The Escalating Fight over Local Ordinances

Things were not going well for the tobacco industry. In particular, its efforts to organize grassroots smokers and encourage them to fight against local tobacco control ordinances on their own was not proving successful, probably because these ordinances enjoyed general support among smokers. As a result, the industry moved to a more sophisticated strategy that involved using public relations firms to fight local ordinances directly, with the local “smoker's rights” groups playing only a cosmetic role.

By September 1990, the tobacco industry was worried about what was going on at the local level. Things were already getting out of control. In a Tobacco Institute memo from Terry Eagan to George Mimshaw, Eagan commented,

Frankly the gravest threat we face comes not from the Legislature but from local government. At present there are disastrous proposed ordinances at work in such major metropolitan areas as the City of Los Angeles, the City of Sacramento and the County of Sacramento. …This new wave of action on local ordinances is being financed by revenues from Proposition 99 as disbursed to local entities by AB 75 of 1989. …Using state allocated Prop 99 funds earmarked for anti-smoking purposes, local governments create citizens committees designed to further the stated goal of a smoke-free society by the turn of the century. More often than not these committees come back to their city councils or boards of supervisors with a proposed smoking ordinance. These ordinances run the gamut from total bans in all public places, including restaurants, bars, and the workplace, to bans on vending machines in areas accessible to minors… .

Given the tremendous amount of money dedicated to anti-smoking purposes it is more than a safe assumption that we will be facing dozens of local actions each year from here on out, either new ordinances or proposals to strengthen old ordinances. Health groups have admitted that they have been unsuccessful in obtaining state-level legislation banning or restricting smoking. They will oppose to the death any attempt on our part to obtain pre-emption of local authorities. They have shifted the battleground to the local level where they are confident they will be more successful. The evidence more than indicates that success will be more readily available to them than in the Legislature. San Luis Obispo, San Francisco, Lodi, and Sacramento testify to their presumption… .

The Tobacco Industry does not have the resources in place to fight local ordinances at a multitude of locations at the same time. We were able to stop the Richmond billboard ordinance with an intense effort by our industry, its consultants, the distributors, the billboard companies and the minority business community.

― 167 ―In Vista and Riverside we were able to convince city attorneys, supervisors and council members that they were pre-empted by state law from regulating vending machines.

In Los Angeles we formed a new restaurant/business organization which is leading the fight against the Braude [clean indoor air] ordinance. But the industry's resources are stretched so thin that things will begin to happen by default.[33] [emphasis added]

By April 17, 1991, the Tobacco Institute had reorganized and added staff to fight local ordinances. Bob McAdam was brought in to replace Ron Saldana as the Tobacco Institute's regional director. The industry was also expanding its California effort by bringing in major political and public relations firms, including the Dolphin Group and Ray McNally and Associates. According to a memo written by Mark Smith to Tom Ogburn of RJ Reynolds,

The days of having to hope for return phone calls from Ron Saldana are fast becoming a bad memory. McAdam is reachable and open about what is going on. And McAdam's weekly conference call not only enhances communication by all parties, but increases the sense of accountability. The Dolphin Group and Ray McNally, both paid for by PM [Philip Morris], but reportable to TI [Tobacco Institute], appear at this early stage to be competent and hard working. The addition of John Hoy to the RJR team has been a big plus that will pay dividends down the road, especially as the L.A. Basin heats up.[34]

The reason for this intense effort was simple: as more ordinances restricted smoking, people stopped smoking or reduced their cigarette consumption, costing the tobacco industry hundreds of millions of dollars in annual sales.[35][36]

The industry's front groups continued to deny or downplay their connections with the tobacco industry. The tobacco companies understood that their role in the effort to stop local clean indoor air ordinances would be controversial and that they had to keep a low profile; they had to rely on other groups to do their bidding. As McAdam explained,

While the industry has coordinated the process, we have effectively used surrogates throughout this effort, and we have several organizations started which serve to facilitate the organization of local interests. These entities provide us with the negotiation necessary to limit our referenda exposure. First, we have created Californians for Fair Business Policy, which is the name given to our operation that has conducted the various referenda, and it is clearly identified as a “tobacco organization.” Then there is the California Business and Restaurant Alliance (CBRA). This organization has a tax exempt status and is operated by The Dolphin Group with assistance from our consultant,

― 168 ―Joe Justin. Finally there is Restaurants for a Sound Voluntary Policy (RSVP) operated by Rudy Cole. While this organization was active in the Los Angeles battle, and to some extent in Bellflower and Culver City, it has not grown since then and does not have a presence outside the Southern California region. A variety of RJR-sponsored local smokers' rights organizations have been created for specific battles to assist in the grassroots effort.[37] [emphasis added]

McAdam observed that the tobacco industry's “strongest weapon” was its mobilization of local businesses: “This has been accomplished through CBRA and our full-time consultant, Joe Justin, and a great deal of work by The Dolphin Group. If our battle is to continue on this level, this part of the operation is essential. If PM [Philip Morris] will continue to fund this group, which again can be triggered by both circumstances and our Regional Vice President, it will fit into our defensive strategy.”[37] McAdam went on to say that “as the opposition gets more aggressive (and they will),” the Tobacco Institute would have to be prepared to respond. He proposed that two new consultants be hired with institute funds but added, “These consultants will be retained by one of our surrogate organizations.”[37]

McAdam also realized that the tobacco industry needed one final piece of the puzzle, evidence that smoke-free ordinances had a negative economic impact: “We need to produce some hard information about the economic impact of the smoking bans. …Now that the bans have had one or two quarters to take effect, we can look at tax data that will be available this fall and create a study that can be used across the state. A Price-Waterhouse study with some credibility in this area would cost $25,000.”[37] The proposed study of California ordinances using tax data never materialized; either it was never conducted or the data, when obtained, showed no adverse effect from the smoke-free restaurant laws.

The tobacco industry's efforts to use the argument that smoke-free restaurant ordinances hurt the restaurant business was eventually discredited as a result of a chance meeting of Lisa Smith and Professor Stanton Glantz of the University of California, San Francisco, in the ornate lobby outside the Los Angeles City Council chambers in 1990, just after the tobacco industry defeated a proposed clean indoor air ordinance. Smith was working on local ordinances in the Sacramento area and had attended the hearing to see the industry in action; Glantz was at the hearing to testify about the dangers of secondhand tobacco smoke. After the hearing, Glantz expressed his doubt over the now-familiar industry claim that smoke-free ordinances reduced restaurant sales by 30 percent. The

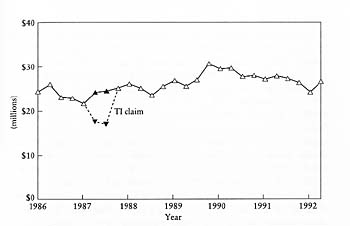

Figure 11. Beverly Hills restaurant revenues, 1986-1992. The 100% smoke-free restaurant ordinance did not reduce revenues by 30% when it was in force in Beverly Hills, as the tobacco industry had claimed. The ordinance (solid triangles) actually had no significant effect on sales. Source: S.A. Glantz and L.R.A. Smith, The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants on restaurant sales, Am J Pub Health 1994;84:1081-1085. Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Public Health (copyright 1994 by American Public Health Association)

This research would cause the industry problems. According to a 1993 internal Philip Morris e-mail, “The economic arguments which only a year ago prevented a ban in Los Angeles and San Francisco, are losing the ability to pursuade [sic], as more and more communities, small and

To support the industry's local referenda effort in the coming year, 1992, McAdam wanted $750,000 in ready reserve with Californians for Fair Business Policy. This money would be used to fund signature-gathering if it became necessary in Los Angeles. He also wanted $40,000 to fund efforts in each of four elections: Paradise, El Dorado County, Oroville, and Visalia, where the industry had forced local clean indoor air laws onto the ballot, and $1,500,000 for the renewed effort in Sacramento County. In total, the California Local Referendum Project required $2,060,000 for its first year of operation.[37] In the end, the industry spent $1.71 million attempting to overturn ordinances in Sacramento County, Oroville, Paradise, El Dorado County, and Visalia. Each company's contribution was based on its share of the prior year's production of cigarettes and manufactured tobacco.[45]

With a more organized and sophisticated strategy, the tobacco industry was prepared to continue its fights against local ordinances all over the state. When confronted with an ordinance, the industry would first attempt to force the local government to drop or weaken it; if this ploy failed, the industry would then start a referendum petition drive to pressure elected officials to modify the ordinance rather than incur the cost of an election. If these two steps failed, the industry would mount a well-funded campaign to defeat the ordinance at the polls.