9. The Battle over Local Tobacco Control Ordinances

Unlike the media campaign and school programs, which started from scratch after the voters passed Proposition 99, the effort to pass local tobacco control ordinances was already well under way by the time that the Department of Health Services (DHS) set up its tobacco control program. By the time DHS started to implement Proposition 99 in 1990, 213 California communities, working with Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR), had passed local clean indoor air ordinances. After Proposition 99 passed, this effort received a substantial boost. DHS, the local lead agencies (LLAs), and the local coalitions rapidly adopted the local ordinance strategy that had grown out of Propositions 5, 10, and P a decade earlier and that ANR had been pursuing since. The media campaign raised public awareness of secondhand smoke issues, and DHS provided resources and technical assistance with which the LLAs and other groups could engage the public in developing and implementing local tobacco control policies.

The tobacco industry also recognized the power of local action. It worked in the shadows to undermine local efforts, because it lacked credibility with the public. In a 1989 opinion poll conducted by the Gallup Organization, the Tobacco Institute received the most unfavorable rating among nine nationally recognized interest groups.[1] This poll confirmed the results of a secret poll done for the Tobacco Institute by Tarrance and Associates in 1982, which found that overt industry opposition increased

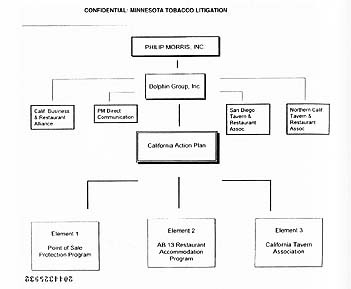

Figure 10. Philip Morris's secret California Action Plan network. Philip Morris hired the Dolphin Group to create this coalition of “business and restaurant associations” to obscure the industry's role in orchestrating opposition to local clean indoor air laws. Source: Philip Morris(?). 1994 California Plan, 1994 (Bates No. 2022816070/6080).

While hundreds of California communities would enact local tobacco control ordinances, a few of these battles with the tobacco industry will capture

Beverly Hills

In 1987 the Beverly Hills City Council proposed a 100 percent smoke-free requirement for the city's restaurants. This ordinance would have been only the second such ordinance in the country and the first in California. For the proposal to become law, the council had to approve it on two separate readings. The ordinance passed its first reading without public opposition.

Between the first and second readings, the Tobacco Institute hired political consultant Rudy Cole to create the Beverly Hills Restaurant Association (BHRA) to oppose the ordinance.[4] To drum up membership for BHRA, Ron Saldana, the Tobacco Institute's regional director, spoke to the local restaurant owners and the Chamber of Commerce to “make them aware of the potential impact the ordinance will have on the community.”[5] The Tobacco Institute's role in creating the BHRA was not disclosed. At the second reading, Cole appeared as spokesperson of the newly formed Beverly Hills Restaurant Association to protest the ordinance. Nonetheless, the city council unanimously passed it in March 1987, making Beverly Hills approximately the 130th community in California to pass a clean indoor air ordinance and the state's first to make restaurants entirely smoke free.

Mickey Kantor, a prominent attorney in the well-connected law firm of Manatt, Phelps, Rothenberg and Phillips, was hired to represent the BHRA. (Kantor, a power in California Democratic politics, went on to become President Bill Clinton's foreign trade representative, secretary of commerce, and a key personal advisor in the Monica Lewinsky controversy.) The BHRA attempted to get a temporary court order to stop the implementation of the ordinance, but the effort failed.[6] Kantor then filed a lawsuit against the city claiming that the ordinance was unconstitutional, discriminatory, and disastrous for business. This action also failed.[7] The Tobacco Institute paid BHRA's legal bills.[8]

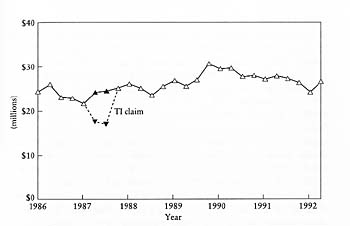

Having failed to void the law in court, the BHRA complained that restaurants had suffered a 30 percent drop in business after the ordinance took effect.[9-11] While being touted widely in tobacco industry publications, this claim was not challenged or investigated by the health community at the time. As a result, the claim of a serious impact on business

Six years later, Barry Fogel, BHRA's nominal president, wrote to the New York City Council to endorse its planned ordinance making restaurants smoke free. He recounted the history of BHRA:

There was no Beverly Hills Restaurant Association before the smokefree ordinance. We were organized by the tobacco industry. The industry helped pay our legal bills in a suit against Beverly Hills. The industry even flew some of our members by Lear Jet to Rancho Mirage, another California city considering smokefree restaurant legislation, to testify before their City Council against a similar smokefree ordinance. Tobacco Institute representatives attended some of our meetings.

The tobacco industry repeatedly claimed that Beverly Hills restaurants suffered a 30% decline in revenues during the 5 months that the smokefree ordinance was in effect. Figures from the State Board of Equalization using sales tax data, however, showed a slight increase in restaurant sales.

I regret my participation with the tobacco industry. In 1991 when I learned that secondhand smoke caused cancer, I made all Jacopo's restaurants 100% smokefree, including bar and outdoor patio areas. Even in this difficult economic climate, our sales have risen.[12]

The tobacco industry could claim a victory in Beverly Hills because this was the first time a nonsmokers' rights ordinance had been weakened after it was enacted. Even so, while Beverly Hills represented a setback for clean indoor air advocates, the 60 percent minimum nonsmoking requirement still left Beverly Hills with the strongest ordinance in the state at that time.

Lodi

The movement toward a smoke-free society took a big step forward in the small farming community of Lodi (population 50,000) in California's Central Valley. Armed with the recent US Environmental Protection Agency report that identified secondhand smoke as a Class A carcinogen,[13] the San Joaquin County Smoking Action Coalition, a group of residents formed to promote smoking ordinances, approached the Lodi City Council in December 1989 to request consideration of a smoking control ordinance. Sandy Stoddard, a coalition member and American Cancer Society (ACS) staff member, had grown up in Lodi and knew three of the five council members personally.[14]

During the spring of 1990, the Lodi City Council formally considered a smoking ordinance. After promoting the ordinance, the community health activists took a back seat as elected officials, particularly Mayor Randy Snider, molded the proposal. On May 16, the city council voted 4-1 in favor of an ordinance prohibiting smoking in almost all indoor public places. (Bars, motel and hotel rooms, retail tobacco stores, private offices, and residences were excluded.) Before the proposal became law, the council was to vote on it again, within one month after the initial vote.

During the intervening three weeks, RJ Reynolds learned of the proposal and sent an Action Alert letter to residents of Lodi, urging them to call their council members and attend the council meeting to voice opposition to the proposal. The names and telephone numbers of council members were included in the letter, as well as a toll-free RJ Reynolds telephone number for anyone with questions.

Meanwhile, in June 1990, a group called Taxpayers United for Freedom (TUFF) was formed in Lodi to oppose the ordinance. TUFF claimed to be a grassroots organization that did not receive support from the tobacco industry. Adam Dados, a spokesperson for the group, said, “We've only received some ashtrays and lighters from the tobacco companies.”[15]

In contrast to the first city council meeting, where little opposition was evident, the June 6, 1990, meeting was a raucous affair with 400 people attending, some hissing and booing during testimony by the ordinance's supporters. Local physicians, ANR, and the local chapters of the ACS and AHA spoke in favor of the ordinance. ANR's executive director, Julia Carol, said after the meeting that she had been to many similar hearings but “none so hostile.”[16] Those who spoke in opposition to the proposal were all local residents. Dados presented petitions with over 3,000 signatures to the council.

Despite efforts by RJ Reynolds and TUFF to organize opposition to the ordinance, the Lodi City Council passed it on second reading by a 4-1 vote. Lodi became the first 100 percent smoke-free city in the United States.

After the vote, Bill Stamos, a Lodi resident, armchair legal scholar, nonsmoker, and opponent of the ordinance, drafted a referendum for TUFF to force a popular vote on the ordinance.[17] Supporters of the referendum had thirty days to gather 2,369 signatures for it; they turned in petitions with 5,051 signatures. The council had two choices: repeal the ordinance or put it on the ballot. They voted to let the people of Lodi decide.

Soon after TUFF submitted the petitions, ordinance supporters formed the Lodi Indoor Clean Air Coalition (LICAC). This group, led by a physician and a retired waitress, was formed without the assistance of any established health organization. On July 10 LICAC held a public meeting; about 175 local residents attended, $2,000 was raised, and volunteers were identified for the campaign. Assuming that TUFF would mount a well-organized campaign, LICAC decided to hire a professional campaign coordinator.

During the initial weeks LICAC mobilized support and asked for contributions from concerned citizens through advertisements in the local newspaper. Most of the larger contributions came from medical professionals. Of the $6,250 in contributions amounting to $100 or more, $3,200 came from individual doctors and medical companies, groups usually hesitant to become involved in local political campaigns.[18] LICAC raised a total of $12,025, almost half of which was in contributions of less than $100.[19]

Independently of LICAC, the local ACS sent out approximately 1,250 letters to patients and volunteers in Lodi urging them to support the referendum on the smoking ordinance.[14] No effort was made by the other local voluntary health agencies (ALA or AHA) to mobilize support for the referendum. The California Medical Association was asked to support LICAC but did not contribute to the campaign.[20]

LILAC's campaign strategy was to discredit the opposition, not by attacking TUFF directly but by indirectly labeling the group as a tobacco industry front.[21] LICAC used newspaper advertisements borrowed from health activists in Fort Collins, Colorado, who had faced a similar campaign in 1984. These advertisements included one portraying a tobacco spokesman waving his cigar, saying, “So long Lodi, it's been good to know you,” as he hopped into his limousine to leave town after the election, his briefcase full of tobacco industry money.

TUFF's advertisements focused on smoking as an issue of rights and freedoms, embedded in the U.S. Constitution. One ad, framed with the American flag, proclaimed, “The smoking ban…is anti-american and in violation of the very precepts of our inalienable rights as Americans.”[15] TUFF also used the specter of severe punishments for ordinance offenders. One cartoon showed two prisoners in a jail cell, one saying, “I'm in here for murder, extortion and grand theft! What did you do?” The other replied, “I lit up a cigarette in Lodi!”[15]

TUFF collected more than $11,439 in monetary contributions from

In November, despite the efforts of TUFF and the tobacco industry, the voters in Lodi approved the ordinance by an overwhelming 60 percent (1,986 to 1,470).

Even after they lost the election, TUFF did not give up.[25] They threatened a recall of the council members who voted for the ordinance and targeted Mayor Randy Snider when he ran for reelection; Snider won. They filed a legal challenge against the ordinance, which failed. They attempted to organize noncompliance. In the end, however, the ordinance went into effect and was enforced, making Lodi the first city in California to enact and maintain a law requiring 100 percent smoke-free restaurants.

Other cities began to follow suit. In August 1990 the coastal college town of San Luis Obispo implemented the nation's first law creating smoke-free bars.

Sacramento

While the battle in Lodi was taking place, both Sacramento and Sacramento County enacted strong ordinances ending smoking in all public and private workplaces and in all public places, including restaurants.

The most significant factor in Sacramento's success was the strong connection between the American Lung Association of Sacramento-Emigrant Trails and community leaders. The Sacramento ALA had recruited influential civic leaders from various backgrounds to serve on

The health advocates on the task force successfully pushed to recommend a total smoke-free policy in the workplace. They also wanted to increase the percentage of nonsmoking seats in restaurants from a minimum of 10 percent (under the previous ordinance) to 50 percent. The task force recommendations went to the Environmental Commission, which held public hearings on the recommendations. Significantly, the Chamber of Commerce, an organization representing 2,600 local businesses, endorsed the recommendations.

At the hearing before the County Board of Supervisors, the tobacco industry flew in its “expert witnesses” who frequently testify before legislative bodies. Among those out-of-towners testifying against the ordinance were Gray Robertson of Fairfax, Virginia, a tobacco industry “consultant” who had been set up in a series of businesses by Philip Morris to play down secondhand tobacco smoke as a significant cause of indoor air pollution;[26] David Weeks, a physician from Boise, Idaho; Malinda Sidak, an attorney from Covington and Burling in Washington, sent to represent the Tobacco Institute; and John C. Fox, an attorney from San Francisco.

County Supervisor Sandra Smoley, a registered nurse and ACS volunteer, voted against the ordinance. (Smoley had accepted a $250 contribution from the tobacco industry in 1988.[28]) Echoing the tobacco industry, Smoley said that if the county approved such stringent measures against smoking, then it should also “outlaw alcohol and fatty foods and mandate that everyone ride their bikes.”[29] On October 2, 1990, despite the industry's efforts, the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors passed the ordinance on a 3-2 vote, making all workplaces and most public places smoke free. Restaurants were to become smoke free with a three-year phase-in period; bars were exempted. A week later, on October

The tobacco industry did not give up.

On October 3, the same day that the County Board of Supervisors passed the ordinance, the Tobacco Institute loaned $20,000 to a referendum campaign committee that had not yet formed.[30] On October 5, three days after the county vote and prior to the city council vote, Sacramentans for Fair Business Policy (SFBP) filed a statement of organization to force a referendum on the smoking ordinances. Tim Pueyo, the San Francisco political consultant for RJ Reynolds, was hired to run the campaign for SFBP. The same day, the company contributed almost half of its total contribution of $134,000. The other four major domestic cigarette manufacturers at the time, American Brands, Philip Morris, Lorillard, and Brown and Williamson, had all contributed thousands of dollars by the end of October. As of December 31, 1990, SFBP had received $375,971 in cash, loans, and services, only $9,150 (2.4 percent) of which came from nontobacco interests, mostly restaurants. As in past campaigns, the tobacco companies' contributions to the referendum effort were in proportion to their market shares.[31]

In Sacramento SFBP hired Nielsen, Merksamer, the tobacco industry's usual law firm in California, to fulfill legal obligations. Within two weeks, SFBP was using the tobacco money to distribute referendum petitions through the mail. Despite being organized and funded by outof-state tobacco companies, throughout the campaign SFBP posed as a local independent organization. On November 1 Pueyo told the Sacramento Bee that his organization “is a grassroots coalition of business operators and individuals who oppose government sticking its nose in our business.”[32]

The county required 30,433 signatures and the city required 19,334 to force referenda. Most of the tobacco money went to a Sacramento company specializing in petition drives. Of the approximately 60,000 signatures submitted to the county, enough were valid to force a referendum. Of the 31,135 signatures submitted to the city, not enough were valid to meet the minimum requirement. Therefore, the county ordinance was delayed until the next countywide election in 1992, which gave the tobacco industry another chance to overturn it. The city's ordinance went into effect on December 14, 1990.

The Escalating Fight over Local Ordinances

Things were not going well for the tobacco industry. In particular, its efforts to organize grassroots smokers and encourage them to fight against local tobacco control ordinances on their own was not proving successful, probably because these ordinances enjoyed general support among smokers. As a result, the industry moved to a more sophisticated strategy that involved using public relations firms to fight local ordinances directly, with the local “smoker's rights” groups playing only a cosmetic role.

By September 1990, the tobacco industry was worried about what was going on at the local level. Things were already getting out of control. In a Tobacco Institute memo from Terry Eagan to George Mimshaw, Eagan commented,

Frankly the gravest threat we face comes not from the Legislature but from local government. At present there are disastrous proposed ordinances at work in such major metropolitan areas as the City of Los Angeles, the City of Sacramento and the County of Sacramento. …This new wave of action on local ordinances is being financed by revenues from Proposition 99 as disbursed to local entities by AB 75 of 1989. …Using state allocated Prop 99 funds earmarked for anti-smoking purposes, local governments create citizens committees designed to further the stated goal of a smoke-free society by the turn of the century. More often than not these committees come back to their city councils or boards of supervisors with a proposed smoking ordinance. These ordinances run the gamut from total bans in all public places, including restaurants, bars, and the workplace, to bans on vending machines in areas accessible to minors… .

Given the tremendous amount of money dedicated to anti-smoking purposes it is more than a safe assumption that we will be facing dozens of local actions each year from here on out, either new ordinances or proposals to strengthen old ordinances. Health groups have admitted that they have been unsuccessful in obtaining state-level legislation banning or restricting smoking. They will oppose to the death any attempt on our part to obtain pre-emption of local authorities. They have shifted the battleground to the local level where they are confident they will be more successful. The evidence more than indicates that success will be more readily available to them than in the Legislature. San Luis Obispo, San Francisco, Lodi, and Sacramento testify to their presumption… .

The Tobacco Industry does not have the resources in place to fight local ordinances at a multitude of locations at the same time. We were able to stop the Richmond billboard ordinance with an intense effort by our industry, its consultants, the distributors, the billboard companies and the minority business community.

― 167 ―In Vista and Riverside we were able to convince city attorneys, supervisors and council members that they were pre-empted by state law from regulating vending machines.

In Los Angeles we formed a new restaurant/business organization which is leading the fight against the Braude [clean indoor air] ordinance. But the industry's resources are stretched so thin that things will begin to happen by default.[33] [emphasis added]

By April 17, 1991, the Tobacco Institute had reorganized and added staff to fight local ordinances. Bob McAdam was brought in to replace Ron Saldana as the Tobacco Institute's regional director. The industry was also expanding its California effort by bringing in major political and public relations firms, including the Dolphin Group and Ray McNally and Associates. According to a memo written by Mark Smith to Tom Ogburn of RJ Reynolds,

The days of having to hope for return phone calls from Ron Saldana are fast becoming a bad memory. McAdam is reachable and open about what is going on. And McAdam's weekly conference call not only enhances communication by all parties, but increases the sense of accountability. The Dolphin Group and Ray McNally, both paid for by PM [Philip Morris], but reportable to TI [Tobacco Institute], appear at this early stage to be competent and hard working. The addition of John Hoy to the RJR team has been a big plus that will pay dividends down the road, especially as the L.A. Basin heats up.[34]

The reason for this intense effort was simple: as more ordinances restricted smoking, people stopped smoking or reduced their cigarette consumption, costing the tobacco industry hundreds of millions of dollars in annual sales.[35][36]

The industry's front groups continued to deny or downplay their connections with the tobacco industry. The tobacco companies understood that their role in the effort to stop local clean indoor air ordinances would be controversial and that they had to keep a low profile; they had to rely on other groups to do their bidding. As McAdam explained,

While the industry has coordinated the process, we have effectively used surrogates throughout this effort, and we have several organizations started which serve to facilitate the organization of local interests. These entities provide us with the negotiation necessary to limit our referenda exposure. First, we have created Californians for Fair Business Policy, which is the name given to our operation that has conducted the various referenda, and it is clearly identified as a “tobacco organization.” Then there is the California Business and Restaurant Alliance (CBRA). This organization has a tax exempt status and is operated by The Dolphin Group with assistance from our consultant,

― 168 ―Joe Justin. Finally there is Restaurants for a Sound Voluntary Policy (RSVP) operated by Rudy Cole. While this organization was active in the Los Angeles battle, and to some extent in Bellflower and Culver City, it has not grown since then and does not have a presence outside the Southern California region. A variety of RJR-sponsored local smokers' rights organizations have been created for specific battles to assist in the grassroots effort.[37] [emphasis added]

McAdam observed that the tobacco industry's “strongest weapon” was its mobilization of local businesses: “This has been accomplished through CBRA and our full-time consultant, Joe Justin, and a great deal of work by The Dolphin Group. If our battle is to continue on this level, this part of the operation is essential. If PM [Philip Morris] will continue to fund this group, which again can be triggered by both circumstances and our Regional Vice President, it will fit into our defensive strategy.”[37] McAdam went on to say that “as the opposition gets more aggressive (and they will),” the Tobacco Institute would have to be prepared to respond. He proposed that two new consultants be hired with institute funds but added, “These consultants will be retained by one of our surrogate organizations.”[37]

McAdam also realized that the tobacco industry needed one final piece of the puzzle, evidence that smoke-free ordinances had a negative economic impact: “We need to produce some hard information about the economic impact of the smoking bans. …Now that the bans have had one or two quarters to take effect, we can look at tax data that will be available this fall and create a study that can be used across the state. A Price-Waterhouse study with some credibility in this area would cost $25,000.”[37] The proposed study of California ordinances using tax data never materialized; either it was never conducted or the data, when obtained, showed no adverse effect from the smoke-free restaurant laws.

The tobacco industry's efforts to use the argument that smoke-free restaurant ordinances hurt the restaurant business was eventually discredited as a result of a chance meeting of Lisa Smith and Professor Stanton Glantz of the University of California, San Francisco, in the ornate lobby outside the Los Angeles City Council chambers in 1990, just after the tobacco industry defeated a proposed clean indoor air ordinance. Smith was working on local ordinances in the Sacramento area and had attended the hearing to see the industry in action; Glantz was at the hearing to testify about the dangers of secondhand tobacco smoke. After the hearing, Glantz expressed his doubt over the now-familiar industry claim that smoke-free ordinances reduced restaurant sales by 30 percent. The

Figure 11. Beverly Hills restaurant revenues, 1986-1992. The 100% smoke-free restaurant ordinance did not reduce revenues by 30% when it was in force in Beverly Hills, as the tobacco industry had claimed. The ordinance (solid triangles) actually had no significant effect on sales. Source: S.A. Glantz and L.R.A. Smith, The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants on restaurant sales, Am J Pub Health 1994;84:1081-1085. Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Public Health (copyright 1994 by American Public Health Association)

This research would cause the industry problems. According to a 1993 internal Philip Morris e-mail, “The economic arguments which only a year ago prevented a ban in Los Angeles and San Francisco, are losing the ability to pursuade [sic], as more and more communities, small and

To support the industry's local referenda effort in the coming year, 1992, McAdam wanted $750,000 in ready reserve with Californians for Fair Business Policy. This money would be used to fund signature-gathering if it became necessary in Los Angeles. He also wanted $40,000 to fund efforts in each of four elections: Paradise, El Dorado County, Oroville, and Visalia, where the industry had forced local clean indoor air laws onto the ballot, and $1,500,000 for the renewed effort in Sacramento County. In total, the California Local Referendum Project required $2,060,000 for its first year of operation.[37] In the end, the industry spent $1.71 million attempting to overturn ordinances in Sacramento County, Oroville, Paradise, El Dorado County, and Visalia. Each company's contribution was based on its share of the prior year's production of cigarettes and manufactured tobacco.[45]

With a more organized and sophisticated strategy, the tobacco industry was prepared to continue its fights against local ordinances all over the state. When confronted with an ordinance, the industry would first attempt to force the local government to drop or weaken it; if this ploy failed, the industry would then start a referendum petition drive to pressure elected officials to modify the ordinance rather than incur the cost of an election. If these two steps failed, the industry would mount a well-funded campaign to defeat the ordinance at the polls.

Long Beach

The industry's stepped-up efforts were evident in the later local ordinance campaigns, such as the one in Long Beach, a major urban center. The initiation and development of Long Beach's ordinance came from the Long Beach Tobacco Control Coalition, a broad-based advisory group of civic, academic, and health leaders and staff from the Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services.

In January 1991 the coalition and the health department asked the Long Beach City Council's Quality of Life Committee to strengthen the city's existing ordinance, and the committee went on to recommend that the council adopt an ordinance that would have ended smoking in public places and the workplace, made at least two-thirds of restaurant seating nonsmoking, and restricted vending machines and billboard advertising.

The ordinance was publicly opposed by local restaurant and business owners, the Long Beach Chamber of Commerce, and Rudy Cole of RSVP. (At the time, Cole denied that he was or ever had been paid by the tobacco industry.) Fred Karger of CBRA never testified publicly but attended several city council meetings with the vice president of governmental affairs for the Chamber of Commerce. Karger, at a later Quality of Life Committee meeting, even refused to answer questions from Councilman Evan Braude. Karger's dual role as chief executive officer of CBRA and executive vice president of the Dolphin Group was not widely known, nor was his association with the tobacco industry.

Despite the tobacco industry's efforts, the council exceeded the Quality of Life Committee's recommendations, stipulating that smoking would be completely ended in restaurants by 1994. After lobbying efforts failed to stop the ordinance, the tobacco industry, acting through Californians for Fair Business Policy (CFBP), initiated a referendum petition drive to suspend the ordinance. CFBP spent $87,410 on the petition drive, virtually all of which came from tobacco companies, but the level of industry involvement was not known at the time.

Controversy surrounded the petition drive and the signature gatherers. CFBP hired Kimball Petition Management to collect the necessary signatures. Complaints were reported to city officials of signature gatherers misrepresenting the content and nature of the petition drive. According to CFBP's disclosure statement, the petitioning firm employed at least eighteen signature gatherers who did not live in Long Beach. Despite the objections of health advocates to the tobacco industry's questionable tactics, enough signatures were validated to suspend the ordinance. No investigation of the allegations of misrepresentation or the use of out-of-town signature gatherers was conducted.

Validating the signatures cost Long Beach $1,861.[46] At the time, an election to decide the issue was estimated to cost Long Beach approximately $500,000; this figure was later lowered to $170,000. Rather than incur the cost, the city council rescinded the ordinance and drafted one

Placer County

Placer County is located in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada range northeast of Sacramento. The Placer County Tobacco Control Coalition (PCTCC), similar to the one in Long Beach, played a key role in developing and passing tobacco control ordinances in the county and several of its cities. During 1991 the PCTCC initiated ordinances in meetings with city managers, arranged study sessions for city councils in the municipalities of Auburn and Roseville, and provided model ordinances as well as written support and public testimony.

The tobacco industry recognized that it could not stop all legislative activity, so it settled on a fall-back position of supporting weak, ineffectual ordinances in the hope that they would forestall tough local tobacco control regulations. By April 25, 1991, the tobacco industry had identified an opportunity to get its “model” ordinance adopted in Placer County.[47] The model ordinance provided for 50 percent of a restaurant's space to be designated as a nonsmoking area as well as for workplace smoking policies to be established by the individual employer. Although the industry proposal was denounced by health groups, it indicated how far and how fast the issue of clean indoor air had advanced in California: the industry's proposed law was stronger than either Proposition 5 or Proposition 10, which the industry had spent over $10 million defeating just a decade earlier.

In Placerville the industry worked through its California Business and Restaurant Alliance (CBRA). In an April 25 memo, Randy Morris, regional director of the Tobacco Institute, wrote to Kent Rhodes, the local CBRA counsel, to specify procedure: “Naturally, this proposal [the industry's model ordinance] is not set in concrete, however, significant changes to the ordinance's provisions, i.e. increasing penalties, further smoking restrictions, etc., must be cleared with appropriate institute staff: the undersigned and Bob McAdam, Vice President for Special Projects. T.I. Staff will then review proposed changes with appropriate member-company personnel, to wit: Sandy Timpson of Philip Morris

In early summer the PCTCC began to develop an ordinance for the county similar to those being passed in the cities. (The city of Colfax also passed an ordinance in mid-August with the help of the PCTCC.) By this time, the tobacco industry had started to intervene aggressively with its new strategy. On November 1, 1991, the Sacramento Restaurant and Merchant Association (SRMA), which was a vehicle for Ray McNally, cosponsored a meeting to organize opposition and select individuals to speak at the Board of Supervisors' November 6 hearing. Diann Rogers and Rosabel Tao of SRMA (employees of Ray McNally) conducted the meeting and stated that SRMA was assisting other communities against similar tobacco control ordinances. They distributed detailed information explaining exactly what local individuals should do to oppose the county ordinance. Rogers asserted that the ordinance would adversely affect the local economy, impose too much government regulation, and infringe on individual rights. The meeting also presented strategies to counter health advocates' efforts. Rogers stressed that health advocates would claim that the tobacco industry was assisting the opposition but that it was important to deny such involvement—such claims would damage the opposition's credibility and the allegations of industry involvement were not true.

The tobacco industry's new strategy succeeded in mobilizing local opposition. The issues brought up at the November 1 meeting were raised, and the tactics applied, by opponents at the Board of Supervisors' hearing later that week. Rogers and Tao attended but did not testify. Although the ordinance had strong support from two supervisors, it was defeated by a 3-2 vote. A compromise ordinance—one weaker than those adopted in the nearby Sierra Nevada foothill communities of Auburn, Roseville, and Colfax—was passed.

The tobacco industry continued to develop an aggressive local strategy to combat the efforts of local health professionals who were aided by resources and education programs funded by Proposition 99. By November 27, 1991, McAdam was formalizing the Tobacco Institute's “California Local Referenda Program.” According to McAdam,

In the absence of a preemptive state law governing smoking restrictions, we have confronted—and will continue to confront—an unprecedented threat of workplace and restaurant smoking ban actions at the local level in California. Either through the ballot box by referenda or through reasonable compromise forged with local officials, this increasing threat of local smoking bans must be challenged… .

The past eight months of operating at the local level have given us some substantial insight into what organization and resources have been most effective in waging this particular battle to stop these prospective bans.[37] [emphasis added]

The industry mounted a multi-million-dollar campaign using professional public relations and political campaign firms to directly lobby for and organize opposition against local tobacco control ordinances.

The Sacramento Battle over Measure G

While the 1990 petition drive against the Sacramento city ordinance did not collect enough valid signatures, the county petition drive did yield enough signatures to suspend the ordinance. The Board of Supervisors decided to place the issue on the June 1992 ballot, where it appeared as Measure G.

In Sacramento Ray McNally worked through the SRMA, and the Dolphin Group worked through the CBRA, to conceal the tobacco industry's role in mobilizing opposition to the ordinance.

In December 1991 representatives from the ALA, ACS, AHA, the Sacramento/El Dorado Medical Society, and the Sacramento Sierra Hospital Conference formed Citizens for Healthier Sacramento/Yes on Measure G (CHS). Early in 1992, CHS commissioned a poll to plan its campaign to defend the ordinance. Seventy-two percent of those surveyed supported the county's tobacco control ordinance. The survey also showed that if people knew that Sacramentans for Fair Business Practices was actually a “front” for the tobacco industry, 48 percent would be more likely to vote for the ordinance, and 69 percent felt that such use of a front organization was “dishonest.”[48]

The tobacco industry, through CFBP, spent $1,775,379 on its campaign to defeat Measure G, using mailers, radio advertisements, television spots, personalized absentee ballot registration forms, and a Kentucky-based telephone bank. The industry's strategy again emphasized that the ordinance would lead to unneeded bureaucracy, waste taxpayer dollars, and create “cigarette police.”

CHS anticipated a major tobacco industry campaign against the ordinance, but realized it could not match the tobacco industry's spending. Instead, it concentrated on raising an adequate budget to run an aggressive grassroots campaign with two key strategies: using the media to constantly inform voters of the tobacco industry's involvement against Measure G and educating organizations in Sacramento County about Measure G and the industry's misleading campaign advertisements.

CHS cultivated substantial media coverage and publicity for Measure G, which yielded nearly 100 newspaper, television, and radio stories. This media attention educated the public about how much the tobacco companies were spending and reported the false claims and controversy surrounding CFBP's campaign commercials and advertisements. This effort led three local newspapers to publish editorials supporting Measure G and criticizing the industry's involvement in Sacramento. The Business Journal warned, “They'll [tobacco companies] masquerade as smart, smooth-talking yuppies, complaining in savvy tones on your TV and radio about how Big Brother is at it again. But don't forget who they really are—tobacco companies that don't give a damn about small business or civil liberties, let alone public health.”[49]

In addition to its media campaign, CHS used two other key tactics. In April and May, CHS community outreach volunteers visited approximately sixty-five groups to neutralize the tobacco industry's misleading campaign messages and draw key support for the ordinance. Since CHS could not hope to match the industry's television or professional mailer campaigns, CHS got its campaign messages out by spending most of its money ($35,000) on radio advertisements attacking the tobacco industry during the final three weeks of the election.

A turning point in the election was a mailer sent out by CFBP one week before voting took place. Aiming to show that Measure G would create unnecessary “cigarette patrols,” the mailer listed several fake emergency telephone numbers, including a number for the “cigarette patrol.” Residents were encouraged to place these numbers near their telephones. The back of the mailer featured a copy of a memo from the Sacramento

CHS's aggressive media strategy, its active community outreach program, and other local grassroots efforts led to a 56 percent to 44 percent victory for Measure G.

The Tobacco Industry's Plan: “California's Negative Environment”

By January 11, 1991, the Tobacco Institute's State Activities Division had prepared a secret report entitled “California: A Multifaceted Plan to Address a Negative Environment.”[4] The report documented how successful the tobacco control advocates had been:

With the passage of Proposition 99—the $500 million annual tobacco tax increase measure adopted in November, 1988—the industry faces statewide funding of local anti-tobacco activity, including local measures to ban smoking in workplaces, restaurants and most other public places.

Ten years ago, the assumption was that most law makers and members of the public who thought about the issue viewed smoking as an occasional nuisance. Today, it seems that many view tobacco smoke as dangerous to the health of nonsmokers.[4]

The report listed three long-term strategies: to “adopt a reasonable statewide smoking law, with preemption”; to “redirect Proposition 99 funding away from direct anti-tobacco lobbying and other activities”; and to “reduce or eliminate Proposition 99 funding.” In the interim, the industry was to “assemble a legislative team to monitor and defeat local smoking restriction ordinances in California.” The team working on local strategies had a budget of $520,000 in 1991 and $2,085,000 in 1992, with the understanding that “as it becomes necessary to exercise our referenda option in various communities, this amount could increase greatly.”[4]

In 1992 Kurt L. Malmgren, the Tobacco Institute's senior vice president for state activities, prepared a report for Samuel Chilcote, president of the Tobacco Institute, in which he generalized from the tobacco industry's experiences in California, Massachusetts, and Washington State to design an “Expanded Local Program” for the tobacco industry to use

- Sophisticated monitoring of local ordinance introductions

- Ability to respond quickly with locally-based advocates

- Local consultants who can go door-to-door to educate restaurateurs, business leaders, minority group leaders, representatives from organized labor, and other potential allies

- The ability to rightfully project a local concern about a given anti-tobacco ordinance, making it more difficult for anti-tobacco leaders to say, “The only people who oppose this ordinance are the out-of-state tobacco companie.”

- Reasonably coordinated and effective means to trigger direct mail campaigns, phone bank operations and other contacts[50] [emphasis in original]

Malmgren also cited one of the Tobacco Institute's strengths in California: “The industry team quickly employs coalition coordinators who can—quickly and effectively—do the necessary legwork to develop support for individual restaurateurs, retailers, hoteliers, local labor leaders and others.”[50] Significant local opposition to local ordinances was unlikely to exist without an employed coalition coordinator. While the industry was able to slow passage of local ordinances using these strategies, in the end the tobacco control community—through a combination of Proposition 99–funded educational programs and privately funded political action—was routinely defeating the tobacco industry at the local level.

An undated Philip Morris memorandum on various state tobacco control programs observed,

In California our biggest challenge has not been the anti-smoking advertising campaign created with cigarette excise tax dollars.

Rather, it has been the creation of an anti-smoking infrastructure, right down to the local level. It is an infrastructure that for the first time has the resources to tap into the anti-smoking network at the national level.[51] [emphasis added]

Much as it disliked the anti-tobacco media campaign, the industry recognized that, contrary to its early expectations, there were other potent forces at work that would cause serious problems.

The Tobacco Industry and the California Public Records Act

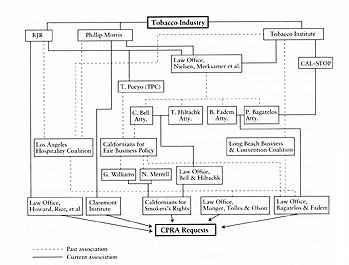

One final tactic strategically used by the tobacco industry to impede state and local tobacco control operations involved freedom of information

Figure 12. The tobacco industry's network of law firms and smokers' rights groups, which submitted requests to tobacco control organizations under the California Public Records Act. Source: S. Aguinaga and S.A. Glantz, The use of public records acts to interfere with tobacco control, Tobacco Control 1995;1995(4):222-230. Reproduced with permission of Tobacco Control (copyright BMJ Publishing Group).

DHS's Tobacco Control Section (TCS) received many more requests for public information than other seemingly controversial state-level health programs, such as AIDS and alcohol and drug programs or the HIV prevention program at the California Department of Education. In fact, TCS was the only health program receiving any requests; between 1991 and 1993, there were fifty-nine requests for 371 documents.[52] For example, on April 4, 1991, Mark Helm of the Los Angeles law firm Munger, Tolles & Olson wrote to the Tobacco Control Section to request

This tactic of using the freedom of information act as a form of harassment was to continue throughout the life of the program and eventually included requests to the health departments in the larger counties and the California Department of Education.[52] Program advocates, however, eventually understood how to handle such requests with minimal disruption to their operations: by requiring requests in writing and by assessing reasonable photocopying charges on the requesting parties.

Some of the LLAs responded to the requests by using them to call attention to the tobacco industry. In 1993, for example, the Contra Costa County LLA received a public records act request from a Marietta Stuart. The director replied by saying that complying with the request would disrupt the LLA's work and suggested that Stuart come in personally to inspect the documents and make photocopies. In response, the LLA received a call from the law firm Bell and Hiltachk, representing Californians for Smokers' Rights; the firm scheduled a time for someone to come with a copy machine to photocopy the documents. When Glenn Williams, a Californians for Smokers' Rights employee, arrived with a copier, the LLA director was waiting with the media to denounce what she perceived as harassment by pro-tobacco groups. The incident received wide coverage in the press, and requests to the LLA stopped.

The tobacco industry recognized that the public health community was getting more sophisticated in dealing with its tactics. For example, when Stratton, Reiter, Dupree & Durante was preparing its report for RJ Reynolds, one of the complaints in the report was the effectiveness with which TCS had dealt with records act requests: “TCS's heightened concern over the status of its '91-'92 Fiscal Budget, plus a profound screening process to ward off tobacco industry access to public documents, presented significant barriers to reviewing individual grants and county tobacco control plans. Thus a significant element of this research project involved creating access points to interviews and publications

Conclusion

The local battles of the late 1980s and early 1990s taught tobacco control advocates several lessons.[31][46] First, they could expect the tobacco industry to intervene, although indirectly, through groups like CBRA, SRMA, CFBP, and RSVP, to fight local tobacco control ordinances. Even these groups, however, tried to stay out of the public view by providing behind-the-scenes assistance and information to mobilize local opposition. Second, as the health dangers of secondhand smoke became more widely known and believed, the only way the industry could counter the health message was to generate claims of adverse economic impact. Since these claims were not sound, the tobacco industry had to create “facts” in order to make their arguments. Such facts were often generated and circulated by public affairs firms, particularly the claim that smoke-free ordinances had reduced restaurant sales by 30 percent. Local proponents learned to counter these “facts” with peer-reviewed scientific studies proving the industry charges of adverse economic consequences were not true. Third, while health professionals gained expertise in avoiding the time and expense of defending the ordinance at the polls, tobacco control advocates still had a chance to win if forced to the polls, in spite of the industry's money. In most cases, when tobacco control advocates and elected officials remained active and committed and raised adequate money, the industry's efforts failed. Effective campaigns took advantage of both the tobacco industry's lack of credibility and the voters' understanding of the dangers of secondhand smoke.

Proposition 99-funded education, through the media campaign, on the dangers of secondhand smoke, as well as the messages designed to discredit the tobacco industry, created an environment where it was easier to mobilize public and political support for policies to protect nonsmokers from secondhand smoke. The DHS also gave the Americans for

The tobacco industry recognized that its historical ability to control tobacco policy in California was no longer as effective because tobacco control advocates moved successfully to the local level and away from the Legislature. While they were willing to fight local ordinances as an interim measure, the industry was still counting on the California Legislature to rescue it, which it could do in two ways. First, the Legislature could increasingly “de-fund” the LLAs and the media campaign, both of which were supporting local efforts. Second, the Legislature could pass statewide legislation that would preempt the ability of local level governments, either city or county, to pass legislation.[59] With a single, weak state-level law, the local ordinance campaigns would disappear.

Notes

1. George Gallup. “Cancer Society given highest ratings in test of special interest groups” . Press release, April 16, 1989.

2. V. Lance Tarrance & Associates. “Kern County smoking study.” Houston, 1982 September.

3. Stumbo B. “Where there's smoke.” Los Angeles Times Magazine 1986 August 24:11-15.

4. Tobacco Institute, State Activities Division. “California: A multifaceted plan to address the negative environment.” Washington, DC. January 11, 1991. Bates No. 2023012755/2944.

5. Ifergan S-J, Milligan M. “Tobacco Institute acknowledges role in fight against B.H. no-smoke law.” Beverly Hills Courier 1987 April 24;3,10.

6. Arnold R. “Judge rejects challenge to Beverly Hills smoking ban.” Los Angeles Times 1987 April 3.

7. Hager P. “High court declines to review smoking ban in Beverly Hills.” Los Angeles Times 1987 May 21.

8. Ferris J. “Smoke screen clouds Tobacco Industry action.” Contra Costa Times 1991 June 23.

9. RJ Reynolds. “In the news.” Choice 1987;1(6):4.

10. Philip Morris USA. “The lessons of Beverly Hills.” Philip Morris Magazine 1991 Winter;6(1):22.

11. Philip Morris. Smoker 1988 July/August;1(6).

12. Fogel B. “Testimony before the New York City Council” . June 6, 1994.

13. US Environmental Protection Agency. “Respiratory health effects of passive smoking: Lung cancer and other disorders.” Washington, DC, 1992. USEPA Document No. EPA/600/6-90/006F.

14. Stoddard S. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. April 10, 1991” .

15. Samuels B, Glantz SA. “Tobacco control activities and the tobacco industry's response in California communities, 1990-1991.” San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. 1991 August.

16. Drummond M. “Council OKs smoking ban.” Lodi News Sentinel 1990 June 7.

17. Stamos B. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. November 14, 1990” .

18. Turner B. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. December 5, 1990” .

19. LICAC. “Campaign disclosure statement” . July 1-December 31, 1990.

20. Ross P. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. November 14, 1990” .

21. Ross P, St. Yves E. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. November 2, 1990” .

22. TUFF. “Ballot Measure Committee statements” . July 1-December 31, 1990.

23. Dados A. “Interview with Bruce Samuels. November 2, 1990” .

24. RJ Reynolds. “Independent Expenditure and Major Donor Committee campaign statement” . July 1-December 31, 1990.

25. Carol J. “Comments on manuscript” . October 1998.

26. Levin M. “Blowing smoke: Who's behind the building doctor.” The Nation 1993 August 9-16;168-171.

27. Mintz M. “Smokescreen / How the Tobacco Institute, its PR agents at Fleishman-Hillard and its lawyers at Covington & Burling helped turn a small-time Fairfax businessman into an international authority on indoor air quality and cigarette smoke.” Washington Post Magazine 1996 March 24;12-30.

28. Begay ME, Traynor MP, Glantz SA. “The twilight of Proposition 99: Reauthorization of tobacco education programs and tobacco industry expenditures in 1993.” San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1994 March.

29. Dempster D. “Bad news for smokers in capital.” Sacramento Bee 1990 September 12;A1.

30. Sacramentans for Fair Business Policy. “General Purpose Recipient Committee statements” . January 1-December 21, 1990.

31. Samuels B, Glantz S. “The politics of local tobacco control.” JAMA 1991;266(15):2110-2117.

32. Davilla R. “Smoking ban put on hold.” Sacramento Bee 1990 November 1.

33. Eagan T. “Memorandum to George Mimshew. September 20, 1990” . Bates No. 50764 0402/0405.

34. Smith M. “Memorandum to Tom Ogburn re: California update. April 17, 1991” . Bates No. 50770 3343-3344.

35. Woodruff T, Rosbrook B, Pierce J, Glantz S. “Lower levels of cigarette consumption found in smoke-free workplaces in California.” Archives of Internal Medicine 1993(153):1485-1493.

36. Glantz S. “Back to basics: Getting smoke-free workplaces back on track. Editorial.” Tobacco Control 1997;6:164-166.

37. McAdam RS. “Memorandum to Kurt L. Malmgren. November 27, 1991” . Bates Number TIMN 0022833/839.

38. Glantz SA, Smith LRA. “The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants on restaurant sales.” Am J Pub Health 1994;84:1081-1085.

39. Glantz SA, Smith LRA. “The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants and bars on revenues: A follow-up.” Am J Pub Health 1997;87:1687-1693.

40. Glantz SA, Smith L. “Erratum for “The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants and bars on revenues: A follow-up.”” Am J Pub Health 1998;88:1122.

41. Glantz SA. “Smokefree restaurant ordinances don't affect restaurant business. Period.” J Pub Health Management & Practice 1999;5:vi-ix.

42. Laufer D. “E-mail to Tina Walls re: San Fran. and CA. November 1, 1993” . Bates No. 2045891104.

43. Glantz SA, Smith LRA. “Erratum for “The effect of ordinances requiring smoke-free restaurants on restaurant sales.”” Am. J. Pub. Health 1997;87:1729-1730.

44. Price Waterhouse. “Potential economic effects of a smoking ban in the state of California.” N.p., 1993 May.

45. Tobacco Institute. “1992 referenda assessment. January 24, 1992” . Bates No. ATX03 0311555.

46. Traynor MP, Begay ME, Glantz SA. “New tobacco industry strategy to prevent local tobacco control.” JAMA 1993;270(4):479-486.

47. Morris RC. “Memorandum to Kent Rhodes re: Proactive opportunity, Placer County, California. April 25, 1991” . Bates No. TIMN 184603/184620.

48. J. Moore Methods. “Sacramento County smoking ordinance” . Sacramento: Citizens for Healthier Sacramento/Yes on G, 1992 January.

49. “Here comes the smoke.” Business Journal 1992 April 13.

50. Malmgren KL. “Memorandum to Samuel D. Chilcote, Jr., re: Expanded Local Program. November 30, 1992” . Bates No. 51333 1953/1965.

51. Philip Morris Tobacco. “Overview of state ASSIST programs. N.d. ” Bates No. 2021253353.

52. Aguinaga S, Glantz SA. “The use of public records acts to interfere with tobacco control.” Tobacco Control 1995;1995(4):222-230.

53. Helm MB. “Letter to California Department of Health Services. April 4, 1991.”

54. Newman FS. “Memo re: California anti-smoking advertising. June 8, 1990” . Bates No. 2022986403-6456.

55. Stratton, Reiter, Dupree & Durante. “Report to R. J. Reynolds Tobacco on the Tobacco Control Plan, State of California.” Denver, June 14, 1991. Bates No. 51319 3999/4061.

56. Pierce JP. “Evaluating Proposition 99 in California. Speech: American Heart Association, Nineteenth Science Writers Forum” . January 12-15, 1992.

57. Pierce JP, Evans N, Farkas AJ, Cavin SW, Berry C, Kramer M, Kealey S, Rosbrook B, Choi W, Kaplan RM.Tobacco use in California: An evaluation of the Tobacco Control Program, 1989-1993. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego, 1994.

58. Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, White M, Rosbrook B, Berry C. “Has the California Tobacco Control Program reduced smoking?” JAMA 1998;280(10).

59. Philip Morris (?). “1994 California Plan.” N.p., 1994. Bates No. 2022816070/6080.