Preferred Citation: Witkin, Zara. An American Engineer in Stalin's Russia: The Memoirs of Zara Witkin, 1932-1934. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft18700465/

| An American Engineer in Stalin's RussiaThe Memoirs of Zara Witkin, 1932–1934Edited with an Introduction by |

Preferred Citation: Witkin, Zara. An American Engineer in Stalin's Russia: The Memoirs of Zara Witkin, 1932-1934. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft18700465/

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the following for their contributions to this volume: Victoria Bonnell of the Sociology Department of the University of California at Berkeley, Sheila Levine of the University of California Press, and Elena Danielson of the Hoover Institution Archives, for their early and unflagging support for the project; Kenneth Patsel, Galina Aleksandrova, and Svetlana Afanaseva, for obtaining Emma Tsesarskaia's original consent for an interview; Liudmila Budiak and Tatiana Krylova of the All-Union Research Institute of Cinema Art in Moscow for their help in locating Tsesarskaia and arranging the interview; Holland Hunter, emeritus of the Economics Department of Haverford College, for his evaluation of Witkin's statistical work on the five-year plans; Peter Kenez of the University of California at Santa Cruz, for his expertise; Jeffrey Pott, for providing photographs of Witkin's buildings (one of which now serves as headquarters for the Church of Scientology and discharges suspicious and unpleasant chaperones to intimidate photographers); Bernard Witkin, for sharing information about his brother; the research staff of the library at Franklin and Marshall College, for answering scores of questions; Dore Brown of the University of California Press, for her painstaking and creative copyediting; and most important, Emma Tsesarskaia herself, for the kindness and generosity she showed by meeting me. At various stages of the preparation of this volume I benefited from the generous support provided by a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Center for Slavic and East European Studies at the University of California at Berkeley; a short-term grant from the International Research Exchanges Board (IREX); and a summer research grant from Franklin and Marshall College.

A Note on the Text

This text was prepared from a copy of an original manuscript that resides in the archives of the Hoover Institution. It has been only lightly edited to correct obvious typographical, grammatical, and spelling errors. For purposes of clarity and consistency, the author's transliterations of Russian spellings have been modernized to conform to the Library of Congress system. Proper names have been edited for conventional American spelling. Where spellings have not become standardized, they have been left as Witkin spelled them; for example, names that today would end in "skii" remain "sky." Witkin's lover's name appears as "Tsesarskaia" in the introduction and notes but as "Cessarskaya" throughout the memoir itself. Witkin's translations and transcriptions of articles and letters are often approximate but have been allowed to stand. Many of his turns of phrase would not escape the editor's pencil today, but they have also been allowed to remain because they convey the charm of Witkin's innocent and idealistic personality. Endnotes and an annotated bibliography have been added to identify people and institutions now unfamiliar to most readers and to suggest further reading on subjects which figure in Witkin's memoir. Bracketed interpolations are mine.

Editor's Introduction

A chronicle of war and love, these memoirs tell the story of an American engineer's battle against the bureaucratic system that grew on the ruins of the Russian Revolution and matured under the iron rule of Joseph Stalin. They tell, too, of his dream of a better world, a dream that became personified in the woman he loved, the screen star Emma Tsesarskaia.

One of the most brilliant foreign engineers in the Soviet Union during the 1930s, Zara Witkin left for Russia in 1932, fired by the belief that a noble attempt to refashion human society was taking place there and intent on finding the woman who had come to symbolize for him the dignified and joyous race that would populate the socialist utopia now being built. In the course of his two-year stay he found, and then lost, Emma; and in his mission to help modernize Soviet construction methods he fought, and ultimately was defeated by, the red tape, cynicism, and venality that were strangling Soviet Russia more surely than the "capitalist encirclement" of which official propaganda warned. More than fifty years later, as the Soviet Union struggles to cast off the pall of Stalinism, publication of Witkin's memoirs is especially timely. His story sheds a penetrating light on the sources of the bureaucratic cancers that spread during decades of political and economic centralization and now threaten the stability of the Soviet state.

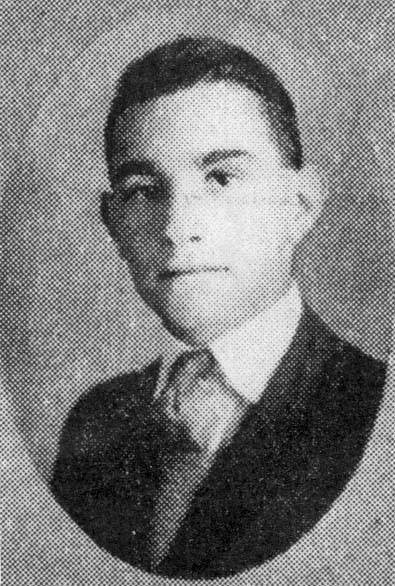

Though only thirty-one years old when he went to Russia, Witkin had already proved something of an engineering genius. Born in 1900 to a family of Jewish emigrants from Russia (his last name is an Americanized form of the Russian Utkin ), Witkin attended a polytechnic high school and entered the University of California in 1917, at the age of sixteen. He graduated with honors from the College of Civil Engineering at twenty and was elected valedictorian of his class. At fifteen he had already designed and manufactured calculating machines for the Patented Computing Company, and by the time he received his bachelor's degree he had worked as reclamation engineer for the state government,

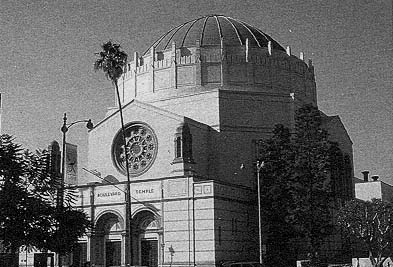

maintenance-of-way engineer for Southern Pacific, and engineer for the San Francisco Bureau of Governmental Research. He designed the Curran Theater in San Francisco in 1921. Beginning in 1923 he served as chief engineer of a major construction firm in Los Angeles, where he supervised construction of scores of edifices, including the Hollywood Bowl and the Wilshire Temple. Not long after his return from the USSR in 1934, he founded his own firm manufacturing prefabricated housing components.

Witkin was exceptional among professional builders for his lifelong concern with justice and political change. His given name appears to be an anglicized form of the Russian zaria , or dawn, perhaps reflecting his parents' faith in the forthcoming dawn of a new era. His relatives shed their blood in the Russian Civil War, and the events of the Revolution had an electrifying effect on his family in America. Zara began to follow Soviet affairs with interest and sympathy in his teens. The Great Depression following the stock market crash of 1929 did more to persuade Witkin of the bankruptcy of capitalist civilization than any Soviet propaganda, while the initiation of a planned economy in the USSR in 1928 convinced him that this was the most promising experiment in human history, the creation of a society run not for profit but for human needs, a society based not on the anarchic laws of the market but on the rational satisfaction of the interests of the entire population. The Five-Year Plan offered grandiose horizons of planned economic growth for the benefit of all, a scheme tailor-made to capture the imagination not only of idealists but also of pragmatic engineers.

A physically vigorous man—he was a respectable tennis player and a serious amateur boxer—Witkin was also a sensitive and accomplished pianist who disdained the money-grubbing rough-and-tumble of the American construction industry. The more successful and prosperous Witkin became, the more he worried about the future of the world, and the more repelled he was by the irrationalities of a capitalism under which production benefited the few and left millions in poverty. He came to consider himself a socialist. A friend later wrote that he brushed off negative reports on Soviet conditions as "capitalist malice" and avidly accepted "every panegyric that gave color to his hope."[1] One day after an address before an engineering society on the Five-Year Plan, Witkin was approached by Alfred Zaidner of Amtorg, the Soviet American Trading Company. He was persuaded to establish collaborative business contacts, including consultation on the development of refrigerated warehouses,

assistance in the sale of Soviet marble in the United States, and selection of engineers to work on the construction of the Moscow metro.

He had already decided in principle to take his skills to the Soviet Union when he began to attend Soviet film showings. At a 1929 screening of Village of Sin (originally Baby riazanskie , or Peasant Women of Riazan ) he first beheld the lovely, dark-haired Emma Tsesarskaia. He later wrote that when she appeared on the screen he involuntarily jumped out of his seat. Tsesarskaia became the embodiment of the new Soviet womanhood for him—independent, emancipated, proud. In the film Her Way of Love the full-figured beauty again played a peasant woman liberated by communism, strong and defiant, taking up arms to defend the Revolution. Witkin became obsessed with her, returning to watch the film eight times. Slowly he convinced himself not only that his future lay in the Soviet Union but that somehow destiny would one day join him and Emma. Little could he imagine how this would happen, still less what heartbreak awaited him in the land of his dreams.

Eugene Lyons (1898–1985), the Moscow correspondent for United Press International between 1928 and 1934, was also destined to play an important role in Witkin's Soviet experience. Lyons was famous before his arrival in Moscow for his defense of Sacco and Vanzetti[2] and was well known as a fellow traveler of the Communist party. His years in the "workers' paradise" were slowly transforming him into a bitter critic of the Soviet experiment, and the journalist would one day leave a scathing account in his memoir, Assignment in Utopia .[3] After the war he emerged as a prominent cold warrior.

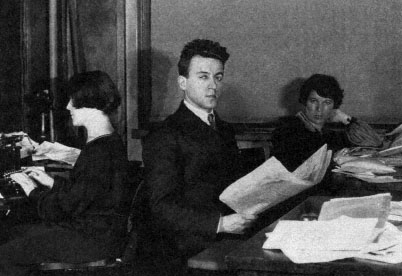

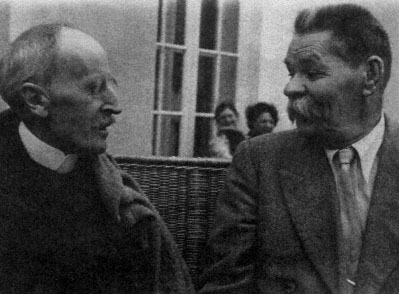

Before Witkin left the United States (he went with a one-month tour group and began talks with prospective employers only after arriving in Moscow) friends had written a letter of introduction to Lyons, and after settling into his new career, Witkin paid his first call. The two soon became fast friends, and it was through the agency of Lyons's wife, who played small roles in the Soviet movies, that Emma and Zara were later acquainted. Lyons left the following portrait of the idealistic young engineer who arrived in Moscow in 1932.

A dark, chunky, broad-shouldered young man with an infectious smile and tanned open features, Zara came to the United Press office in Moscow one day in the Spring of 1932 to present a letter of introduction. Methodically, and rather to my amusement, he produced a bulky scrap-

book and proceeded to back up the letter with a sort of documented lecture of self-introduction.

He pointed to some of the scores of structures on the West Coast on which he had been chief construction engineer: the Hollywood Bowl, movie studios, hotels, churches. Here were examples of his professional writings in engineering journals, and here materials on his pioneer work on prefabricated housing. For contrast there were press items about a piano recital he had given, about athletic laurels he had won. Not in the least boastful—just informative, in precise and pedagogical style.[4]

In an interview granted in 1989, Emma Tsesarskaia confirmed the spirit of Lyons's impression. Witkin was not handsome, she told me, but he had a great force of personality and magnetic charm. He was "loyal to an extreme." Of medium height and athletic build, he had a vibrant sense of humor and "knew how to walk on his hands." Tsesarskaia recalled their weekly ski trips in the environs of Moscow and characterized Witkin as a man with whom it was a pleasure to spend time, a "cultured" person, at once American and European.

On another level, however, Witkin was a sober personality. Lyons had noticed a difference between Witkin and "the high-minded Americans come to exult in 'the great experiment.' ... Here was idealism armed with a slide-rule, open-eyed, and calm to the point of pedantry.... It would be interesting to watch how far this man got with the technical education of Russian builders."[5]

Witkin was but one of tens of thousands of foreigners who came to live in the Soviet Union before the war.[6] In the 1920s most were revolutionaries and political emigrants, but in the 1930s increasing numbers of technical specialists, skilled workers, and businessmen arrived, accompanied by journalists, diplomats, and an impressive flow of tourists and adventurers. Their impressions after they arrived were often determined by their political convictions before they left home. But powerful Soviet realities often overrode preconceived notions.

Those who broke out of the cycle of Intourist hotels and guided tours found a country in the throes of tumultuous changes: cities springing up where none had existed before; colossal factories rising from a sea of Siberian mud; teeming crowds of former peasants jamming the trolley lines of Moscow, Leningrad, and Kharkov, straining the resources of overburdened and underbudgeted housing funds, pressing their children into the proliferating night schools, technicums, and institutes. The

changes were not peaceful: millions were being uprooted from their accustomed ways under economic and political duress, many at the point of a gun. Hardly any perceptive visitor failed to see evidence of forced labor or to hear about the arrests of scapegoats accused of economic sabotage, pragmatists who had cautioned against breakneck industrial expansion, and oppositionists who had resisted Stalin's dictatorship. Others reported hordes of homeless children—refugees from the violence and famine that attended the collectivization of agriculture—begging in the train stations or roving in large gangs of pickpockets, thieves, and underage prostitutes. At the same time, few remained unimpressed by the very scale of change, by the rapid promotion of education for the masses, and by the widespread sense that the current sacrifices were the necessary price of a more just and prosperous future.

Sojourners in "the first socialist society" produced a great literature of firsthand accounts, including travelogues, memoirs, and journalistic reports. Though many of these are superficial, either naively pro-Soviet or simplistically anti-Soviet, others are of great interest, describing the experiences of people whose business took them to many parts of the country. The best examples of this literature are by foreigners who resided in the USSR for an extended period, especially those who became integrated into the local life. Many among the latter group were Communists or sympathizers, and although they often colored their records accordingly, in some cases it was precisely they who most keenly appreciated the evils people encountered, and who produced—often after painful periods of tortured soul-searching—some of the most incisive accounts of Soviet reality.

A number of those who served as workers and technicians in Soviet industry recorded their experience in memoirs. John Scott's classic, Behind the Urals: An American Worker in Russia's City of Steel ,[7] deservedly the best known of the genre, recounts the author's life in the frontier boomtown of Magnitogorsk. Scott was a sympathizer who, out of loyalty to the cause, suppressed much of his own experience in the book, but the 1989 edition includes long-unpublished material on forced labor and the secret police. Andrew and Maria Smith's I Was a Soviet Worker also deserves mention,[8] and though the authors spent less time in Moscow, where Andrew worked at an electronics factory, than Scott spent in Magnitogorsk, their book is more uncompromising in its portrayal of political relations inside a Soviet enterprise. Fred Beal, an American labor organizer who skipped bail after his conviction in the

notorious Gastonia Boys trial and worked for two years at the Kharkov Tractor Factory, left another valuable account of industrial life in the early 1930s in his Proletarian Journey .[9] Peter Francis's I Worked in a Soviet Factory , the sympathetic but objective record of a British student employed in a plastics factory in Orekhovo-Zuevo, is also of interest, though it is not as penetrating as the previously mentioned works.[10]

The literature left by engineers and specialists constitutes a greater mass than that by workers, but it is generally of a lower quality (the workers more often came to live, the engineers to make money and leave). The memoirs of John Westgarth (Russian Engineer ), who served as a consultant to the Soviet steel industry, are poorly written and not particularly informative. Working for the Soviets: An American Engineer in Russia by Arnold Rukeyser,[11] who worked for the Soviet asbestos trust, and Moscow, 1911–1933 by Allan Monkhouse (a British defendant in the Metro-Vickers show trial of 1933)[12] are somewhat more interesting, though also colorless and politically unsophisticated. While none of these engineers was taken in by the system of propaganda and controls calculated to veil Stalinist realities (others were more gullible),[13] none succeeded in penetrating the barriers isolating the foreigner from participation in Soviet society. Somewhat better is John Littlepage's In Search of Soviet Gold , which describes the authors' ten years in the mining industry of Siberia, Central Asia, and the Urals. Littlepage's book not only draws the reader into the daily difficulties and accomplishments of the Soviet industrialization drive but also captures much of the color of the country's frontier regions. Despite these insights, it reflects little understanding of Soviet industrial politics. A politically innocent pragmatist, Littlepage failed to pierce the smokescreen obscuring behind-the-scenes Russia. The arrest and liquidation in 1937 of his superior in the gold trust, A. E. Serebrovskii, a man for whom he felt no small admiration (and who also left a memoir of genuine value), caught him quite unawares.[14]

Against this background Zara Witkin's memoir is a welcome—indeed marvelous—exception, comparable with or superior to the best of the memoirs officially published in the Soviet Union (S. Frankfurt's Men and Steel , for example).[15] The only other memoir to which one could properly compare it is the émigré Victor Kravchenko's classic, I Chose Freedom: The Personal and Political Life of a Soviet Official ,[16] which details the authors' experiences in heavy industry from technical school to Moscow commissariat. For Witkin found himself a part not only of the inner workings of Soviet industrial administration but also of internal industrial politics . And, unlike any of his foreign colleagues, he

created a paper trail recording every step of his career and every battle of the war in which he soon became engaged.

Reading about Witkin's experience sometimes gives one the impression of having a ringside seat at a boxing match. Lyons later recalled how "the very sight of this calm, business-like American engineer gave the bureaucrats the jitters." Witkin became Lyons's champion in the latter's effort to build a cooperative apartment. Manipulated, stalled, deceived, and robbed for years, Lyons had floundered "in the practiced hands of the cooperative bureaucrats." But Witkin, touched by the journalist's "gullible helplessness," took command of the situation.

While engaged upon rationalizing construction activities for the entire Soviet Union, or supervising the construction of a great aviation school or chemical plant, he made the time to inspect the Lyons home in progress. No trick of faking in materials or workmanship escaped his trained eye. Bolder, more pugnacious, and more optimistic than I, Zara made this apartment a test case of rationalization and honesty in construction. He forced the builders to tear down walls that were ill made, watched the mixing of paints, insisted on elementary principles of decent workmanship.... He would listen to a long harangue of pyramided alibis, pretend that he did not understand a word, and remark coolly, "Khorosho! [All right!]. Now tear up this floor and do it right!"[17]

Not long after the engineer settled down to teach the Soviets the technology of prefabricated construction he came up against the pervasive lethargy, incompetence, and outright corruption of Soviet industrial administrators. Talented, energetic, and selfless, Witkin did not fit in. He produced a number of significant innovations in construction technology that saved the Soviet Union millions of rubles and, at a time when it was straining every resource to industrialize, could have saved it hundreds of millions had the socialist system encouraged innovation and enterprise. But his efforts aroused the jealousy of the officials, who saw in him a dangerous adversary who might expose their own inefficiency. The story of Witkin's design for interlocking blocks—less expensive to manufacture, stronger, more heat-retentive, and more stable in unreinforced walls than those then in use—runs through several chapters, and indeed its impact colored much of the author's experience in Russia. Stalled by indifferent bureaucrats, very nearly robbed by Soviet engineers eager to plagiarize his work, the victim of subterfuge, duplicity, laziness, venality, jealousy, and stupidity, Witkin turned to other forces more eager to free the country from its bureaucratic quagmire.

This ordeal forms another unique facet of the author's memoir. For no other foreigner worked as closely with Soviet regulatory and investigatory agencies as Witkin did. Lyons recalled that more than anything else, the interlocking blocks episode was what set Witkin on the warpath. The correspondent had a hand in the events:

Zara was in no mood for compromise. One day I decided to enlist the interest of a prominent Soviet journalist, a brilliant communist named Garri. Garri liked few things better than to smoke out bureaucratic chairwarmers. This case was exactly to his taste. For many days he conferred with Zara, ending up even more indignant than Zara or the U. P. correspondent.

Under Garri's guidance, Zara wrote a letter to Stalin; he cited names, dates, places, documents. I helped edit the letter—it was not a complaint but a matter-of-fact record. Garri undertook to deliver this to Stalin and informed us a few days later that he had done so. Soon a long and vitriolic article by Garri appeared in Izvestiia , in which the American's experience with the building block was the peg for an attack on the offending organizations.

Instantly things began to happen. The whole atmosphere in Soiuzstroi , where Zara was employed, changed. Lost papers were found; conferences were called to consider their contents; the Leningrad trust [the "graveyard of thousands of ideas" to which Muscovite incompetents had dispatched Witkin's reports] hastily recognized that it had made a mistake and essential documents were rushed to Moscow by airplane! Gratifying as it was to see the somnolent bureaucratic monster suddenly awake, the sight was both ludicrous and pathetic. The pervasive indifference had merely been replaced by pervasive fear. Everybody rushed in pitiful panic to make amends. They had heard the crack of the whip....

At last, at last, Zara thought, he would be able to deliver the gift he had brought from California. He would teach Soviet Russia the ABC of modern building! He had the love of Emma. He had the chance to work. It was assumed that Stalin was watching from his Kremlin. Soiuzstroi called on Zara to draw up a detailed plan for rationalizing construction for the entire country, and the war seemed won.

But all of us—Zara, Garri, Stalin—apparently were underestimating the strength of the entrenched bureaucracy, with its stake in the prevailing methods. For two months or so fear agitated the surface of the various departments. Then there was a gradual decline of fervor and everyone slid back into his accustomed groove. Garri was off fighting other and no less important fights. Stalin perhaps considered this problem solved. Once more the American engineer was bruising his forehead against solid walls of habit and hostility. The plans everyone praised were gathering dust; essays he wrote on order remained unpublished. Buildings collapsed precisely as he had warned they would unless preventive measures were taken. He was approximately where he had been at the start.[18]

The battle of the interlocking blocks—one is tempted to name it the battle of the interlocking blockheads—was only the beginning of the war. It came to the attention of important people that Witkin was not merely an engineer but a fighter, a potential heavy gun in the regime's own fight against the bureaucratic disease. Witkin was soon engaged by the powerful Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate—a sort of superministry of investigations responsible for routing corruption and incompetence in all state, party, and economic agencies—and was one of very few foreigners ever to work for that agency. He was possibly the only American to be engaged as an industrial expert by the secret police, the OGPU, for whom he carried out an unprecedented series of assignments at highly secret military construction sites, including an airplane factory, power plants, synthetic rubber factories, and an artificial silk factory. Lyons recalls him mercifully resisting OGPU demands to fix blame on individuals after investigations of delays and accidents: "It was not sabotage, he insisted, but sheer technical backwardness."[19]

His technical prowess earned him appointments to a variety of construction agencies. The memoir records his relations with the Commissariat of Heavy Industry, the Council of Labor and Defense, several trusts, and the Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate. It is possible that no other Western specialist had Witkin's level of contact.[20] One assignment was to a commission formulating construction targets for the Second Five-Year Plan (again, he was probably the only American ever to participate in the formulation of the plan), a role that gave him access to the true figures for new construction under the First Five-Year Plan and the projected figures for the second. Based on this work, Witkin spent seven months calculating the actual figures for construction under the First Five-Year Plan (as opposed to the inflated official figures). He arrived at two stunning conclusions: in no year of the plan did total construction exceed that in Imperial Russia for 1913/14; and total physical construction for the entire first-plan period was less than that in America for an average single year between 1923 and 1932. These conclusions were subsequently published in a series of articles for Engineering News-Record in August 1934. Not enjoying the benefit of the theoretical tools and greater information available to economists today, Witkin nonetheless produced a remarkably shrewd analysis.[21]

During his two years of work on housing projects, industrial enterprises, investigatory missions, and economic planning, Witkin made numerous contributions to Soviet construction practice. Most of these were

what we would call today "appropriate technology" solutions to problems of development in a capital-poor country: new methods for employing excavation equipment, a design for very wide span trusses, a new kind of crane, the exploitation of local materials in brick manufacture, a new process for manufacturing wallboard, standardized methods for production of building components, changes in the organization of labor and administration, and dozens of other innovations. Working with almost superhuman intensity, Witkin compressed as much industrial experience into his two years in Russia as many specialists did in far longer stays!

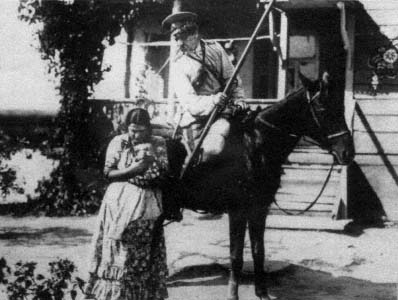

If Witkin's career in the USSR makes his memoir a valuable historical document, the story of his love for Emma Tsesarskaia lends the manuscript the warmth and romance that set it aside from accounts by other visitors. Emma was one of the most popular Soviet actresses of the late 1920s and 1930s. Eugene Lyons and his wife knew her well, for their apartment was a favorite gathering place for Moscow society. In the months before Witkin met Lyons and confided in him his hope to meet Emma, he nearly despaired, for though her picture was to be seen on billboards, in magazines, and in shop windows, she seemed even more remote in the Soviet Union than she had in America. However, through the Lyonses Witkin met an actress named Klavdia Mikhailovna, and when he saw her walking with Tsesarskaia on a Moscow street one day he stood gaping as if struck by lightning. But he recovered his senses quickly enough to greet Klavdia, who then introduced Emma. More than fifty years later Tsesarskaia still remembered the foolish grimace on Witkin's face. She was not especially pleased that he had bumped into them, for she was constantly hounded by fans, especially men, who would sometimes mob her on the street, in the theater, at train stations. Klavdia told Lyons that night, "your friend the engineer behaved as if he were seeing ghosts."[22] Fortunately for Witkin, Lyons's wife felt challenged and arranged a party to introduce the two under more favorable circumstances. Klavdia collaborated by inviting Emma. The party went off well, "none of the other guests suspecting," Lyons wrote, "that they were mere stage props for Cupid."[23]

It is easy to understand why Tsesarskaia was so popular. Critics at home and abroad spoke highly of her intelligent performances, both before and after sound.[24] She appeared in pictures from the age of sixteen (she was born in 1909), after a director of a documentary noticed her in some cuts and was so enchanted that he detailed agents to scour the

streets of Moscow until they found the girl. In 1928 she graduated from the Tchaikovsky Film School in Moscow, having already starred in Village of Sin , one of her most important films. Writing of her beauty many years later, Lyons stated that even the movies did not do justice to "the dark brown hair, the full red lips, the large, dark hazel eyes."[25] Oldtimers today wistfully recall her full figure, straight white teeth, and peasant vigor (one retired officer with whom I spoke hastily qualified his enthusiastic comments at a black glance from his wife). At one point Emma's mother threatened in desperation to move out from their apartment because the phone never ceased ringing, as fans, mostly male, tried to contact her. Emma herself admitted to me in 1989 that on some days she "felt afraid to look in the mirror because [she] was so beautiful." She was of mixed Jewish, Ukrainian, and Moldavian background, and her features suggested to a generation the wholesome beauty of a Russian village girl, the image directors O. Preobrazhenskaia and I. Pravov sought to convey in such films as Village of Sin and The Quiet Don (based on the novel by Mikhail Sholokhov, who fell in love with her during the filming). Tsesarskaia's convincing performance of the heroines in these and other films won her the title "Honored Actress" in 1935. All in all, Tsesarskaia appeared in eighteen films during her career, as well as in numerous theatrical roles at Moscow's Central Film Actors' Studio.

Emma had a personality to match her looks, "at once poised and mischievous," as Lyons recalled, exuding life and warmth."[26] The American writer Waldo Frank, who shortly before Witkin's arrival in Moscow visited Tsesarskaia at her home—a modest, one-room apartment for two, with an oil stove for a kitchen and an unpainted bookcase filled with the classics of Russian and world literature—described her as "a girl soberly devoted to her work, who accepts life as a hard place from which one wins experience, pain, joy, even ecstasy: not 'success.' Yet she is ambitious, she loves to be praised. But when she shows you the 'stills' of her new picture, you think of a school girl rather than of a star, so simple is her anxiety for approval; and of an artist, so true is her standard of values."[27]

With Klavdia Mikhailovna interpreting during their first formal meeting at the Lyonses, it was arranged for Witkin and Tsesarskaia to exchange language lessons (Zara learned fast, Emma even more so, though she has forgotten English today). The story of the increasingly close friendship that grew from these lessons is recounted in these memoirs.

But Lyons bore independent witness to Witkin's account many years after his death: "It was pure joy to see Zara and his goddess together; he so solemn and protective, Emma gay and full of the devil. When the four of us were alone she liked to undo the heavy knot of hair on the nape of her neck and send the dark-brown torrent cascading to her knees."[28]

Before long Zara and Emma were discussing plans for marriage and eventual emigration to California. Lyons wrote that they occasionally involved him in their "earnest conferences." He sounded out his Hollywood connections through diplomatic pouch and raised some interest in featuring the Russian beauty in American films. Witkin wrote repeatedly that he drew strength for his work and his battles from Emma's inspiration, and he spoke of this as "a golden time." But in the late spring of 1933, Zara began to detect a note of anxiety in Emma's voice, subtle changes in her behavior. In Lyons's words,

Emma, until then so full of hopes and plans and mischief, seemed more and more melancholy, weighed down by secret worries. Suddenly she was afraid to be seen with Zara in public, reluctant to visit the Lyonses. Suddenly she talked of the trip to America, until then the cornerstone of their future together, as if it were only a pretty legend rather than a plan. To avoid worrying Zara, Emma Tsesarskaia pretended the old high-spirited gayety, but it now sounded hollow. Because his every effort to pierce her secret made her unhappy, he dared not press her too hard.[29]

It became ever more difficult to see Emma, or even to contact her by phone. Naturally Witkin and Lyons began to fear the worst—that the secret police were putting a damper on the plans of one of the country's most prominent personages to abandon the land of socialism for the capitalist world. Lyons confessed that he had never in his heart really believed that Emma would be allowed to leave. Emma began to plead that "her father" was adamantly opposed to all talk of emigration. Zara understood "father" to mean "OGPU." As his last rare contacts with Emma faded into the past, Zara lost his strength for the war against the bureaucrats and began to talk of returning to America.

At the same time, however, Witkin's value as an industrial troubleshooter had convinced the OGPU of the desirability of persuading him to stay in the USSR. In a series of meetings they offered the inducement of his choice of prestigious and high-paying jobs with sufficient authority to get things done. They tried to persuade him to bring his family and to accept Soviet citizenship (when this part of the memoir

was read to Tsesarskaia she stated that Witkin would surely have perished in the great purges had he accepted their suggestion). Almost despite themselves they showed their true spots. Hinting that cooperation would make relations with Emma easier, the OGPU tried to get Witkin to report on the political opinions of his friends among the foreign journalists and engineers. They were especially concerned with the German architect Ernst May, whose patience had been exhausted in the same kind of battles Witkin had had to fight, and who was preparing to leave Soviet Russia. Witkin exploded at their insolence, reminding them that he was a foreign national and not a Soviet citizen whom they could order about as they pleased. In a conversation with an American consular official in Warsaw (he renewed his passport there in December 1933) he reflected that his outburst might cause difficulties when he returned, and indeed this may partly explain his failure to obtain cooperation during his last attempts to continue work in January 1934.

Witkin had given up on reestablishing the relationship with his beloved Emma. After the futility of his plans to work had become apparent, he left the Soviet Union in February, defeated and brokenhearted. Not long before he left he met the lovely and vivacious pianist "M." at the Lyonses, and he seems nearly to have fallen in love once again: certainly "M." swore to meet him in Paris, promised to join her life to his, and offered to bear his children. Witkin understood that this could never be and left before suffering another tragic romance in Russia.

What did Emma Tsesarskaia have to say about these matters half a century later? I traveled to Moscow in the summer of 1989 to find out. It was not easy to trace her, nor to obtain the interview. She requested that the meeting take place under official auspices, and I was therefore accompanied on my visit by a representative of the All-Union Institute for the Scientific Study of the Film Arts, Tatiana Krylova, who helped to locate Tsesarskaia and took part in the interview. Tsesarskaia consented only to a one-hour meeting, and though she permitted this "hour" to expand into five, it was not possible to see her a second time. She was cordial, though, and in the best Russian tradition offered endless cups of tea while insisting that we eat yet one more candy. Her famous beauty remained, transformed by the years into a ruddy, grandmotherly warmth. Stills from her movies hung on the walls of her tastefully decorated apartment in a central Moscow neighborhood. Learning of the existence of Witkin's

memoirs so many years after the events they recount came as a great surprise to Tsesarskaia, and the passages we translated clearly flattered and moved her.

Tsesarskaia's version of events differed from Witkin's. She told me that although Witkin had been a dear friend, she had not been in love with him. Whereas Witkin spoke of 1932 as a "golden" time of his life, Tsesarskaia referred to it with gentle humor as "copper." Her inability to reciprocate Witkin's love had disturbed her, and she had sometimes wandered the empty streets at night, anguishing "like Emma Bovary" over love's failure. Lacking the strength to disenchant Zara, she had not spurned his talk of marriage; Zara took silence as consent. In May 1933 Tsesarskaia met and fell in love with the man she would marry, Maksim Stanislavskii. Her new relationship was what actually lay behind the change Witkin and Lyons had noticed, not police pressure. Neither of the two Americans ever learned of Maksim or of Emma's subsequent fate. (Indeed, before I made contact with Emma in early 1989 she knew nothing of Zara's life—and death—after his last letter in 1934. Had I arrived half a year later she would never have known of Witkin's memoirs, for she died early in 1990.)

One wonders whether Emma's love for Maksim, the passage of half a century, or other factors may have dimmed the memory of her feelings for Zara in 1932 and 1933. But even if she had been in love with him, there was reason enough to decide against his proposal. Her father was an old Bolshevik and strongly disapproved of all talk of moving to America. Emma was exceptionally close to her family and quailed at the idea of abandoning her brother, ailing with encephalitis. As she explained to me, Zara's promise to build her a villa in California had little attraction for an emancipated woman who was accustomed to rejecting gifts proffered by male admirers. And as a Soviet patriot, how could she have left her country for the mere material rewards of a career in Hollywood—if indeed that career were realized?

Unfortunately, Emma's patriotism availed her little during the terrible events to come. In 1937 the secret police, now renamed the NKVD, arrested and shot Maksim, leaving her alone with a year-old infant. As the "wife of an enemy of the people," she was banned from the movies and evicted from her apartment. She lived only on the earnings from the gradual sale of her possessions (her mother had to fulfill this task because Emma was too well known to sell her own goods on the street).

The following two years were terrible for her, but in 1939 someone

intervened on her behalf in the highest circles. An acquaintance hinted that a lawsuit against the studio that had fired her after Maksim's arrest might succeed. It did, and the settlement brought her a large sum in back pay. Tsesarskaia once again could appear in the movies, and in the last years before the war she starred in A Girl with Character, Make Noise, Little Town , and Bogdan Khmelnitskii . She never did learn the source of this change of fate, but she suspects that Polina Zhemchuzhina, the wife of People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, and a friend of Emma's mother, may have pressed her husband to obtain Tsesarskaia's partial rehabilitation (the stigma of "wife of an enemy of the people" was not formally lifted until Stanislavskii was fully, if posthumously, rehabilitated under Khrushchev).

Emma was evacuated to Central Asia during the war; during our interview she recalled with laughter an occasion when she was surrounded by an applauding crowd at a train station in Tashkent during transit. She continued her career after the war, appearing in five more movies between 1946 and 1964. When Stalin died in 1953, she admitted she "wept like everyone else," having grown accustomed to thinking of him "as a father." One of her girlfriends called her a ninny, asking how she could cry for him after all she had been through. But, in her words, "that's just how brainwashed we were [vot do togo has odurmanili ]." Still, as Tsesarskaia told me, her fate after Witkin's departure had given her good reason to rue the decision not to go to California. To this day she recalls Zara's last, prophetic, words: "Be careful, Emma!"

Tsesarskaia received one short letter from Witkin while he was still in Europe but heard nothing more of him after that. In 1937 the NKVD required Tsesarskaia's presence as witness during their midnight search of a neighbor's apartment; after that frightful experience she destroyed all correspondence from abroad, including Witkin's letter. No other mementos of their time together have survived.

After Witkin left the Soviet Union in February 1934, he and Lyons spent two months traveling through Europe, visiting Berlin, Vienna, Paris, Madrid.[30] The high point of their journey was a meeting with the French novelist and Nobel Prize laureate Romain Rolland in his self-imposed Swiss exile. Rolland was Europe's most prominent pacifist (he abandoned his pacifism during World War II) and a moral beacon for a generation. Witkin once told Tsesarskaia that he had come to Europe to meet two people: her and Romain Rolland. But Rolland, a fellow traveler

for whom the USSR represented a bastion against fascism, was unable or unwilling to comprehend Witkin's and Lyons's tales of state terror, economic chaos, and politically induced famine.[31] Rolland's obduracy was the final disillusionment for Witkin.[32]

Back at home, Witkin picked up his career where he had left it in 1931. Though as a builder he went from success to success, Witkin appears never to have achieved the happiness that seemed within his grasp in Russia. He published his study of construction during the First Five-Year Plan, and in numerous articles for technical journals he recorded his most remarkable engineering accomplishments after returning to America. In Who's Who from the late 1930s he listed tennis and swimming as his favorite activities and music, furniture, and automobile design as his hobbies. He continued to describe himself as a democrat and socialist and an article he wrote in late 1934 on the future of working-class housing in America reflects his continued (though moderated) skepticism about capitalism.[33] Witkin's brother informed me that, despite his belief in social reform, he eschewed all public life. He was married only briefly, but the union was unhappy, and he had no children.

In 1939, Witkin became vice president of the North American Film Corporation, a company whose founders included Horace Sproul, president of the University of California. The company's purpose was to produce and distribute educational films in which people who were famous for having shaped the moral consciousness of their generation would speak about themselves. Although letters of intent were signed with the philosopher Bertrand Russell, the American socialist leader Norman Thomas, the historian Charles Beard, and others, I could find no evidence that any films were actually produced. Interestingly, the Romain Rolland Archives at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris contain three letters written by Witkin between April and December of 1939 to secure the novelist and pacifist's agreement to make a film; regrettably, the Archives seem to have lost the responses known to have been written by Rolland to Witkin. In none of Witkin's letters does he refer to his earlier meeting with Rolland or to their correspondence in 1934; their tone remains businesslike, and except for the author's "warmest wishes" for Rolland's health, Witkin indicates no hint of personal friendship.[34]

Zara Witkin died in Los Angeles on 16 June 1940 after a long and painful illness. A business associate later wrote Lyons that "in the last few years, Zara [had] not been the same Witkin I knew before he went to Russia." Lyons had indeed been aware that "though it was not visible on

the surface, his magnificent physique and his robust spirit had been broken down. The Kremlin had conquered an American engineer and idealist."[35]

The survival of Witkin's memoirs is itself a remarkable story. The author probably started them after concluding his articles on the Five-Year Plan. He apparently finished a first version in late 1937, when Lyons made certain suggestions for its improvement, and completed the manuscript sometime after March 1938 (he mentions the trial and execution of Bukharin and other old Bolsheviks) but before the Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact of August 1939 (which he does not mention). Both he and Lyons tried and failed to find a publisher for them. Possibly the two were thwarted by the attitudes of Western intellectuals, who in those years turned a blind eye to the evils of Stalinism, dismissed critical reports as reactionary propaganda, and effectively boycotted anyone who bucked this self-satisfied consensus.[36] (Eugene Lyons, Fred Beal, Andrew Smith, John Westgarth, and others have described the difficulties they faced in finding publishers, and the intellectual blacklisting they suffered after being published.)[37] It may have been impossible for Witkin to get a hearing in the New York publishing world. Then again, perhaps the editors he and Lyons contacted failed to appreciate the value of his record or were put off by the wistful, romantic style into which the hardheaded engineer lapses when he writes of Emma, the "Beloved Companion," his "Dark Goddess."

Whatever the reason, after 1938 or 1939 the two copies of the manuscript lay yellowing and forgotten. Not long after his death, Witkin's family burned his papers, leaving only Lyons's photocopy. Sometime in the mid-1960s the economic historian Antony Sutton[38] was in the National Archives in Washington reading the reports of American engineers who had worked in the USSR when he came across a record of Witkin's discussion with the official he met at the American embassy in Warsaw in 1933. Sutton searched and found his articles on the Five-Year Plan, but learned that the author had died and his papers had been destroyed. He was advised to contact Eugene Lyons, who in 1967 gave him the aging manuscript, which had miraculously survived with no significant damage. Sutton subsequently deposited it in the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University, where I came across it in the spring of 1988. Only now will Witkin's story finally find the audience it deserves.[39]

The Memoirs of Zara Witkin

1932–1934

To Eugene Lyons, whose soul was fired by the

heroic struggle of the Russian people for liberty—

whose heart was racked by their suffering,

whose hospitable door was open to all,

whose mind went to the core of political and

human mysteries; profound observer,

humanitarian, friend.

Introduction

The dread shadow of war hangs over the world. At any moment annihilation may fall upon the inarticulate masses. Mankind is divided into armed camps, nation against nation, race against race, class against class. This complex array is the expression of conflicting interests, appetites, ambitions—but above all of irreconcilable social philosophies, Fascism and Communism. Temporary masters have dug up and inflamed every human hatred from the blood-encrusted burial grounds of history. In the impending conflicts humanity will be blasted to its roots and civilization itself will tremble in the balance.

Of the two social philosophies whose champions have seized absolute power in critical sections of the world, Communism is the more significant because it is related more integrally to the life and needs of the masses and because it is an extension of the age-old yearning for a juster and happier world. Communism has altered fundamentally the existing social structure, where Fascism retains capitalism and religion, perverting them to its own ends. Fascism negates and destroys modern culture, arts and education by medieval bigotry and suppression, where Communism—in intention at least—evolves a new culture on the ashes of the old. Fascism and Communism alike demand absolute surrender of the individual to an authoritarian state, which means submission to irresponsible dictators subject only to their own whims or phobias. But whereas Fascism regards this as its fixed way of life, Communism insists that the submission is temporary, for the duration of a transition period.

Naturally it is Communism which has aroused the greatest hopes, stimulated the highest aspirations and engendered the darkest fears and bitterest opposition. By its vehement supporters, its deadly foes and by thoughtful observers alike it is recognized as the greatest challenge of our epoch, socially, economically and culturally.

Comprehension of events in the U.S.S.R. is therefore of the gravest import. The searchlight of exact and impartial investigation is needed to pierce the clouds of ignorance, misrepresentation and hysterical fanati-

cism. Only in the crucible of critical analysis can the new society be tested for the residues of historical truth.

For many reasons the significant changes in the Soviet Union are extremely difficult to understand. Theory is confused with practice, professions are confounded with behavior, wishful thinking puts blinders on otherwise sincere students. The enormous country stretches from Poland to the Pacific Ocean and from the sub-tropical shores of the Black Sea to the frozen wastes of the Arctic Circle, embracing all varieties of climate, topography and geology. The variety of human beings and cultures is equally vast.

Americans may appreciate the complexity of the Soviet land better by recalling that our own country is only a fraction of the size of the U.S.S.R. With our diversity of races and stages of social development—the Negro, the "poor whites" of the South, the foreign-born settlements, the most modern urban sections and backward mountain folk—the difficulty of a simple summary of the United States is apparent. How much more difficult in the Soviet Union, much larger and with even greater internal disparities and contrasts.

The dark and terrible history of the peoples who compose the Soviet nation, so remote, shrouded in legend, marked by centuries of bloody oppression, is a profound source of misunderstandings. A knowledge of that fearful past and its heritage in the customs and psychology of today is required to grasp the present tumultuous events, many of which flow inevitably from the dark channels of that grim history.

Language itself is a serious barrier to comprehension of the Soviet enigma. Entirely distinct tongues and dialects, springing from diverse and unfamiliar directions, are spoken by the races inhabiting this gigantic land. If speech were untrammeled, it would be difficult enough to follow through the maze of languages. But the heavy hand of dictatorship strangles the normal speech, distorts it into evasions and subtle allusions beyond the mental compass of the ordinary Western observer. Real meaning is conveyed in accents and overtones.

Casual and incompetent observers, dominated by private prejudices, draw diametrically opposite conclusions from the same observations. In the U.S.S.R. the obvious is almost never true. Only a few commentators have lifted the curtain which obscures the underlying forces and trends; the rest have merely made the curtain more opaque. Professional newspaper correspondents, concerned with the event of the moment, have rarely clarified the baffling contradictions. Under the stultifying throttle

of censorship they are obliged to limit their investigation and their expression. Moreover, the vast social enterprises—industrialization of a great agrarian continent, changes in property concepts, etc.—are a complicated technological process with which few reporters are trained to cope. Failing to understand the forces, masses and quantities involved, their reports have often misled the outside world.

A striking instance was the exaggeration of the magnitude of the First Five Year Plan, which was continually reported as equalling decades of American industrialization and which echoed uncritically the fantastic claims of the Soviet leaders. This great mistake had the widest political influence. Only by a realistic understanding of that plan could they have found the secret of the Soviet Government's foreign policies and the explanation for the dreadful sufferings of the Russian people through shortage of food and goods and from the horrors of political tyranny.

Evaluation of a social order rests ultimately upon its effects on the human mind and spirit. These cannot be adequately conveyed by description; they must be experienced. It is necessary to participate in that society's constructive life and to share its hardships. Only by tasting the suffering can the motivating aspirations and the driving forces beneath the surface be apprehended. This is the unavoidable task of the sincere student of a new society.

When a new order emerges from the seething cauldron of history, it is first approached in the light of its political characteristics. Underlying these outward forms, however, is its technological foundation, which vitally affects its policies and determines the conditions of its survival.

This has been especially evident in the Soviet Union. War Communism was called forth by the industrial breakdown of corrupt and incompetent Czarism. The New Economic Policy in turn was wrung from the Communist leadership by the necessity of stimulating production until a socialist program could be set into motion effectively. The First Five Year Plan, encompassing the four-fold objective of national defense, self-sustaining heavy industry, collectivization of agriculture and the education of the masses, was entirely dependent on the available industrial base and the solution of the problem of production.[1]

This problem of production was at the very heart of the Soviet situation. The terrible penalties imposed by the Soviet State upon its people for minor property offenses were the direct consequence of the breakdowns in production. Mass exile of millions of peasants, starvation inflicted upon

entire regions, "trials" openly and behind closed doors which sent thousands to death and hundreds of thousands to forced labor camps—all of these were desperate measures to spur critically failing production. Solution of the problem of production would have minimized such horrors of suppression and punishment and state slavery, which have disfigured the Soviet Union before the world and put the very philosophy of Communism in jeopardy.

The dream of creating a happier world was the impelling urge which drove me to participate in the vast reconstruction of the shattered country. A new life was to be reared, more beautiful, more comradely, more safe than mankind had yet known. That dream touched me in my boyhood. It seemed to me bodied forth in reality when the Bolshevik Revolution came in my young manhood. My love of construction, a certain natural talent for exactitude, made engineering my chosen career and I was fortunate enough to advance far on that road at an early age.

And it was precisely the engineering and construction aspects of the Soviet undertaking which fired my imagination. The abstract dream had become a problem in building and I felt that I therefore had a special contribution to make. The idea of going to the U.S.S.R. and donating such powers as I possessed was in mind at an early stage in the Revolution, and it acquired a more tenacious hold on me with the announcement of the Five Year Plan early in 1929. Instead of vague enthusiasm, I felt prepared to bring a concrete service to the common task—it seemed to me the task not alone of the Russians but of humanity.

Later the heroic beauty of a Russian woman came to symbolize that dream for me. She seemed to me the incarnation of the splendor and creative life of the revolution. The story of my love for this woman is woven into this chronicle, and it has, indeed, a profound relation to the entire Soviet scene: in it were mirrored the best and the most sinister elements of Soviet life. But it was only the symbol. The substance was the socialist future, the anticipated fraternity in labor, the new social order in the making.

My experience in Russia was essentially a struggle against the Soviet bureaucracy. I found that the release of the creative power of the Russian people was dammed by a wall of administrative bureaucracy, forced by its very nature to attempt the obliteration of the individual. This was the antithesis of the best principles of efficient engineering administration, and in the U.S.S.R. it destroyed the essence of responsibility in control. Few observers could penetrate beneath the dissembling surface of official-

dom to watch the grim combat between individual constructors and the entrenched bureaucracy—my chronicle, I trust, will give the reader some appreciation of this gargantuan struggle. In my own share in this struggle, just one episode in a great drama, my love for that Russian woman was a sustaining influence.

My two-years' assault on the ramparts of bureaucracy became, through a series of circumstances, an epitome of the larger struggle—almost a classic example of the problem involved. Ultimately the official press, and Stalin himself, took a hand in the complicated events. In a strange land, under foul living and working conditions, surrounded by deadly inertia, the unequal fight of one foreign engineer against a system of administration was carried on. Suspicion and misrepresentation, procrastination and distortion of plans, theft of ideas freely offered did not stop me. Indifferent to material rewards, careless of health, answering only the call of my conscience and my creative social urge, I persevered. But I deserve no special credit. I was one of many, Russians and foreigners.

The sombre saga of the creators pitted against a bureaucratic State has not yet been sung. If this book sounds the motif in that great dissonant symphony of Soviet life it will help to bring a little order out of the confusions around the Soviet experiment. It will help others to distinguish between the Communist ideal and its perversions in practice. Unless the Soviet lessons are learned, the investment of life, energy and idealism will have been a waste. The interests of the Communist dream itself call for open-eyed understanding and those who would obscure the truth are enemies of the dream, no matter what political labels they may wear.

I

The Russian Revolution of 1917 exploded a world weltering in agony and altered forever the course of human society. Far away, on another continent, in San Francisco, California, those fateful events stirred me vitally. Our home was one in which social conditions were constantly discussed. With sympathy and horror I watched the terrible struggles of the Russian people beset by civil war, foreign intervention, industrial chaos, paralyzed transport, plague and starvation. Their heroic endurance evoked my admiration. During the tremendous birth of the Soviet Union, I entered the University of California at Berkeley. Superpatriotism and provincial bigotry, the poisoned fruits of the war, permeated academic halls as they did the nation. War-time hysteria had run a frightful course. Monstrous penalties were imposed upon those whose humane scepticism questioned the cynical official aims of the conflict.

After the thunder of the battlefields came the terrible mockery of the peace. The false idealism, for which so much blood had been uselessly spilled, was revoltingly revealed. Still lower depths of misery awaited the helpless, disillusioned masses.

The post-war defeat of liberalism in the United States and the ensuing corrupt, anti-social governmental administration hastened the degeneration of an already infected economic order. I came to know the brutal injustices and waste, as well as the wonderful productive capacity, of American capitalism. No academic idea, this knowledge was the result of my continuous work in civil engineering, begun at the age of fourteen.

Concurrent with the years of education went work in civil, mechanical, railroad, structural and municipal engineering, giving me a broad acquaintance with the wolfish competition of industry and commerce which cared nothing for the betterment of human life, looking solely to its profits.

In 1923 I entered the construction industry: the very heart-beat of the nation's growth. The ebb and flow of building work, its unwholesome financial organization and perversion by predatory capital, were

indicators to me of the flaws in the nation's economic machine, destined to collapse after a holiday of optimism and speculation.

Warnings of the approaching danger met with violent, irrational responses, deepening my conviction of the fundamental necessity for social reorganization. With others, awakened to the threatening catastrophe, my eyes were increasingly turned to the vast Soviet socio-economic plans for the control of an entire nation.

In this period, I addressed an engineering society on the Russian Fifteen Year Plan, the general program of national development that was to include the First, Second, and Third Five Year Plans. On this occasion I met the manager of the Amtorg Trading Corporation,[2] the commercial agency of the Soviet Government.

Some days later, this official requested me to act as technical consultant to Amtorg. In this capacity I assisted in the selection of qualified construction engineers for the Moscow subway and in the repackaging and distribution of Soviet candy and caviar, which were imported in bulk. I also arranged for the use of some Soviet granite in our building industry. Finally, I prepared a comprehensive program for the construction of cold-storage warehouses throughout the U.S.S.R. The Amtorg manager frequently discussed with me the enormous potentialities of applying in the U.S.S.R. methods of pre-fabricated housing which our organization had developed.

The vast panorama of Soviet engineering possibilities unfolded before my eyes. I saw its far-reaching significance. For the first time in history a great nation was rationally remolding itself. The Soviet Union planned to reconstruct human society. A nobler human life was to be developed on a vast new technological foundation.

Engineers were vitally needed. Their creative powers, perverted by the crass exploitation of capitalism, were to be used for the benefit of society. This great call to the socially minded technical brotherhood of the world rang in my soul, a challenge to the best energies of mind and imagination. Never before had such illimitable horizons opened to engineers. Spiritual and social elements of such work would, I felt, surpass any material compensation. My decision was made to participate in it. If it fulfilled my anticipations, I proposed to bring over a staff of the ablest of my technical colleagues, who could make untold contributions to the new life.

Meanwhile an incident occurred of great personal importance which spurred my plans. In Los Angeles, at the end of 1929, a series of excep-

tional foreign moving pictures were shown. Several were from Soviet Russia.

The sincerity and depth of the portrayals, their historical significance and the brilliant realistic photography under the direction of Eisenstein, Pudovkin[3] and others, impressed me profoundly. They showed strikingly the tremendous possibilities of the moving picture in the cultural life of a people, when removed from the commercial sphere.

One night I went with my sister to see one of these Soviet films. We waited impatiently through the preliminary part of the program. Suddenly the great organ rolled out the poignant chords of Tchaikovsky's Symphonie Pathétique and the screen flashed forth the rising sun of the Amkino [Soviet-American Film Company] announcement—a Soviet film called Her Way . A fleeting moment for listing of the cast, author and direction, and the drama opened. A pre-revolutionary wedding scene. The swinging censer of the priest, the chanting choir, the excited young girls in attendance, the handsome, brutal face of the bridegroom. The lowered head of the bride. A doleful shaking of heads among the old women. They whisper that the groom had beaten his last wife to death. The swift searching glance of the bride in the direction of the whisper.

As the bride raised her head, I rose involuntarily from my seat, possessed spontaneously by the deepest emotions. My sister in wonder grasped my hand and looked inquiringly at me. I found no words to convey my thoughts. In that dark, beautiful face on the screen, I had read some deep, instinctive riddle of my own destiny. I felt a singular, irresistible force emanating from that lovely countenance.

The film proceeded to unfold a drama of heroic power. At the marriage feast, the groom surreptitiously strikes the bride in resentment at her refusal to accept the drunken attentions of his brother officer. Immediately she leaves the banquet-room. Her infuriated husband rushes out after her. Down the village street she strides, he following. She passes through her gate and swings it shut behind her. The maddened husband kicks it off its hinges and stamps into the house. He seizes a vase and dashes it to the floor in wild anger. Glancing over her shoulder she slowly draws the marriage hood from her head. Then turning towards him, she approaches. Her terrible eyes hold and quench the fury in his. Suddenly she strikes him a powerful blow in the face.

War! Mobilized peasants, in ill-fitting uniforms, stand, sombre resignation on their faces. Their women cling to them, weeping. Children look on wonderingly. Alone, rocklike, she stands while her officer-husband awk-

wardly approaches her for the farewell kiss, which she receives on the forehead without response.

The old, the young and the women carry on in the village. There is much work to do on her farm; plowing, sowing, carding, spinning. Determinedly she does this alone, sometimes, in utter weariness, after the day's task, sinking to the ground.

Winter passes. Spring comes. Spring in Russia; the first green buds, the early flowers, lambs gamboling in the warm sunlight, streams flowing, children playing. The villagers dance. Tragedy is forgotten. The church bells are joyously rung. A soldier comes riding into the village with a message. A detachment of Austrian prisoners is being brought to be distributed to the farmers for work on the land. The officer in charge arrives and the assignment begins. She shoulders her way through the crowd and points at a' tall, strong prisoner. "I want this one!" she calls out vigorously. The other women smirk, but the commanding officer assigns Jan to her.

All through the summer they work together, and in their work learn to love each other deeply. The gossip by the stream's edge, where the women beat their wash, and the anger of her father-in-law only deepen that love. But the Revolution comes to destroy their quiet. She does not understand why her lover should abandon her and their babe for another war.

Three years of civil war follow. Every village is torn against itself, and this dark woman heads the Red group in her own village. The fighting sweeps that village into its orbit. The Red troops are ten kilometers away. But from the other direction the Whites are coming. Who will go to warn the Red troops? No one dares. With swift decision, she goes herself. Running all the way she stumbles hours later, utterly exhausted, into the Red lines. The sentries give her the field telephone connected with the commander. At headquarters the commander is shaving. She hears his questioning voice and recognizes it. It is Jan!

Weariness is immediately forgotten. Loving speech pours from her. Suddenly he asks of their child. Stunned, she remembers that she left him in the village, and the Whites are coming. Resolutely, she starts back for the village, knowing that torture and perhaps death await her.

The Whites march into the village. They are led by her long-absent husband. He installs his staff and calls a council. His father talks over the situation with the White commander and his officers. They feast and drink.

Into this revelry she comes. There is a dreadful encounter with her

husband. That night she sleeps in the barn with her child, marked by her husband's brutal boots.

But her warning to the Red soldiers has done its work. Through the misty dawn comes the charge of the Red cavalry, led by Jan. The Whites are asleep after the night's carousal. Officers jump out of bed at the sudden shots. Too late. The Red riders sabre their enemies. The White commander rushes out of the staff house, sees the situation at a glance and fires his revolver at Jan. Jan falls; his riderless horse canters slowly off. Immediately, the White commander is cut down.

The fight is over. The villagers come out of hiding. She stands surveying the carnage. Someone indicates to her the body of her husband. She regards it, unmoved. Then another points towards Jan's corpse. She approaches it. Bending over, she recognizes him. Her face is contorted by terrible grief. All night long she keeps lonely vigil over her fallen lover. In the gray dawn, the Red soldiers form to ride onward. In the front rank, rifle strapped to greatcoat, she rides with them.

We filed silently out of the theatre. Possessed by the wondrous beauty of the heroic role we had witnessed, it was impossible for me to speak.

What was the strange power of this unknown woman in a faraway land? Of what nature was the vital force flowing from a fleeting image which stirred the depths of my consciousness?

The secret inner drama of the mystic life remains impenetrable to those who know only the world of ponderable elements. For those who sense the mysterious currents below the surface of material existence, however, there are oceans of strange vital force, transcending reality in power and significance. Men and nations are swayed by this force.

Attuned to its subtle manifestations, my sister remained silent as we glided homeward in our car through the night. Watching thoughtfully, she understood that some crisis of the spirit was taking place. She had long known of my great interest in the U.S.S.R. and my plan to go there.

The exaltation of the evening began to assume definite, incredible form. Floods of energy poured in upon me. I had no desire to sleep. With closed eyes, I reviewed in vivid memory every incident, every gesture of the drama. Here was the perfect symbol of the heroic new woman of revolutionary Russia. In some strange manner, I suddenly felt my destiny bound up with her. She seemed the bridge between the social order in which I had been born and reared and another in travail in a distant land, her country. Between the actual woman and her role there could be

no differentiation. In my mind they were one. I must cross continents and oceans and find this woman even at the ends of the earth. The woman's name was Emma Cessarskaya, but in my mind she figured as the Dark Goddess.

The next evening I returned to the theatre to see the performance again. In the greatest excitement I awaited the opening of the unforgettable first scene. At last, the Pathétique and that glorious dark head! Struggle and sorrow, pain and death, over which her image rose in loveliness and indomitable will on her tragic way.

I sought out the manager of the theatre. We plunged into a discussion of the Russian films. Our conversation centered on Her Way . He quickly understood the profound meaning I had seen in it. In his dress clothes, he got down on his hands and knees on the dusty floor and, seizing a pair of scissors, cut up all of his display cards with photographs of the great actress and presented them to me.

To an American periodical which reviewed foreign films, I wrote of Her Way:[4]

Through the entire range of the drama, from the iron-clad, soul-stifling traditions, the religious rites and marriage enslavement, to the hopeless desolation of war, rending simple men from obscure villages to distant mutilation and death, there is a sodden, engulfing fatefulness. With vast and terrible steps the sombre forces of old Russian cruelty, oppression and degradation stalk through a setting of pastoral beauty and happier peasant folkways.

Over this dark scene soars the indomitable courage of the glorious peasant-woman whose natural majesty dims the splendor of queens, and whose beauty lifts up the spirit in adoration. The profoundly moving characterization Cessarskaya presents is beyond technique. The elemental nature of the central character is so powerfully revealed that it becomes the embodiment of the epic struggle of a great people, up from darkness, fear and misery, towards self-realization and light.

Only a woman steeped in the tumultuous currents of New Russia, only a woman through whose mighty heart those currents flowed, could portray such vital emotions with such fidelity. Never shrinking, running forward to her poignant destiny, illuminating the whole scene by the splendid fire of her dauntless spirit, she becomes the symbol of the glorious woman of the new race!

Under the moving influence of the characterization I had seen, I wrote to the unknown actress, employing for introduction an incident from the life of Richard Wagner, recorded in his Reminiscences .

As a young man he attended a performance by the celebrated singer Mme. Schröder-Devrient. Rushing out into the night, on fire with the beauty of the music, he addressed a letter to the great diva, declaring that if he ever produced any creative work, it would spring from the inspiration he had received that evening. Twenty-five years later at the premiere performance of Die Meistersinger , Mme. Schröder-Devrient, then an old lady, and a sponsor of the opera, drew from her bosom a yellowed letter and handed it to Wagner. It was the one he had written in his youth!

Beginning with this story, I told of the tremendous impression the film had made upon me and the significance of the life of New Russia I had found in it. I alluded to my own work and to my plan to come to her land to participate in its new constructive tasks and of the hope of seeing her.

I did not receive acknowledgment or answer to this letter.

Each night the film was shown, eight altogether, I returned to see it. When the last rending climax had faded and the inexpressibly sad finale of the Pathétique had died away, with that face engraved forever on my consciousness, I went out into the night. Between me and all I had known there was now a widening gulf; before me, the way which was to lead across land and sea, through nations and peoples, over barriers of strange languages and customs. To Russia!

Russia, land of horror and hope, darkness and the new light of social rebirth, misery and music; Russia of upheaval, of vast construction, of stern struggle, of ecstatic joy, of incredible suffering. Russia of tragic destiny. Russia of heroes and martyrs, bearing like her, in their glowing, unconquerable spirits, the undying fires of the future.

From that moment I ceased to live in my immediate existence. My real thoughts and my deepest emotions were already embarked upon the long journey to her land.

The weight of responsibility often crushes out the finest spontaneous expressions of our lives. Freedom to respond to the deepest impulses is the privilege of rare and blessed souls. The great Garibaldi, coming into the harbor of Montevideo, after crossing the ocean to aid the revolutionary Uruguayans, saw through his field glasses the face of a girl in the dense crowd that lined the shore. He immediately lowered a boat and, landing, found her and married her. It was she, the beloved Bianca [Anita Ribeiro da Silva], who rode with him through all the deadly battles of the Uruguayan struggle for independence.

Cutting the ties of an established professional life was a severe and extended process. Many personal affairs in my existence also had to be brought to conclusion. But the vision gleamed unwaveringly before me.

During this period I made every effort to study the experiences of those who had been to the Soviet Union. Among them I talked with Arthur Powell Davis, the distinguished reclamation engineer, whose bitter comments on the paralyzing effects of the bureaucracy were disturbing.

So swiftly did the tide of economic collapse in America run, that when I was ready in 1931 to begin work in the U.S.S.R. I felt myself not merely an individual but the forerunner of thousands of men who had helped to build America and who stared desperately at a blank and hopeless future. With me went their hopes for a new way, which I was to test in my social and technical exploration.

For several years American technical journals had recorded my work in construction. When my approaching departure to the U.S.S.R. was announced, several journals and a section of the liberal American press designated me as their European engineering correspondent.