatever M*A*S*H dished out allowed changes of tone; it became possible to drop completely any pretense of being a comedy for all or part of some episodes. The show's creators also experimented with formal innovations. As often as not, the structure abandoned the classical sitcom formula in which the "situation" is disturbed but the order is resolved within twenty-four minutes. Indeed, there are any number of episodes that have no plot at all. One frequent substitute format

is the "letter home" (written by any of the principals, or even a visiting shrink) in which a voice-over provides some narrative structure.

Another episode ("Hawkeye," season four) consists solely of a monologue, in which Pierce, who has sustained a head wound, keeps talking to a family of noncomprehending Koreans so as not to lose consciousness. (This episode is one of the few that were allowed to be aired without a laugh track.) The elegance of this episode is that it takes to an extreme one of Hawkeye's best-known tendencies: volubility. His character has a wisecrack for every occasion, a love of wordplay and alliteration, and a tendency to deliver orations on any occasion (hence the ode to the thumb in "Hawkeye" or the ode to the "tushie" in "Dear Ma" [season four]).

Perhaps the most acclaimed episode is "The Interview," an episode shot in black and white in which the characters are interviewed as if for a stateside newsreel. Although the writers made a number of suggestions, much of this episode was improvised by the actors, who by this time (season four) had become greatly involved with the development of their characters.

Another deviation from convention was the "Dreams" episode (season eight), which ventures into surrealistic representations of the characters' anxieties as they take cat-naps during an operating marathon.

If the above experiments delve into the feelings of the medics, several other experiments emphasize the ordeals of the patients. "Point of View" (year seven) is filmed entirely from the literal perspective of a wounded soldier who cannot talk. "Life Time" (season eight) superimposes a clock on bottom right of the image as we go through the twenty-four minute rescue with a wounded soldier who risks paralysis if surgery isn't undergone within twenty minutes.

Writers and Creative Personnel

All told, the series had seventeen regular writers in addition to any number of freelancers. But one can reasonably divide the series roughly into two eras that match the sensibilities of the two men who perhaps exerted the greatest creative influence: Larry Gelbart, who wrote ninety-seven episodes (and produced and directed many others), and Alan Alda, who wrote and directed over forty episodes.

Larry Gelbart, who was brought in to write the pilot and who stayed for four seasons, was considered the most brilliant writer in the industry (Knight, 83). He has written for television (including Your Show of Shows ), Broadway (including A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and the recent City of Angels ), and film (including Tootsie ). Judging from the episodes on which he is given writing credit, his imprint on M*A*S*H includes: 1) hilarity (he was by consensus the funniest writer the show ever had

[Swerdlow, 6]), 2) a love of formal experimentation, 3) a political edge, and 4) a tendency to prefer sketch formats to dramatic unity.

The departure of Gelbart after four seasons was one of the catalysts for changing the show's sensibility. According to producer (and, often, writer) Gene Reynolds, "The tone of the comedy had to change when Larry left, because we just couldn't equal his comic genius. We were forced to explore other areas, areas that he had not had to bother with, because he was so gifted, so skillful in straight comedy" (Reiss, 116).

Gelbart always said that the character who represented his values and mind-set was Hawkeye. By the time Gelbart left the show, Hawkeye was universally considered the heart of the series. By this time the distinction between the personas of Hawkeye and Alan Alda was getting blurred. Alda was as much a galvanizing force behind the scenes as his Hawkeye was on screen (Waters, 48). Not surprisingly Alda's writing contributions as well as his conscious and unconscious identification with the character he played tended to make Hawkeye both more sensitive and more complex.

Over the years Hawkeye becomes less of a drinker and womanizer and more actively compassionate. His greater sensitivity (as well as the increased introspection of the other characters) was generally attributed to Alda's own self-image. Indeed, as David Marc suggests, "Psychological introspection established itself as M*A*S*H 's primary text during the late seventies" (199).

Although it would be impossible to prove the direct links between Alda the person and Alda the writer, one can infer a certain amount from interviews and credits. In 1974 he told the New York Times, "All we're attempting is to deal with reality with a sense of humor, to find the fun of behavior and character. I think that's where the best of TV is moving—humor with feeling. . . . To me, only the things that really count are funny, not those old earthshaking questions like should sonny boy tell dad he bent a fender on the family car" (Berkvist, 19). Episodes that appear to reflect Alda's sensibility tend toward: 1) introspection, 2) valuing vulnerability as a character trait, 3) sanctimoniousness, and 4) formal experimentation. Alda's activism as a feminist and his love of pranks also seem to have permeated the show.

Despite individual sensibilities, producers, writers, and performers were apparently pretty much in sync; they were united against a common enemy. Their frustration at having to fight the networks was transposed via the scripts into annoyance with army intransigence. Gelbart once wrote that "[a]lthough turning out a mini-movie on a three-day shooting schedule . . ., battling compromise and complacency all the way, is not of course, in any sense as dangerous or serious as risking one's life in combat, the pressures of making the series gave those of us responsible for it something of the sense of madness, the feelings of frustration and fatigue shared by the surgeons and nurses of the 4077th " (Gelbart, 26). So, for example,

when the network censors made the writers remove the word "virgin" from the dialogue, they mischievously introduced a solider in the next episode from the Virgin Islands (Kalter, 29). This petty kind of reprisal is typical of the rebellion against authority that takes place within the plot.

Subject Material

In 1974 Gelbart and Reynolds had gone to Korea, visited the MASH unit that inspired Hornberger's book, and interviewed about 150 doctors who had served in frontline hospitals (Darrach, 102). They claimed to have interviewed there and later at home nearly every doctor who was in Korea. Reynolds estimated that these stories formed the basis of some 60 percent of the episodes dealing with military or medical incidents (Corliss, 65). Eventually this source of inspiration had to dry up.

Thus, the combat-hospital situation per se had been exhausted as a source of humor. Gelbart said he left the show at the point when he could no longer come up with new story lines. Considering how long the show had been running, and how few chances there were to expand the characters' experiences (given their restricted lives on the military base), the easiest way to expand the material was to deepen the characters.

And so M*A*S*H became increasingly a comedy of character. Linked to this shift of emphasis from situation to character comedy was the emphasis on probing psyches. Conveniently, the two actors (Larry Linville and McLean Stevenson) who played types least capable of changing left the show. These two-dimensional doctors were replaced by characters who were not as silly but were more complex. Most of the remaining principal characters were allowed to evolve. For instance, Corporal Klinger eventually gives up trying to get out of the army on a "Section Eight" by wearing women's clothes.

The greatest change is on the part of the head nurse, Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan. Her gradual transition from sex object-martinet to sympathetic woman can be traced through a series of critical episodes. Her first treatment as a human being occurs in season two ("Hot Lips and Empty Arms"), which was written by Linda Bloodworth and Mary Kay Place. Her loneliness and vulnerability are explored in "The Nurses" (season five—also written by Bloodworth). Seasons five and six see Major Houlihan through big changes. She gives up Frank and gets engaged, married, and divorced by season seven and is allowed to grow from her pain. "Hot Lips" is by now called "Margaret" and is treated with respect.

The most striking episode in this regard is "Comrades in Arms" (written by Alda, season six), where Houlihan and Hawkeye, trapped and terrified

by gunfire, make love. Although they do not continue the affair after that night, they are no longer antagonists. Indeed, toward the end of the series' run, the only way to introduce antagonists into the script was to import personnel (like the paranoid Colonel Flagg) from off base.

Influence of the Actors

On a long-running series there is inevitably a push from serious actors to get meaty parts—to expand their characters' emotional range. On the M*A*S*H set, push did not come to shove. Script development was a matter of ongoing collaboration between writers and players. In addition, most of the principals wrote and directed some episodes.

A second way in which actors influenced the show was unwitting: the writers often wrote the actors' pastimes or behavioral tics into their parts. Hence, David Ogden Stiers's love of classical music is a defining characteristic of Major Winchester. After Loretta Swit took up yoga, Margaret can be found practicing it on-screen. Hunnicut uses his real daughter's real name in referring to B. J.'s baby. Alda wrote and directed an episode "Inga" (season seven) in which he admittedly explored his feelings of being threatened by smart women.

After battles with the military were played down as plot devices and human relationships were emphasized, the group dynamics of the cast was sometimes introduced into the scripts. Thus, when the writers noticed that Gary Burghoff and Loretta Swit were treating veteran actor Harry Morgan as a father figure, they wrote that relationship explicitly into the script for the same actors (Darrach, 103). Of course, there was not always a correspondence between life and art. Gary Burghoff, however cuddly as Radar on-screen, did not fit into the congenial atmosphere of the set (Prelutsky, 21).

Yet another parallel between life and the show was the use of elaborate practical jokes to relieve the arduousness of fourteen-hour days on cramped or cold sets (Kalter, 179). And episodes depicting the departure of characters like the original commander, Henry Blake, were evidently full of genuine tears as the actors played their farewell scenes.

But probably the most extreme case of personal dynamics influencing the direction of the series was the fact that the writers became personally much closer to Alan Alda than to Wayne Rogers. Originally Trapper John and Hawkeye were supposed to have had equally developed parts. But as the writers drew closer to Alda, they developed his role more fully. Wayne Rogers finally got so frustrated at playing second fiddle that he sued the company and left (Swerdlow, 6).

Replacement of Cast Members

Until M*A*S*H, industry wisdom had had it that you could not successfully replace more than one principal on a sitcom. Yet M*A*S*H replaced three principal cast members. In each case the replacements portrayed more rounded characters. Two transitions occurred at the end of the third season with the departures of Wayne Rogers and McLean Stevenson.

The trade-in of Wayne Rogers's Trapper John for Mike Farrell's B. J. Hunnicut was a shift from a more caustic character to a sweeter guy—one could say from Wayne Rogers to Mister Rogers (B. J.'s overriding attribute is his longing for his family). For the most part, Trapper is a boyish prankster, a drinker, and a womanizer, in short, the character most resembling the doctors in Altman's film. However, as early as the second season, Trapper John is allowed to serve as the center of an episode ("Kim"), when he becomes fond of an abandoned Korean boy who has been found by the MASH outfit. Shortly after he gets his wife's permission to adopt the boy, the child is discovered standing in the middle of an American minefield. The show suddenly shifts from tenderness to tension as Trapper risks his life (metaphorically, love is a minefield!) to rescue the boy. It is useful to compare this episode with "B. J. Papa San" (season seven), in which B. J. becomes a surrogate father to a local Korean family. Whereas the earlier story is played mostly for suspense, the latter story emphasizes the psychology behind B. J.'s behavior.

Oddly enough, the Trapper character got to evolve offscreen. In 1979 a new Trapper, played by Pernell Roberts, reappeared as an older and wiser figure starring in his own spin-off (Trapper John, M.D. ) This avuncular incarnation of Trapper was chief of staff at a San Francisco hospital, where his wisdom was counterpointed by an idealistic but impatient younger surgeon.

The end of M*A*S*H 's third season also saw the departure of McLean Stevenson, who portrayed Henry Blake, a commander whose heart is in the right place but whose mind and body are always several steps behind. He remains a shallow figure whose goofiness in all respects except medicine is visualized by an ever-present cap bestrewn with fishing lures. Henry Blake is not really treated as a serious character until his offscreen death. "Abyssinia, Henry" ends with the announcement that on his way home his plane has been shot down.

Stevenson was replaced by Harry Morgan, who plays Colonel Potter, a career army (former cavalry) colonel whose quaintness is defined by the number of ways in which he can refer to horse dung. Potter's arrival marks a pronounced shift in tone, as he is the first regular army character who is also a regular guy.

Finally, at the beginning of the sixth season there was a change in the

chief antagonist. Frank Burns (Larry Linville) had been a cartoon figure with no redeeming qualities. Stories involving Burns come the closest to traditional witless sitcom. The typical M*A*S*H episode interwove three plots, with the Frank Burns plot nearly always providing broad comic relief and visual slapstick even if the other two plots were more serious. As an inhuman and inhumane character Burns was an easy target. He was replaced by a character inspired by William F. Buckley (Kalter, 117), the pompous Charles Emerson Winchester III, played by David Ogden Stiers. Winchester has the usual obsessiveness of a comic figure (his snobbishness) but is allowed to be a good doctor and a worthy opponent to the prank-loving Hawkeye. Winchester is also allowed to have occasional moments of generosity and compassion. While there is no doubt that the shift from Frank to Charles resulted in fewer laughs, I happen to greatly prefer the latter. It is a shift from slapstick to wit as a means of battle.

Thus virtually all the replacements of characters in M*A*S*H also precipitated a change in type of comedy. The switch from Burns to Winchester was from slapstick to wit; from Colonel Blake to Colonel Potter was from laughing at the former's incompetence to sharing the latter's sardonic sense of humor. And the replacement of Trapper by Hunnicut brought a transition from malicious to gentle humor.

Changes in the Political Climate

M*A*S*H 's producers met more resistance from the network to its handling issues like adultery and homosexuality than to its antiwar stance. One can make the case, as the producers did, that M*A*S*H was neither about Korea nor Vietnam but about the absurdities of the military mentality and all war—especially in regard to the futility of sewing up wounded soldiers so that they could be sent back to the front. Nevertheless, many of the points about the war take particular advantage of the parallels between the situations in Korea and Vietnam. For instance, "Yessir, That's Our Baby" (season eight) raises the problems of Amerasian babies fathered by Western soldiers and left with their Korean mothers, who find their children are outcasts.

The series never lets the viewer forget for long that the war is being fought on the homes and farms of innocent peasant families. Koreans are portrayed most often as orphans, wives, or dispossessed farmers. In addition, some of the episodes deal with issues of cultural difference as Frank regularly misinterprets local customs. Indeed, characters can be measured by their sensitivity to local people. Radar is the only principal who speaks Korean. In the final episode, Corporal Klinger marries a Korean woman.

It is hard to gauge to what extent the series anticipated or reflected the public's growing disenchantment with the fighting in Vietnam. Undoubt-

edly, the references to pointless slaughter in the Far East lost some of their edge after season five, when Vietnam was no longer a front-page story.

As the nation's interests turned inward, so did the show. The tendency toward introspection of the main characters paralleled the increased self-examination and narcissism of the early eighties. As Newsweek put it, "With a canny eye on a new generation of viewers, the series stepped off its leftist, issue-oriented, anti-establishment platform and took on the introspective tone of the Me Decade" (Waters, 50).

One certain parallel between the series and the national psyche was the heightened sensitivity to women's issues. Early episodes regularly exploit the nurses as convenient sex objects. In "Radar's Report" (season two), Hawkeye falls for and proposes to a nurse who then rejects him because she just isn't interested in marriage. However, this is still a story about Hawkeye's feelings, and the nurse's point of view is not examined.

Eventually, homebodies B. J. and Colonel Potter replace womanizers Trapper John and Henry Blake, and Hawkeye stops his inveterate skirt chasing. Perhaps the most direct lecture on feminist pride comes when Nurse Kelly, played by Kellye Nakahara, a regular irregular on the series, is finally foregrounded long enough to proclaim with conviction that she is adorable despite her unglamorous appearance.

Iconization of the Characters

Because M*A*S*H revealed so many facets of its principals' personalities, it followed that the audience would feel more attached to them than to most television characters. It also followed that this attachment would adhere to the actors playing them as well. In 1980, a Ladies Home Journal survey found that Alan Alda was tied with Sally Field (who was playing a flying nun) as the most trusted personality on television (White, 27). In 1983, the last year of the series, Alda had the highest male TVQ (popularity rating) in the country (Romano, 12-I). Clearly this is a case of viewers confusing characters with the actors who play them. The audience's affection extended to the cast as a whole. In the late 1980s, IBM capitalized on nostalgia for the cast when it reassembled most of the M*A*S*H stars in a series of computer commercials. The status of the M*A*S*H compound as a national treasure was acknowledged when the Smithsonian placed parts of its sets on exhibition.

Sentimentality for the series was paralleled by sentimentality within the scripts. As M*A*S*H shifted from satire to character exploration, its tone shifted from hard-edged liberalism to sentimental liberalism. The final, two-and-a-half-hour episode was an unabashed tear bath. To some extent the series may well have been responding to the political climate in the

country as a whole. That is, the growing sentimentality of M*A*S*H may mirror the change in the national psyche from post-Watergate cynicism to Reagan-era soft-headedness.

But I suggest that the sentimentalization would have happened in any era. Alda-Hawkeye had become a national treasure. And when a serialized cultural icon becomes a national treasure it goes soft.

To wit: Mickey Mouse, originally a bit of a dirty old mouse (see "Plane Crazy," 1928), became as clean as a cub scout as his popularity rose. Thereupon the Disney company created Donald Duck to play antagonist in the thirties (see "The Band Concert," 1935). Soon Donald mellowed and acquired three cute nephews plus a new antagonist, his Uncle Scrooge. On television Archie Bunker remained a bigot in later years, but he too mellowed considerably by the time All in the Family became Archie's Place . At the end of Murphy Brown 's 1991–92 season, that feisty, female curmudgeon became a single mother. Dan Quayle turned her into an instant icon for the poverty of family values. But what we actually saw in the final episode was a touching endorsement of motherhood—Murphy croons "You make me feel like a natural woman" as a lullaby to her newborn son.

With Murphy as a mother, the show has vacillated between political cynicism and domestic sentimentality. Murphy has indeed become a character very much in the mold of Alda's Hawkeye Pierce. Perhaps the reason both characters (and therefore their shows) have touched something in the American psyche is that they each created a persona that many viewers like to think is their self-image: the tough but tender American, who just happens to have better writers than we do.

Thanks to Lucy Fischer, Krin Gabbard, and Andy Horton for reading the manuscript for this essay and making helpful suggestions.

Works Cited

Berkvist, Robert. "M*A*S*H Is His Passion." New York Times, May 19, 1974, sec. 2, p. 19.

Cooke, Alistair. M*A*S*H Was One of a Kind." TV Guide, February 12, 1983, 14–21.

Corliss, Richard. "M*A*S*H, You Were a SM*A*S*H." Time, February 28, 1983, 64–66.

Darrach, Brad, with Suzanne Adelson. "M*A*S*H. " People, March 7, 1983, 100–103.

Dougherty, Philip H. "Advertising: Hot-Selling M*A*S*H Air Spots," New York Times, February 28, 1983, p. D8.

Gelbart, Larry. "Its Creator Says Hail and Farewell to M*A*S*H, " New York Times, February 27, 1983, pp. B25–26.

Henry, William A. III. "M*A*S*H. " Horizon, September 1978, 84–87.

Kalter, Suzy. The Complete Book of M*A*S*H. New York: Harry Abrams, 1984.

Karp, Alan. The Films of Robert Altman. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1981.

Knight, Bob. "Something Clearly Out of the Ordinary." Variety, February 23, 1983, 82, 88.

McFadden, Robert. "M*A*S*H Farewells Mix Fun and Nostalgia." New York Times, March 1, 1983, pp. B1, 4.

Marc, David. Comic Visions: Television Comedy and American Culture. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989.

Prelutsky, Burt. "The Troops Scatter—but the Memories Linger." TV Guide, February 12, 1983, 18–21.

Reiss, David. M*A*S*H. New York: Macmillan, 1983.

Romano, Carlin. "Mustering Out with M*A*S*H ." Philadelphia Inquirer, February 27, 1983, p. 12–I.

Swerdlow, Joel. "The Staggering Success Story of those Zany Cut-Ups from the 4077." Washington Post, April 27, 1980, p. M6.

Waters, Harry F., with George Hackett. "Farewell to the M*A*S*H Gang." Newsweek, February 28, 1983, 44–50.

White, Diane. "M*A*S*H Is More Than a Laugh Track." Dial, January 1981, 26–27.