The First Litigation: ALA's Lawsuit

Shutting down the media campaign was too much for the ALA to swallow. In 1991 the ALA had been promised that, in exchange for accepting AB 99's diversion of funds, there would be no further diversions for the life of the legislation, which would not expire until June 1994. When asked why the agreements of previous years were not being honored, Kassy Perry, the governor's deputy communications director, responded, “That was last year. This is this year.”[36]

Rather than allowing the media campaign to be shut down, the ALA filed a suit against Wilson and Coye on February 21, 1992, arguing that by refusing to sign the contract with the advertising agency, they had violated AB 99, which said that the DHS “shall” run an anti-tobacco media campaign. Significantly, ALA did not challenge the diversion of funds on

Neither AHA nor ACS joined ALA in its lawsuit, although ANR attempted to file a friend of the court brief. ACS was willing, if asked, to state privately its position that the cuts were illegal and a flagrant violation of the will of the people, but it refused to join in the suit. ACS thought it could achieve more working behind the scenes.[20] This view was surprising, since the evidence to date had indicated that health groups won in public venues and lost behind the scenes.

Jennie Cook, ACS lobbyist Theresa Velo, and AHA lobbyist Dian Kiser met with Bill Hauck, the governor's assistant deputy for policy, and Tom Hayes, the director of finance, while the lawsuit was in progress. Whereas ACS and AHA wanted to talk about the anti-smoking program generally, the administration officials seemed to care only about the lawsuit. According to Cook, “The first item on their agenda was the lawsuit. After we explained that our two organizations were not involved, the mood instantly changed and became much more positive.”[60] Cook, Velo, and Kiser attempted to discuss the merits of the program, but Hauck and Hayes wanted to discuss budget problems. Cook continued, “They expressed concern regarding the media's interpretation that the Governor is proposing this [sic] cuts for the tobacco industry. They asked our organizations to help clarify these erroneous statements.”[60] The ACS and AHA did not do so.

Hauck and Hayes apparently recommended that the ACS and AHA representatives talk to Russ Gould, the secretary of health and welfare. They did so, meeting with Gould and Kim Belshé, the deputy secretary for program and fiscal. (In 1993 Belshé would be named director of DHS, where she would be responsible for implementing Proposition 99. In 1988 she had been a spokesperson for the tobacco industry's No on Proposition 99 campaign.) According to Cook, “We informed them that we are not involved in the pending lawsuit, at which time their apprehensions dissipated.”[61] As Cook reported to the ACS leadership,

Gould explained California's fiscal dilemma and assured us that all accounts were looked into along with the Proposition 99 accounts. The decision was made to preserve only direct service funds (i.e., community-based programs). They felt that while the media campaign is a worthwhile program it does not provide direct services; same for the education and research accounts.

They went into some depth explaining the devastating cuts they have to make and that they are uncomfortable with having to make these choices. They asked for an opportunity to reach out to our organizations to explain

― 199 ―the tight spot that the State is in at this time. Gould offered to attend an ACS Board of Directors to do just that.Finally, we requested that we keep an open channel of communication with the Agency through one knowledgeable individual. They both indicated that Belshe would fulfill that role; Belshe invited us to call her to discuss the issue on an on-going basis.

In conclusion, this meeting was very productive in establishing a direct line of communication with the Health & Welfare Agency.[61]

Administration officials were happy to communicate with ACS and AHA. But the communication did not lead to any policy changes.

When asked in 1998 about ACS's decision not to join the 1992 ALA lawsuit, Cook, who was by then the national chair of the ACS board and the chair of TEOC, said, “Cancer and Heart were still a little timid to get into lawsuits. Lung led the way and I think the fact that Lung won it with no real big problem made the other two feel that, `maybe it's time we spoke up.' It wasn't that we didn't want to, it's just that—the old saying about, `we were using public funds and we felt that that's not what the public gave us money for was to sue the governor.' Today, it's a little different [laughter].”[42] In 1992 ACS was unwilling to confront the Wilson Administration in a public forum where the ACS's high public credibility gave it strength. Cook commented that ACS's preference was to avoid confrontation, to “maneuver it, consider it, talk it out, be diplomatic. What we discovered is where tobacco is concerned, you can't be that way.”[42]

On April 24, 1992, the ALA won in court when Judge James Ford of Sacramento Superior Court ruled that Wilson did not have the authority to take funds appropriated for one purpose and use them for another; Ford ordered that the money be used for the authorized media campaign. The big question following the ALA victory was whether the governor would appeal the Superior Court's decision. An appeal would freeze the status quo and keep the media campaign off the air while the case made its way through the courts—possibly for a year or more.

Wilson had appointed Molly Coye director of health services, effective May 29, 1991. Under California law, she could serve for up to one year before she was confirmed by the Senate. If, however, the Senate did not confirm her by the so-called drop-dead date, she would have to leave office. Because of unrelated controversies, the Senate was taking up the matter of Coye's appointment as the litigation over the media campaign was coming to a head. The AHA, which had declined to join the lawsuit, then entered the world of hardball politics.

The AHA convinced the Senate Rules Committee to hold up Coye's confirmation until the deadline for filing an appeal in the media case had passed. At a tense hearing regarding Coye's confirmation, the administration lined up around fifty witnesses to support her, including the CMA, CAHHS, and many other medical organizations. (ALA and ACS took no position on Coye's confirmation.) In the face of this support, Kiser, the AHA's lobbyist, attended the hearing and read a prepared statement that she and Glantz had written, urging the Senate to delay action on Coye's confirmation.[62] The statement read:

Dr. Coye is responsible for overseeing the Health Education Account, including several key components such as the media campaign, the California tobacco survey, and various grants programs to community-based organizations.

The American Heart Association has serious reservations regarding the way these components are being implemented.

These concerns have led the American Heart Association to seriously consider questioning Dr. Coye's confirmation. However, we would like to suggest a positive alternative and that would be to defer her confirmation until she has had an opportunity to remedy the problems that have been created in the implementation of Proposition 99.[63]

That statement went on to stipulate that Coye “execute the media contract that had been awarded, and see that the contractor can continue the campaign free of political interference.”[63]

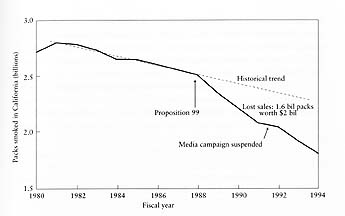

At her May 6 hearing Coye pledged, “I make the commitment and the Governor makes the commitment. We do not plan to appeal the decision.”[64] The governor did not appeal the court decision, Coye was confirmed, the media campaign resumed, and tobacco consumption started to drop again in California. By the end of the 1993-1994 budget period, Californians had consumed 1.6 billion fewer packs of cigarettes (equaling $2 billion in pretax sales) than they would have if historical pre-Proposition 99 consumption patterns had been maintained (figure 13).

The episode demonstrated once more that the anti-tobacco groups exercised the most power in public forums outside of legislative back rooms. In contrast to the tobacco industry and medical interests, which provide substantial campaign contributions to politicians, the health groups get their power from public opinion and public pressure. ALA, which had led the movement to work around the legislative process when it developed Proposition 99, once again succeeded by going outside the Legislature, this time to the courts. AHA solidified ALA's victory by publicly confronting the administration over Coye's confirmation. Program

Figure 13. Impact of the California Tobacco Control Program on cigarette consumption through 1994. Passage and implementation of Proposition 99 was associated with a rapid decline in cigarette consumption in California. During 1991, the year that Governor Pete Wilson took the media campaign off the air and blocked many local programs, the decline stopped. It resumed when the program started up a year later.