Plates

Plate 1.

Historical Museum, Moscow, north facade, facing Okhotnyi Raid. Left : Moscow City Duma. 1890–1892.

Dmitrii Chichagov.

Plate 2.

Court Church of SS. Peter and Paul, Peterhof.

1895–1904. Nikolai Sultanov.

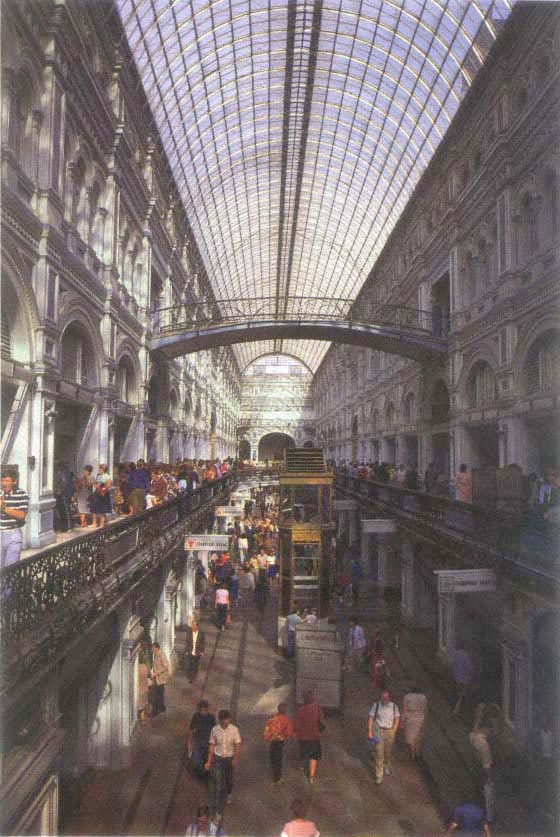

Plate 3.

Upper Trading Rows, Moscow. 1889–1893. Vladimir Pomerantsev. Central arcade.

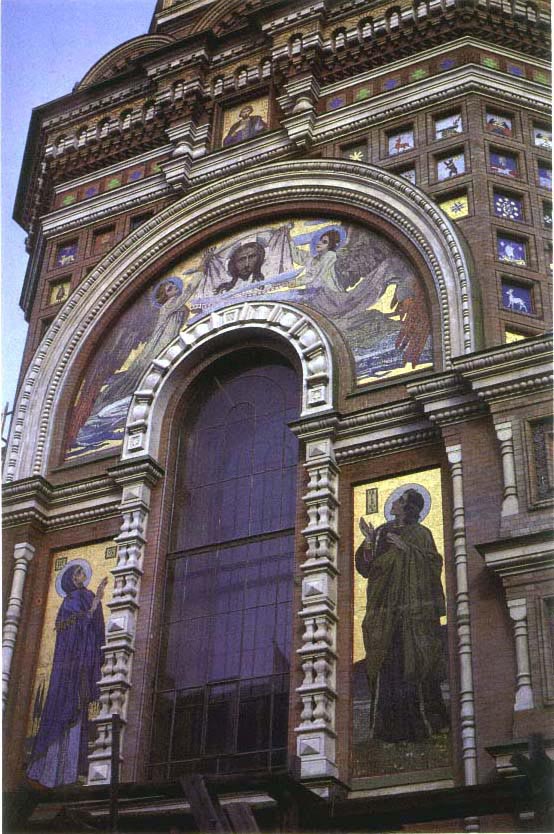

Plate 4.

Church of the Resurrection of the Savior on the Blood, Petersburg. 1883–1907. Alfred Parland.

Detail, west facade.

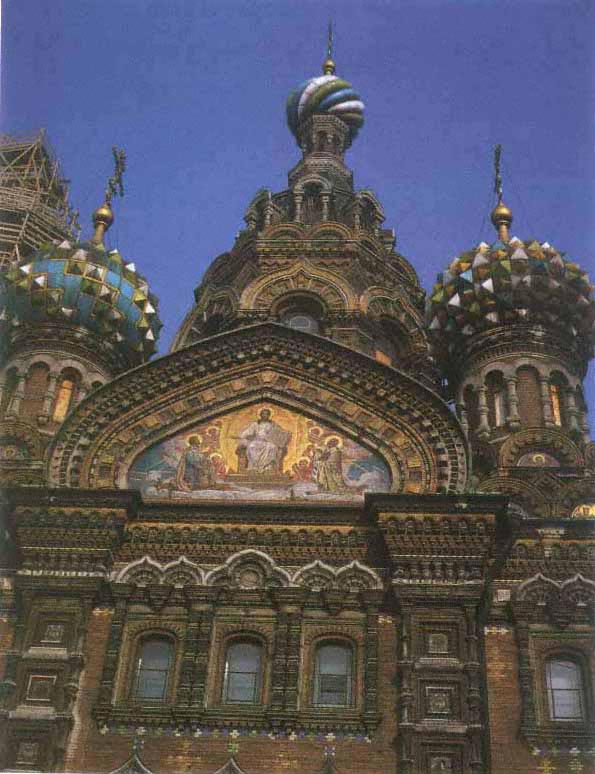

Plate 5.

Church of the Resurrection of the Savior on the Blood, Petersburg, detail, south facade.

Plate 6.

Church of the Icon of the Savior, Abramtsevo.

1881–1882. Viktor Vasnetsov.

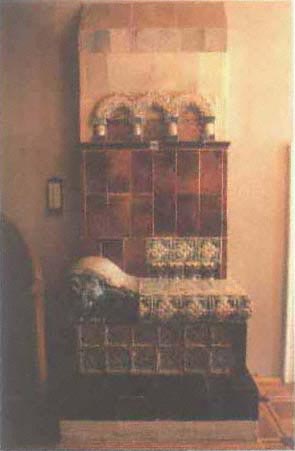

Plate 7.

Ceramic stove, Abramtsevo. 1890s. Mikhail Vrubel.

Plate 8.

Hotel Metropole, Moscow. 1899–1905. William Walcot. Ceramic panel "The Princess of Dreams" by Mikhail Vrubel.

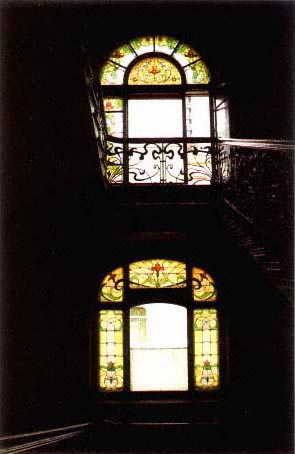

Plate 9.

Hotel Natsional, Moscow. 1901–1903. A. I. Ivanov.

Stained glass, main stairway.

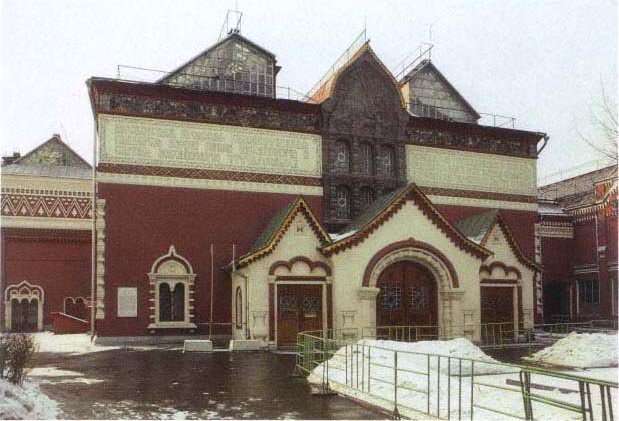

Plate 10.

Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow. 1902–1905. Viktor Vasnetsov.

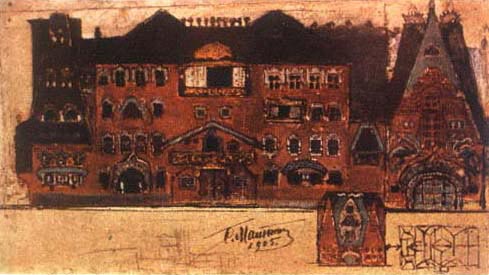

Plate 11.

Project sketch for Pertsov apartment building, Moscow. 1905. Sergei Maliutin.

Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1907.

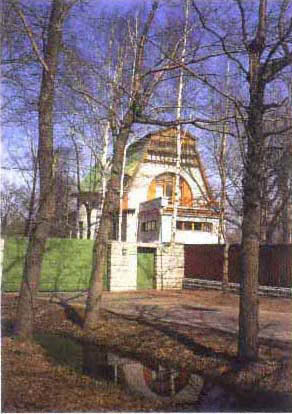

Plate 12.

Pertsov apartment building.

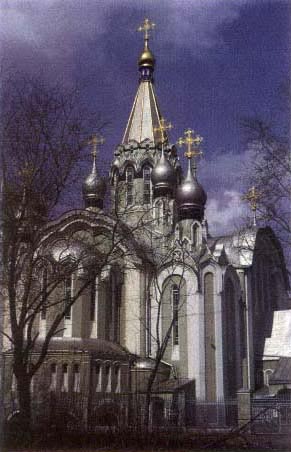

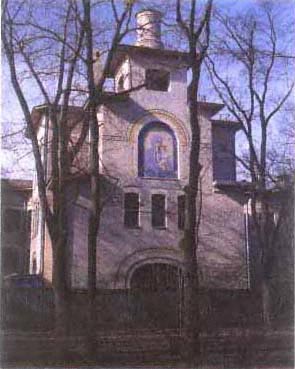

Plate 13.

Church of the Resurrection in Sokolniki, Moscow.

1909–1913. P. A. Tolstykh.

Plate 14.

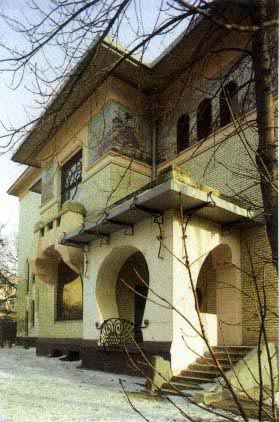

Riabushinskii house, Moscow. 1900–1902. Fedor Shekhtel.

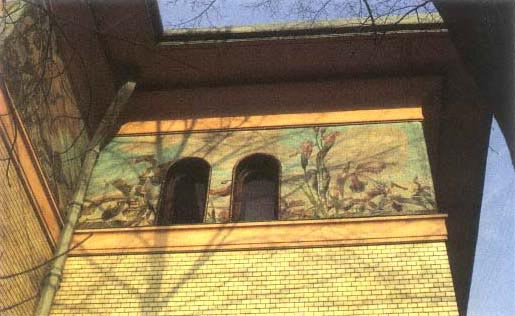

Plate 15.

Riabushinskii house, mosaic detail.

Plate 16.

Riabushinskii house, side facade.

Plate 17.

Riabushinskii house, central space.

Plate 18.

Riabushinskii house, stained glass window, upper level.

Plate 19.

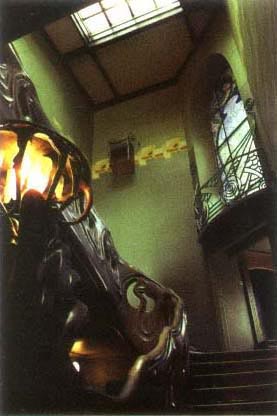

Riabushinskii house, main stairway.

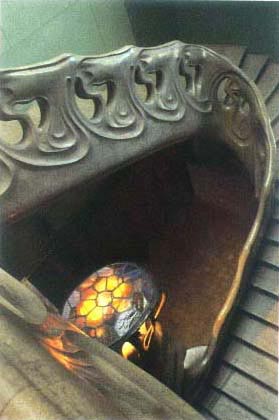

Plate 20.

Riabushinskii house, main stairway.

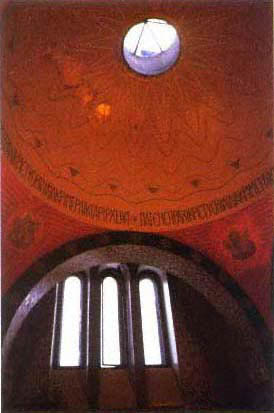

Plate 21.

Riabushinskii house, chapel.

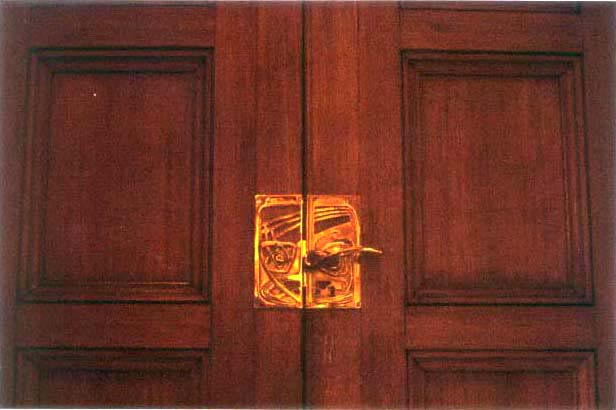

Plate 22.

Derozhinskaia house, Moscow. 1901. Fedor Shekhtel. Door handle, main hall.

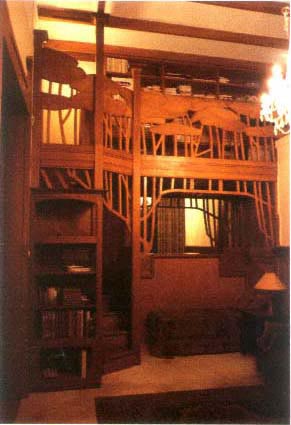

Plate 23.

Derozhinskaia house, library.

Plate 24.

Moscow Art Theater. 1902. Fedor Shekhtel. Right entrance.

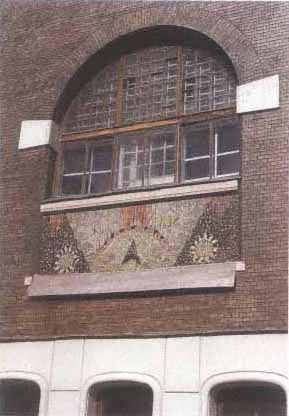

Plate 25.

Iaroslavl Station, Moscow. 1902. Fedor Shekhtel.

Plate 26.

Iaroslavl Station, ceramic detail, side facade.

Plate 27.

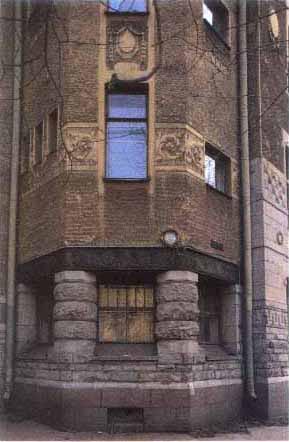

Lidval apartment house, Petersburg. 1899–1904.

Fedor Lidval. Detail.

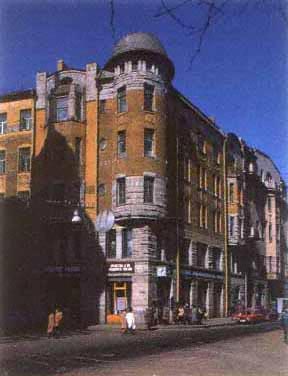

Plate 28.

Meltser Building, Petersburg. 1904–1905. Fedor Lidval.

Plate 29.

Apartment house, No. 159 Fontanka Quay, Petersburg. 1910–1911. Aleksei Bubyr.

Plate 30.

Apartment house, No. 21 Bolshaia Dvorianskaia Street, Petersburg. 1911. Karl Baldi.

Plate 31.

Shults apartment house, Petersburg. 1901–1902. Karl Shmidt.

Plate 32.

Schöne house, Stone Island, Petersburg. 1902–1904.

Vasilii Schöne.

Plate 33.

Orthopaedic Institute, Petersburg. 1902–1905.

Roman Meltser.

Plate 34.

E. I. Nabokova house, Petersburg. 1901–1902.

Mikhail Geisler.

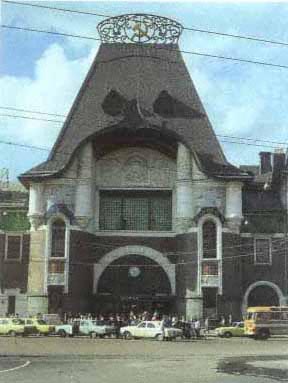

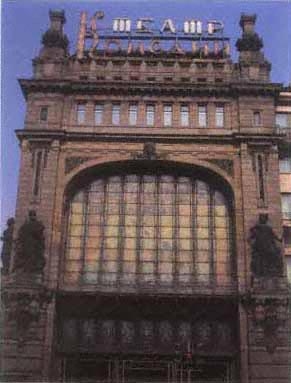

Plate 35.

Eliseev Building, Petersburg. 1902–1904. Gavrii

Baranovskii.

Plate 36.

Chapel of the Blessed Kseniia, Vasilevskii Island, Petersburg. 1900. Valentin Demianovskii.

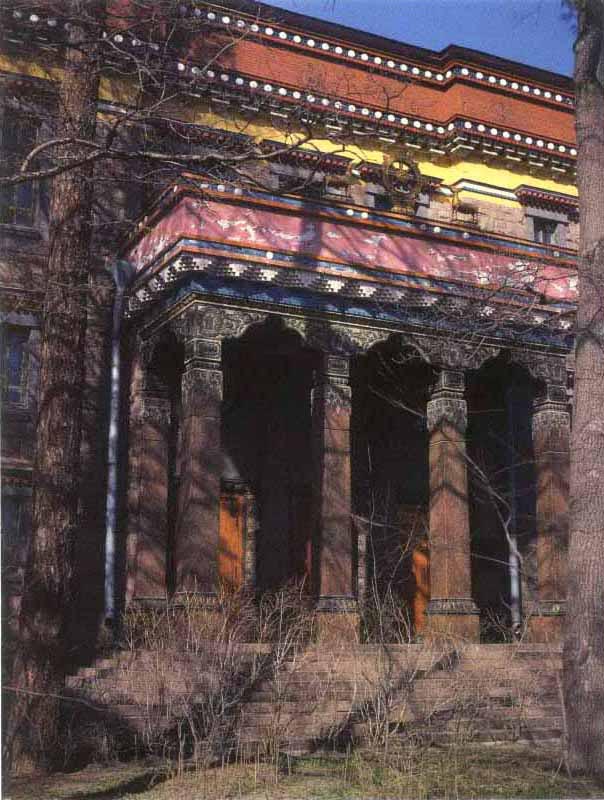

Plate 37.

Buddhist Temple, Petersburg. 1909–1915. Gavriil Baranovskii.

Plate 38.

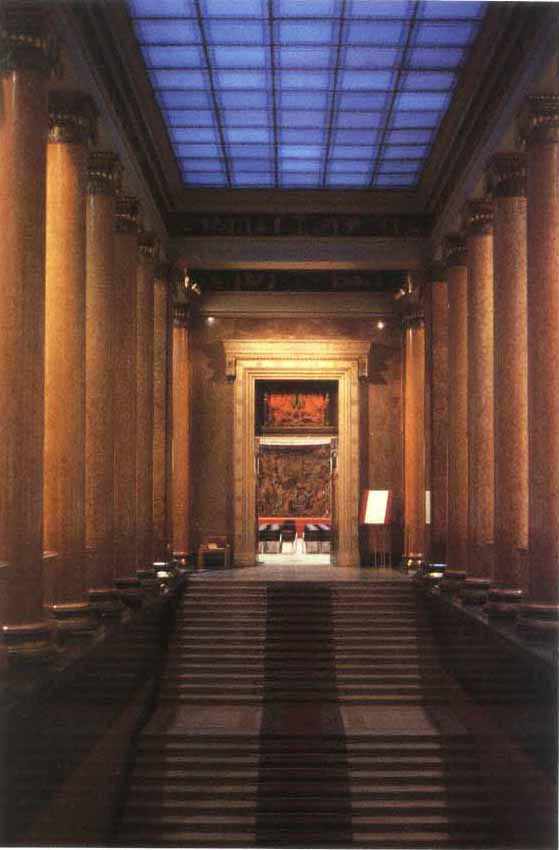

Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Interior. 1897–1912. Roman Klein.

Plate 39.

Iusupov Mausoleum, Arkhangelskoe. Interior. 1911–1916. Roman Klein.

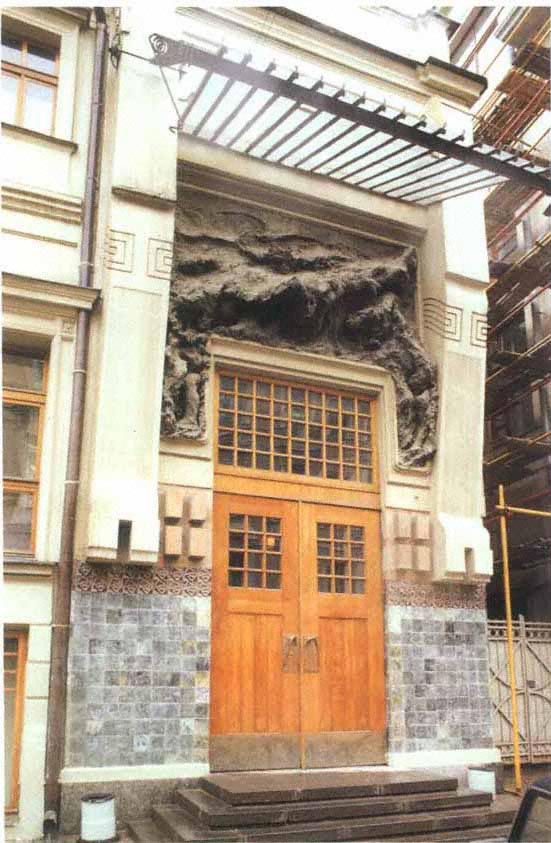

Plate 40.

Savvinskoe Podvore building, Moscow. 1907. Ivan Kuznetsov. Detail, main facade.

windows with simple mullions on the second floor and in the corner tower, and a large venetian window at the center of the front facade. The only curves appear in arches over the first-floor windows; there is not a single bent mullion among them. The few ornaments on the exterior show similar restraint, although Shekhtel did not apply them timidly. A broad frieze with an abstract botanical pattern stretches along the upper part of the front facade and wraps around the corner tower, emphasizing the shape of the structure. One can see a remnant of the Riabushinskii design in the width of the frieze, but the polychromatic whimsy has vanished.

On the back of the house, dark tiles contrast with light brick (Fig. 171), the material whose properties are most thoroughly explored in the precise lines and rounded towers of the villa. The combination in the brick of aesthetic and functional qualities underscores the movement toward a new architecture, devoid of ornament, as in the design of the Shamshin apartments and the Moscow Merchants' Society building. This development in Shekhtel's work of the 1900s conforms to a later phase of the style moderne. As Kirichenko has noted: "The moderne evolves from the representational to the abstract and nonrepresentational form, from the plastic and organic to visually strict forms and relatively strict compositions with measured divisions and repetitions, with hard machine lines and shapes."[67] At the same time the picturesque silhouette of the house suggests that traditional forms remained a source of inspiration—as Shekhtel's subsequent projects were to demonstrate.

Before he returned to a sustained use of the neo-Russian style, Shekhtel at the end of 1909 experienced a classical interlude related to, but not defined by, the contemporary neoclassical revival in Moscow and Petersburg. The scale of the two buildings in question—Shekhtel's house on Bolshaia Sadovaia Street (part of the Garden Ring) and the Chekhov Library and Museum in the southern town of Taganrog—is intimate, and both structures involved a deeply felt personal meaning. That Shekhtel should build a memorial to his friend Chekhov in the same style as his own house suggests an empathy expressible only through the traditional verities of classicism. The semiotic element in the classical design of Shekhtel's house is affirmed by the low-relief panel over the arch leading to a courtyard at the side of the house: it portrays Pallas Athena flanked by the muses of architecture, sculpture, painting, and music (Figs. 172, 173).[68]

This is not to imply that either in the house or the Chekhov museum Shekhtel reproduced neoclassical models precisely. The Petersburg critic Vasilii Kurbatov decried the tendency of contemporary neoclassical revivalists to derive excessive and trivial ornamentation from early nineteenth-century buildings (see chapter 6). But in Shekhtel's case he gave his qualified approval: "Only at the Shekhtel house are the Empire details applied entirely appropriately; that is, each one is surrounded by sufficient free space, although in its basic idea the facade has nothing in common with Empire."[69] This brief appraisal reveals Shekhtel's use of classical elements to define a complex system of spatial relations in a deceptively modest structure. The main hall, which establishes the proportions of the other rooms of the house, is given proper weight on the exterior by a classical portico, while the more modest rooms on either side are marked on the facade by windows with dimensions appropriate to their scale.[70] The entire structure is developed within a system of proportions determined by the constraints of a narrow urban lot.

During the next few years Shekhtel adapted the classical revival to other, commercial, projects including the Ice Palace (1912) on Arbat Square. This grandiose structure, centered on a large two-storied arch with a Doric portico, contained a cinema with six hundred seats (the Art Electro-Theater) as well as a skating hall surrounded by an arcaded gallery whose columns supported a trussed metal roof.[71] The Ice Palace, although not built to the original specifications, represents the extreme point of Shekhtel's classical phase, with classical statuary—Apollo and racing chariots—above the cornice of the central block (Fig. 174). In contrast to this rhetorical use of classical elements, Shekhtel's 1915 design for an exhibition hall on Kamerger Street (near the Moscow Art Theater) uses a few details of the classical entablature to adorn what is otherwise a functional grid typical of his commercial structures.[72]

Although Shekhtel adapted the vocabulary of the neoclassical style to domestic and commercial architecture, in most of his work between 1908 and 1914 he reinterpreted traditional Russian architectural forms. Many of his projects after 1907 were built in or designed for provincial cities such as Nizhni Novgorod, which perhaps were closer to the national "spirit" than Petersburg and Moscow. (The design for the Kazan Railway Station in Moscow is a notable exception.) Shekhtel's headquarters for the S. M. Rukavishnikov firm in Nizhni Novgorod (1908–1912) combines old Russian

Fig. 172.

Shekhtel house, Moscow. 1909. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1910.

Fig. 173.

Shekhtel house, entrance to courtyard (Brumfield

M102-10).

Fig. 174.

Project for Ice Palace, Moscow. 1912. Fedor Shekhtel Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1912–1913.

elements with what might be called Hanseatic medieval, yet in its grid and plate glass the structure maintains the functional approach to commercial architecture.[73]

In the same city, Shekhtel's project for a branch of the State Bank (1910) shows less ornamentation but greater depth in its arrangement of volume. The focal point of the design is a corner tower, in the style of medieval Russian kremlins, that not only contains the main entrance but also serves as a pivot for the office blocks that extend at oblique angles in an asymmetrical arrangement (Fig. 175). Although the blocks are only two or three stories high, their steeply pitched roofs form a picturesque silhouette. In contrast to the Rukavishnikov building, the decoration is restrained, consisting primarily of a strip of recessed squares (shirinki ) and other traditional ornamental patterns.[74]

Although Shekhtel's project for the bank was not accepted, the basic plan resurfaced in 1913 in his design for the Nizhni Novgorod Provincial Museum—dedicated to the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty. The front block (Fig. 176) is capped with a high tent roof similar to that of both Shekhtel's pavilions at Glasgow and the Iaroslavl Station; the side block adheres to the more modest outlines of the bank project. Shekhtel devoted special attention to the artistic formulation of the interior, which was to have had extensive wall paintings.[75]

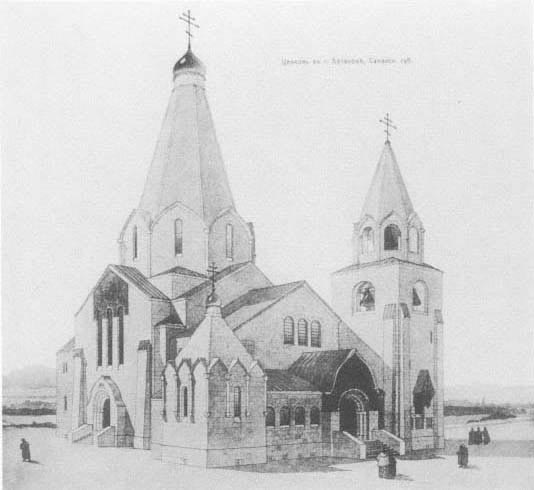

The third of Shekhtel's large projects (all unbuilt) in the Russian retrospective style was his design for the Kazan Railway Station on Kalanchevskii Square (1911). With its towers and pitched roofs, the station resembles both the Glasgow pavilions and the blocks of the Nizhni Novgorod bank. The decorative detail on the facade derives primarily from the late seventeenth century, when ornament was heavily used in Russian architecture; yet the horizontal sweep of the building and the large area devoted to windows—of many sizes and shapes—suggest that functional principles were applied in the design and illumination of the large waiting halls (Fig. 177). The tall square clock tower resembles numerous adaptations of the campanile in railway stations throughout the West (Shekhtel knew the one in Eliel Saarinen's 1904 design for the Helsinki Railway Station).

Had he won the competition, Shekhtel would have had the unique honor of designing two major stations facing one another—both drawing on historical motifs, both arranging space functionally, both emphasizing points of entry with large arched portals, and both exploiting the free style to create an asymmetrical structure. The Iaroslavl Station, however, is more unified, not only in its contoured outline (the sprawling Kazan Station exhibits a multiplicity of shapes) but also in its proclamation of modernity—traditional decorative elements notwithstanding. Each of the projects has a picturesque facade, but the Kazan Station—based

Fig. 175.

Project for State Bank, Nizhni Novgorod. 1910. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1910–1911.

Fig. 176.

Project for Nizhni Novgorod Provincial Museum. 1913. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1914–1916.

Fig. 177.

Project for Kazan Railway Station, Moscow. 1911. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1910–1911.

on seventeenth-century monuments in Kazan and Moscow—represents a clear retreat from the aesthetics of modern design. Of the remaining choices, rationalism and retrospection, Shekhtel chose the latter—as stipulated by the design competition. In the event, the winning design by Aleksei Shchusev was similar to Shekhtel's in concept and reproduced seventeenth-century prototypes even more closely.[76]

Although a number of his projects were rejected between 1910 and the outbreak of war, Shekhtel experienced success in one area that had long claimed his attention—the design of churches.[77] Unlike his earlier churches, with their conservative architectural form (usually in the neo-Byzantine style), those from 1910 to 1914 used traditional Russian prototypes in a modern interpretation. This melding of tradition and innovation also characterized the work of Shchusev, Bondarenko, and Pokrovskii, all of whom turned to pre-Petrine architecture for inspiration in designing churches.

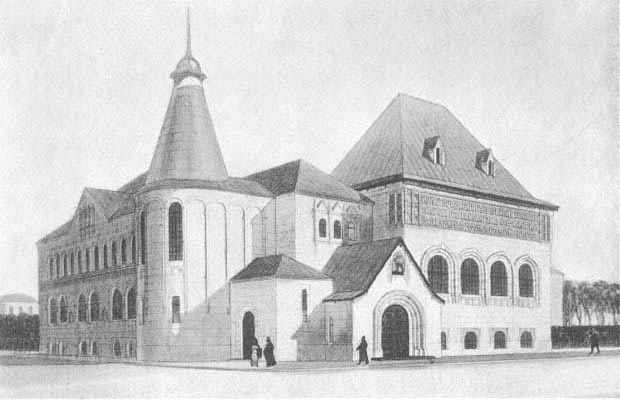

For Shekhtel the sixteenth-century tower church, with its elongated pyramidal tent roof, was the quintessential expression of the centrally organized structure; he used the tent-tower motif in the pavilions at the Glasgow exposition as well as in smaller structures in the 1890s. In his 1910 design of an Old Believer church at Balakovo (on the Volga River between Samara and Saratov), Shekhtel restored the motif to its semiotic function as a feature of the Russian church before the schism, or raskol , of the mid-seventeenth century.[78] The ashlar structure, with attached bell tower, follows the cross-inscribed plan, but the freely interpreted tent tower (here over a large cuboid structure) and subtle additions to the central cube convey an innovative approach to the medieval form (Fig. 178).

Shekhtel's final church, built in 1914 in the Moscow suburb Petrovsko-Razumovskoe, is his most sensitive and faithful re-creation of a traditional architectural form. Dedicated to St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker, the church took its shape from the most popular Russian building material—wood.[79] Shekhtel's ingenuity in wooden construction had been demonstrated at Glasgow. The church, understandably, does not have the decorative profusion of the pavilions, but the adherence to the forms of the traditional wooden church is so rigorous—a tent-roofed octagonal tower over a square—that one might assume the building to be a replica.

In fact the shape of the building (not extant), with its plank siding, placed a modern emphasis on fluid contours, from the central tower to the large extensions (each with its own roof) on the north, south, and west

Fig. 178.

Sketch of Old Believer church, Balakovo. 1910. Fedor Shekhtel. Zodchii , 1911.

(Fig. 179). The spatial unity of interior and exterior was complemented by the iconostasis and furnishings, which Shekhtel also designed (Fig. 180). Like Viktor Vasnetsov at Abramtsevo some three decades earlier, he found in the church the ideal way to integrate structure and the decorative arts.

Prerevolutionary photographs of the building show an exquisite interior, contrasting the elaborate carving of the iconostasis with the pattern of unpainted knotty pine for the walls. Shekhtel stated his fondness for this project in messages on photographic postcards showing the church. To one of his nephews he wrote: "If you should by chance meet a devotee of the Russian northern style, give him this, my favorite little church, which worked so well for an atheist such as myself." His postcard to the architect and designer Ivan Mashkov said simply: "In my opinion this is the best of my buildings."[80]

After 1914 the strain of the First World War on the Russian economy led to a sharp decline in architectural commissions (apart from military and industrial projects) and the virtual collapse of the private housing market. Shekhtel had received few commissions even in the years just before the war, but his financial position was secure, and he still worked for those who had supported him earlier in his career. At some point between 1910

Fig. 179.

Church of St. Nicholas, Petrovsko-Razumovskoe, near

Moscow. 1914. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1914–1916.

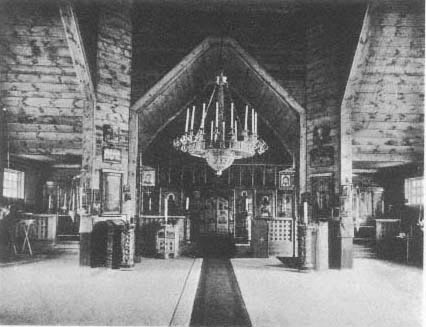

Fig. 180.

Church of St. Nicholas, interior. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1914–1916.

and 1914, he rebuilt the two-storied manor house on the estate of Gorki (south of Moscow) for Zinaida Morozova-Reinbot—the widow of Savva Morozov—for whom he had designed the first of his major houses in Moscow.[81] Shekhtel interpreted the neoclassical revival in this project so unobtrusively and harmoniously that at first glance the design seems a product of an earlier period; yet such details as the portico for this stuccoed brick building (dating from the end of the eighteenth century) and the classical frieze beneath the cornice are subtle, stylized references to Russian neoclassicism.

During the war Shekhtel's project designs ranged from a sanatorium in the Crimea to an apartment house not far from the Levenson printing works in Moscow.[82] None of these were built, and after the revolution his livelihood, like that of many artists and intellectuals, became tenuous. Moreover, Shekhtel and his family were evicted from their house, which was expropriated by the state in 1918. A fragment from the memoirs of Ilia Bondarenko, once Shekhtel's apprentice but in 1918 the director of the Office for the Preservation of Monuments of Art and Antiquity, suggests the destitution of Moscow's architects at that time:

Architects came eagerly to the office; they had little to do. My former chief, F. O. Shekhtel, arrived and asked to be assigned any sort of work. I assigned him to investigate grave markers in Moscow cemeteries, where there were still many interesting structures and statuary that had to be preserved and restored. Shekhtel carried out a few surveys and sketches, but the matter did not go beyond that.[83]

The best of Moscow's cemeteries indeed warranted preservation, and Shekhtel had earlier designed some remarkable examples of funerary art (mausoleums, grave markers).[84] Nonetheless, Bondarenko's account suggests that Shekhtel was less than enthusiastic about make-work. He did not, however, fade from view, nor did he reject the new era. Among his many professional duties, he served as president of the Moscow Architectural Association (a post he had held since 1906) and for a brief period (1921–1923) directed the Architectural and Technical Council of the Committee for State Construction.[85]

His projects between 1921 and 1925 (during the economic revival of the NEP years) included an optical factory near Moscow, with detached houses for the workers; the Turkestan pavilion at the first Agricultural Exhibition in Moscow (constructed); a design for the Lenin mausoleum; and a comprehensive project for the Dnieper River hydroelectric dam. Having devoted much of his career to designing mansions and commercial structures, Shekhtel no doubt welcomed the opportunity to use his talents for a broader segment of society; yet he did not adopt the radical vision of Constructivism—unlike Aleksei Shchusev, who skillfully applied the Constructivist aesthetic until it too went out of favor. As he had done before the revolution, Shekhtel employed a functional or a retrospective approach, according to the purpose of a given project.[86]

In addition to his administrative and design work, Shekhtel continued to teach at the Stroganov School, reorganized in 1920 as Vkhutemas. His affiliation with the school dated from 1896, and it was there, in 1919, that he delivered to a group of students his only surviving pronouncement on architectural aesthetics. The lecture, "A Tale of Three Sisters: Painting, Architecture, Sculpture," surveyed architecture as a synthesis of the arts and defended Shekhtel's own work in the style moderne.[87] Though brief, it is a valuable commentary on what he considered his major accomplishments. The reference in his title to the muses as three sisters, undoubtedly an homage to Chekhov, also reminds one of the classical panel above the entrance to his house on Bolshaia Sadovaia.

After reaffirming the fundamental role of "work, love, and art" in life, Shekhtel noted the importance of painting and sculpture to great works of architecture, from the dawn of civilization through the flourishing of Egyptian, Greek, Islamic, Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance architecture. In this survey of architecture as an evolving, unified tradition, Shekhtel illuminates aspects of his own work, such as color and rhythm in the definition of structure. For example, his comments on the Islamic monuments of Central Asia can be seen within the context of his own use of polychromatic designs on the Riabushinskii house.[88]

That Shekhtel also appreciated the genius of Russian architecture—particularly in medieval Novgorod and Moscow—suggests a closer, native, source for his synthesis of architecture and the decorative arts: "Russian architecture from the very beginning of its independent existence proceeds inextricably with painting."[89] With this statement he turned to his own time and work, emphasizing his relation to Vrubel and to Viktor Borisov-Musatov. He juxtaposed the monumental wall paintings in Kiev and Nizhni Novgorod by Vrubel with the

painter's work at various houses by Shekhtel (including two for the Morozov family). As for the Derozhinskaia house: "Borisov-Musatov began a cycle of romantic panels from reminiscences of the 1840s, but his premature death prevented him from finishing them."[90]

Shekhtel's retrospection concluded with what he justifiably considered one of the high points of his career: the pavilions at Glasgow. He recounted proudly their synthesis of art and architecture and their exemplary combination of traditional Russian forms and materials with the style moderne aesthetic:

I remember with great pleasure the collaborative work of painting the churches I built and [of painting] the pavilions of the Russian section at the International Exposition in Glasgow . . . with my former students from the Stroganov. This small community brilliantly fulfilled its task, and the stern British loudly cheered the color of these wall paintings. . . . The building of the Russian section was carried out by a group of two hundred Russian workers, whom I sent by sea to England, and [the buildings] were of Russian timber exported from Arkhangelsk.[91]

One wonders how this vade mecum was received by his students in revolutionary Moscow, with their ideals of radical transformation in the arts; but it is characteristic of Shekhtel that he acknowledged generously his debt to an earlier group of students, just as he fulfilled his professional responsibilities toward a new generation. And he was by no means unaware of theoretical insights associated with the use of color in modern art: his final comments on the properties of color in enhancing or modifying the perception of space could be related to work by Vasily Kandinsky, as well as other contemporary artists.[92] Nonetheless, postrevolutionary criticism was not sympathetic to the aesthetic principles Shekhtel had maintained.[93]

Russian critics acclaimed Shekhtel's work—even when he was at the height of his creativity—less than that of his contemporaries in Central Europe. In this light it is revealing to examine an extensive commentary on his work by Vasilii Kurbatov—one of the few to appear during Shekhtel's lifetime. Kurbatov, surveying architecture since 1900, placed Shekhtel in the front ranks of Russian architects, but always with reservations:

Of much greater importance is the striving for simplicity and rationality. English architects have succeeded at this, as have Germans such as Olbrich, Hoffmann, et al. Among the Russians, Shekhtel approached such a resolution, but not once did he succeed in carrying it through to the end: all of his buildings are brilliantly conceived, technically superb, but none achieves a culmination. The buildings at the exposition in Glasgow are decorative, but they do not have the poetry of Korovin's village [at the 1900 Paris Exposition]. The church in Samara Province skillfully resolves the problem of a tent roof over a large space, but all the same it lacks poetry. Perhaps because of the stunning variousness of his talent he could not perfect any of the building types.[94]

Kurbatov's comments were often perceptive, but a critique derived from a subjective notion of "poetry" could hardly do justice to Shekhtel's fusion of aetheticism and modernity, which expressed the vitality of a transitional age rife with contradiction. The new economic and social forces of this period demanded a large-scale application of functionalism to modern building technology while other forces—romantic, retrospective, or simply reactionary—encouraged a return to picturesque, colorful, anachronistic forms. Shekhtel explored each of these trends with rare fluency, yet his work is never limited by them. The manifold nature of Shekhtel's creativity is in fact the great strength of this architect, as it was of contemporaries such as Josef Hoffmann.

At the same time, Shekhtel cannot reasonably be considered one of the leading innovators in modern European architecture. There is, perhaps, a comparison to be made between the Riabushinskii brothers' fruitless search for an ideology to support their vision of the future and Shekhtel's limited means for designing and building in this century. Although the style moderne provided a necessary antidote to the stylistic welter of the late nineteenth century, it was transitory, quickly superseded throughout Europe. Shekhtel seems to have understood this, but he advanced no other vision of architecture and society in the modern age—nor was he particularly concerned to do so. His sense of architecture as the design of aesthetic objects remained a constant, whatever he chose to create. He lived to see his architectural values discarded; yet it is unlikely that as an architect at the end of a successful career he would have minded, knowing as he did that most styles are the product of their age.