Eighteen—

"Tonight Your Director Is John Ford":

The Strange Journey of Stagecoach from Screen to Radio

Peter Lehman

Like many commentators on John Ford's Stagecoach , Edward Buscombe observes that the journey undertaken by the coach does not conform to the narrative implication that the travelers are going west into Indian[1] country. If the fictional journey has a strange geographical dimension to it, that is not the only strange journey that this fictional coach would undertake. On January 9, 1949, the NBC Theatre debuted with a half hour radio version of John Ford's Stagecoach. NBC Theatre was renamed Screen Directors Playhouse and, in 1950, expanded to one hour; it ran until 1951 (Dunning). It featured adaptations of successful films with many of the original stars. The films' directors introduced the programs and chatted about the original film afterward. A version of Fort Apache , which was broadcast on August 5, 1949, was the only other Ford film to be included in the series.

Since the shift from film to radio involves a form of adaptation, why consider it in a volume devoted to remakes? Actually, radio adaptations differ significantly from literary adaptations, which are generally the focus of adaptation studies. The author of the original literary work frequently has no creative involvement with the film adaptation and, in the case of many of the most prestigious adaptations, has lived before cinema was even invented. The mere fact that film adaptations included works by Shakespeare, Emily Brontë, and Tennyson created a significant distance between the original creators and the creators of the adaptations. Even when a living author has a role in writing the screenplay for an adaptation, as for example Mario Puzo did with The Godfather , such involvement at most seems to imply a likelihood that the adaptation will somehow be more faithful to the original vision of the novel. Such participation is not, however, directly perceived by the film spectator.

The Screen Directors Playhouse involved as many of the original stars as

possible re-creating their roles. In Stagecoach , both John Wayne and Claire Trevor play the same characters they played in the film and, similarly, Henry Fonda and John Wayne play the same central characters in both the film and radio versions of Fort Apache . Thus, the radio listener hears the same actor that he or she may have heard in the film, at times even speaking the exact same lines. In some sense, then, there is a more direct remake element at work in the radio programs, if only insofar as the fact that well-known actors are re-creating parts for which they are already famous. This points to yet another significant difference between filmic adaptations of literary works and radio adaptations of films. In the former case, many of the film spectators would not have read the original novels, plays, or poems or, if they had, they might have done so long ago. The Screen Directors Playhouse , however, featured recent popular films that many of the radio listeners would have seen. Although it included classics from the early forties such as Stagecoach , the 1949 broadcast of the 1947 film Fort Apache is much more typical of the series, and some of the programs even featured current films.

Since Stagecoach was the first program in the series, the introduction by George Marshall, president of the Screen Directors Guild, included comments about the nature of the new program "in which the directors will personally bring you their favorite film assignments." "Tonight," he tells the listening audience, "your director is John Ford." At the program's conclusion, Marshall returns, "Speaking for the Guild I'd like to express our gratitude to the National Broadcasting Company for the opportunity to better acquaint the public with the work and role of the screen director." Marshall's comments imply a close relationship between the original film and the radio version. Indeed, the public will not only become acquainted with the director who will "personally" introduce the film but also with the function of the film director. Although faithfulness to the original had long been a critical concept applied to film adaptations of novels, such adaptations were generally presumed neither to "personally" acquaint the filmgoer with the novelist nor to educate the film viewer about the role of the author. Even if it was presumed that one might learn about the original novel from such films, it was not presumed that one learned about writing fiction. During the discussion with Ford, Wayne, Trevor, and Ward Bond concluding the program, Trevor reinforces Marshall's point by remarking, "You know, I think it's wonderful that the screen director is being honored like this. He's the fellow that really makes the movie. Ask us actors and actresses."

The Screen Directors Playhouse is caught within a bizarre paradox. Sponsored by the Screen Directors Guild, it seeks to promote both the original film and the role of the director in creating that film, but it does so within a medium singularly unsuited to showcasing the talents of a film director. The announcer foregrounds this paradox at the beginning of the program, "Screen Directors Guild Assignment; production: Stagecoach ; director: John

Ford; stars: John Wayne, Claire Trevor, Ward Bond." After a brief musical interlude, another announcer repeats the film title and actors and adds, "And introducing the director of the film, John Ford." Initially, it sounds as if Ford is the director of this production since he is listed with the stars (one of whom, Ward Bond, was not even in the film version). Moments later, however, we hear the ambivalent announcement that this production will be "introducing" the film's director, John Ford. What then is his role in this production? At the conclusion of the program, the announcer tells us, "Production was under the supervision of Howard Wiley." It sounds at first like Ford is the director of this production, then like he is being introduced to the radio audience in his capacity as the film's director, and finally it becomes clear that he has had no role in this production other than that of brief guest.

This is a strange way either to acquaint the public with the role of the screen director or to honor "him," since, as I will argue, no significant features of the original aesthetic text survive this cross-media remake. Indeed, analysis of the radio remake of Stagecoach is helpful in revealing the quite different nature of radio programs and films as texts both aesthetically and ideologically and the quite different status of the director as an author in these two media. Whatever else may have happened on January 9, 1949, the public became acquainted with neither "John Ford's Stagecoach " nor the role of a film director.

The notion of "John Ford's Stagecoach ," as well as the concept of the role of the film director, invokes issues of authorship. I have elsewhere argued in detail that authorship in the arts can be usefully explored within Nelson Goodman's distinction between autographic and allographic arts (Lehman, 1990, 1978). Autographic arts are those, like painting, in which the hand of the artist is crucial in the creation of the aesthetic text. Forgery is thus a crucial issue since to claim that a painting is a Rembrandt is to claim a specific history for that painting—that is, Rembrandt painted it with his own hand, not someone in Tucson in 1992 claiming to be Rembrandt. If the latter is the case, we say that the painting is inauthentic. In an allographic art form, such as classical music, the hand of the artist is not an issue and there is no distinction between an original and a copy. Thus, should someone in Tucson in 1992 rush the stage during a performance of a Beethoven symphony, seize the score, and declare it inauthentic since it was printed by machine in Cleveland rather than handwritten by Beethoven, the poor soul, far from being hailed as having made an insightful discovery, would be led away and declared hopelessly confused.

What accounts for this different status among the arts? Goodman argues that allographic arts are contingent upon the existence of a notational system for the constitutive features of the aesthetic text. That is, whatever constitutes the identity of the aesthetic text must be amenable to notation.

The autographic arts have no such notational system and must be executed by the artist who creates the work. Rembrandt, in other words, could not notate an oil painting and leave it to someone else to paint. Notational systems can be understood by contrasting them with discursive language. In the former case, one and only one thing correctly corresponds to each notated mark within the system. Within classical music, for example, only one sound corresponds to each note. In discursive language, however, a limitless number of things correspond to each unit. There are many shades that correspond to the word "blue," and no matter how many other discursive words we use to qualify it (e.g., bright, extremely bright), this never changes; we can never limit the correspondence to a one-to-one relationship. In my past exploration of issues of autographic and allographic arts in relation to authorship, I have argued that comparing film and theater in particular reveals profound differences between a play script and a film script, as well as a theater director and a film director. It is necessary to briefly summarize those distinctions since I now want to argue that equally strong differences characterize writing and directing in radio and film.

No art forms lie entirely within a notational system. Thus, in classical music, discursive language such as the term "allegro" is used to supplement the notations. If a composer writes such things as "play fast" or "play with passion" on a score, those directions are not constitutive features of the aesthetic work. How one interprets or ignores such directions does not affect the identity of the work; however, playing wrong notes, leaving notes out or adding notes does affect the identity. Notational systems allow the distinction between the quality of the performance and the identity of the work; one can bemoan a poor performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 but still recognize it as Beethoven's work.

In the theater, the dialogue written by the playwright is part of a notational system, but the stage directions are part of a discursive language system. Thus, if someone playing Hamlet says, "Oh, that this too, too solid flesh would melt," he is in compliance with what Shakespeare wrote within the notational system. Only one spoken word corresponds to the notated word. To say, "Oh, that this flesh would melt," is to make a mistake equivalent to leaving out notes in a musical score. It affects the identity of the work rather than the quality of the performance. If, however, the stage directions read "exit stage left quickly" and the actor exits stage right slowly, the identity of the play is not affected. The consequences of this distinction are critical for understanding radio. Within Western theatrical tradition (there are other cultural traditions for theater, music, and all the arts), the dialogue the characters speak creates the fictional world and tells us what the play is fundamentally about. It is for this reason that the same play can bear countless interpretations with widely differing staging and, even more pertinent to our current inquiry into radio, a play can be fully compre-

hended with a staged reading. That is, the actors can be seated and not in costume. If they speak the dialogue, we can enter the fictional world of the play, understand the characters' actions and the play's themes. We need not see anything in order to identify Shakespeare's "Hamlet," and it is for this reason that we can read, understand, and even evaluate the play without ever seeing a performance of it.

Although we speak of theater and cinema in similar language (e.g., films have a script or screenplay , actors, and a director), they are in fact quite dissimilar. As with theater, only the dialogue spoken by the actors in a film is part of a notational system; camera directions, descriptions of shots and sets, and so on are discursive language. In the cinema, however, the visual image constitutes the diegesis of which the spoken word is only a small part. Dialogue in cinema, in other words, need not create the characters, describe the situations or even state the themes. Much less of the aesthetic text is amenable to notation in the cinema. It is a question of degree rather than kind, but the degree of difference is so great as to border on being one of kind. In this sense, the common expression that cinema is a director's medium rather than a writer's medium is correct.

Writers and screenplays are not, of course, useless. They occupy an intermediary stage in the process of creation. If a painter uses a photograph or a sketch in creating an oil painting, that prior image has served a useful purpose for him or her. It in no way, however, notates the constitutive features of the oil painting as an aesthetic text, though it may outline or indicate some of its features. Limitless paintings can be made using the same sketch or photograph and they can range in quality from excellent to poor—and they can be good or bad for quite different reasons. Screenplays do not notate the constitutive features of a finished film, though they may provide an outline or indication of some of those features.

The relationship between dialogue and gesture in the theater and cinema is virtually reversed. The dialogue, as we have seen, cannot be changed in the theater without altering the identity of the work. Every director staging "Hamlet" may stage it differently, however, and every actor playing the part may gesture differently than every other actor when delivering a given line. In the cinema, however, the gesturing and placement of the actor frequently are more important in the creation of the aesthetic text than the dialogue he or she speaks. In Ford's Stagecoach, for example, a scene occurs where Ringo (John Wayne) asks Dallas (Claire Trevor) to marry him. They stand close to each other, though separated by a hitching post upon which each places a hand. The aesthetic complexity of the moment derives, as we shall see shortly, from both the visual motif of the wooden hitching post and the fact that the characters are positioned on either side of it. The exact wording of Ringo's proposal and Dallas's reply is of lesser importance and, in fact, could be changed without greatly altering the film as a complex

aesthetic object. Were the actors to stand in front of a tree, however, the entire meaning and significance of the moment within a complex aesthetic text would collapse. In a very real sense, and in opposition to the theater, this can only be "staged" one way. From the point of view of aesthetics, the same screenplay filmed five different ways is not five performances of the same screenplay, but rather five different films with some similar features of story and dialogue—like five different oil paintings based upon the same sketch of an apple and a pear. It is precisely for this reason that reading screenplays is not analogous to reading play scripts and that a staged reading of Stagecoach would be an incomprehensible bore, no matter how much one liked the film. The spoken word in a film script is not a dense, complex aesthetic text as, for example, Shakespeare's "Hamlet" is. It neither creates nor sustains a fictional world, but rather may be a small part of it. The filmmaker, usually the director, fulfills the function of creating the diegesis. Which brings us finally to radio where, among all the media, the situation is once again virtually reversed; the written word does create and sustain the diegetic world and the writer, not the director, creates the aesthetic text. It is within this framework that we can best understand the radio version of Stagecoach as well as the paradox of its production by the Screen Directors Guild.

After the introduction, the radio version of Stagecoach begins with a cowboy song, then Ford narrating the story's premise about the stagecoach journey in 1885 from Tonto to Lordsburg and the dread of the dangers posed by Geronimo. "It's a story still told by the Indians," Ford says, and the narration then segues to an American Indian narrator who tells of the "mighty white invader" and the city of Tonto, where the "stagecoach stopped to take men to the Westward where Geronimo was leader, chief of the Apaches." The story begins in Tonto, where the stagecoach passengers are warned of the dangers of their journey.

The use of the Indian narrator, who is heard again during and at the end of the story, frames the events quite differently than occurs in the film, where a white narrator tells of the dangers of Geronimo at the film's beginning and is never heard from again. While the brief use of a narrator at the beginning of a film, who then never reappears, is a convention of classical Hollywood cinema, it is important here to note the consequences of the narrational shift in the radio version. The film never claims to have any sympathy with Geronimo or the Apaches; they are simply introduced from the white perspective as a threat to civilization, which is assumed to be synonymous with white culture.[2] In a somewhat bizarre manner, the radio program seems to frame the story as one told from the Apache point of view, something that receives emphasis since it is the last thing we hear Ford tell us. Certainly nothing about the film or the short story upon which it is based seems to justify such a perspective. Why would the Apaches want

to tell a story about the journey of whites? Furthermore, in Ford's film, the Apaches receive no development as human beings with their own culture; they are simply a threat synonymous with the wilderness. They emerge from it, attack the coach, and flee back into it. They do not speak and we do not even glimpse their village or way of life. If this radio program is a version of the film, we might very well wonder why the Apache would still tell this story.

The radio version offers no answer. We hear the Indian narrator during the Apache Wells scene as he tells of the gathering Apaches who are about to attack the coach. He returns at the end of the story and, in a totally unexplained manner, celebrates the "brave" white "man's" story: "Thus the story of those brave men, riders of the flying wagon, in the land of Arizona where Geronimo was chief. In the great land in the desert where the flying wagon galloped, that the white men called the stagecoach, bringing brave men to the West." In his initial appearance, the narrator spoke with respect for Geronimo's attempt to stop the "white invader." During the Apache Wells scene, he gives knowledge of what the Apaches are doing, thus at least representing their point of view. At the end, however, he is simply reduced for no apparent reason to celebrating the victory of the enemy of his people. The racism resulting from this narrational strategy is thus of a markedly different kind than that in the film.

The opening scene of the radio program establishes a major aesthetic strategy of this version, a dramatic paring down of the film's characters. Mrs. Mallory, Hatfield, Doc, and Dallas are identified as the sole passengers, with no mention of Gatewood or Peabody. Buck, so effectively characterized by Andy Devine in the film, is a character in name only here, though the sheriff, played by Ward Bond, functions similarly to the film's sheriff. Once the journey gets under way, the coach stops only once, rather than twice as in the film, and there are no characters of even minor significance introduced at the stop. Such a paring down of characters and events is to be expected within the shift from the hour-and-a-half classical Hollywood format to the half hour radio format. As in Hollywood's adaptation of nineteenth-century novels, for example, there are simply too many characters and events in the film to be included in the radio program. Some events, such as when Ringo stops the coach in the wilderness and the sheriff places him under arrest as an escapee, occur in the radio version very much as they do in the film but they take on quite different meanings than in the film.

The manner in which Ringo stops the stage and gets on it in the film has several levels of visual significance. In contrast to all the other passengers who board the coach in town, Ringo is associated with the wilderness in which he first appears.[3] When he gets in the coach, he sits on the floor with his back to the door, the wilderness visible through the window in

every shot of him. His position on the floor between the rows of passengers also visually establishes the mediatory function he fulfills: as tensions mount in the coach, rather than take sides he attempts to calm people down. In the radio program, there is no strong association with the wilderness and Ringo sits next to Dallas when he gets on the coach. Their conversation is an abbreviated but similar version of the lunch conversation they have at the first stop in the film; Ringo perceives Dallas as a "lady" and himself as a societal outcast.

At Apache Wells, the travelers learn that Captain Mallory and the troops have been sent ahead to Lordsburg, a vote is taken as to whether to go back or proceed with the journey, Dallas is overlooked in the vote, Mrs. Mallory faints, and Doc Boone is drunk when needed—in short, an encapsulated version of events from the film. Mrs. Mallory gives birth, and Dallas brings the baby to the men. Although the scene seems to parallel that in the film, it serves a different dramatic function since none of the serious divisiveness caused by such things as Gatewood's and Peabody's desire to go back is present in the radio version. Thus, the dramatic counterpoint of everyone gathering together in a rare moment of peaceful unity is absent.

The scene does fulfill the function, however, of bringing the mother/whore dichotomy into play. We are told euphemistically at the beginning of the program that Dallas is being thrown out of town because she is too "hospitable to the gentlemen." After seeing her hold the baby, Ringo later tells her, "I watched you with that baby today. You looked . . . you looked . . . well, nice." He then proposes to her and she replies, "You don't know me. You don't know who I am." These two moments of the radio program closely follow the film, even repeating dialogue, but once again, the aesthetic and ideological significance varies greatly between the two versions. Classical Hollywood cinema, of course, frequently characterizes women as either nonsexual mothers or sexualized whores, the whore with a heart of gold being a common variant. The iconography of Dallas holding the baby relates to this filmic tradition and operates specifically through point-of-view editing: the spectator, as well as Ringo and the others, is positioned to see Dallas as a mother. Furthermore, Stagecoach dramatically illustrates the mother/whore polarization within which many female characters were trapped in classical Hollywood: in an instant Dallas goes from one pole to the other and the sight of her holding the baby justifies the reversal. The extremes come dangerously close to baring the device and thus revealing the restrictive limitations of such either/or characterizations.

Similarly, the scene where Ringo proposes to Dallas receives its complexity visually through their positioning around the corral post, described above. The hitching post and the closely related image of the corral post are associated throughout the film with the very civilization that creates

such stereotypes as the good mother and the bad whore and then drives the whore out of town. The corral post figures prominently in a shot near the beginning of the film as the coach followed by the cavalry leaves Lordsburg. We see corral posts in the lower foreground of the frame, a butte looming in the center distance, and a dirt road stretching between them. The coach followed by the cavalry enters from the lower right and proceeds along the road on its journey into the wilderness. This highly formal composition, which visualizes the film's dramatic structure of a journey from civilization into the wilderness, prominently uses the corral posts to signify the last vestiges of civilization. The entrances into both of the stagecoach stops are shot in ways that similarly reinforce this post motif with the temporary safety of these isolated places of civilization in the wilderness. Similarly, the horrors of the Indian attack upon Lee's Ferry, the last stagecoach stop, are visualized in images of corral posts left standing in the smoldering ruins. Finally, the hitching post motif appears prominently in Lordsburg as Ringo and Dallas walk along and she fears his reaction when he discovers the truth about her, and as she waits alone in anguish after hearing the sounds of gunshots between Ringo and the Plummers.

It is only in the wilderness that Ringo, who first appears and boards the stage in the wilderness, can perceive Dallas freed from the stigma of her social role, but the post that divides them is a reminder of the realities of the social roles to which they must and do return. When they arrive in Lordsburg and Ringo walks Dallas "home," they once again stand with their hands on a hitching post, this time united on the same side as Ringo resolves to return to Dallas after killing the Plummer boys. In the radio program, there is no complexity to his marriage proposal equivalent to the visual reminder of society's restrictions that Ford's positioning of Ringo and Dallas, and later Dallas alone, provides. Not surprisingly, the same is true at the end of the program when they arrive in Lordsburg. When Ringo leaves Dallas to fight the Plummers, we simply hear him tell her to wait for him. It is a simple event in contrast to the complex culmination of the hitching post motif we see in the film; the way Ringo and Dallas stand with their hands on the post is a profoundly moving moment of the sort that distinguishes Ford's Stagecoach .

As in the film, after Ringo proposes to Dallas, she convinces him to escape, saying she will join him later at his ranch in Mexico. As he attempts his escape, however, he encounters Indian smoke signals and goes back to warn the others. The Indian narrator returns and tells of how his nation had to strike "the white man's flying wagon." After the narration, we return to the coach where the passengers mistakenly think they are safe. As in the film, the false sense of security is shattered by the Indian attack.

The scene is interesting in how it uses dialogue to attempt to describe action that we see in the film. "Ringo, look out! That Apache on the painted

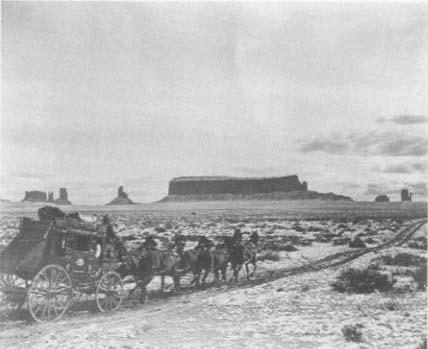

Figure 38.

Transforming John Ford's Stagecoach (1939) to a radio broadcast

raises questions about the loss of formal compositional elements.

pony," Dallas screams. We hear a gunshot and Ringo replies, "Got him." "See that Indian on that mustang coming alongside?" Doc asks. "Don't talk, shoot," someone orders and Doc responds by shooting and saying, "Well, now you see him and now you don't." This is the only place in the radio program where we hear an attempt to describe what we see in the film. Indeed, the element of visual detail (e.g., "the painted pony" and the "mustang coming alongside") is forced and out of place. It breaks with the style of the rest of the program where the characters, within the codes of realism, talk as they would in such a situation. Here they talk as if the purpose is to help us visualize the action. It is of note that the effort to supply this type of filmic visualization occurs in an action scene and is never used to recreate any of the film's visual motifs. (See figure 38.)

During the fight scene, Hatfield is killed. Ringo tells Dallas to use the last three bullets on herself, Mrs. Mallory, and the baby so that they won't be captured by the Indians. In the film, in contrast, Hatfield holds the gun to Mrs. Mallory's head as she prays and he prepares to shoot her. He is killed before he can do so and after he slumps over we hear the sound of

the bugle indicating the cavalry rescue. Indeed, Hatfield is almost able to kill Mrs. Mallory because Ringo has left the inside of the coach and, in a heroic act, jumped onto the team of horses in an effort to bring them under control. Ringo's active attempt to save the day contrasts sharply with Hatfield's resignation, and it is a contrast that has been richly developed throughout the film.

Both Ringo and Hatfield are men who live by a strong code of behavior: Hatfield is the Southern gentleman and Ringo the westerner. Although their codes are dissimilar, the two men are similar in how they adhere to their codes. Indeed, they are both driven in nearly identical fashion by those codes; Hatfield goes to Lordsburg because his code requires him to protect the Southern "lady" and Ringo goes to Lordsburg because his western code requires him to avenge his brother's death at the hands of the Plummers. In Ford's vision, the crucial distinction between these two men is that one of them enacts a code appropriate to his environment and context and the other applies an inappropriate code of conduct. This is clear in the scene where Hatfield offers Mrs. Mallory a drink out of his silver cup but refuses the courtesy to Dallas. The purpose of social codes is to ease interaction among people, but Hatfield's act merely introduces further discord into the group. Even if his distinction between the two women were valid within an upper-class, genteel Southern tradition, it is hopelessly out of place within this stagecoach in the western wilderness, but Hatfield does not perceive this. Similarly, within Ford's vision, Hatfield's preparation to kill Mrs. Mallory reflects an almost despicable failure of masculine western courage and action. He should be risking his life in battle with the Indians rather than fatalistically preparing to kill a woman. For this reason, it comes as a relief to the film audience when Hatfield slumps over dead. In the radio program, however, Hatfield's death is of little significance, and the way in which Ringo fulfills the function of saving the women from the "fate worse than death" has no more significance in relation to his character.

A description of this scene indicates how the film director can create a dense visual and aural text around a simple narrative event. In one shot, we see Mrs. Mallory praying fervently as a gun from off screen left enters the frame and points at her head. She appears oblivious to her impending death when suddenly the gun drops slowly downward and finally drops out of the frame. Mrs. Mallory continues praying and we hear the sound of a bugle blowing off screen. Her facial expression changes from fear to hope as she realizes the significance of the impending cavalry rescue. Narratively, the moment is not only simple but even clichéd—it is the classic last-minute cavalry rescue. What distinguishes it, however, is Ford's beautiful use of offscreen space. We never see Hatfield as he prepares to shoot Mrs. Mallory or when he himself is actually killed; we infer his death from the dropped gun. This shot begins by being structured visually around offscreen space

then ends by being structured aurally around offscreen space: we hear the bugle before we see the cavalry riding to the rescue. A conventional cutting pattern showing Hatfield prepare to shoot Mrs. Mallory, then being hit himself, followed by a direct cut to the cavalry riding to the rescue while we simultaneously hear the bugle would rob this scene of its distinction.

The bugle signals the rescue in the radio program as in the film, and the last scene takes place in Lordsburg. The scene bears careful analysis because it is by far the most aesthetically complex in the radio program, and the nature of that complexity reveals much about the relationship of radio narratives to film narratives. After Ringo tells Dallas to wait for him and goes off to seek the Plummers, Dallas says a prayer. We hear distant shots as her prayer continues, followed by the cowboy song heard at the program's beginning and finally the sound of footsteps heard from Dallas's perspective. Dallas emotionally asks, "Who . . . who's that out there?" and then she happily exclaims, "Ringo!" The scene unexpectedly draws upon the nondiegetic sound element of the cowboy song that had previously been perceived as simple introductory music, as well as draws on elements of diegetic sound perspective from the position of the character around whom the scene is structured, and it further layers those sounds with the foregrounded sound of Dallas's prayer.

The final scene is perhaps the only scene in this remake that achieves a life of its own. Whereas many of the scenes seem to be lesser versions of story elements taken from the original, totally stripped of their visual, thematic, and dramatic complexity—or as in the fight scene, failed efforts to create filmic visual equivalency—the final scene creates an aural density that is, simply put, good radio. Although it takes from Ford's film the idea of Dallas waiting and finally hearing Ringo's footsteps before identifying him, it develops the concept in an original way. In the film, for example, we see Ringo engaged in his fight with the Plummers. Structuring the scene entirely around Dallas waiting intensifies one element of the dramatic structure in the original and makes it the primary organizing principle.

The last scene concludes when Ringo tells Dallas that before dying Luke Plummer confessed that he killed Jed Michael, the crime for which Ringo has been in jail. He is now a free man. Dallas cries in response and Ringo asks despairingly, "Dallas, what are you crying for?" and naively adds "Nothing's happened." On this happy note, the previously discussed narration concludes the program. In the film, Luke Plummer doesn't confess and the sheriff turns the other way to allow the guilty Ringo to "escape" with Dallas to his ranch in Mexico where they will be spared "the blessings of civilization." Since the radio program entirely lacks the film's rich development of the ironic treatment of civilization's blessings, the happy ending makes perfect sense. It is central to Ford's film that Ringo and Dallas have to flee

civilization since civilization lacks the flexibility and complexity to perceive them in a different light. They remain the escaped convict and the whore.

Clearly, the radio program does not present "John Ford's Stagecoach ." Indeed, it is hard to talk about it as either a remake or an adaptation of Ford's film. If anything, it adapts the outline of some of the major story elements and a few fragments of the dialogue but, as I have argued, it is in the nature of film that those elements only constitute a small portion of the finished filmic text. In other words, those are the simple elements that do not create a dense aesthetic text in themselves as they do in theater but that may be used in the creation of such a text. The radio version of Stagecoach fails to create a rich aesthetic text not because of anything about the nature of radio, as the exception of the fight scene shows, but because most of this program is content to merely re-present simple story elements from the film. It is also in the nature of radio, however, that if Ford were to have directed this script it would have made little or no difference since the writing creates, shapes, and sustains radio's diegetic worlds. Radio directors have little to do except shape vocal performance and sound effects. If we had five different versions of the same radio script of Stagecoach by different directors we would have five different versions of performances of the same work. In contrast to cinema, the identity of the work clearly lies with the writer, not the director.

The Directors Guild seems to have perceived this paradox since the directors did not direct the radio programs. If in fact one wants to present the director to the public, this would be the logical manner. But since the directors would not be involved in an analogous directorial activity, they were simply presented to the public as personalities who introduced the program and reminisced about the original film. The way in which each director is announced at the beginning of the program as the "director" betrays the confusion. Even if they were the directors of the programs, there would, in the filmic sense of the term, be little or nothing for them to direct. The situation would be quite different in the mid-fifties when the Screen Directors Guild became involved with television and the Screen Directors Playhouse . In 1955, John Ford directed Rookie of the Year . Rather than a remake of a film, the program was an original drama. Both the guild and Ford perceived that in this medium there was a creative role for the film director; he need not simply be briefly presented to the public. Presumably, he was making something rather than remaking something for a different medium. Yet, the guild and the film directors may have seen more commonality between directing in these two media than actually exists. How television directing compares to film and radio directing is, however, another story for another time.

If the Screen Directors Guild's promotion of film directors on radio was

a strange aesthetic paradox, from the economic perspective it made good sense. The guild quite correctly perceived that radio, and later television, could be used to promote and stimulate interest in films. The announcer says at the end of the broadcast of "Stagecoach," "John Wayne can soon be seen in John Ford's Argosy Production Three Godfathers , and Claire Trevor appears in the soon-to-be-released Amusement Enterprises picture The Lucky Stiff . Ward Bond is currently appearing in the Victor Fleming production Joan of Arc ."

And one last thing. If the public was not treated to "director John Ford's Stagecoach " on January 9, 1949, whose remake was it? During the closing credits of the show, we are told, "Tonight's story was adapted by Milton Geiger." From the point of view of aesthetics and authorship, the announcer should have proclaimed at the beginning, "Tonight your creator is Milton Geiger" rather than "Tonight your director is John Ford." What the significance of that would have been in 1949 is unclear. Unfortunately, given the scholarly lack of interest in radio aesthetics, it is still unclear today.

Special thanks to Warren Bareiss for sharing his knowledge of radio and his resources with me.

Works Cited

Baxter, John. The Cinema of John Ford. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1971.

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990.

Buscombe, Edward. Stagecoach. London: British Film Institute, 1992.

Dunning, John. Tune in Yesterday: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Old Time Radio. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

Goodman, Nelson. Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968.

Lehman, Peter. "Script/Performance/Text: Performance Theory and Auteur Theory." Film Reader 3 (1978): 197–206.

———. "Texas 1868/America 1956." In Close Viewings: An Anthology of New Film Criticism , edited by Peter Lehman, 387–415. Tallahassee: Florida State University Press, 1991.

McBride, Joseph, and Michael Wilmington. John Ford. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975.

Place, J. A. The Western Films of John Ford. Secaucus: Citadel Press, 1974.