Cinema and the Comics:

Two Visual Languages

March 22, 1895: the Lumière brothers project their first films to a private audience. February 16, 1896: the "Yellow Kid," the first successful comic strip character, makes his first appearance in the New York newspaper World .[4] Born less than one year apart, the two narrative media made possible by the advent of the age of mechanical reproduction then went on to widely different futures. Cinema was to become the only medium dependent upon the technological revolution of the last two centuries to be admitted into the hallowed halls of art (the "tenth muse," as it has been called), whereas the comics remained for most of their history the point at which "Art" turned her eyes with horror, the point of no return beyond which lies the realm of hopelessly and irredeemably "popular" culture. The appropriation of cinematographic techniques by comics artists has been often remarked upon.[5] Nevertheless, the relationship is not necessarily one-way. John Fell has pointed out that early filmmakers and comics artists were confronted with "common problems of space and time within the conventions of narrative exposition" (89), and that the comics developed a highly sophisticated language that in some cases anticipated cinematographic solutions to these common problems. For their part, a number of film directors, including Federico Fellini, Orson Welles, and George Lucas (Inge, xx) have acknowledged an interest in and even a debt to the comics.[6]

Cinema and the comics are both primarily visual languages. Comic writer and artist John Byrne has remarked recently that "good art will save a bad script, whereas good writing can do little to save bad art," a statement especially to the point in regards to recent mainstream comics (particularly the superhero genre) in which an increased aesthetic awareness on the part of artists has been accompanied by an almost opposite trend in plots. Both media construct a story through the juxtaposition of images, so that the relations established among them can convey the illusion of temporal and spatial development. Like cinema, a comic narrative is assembled through the succession of frames; however, whereas in film the quick succession of the frames can give the impression of actual movement, the comics have had to devise other solutions to represent movement and progression. As Daniele Barbieri explains in his excellent structural study of the comics medium, the panel itself is not simply an image frozen in time, but it can be used to represent a duration through a number of different techniques (use of motion lines, repetition of the image as with an overexposed pho-

tograph, particular arrangements of the balloons, and sound effects, etc.): "Therefore, we have one image—traditionally corresponding to one instant—within which there is a duration. With the comics, the panel no longer represents an instant , but a duration: just like cinema (230–31)."[7]

If we take this definition of the comic panel, perhaps we can establish a more useful comparison between it and the cinematographic shot as the basic unit of composition of the two media. In film, meaning is generated by the syntagmatic relation of the shots in a sequence: like the combinatory elements of articulated language, the shots are arranged along a space that is "linear and irreversible" (Barthes, 58), the previous shot preparing the viewer for a range of possibilities in the following one. To quote Roland Barthes again, "[E]ach term derives its value from its opposition to what precedes and what follows" (58). Likewise, the panels that compose the comic page, traditionally arranged for reading from left to right, from top to bottom, construct meaning by their relation to one another. However, this syntagmatic reading is paralleled by "a paradigmatic reading of inter-relationships among images on the same page" (Collins, 173), allowing for effects that are not available to cinema and that make up for the relatively static nature of the comics.

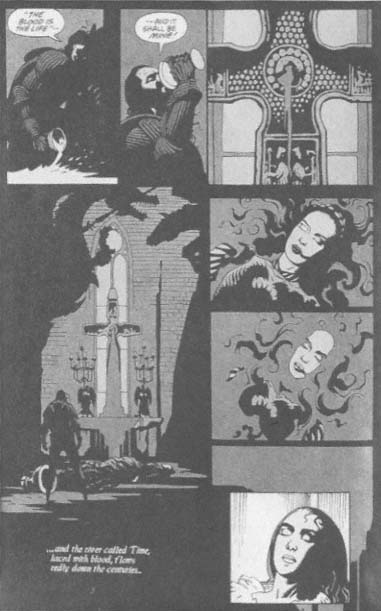

As an example, let us discuss a page of the comic book adaptation of Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula (1992), published by Topps Comics (story by Roy Thomas and art by Mike Mignola). The page reproduces the crucial scene in the frame story of Dracula's origins (so much for Bram Stoker's Dracula ). In the film, the count stabs the cross on the altar with his sword; from the gash in the wood blood starts pouring out, until it covers the whole floor of the church and submerges the body of Dracula's dead wife, Elisabeta.

The first striking element about the comic book adaptation is the page itself: the border that surrounds the panels is not white, as is common with most comics, but black. (See figure 37.) This technique can be used very effectively to connect the panels, as the borders are not as clearly demarcated. In particular, in the long panel on the bottom of the left half of the page the shadows of the gargoyles blend in with the darkness of the frame so that the latter seems to be an extension of the shadows of the church (this sense of continuity between panel and border is reinforced by the trickle of blood that reaches the edge of the page). Therefore, the smaller panels appear superimposed on this larger one, which comes to include the whole of the page.

The first two panels give a good example of how the illusion of movement can be created through static images. In the first, Dracula dips a cup in the holy water spilled in the previous page. In the next, he is shown raising the cup to his lips. In following the cup from the bottom half of the first panel to the top half of the second, the eye goes through the same

Figure 37.

The comic book transformation of Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula

offers imaginative "takes" on the film. Courtesy of Topps Comics.

movement as the cup lifted from the ground to the count's lips. The illusion of continuity and trajectory is reinforced by the little drops of water splashed in panel one in the direction of panel two.

The next panel presents a frontal close-up of the cross, out of which blood starts flowing. Now, in a syntagmatic reading of the sequence the successive panel is the long left-hand one mentioned above. Here, the "camera" pulls back to a long shot that reveals Dracula facing the cross, his wife lying dead on the steps of the altar on which the cross is mounted. Then follows a close-up of the dead woman's face. However, the third and fifth panel can also be read vertically (a reading encouraged by the vertical thrust of panel four, and by the fact that the following panel, panel six, is directly below five rather than next to it). Thus, the blood gushing out of the cross seems to be pouring directly over Elisabeta's face, partially covering it in panel six, and finally drowning it out in panel seven. In fact, by its very shape, panel seven continues the flow of blood that started four panels above: its top edge and part of its sides are straight lines, but instead of closing into a square, as with a regular panel, they taper into the shape of a dripping red strip of blood, eventually cut off by the edge of the page itself. The blood that in the film covered the whole screen here flows throughout the page, and beyond it. Finally, in a device that may be as close as comics can come to a lap dissolve, an eighth panel is superimposed on the seventh.[8] Through it, we are carried forward in the narrative outside the frame story and into 1897 London, but the panel itself is used to establish a clear link between the two parts of the narrative, since it represents Mina's face in roughly the same position as Elisabeta's in panel five. (As we know, in Coppola's version of the story Mina is a sort of reincarnation of Dracula's beloved wife.)

Although my analysis is concerned with one single page, I would like to point out that, as Witek has suggested, "[t]he largest perceptual unit of comic-book storytelling is the two page spread (20)."[9] In fact, in the first panel of the facing page the "camera" moves back to give a full shot of Mina in a washtub, her face in the same position as in the last panel of the previous page. Above her, Lucy pours water over her head, a gesture that looks back to both Dracula filling the cup with holy water and the blood pouring out of the cross on the opposite page.