7. Implementing the Tobacco Control Program

Despite the budgetary compromises that tobacco control advocates had made in AB 75, they still emerged with the largest budget ever allocated to a tobacco control program. The field of play shifted to the state bureaucracy, which had to implement California's Tobacco Control Program. While the Department of Health Services (DHS) ran the anti-tobacco media campaign and some competitive grants, the vast majority of the money flowed through DHS and the California Department of Education (CDE) to the county health departments, county offices of education, and local school districts. This program design meant that two state-level agencies, sixty-one local health departments, fifty-eight county offices of education, and over 1,000 school districts went overnight from having virtually no money dedicated to tobacco control to having over $100 million annually. The challenge for these organizations was to put into place immediately, with virtually no existing infrastructure, an unprecedented tobacco control program. Throughout the development and passage of Proposition 99 and the subsequent battle over the implementing legislation, there was a constant tension between those who wanted the money to go to programs specifically designed to reduce tobacco consumption and those who wanted to see the money go into health promotion generally, with the promise that there would be a tobacco control component.

In addition to active efforts by the tobacco industry to undermine the

Two Different Models

Although the voluntary health agencies had insisted that health education programs focus specifically on tobacco issues, the final legislation was permissive about what could be done with Proposition 99's Health Education Account money. According to the final language of AB 75, the agencies were to provide “preventative health education against tobacco use.” The bill broadly defined what such education might be. It included “programs of instruction intended to dissuade individuals from beginning to smoke, to encourage smoking cessation, or to provide information on the health effects of tobacco on the user, children, and nonsmokers. These programs may include a focus on health promotion, disease

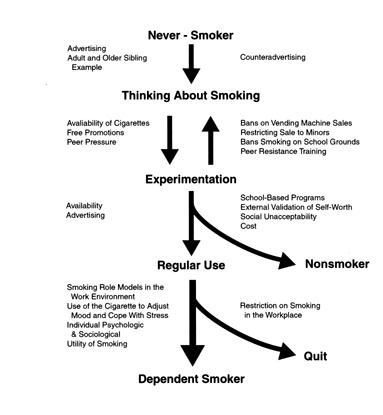

DHS chose to develop a tobacco-specific program based on a model for tobacco control developed at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).[2] According to this model, tobacco use, especially the adolescent progression to adult smoking, was the result of a specific and identifiable set of influences—including the tobacco industry's promotional activities (figure 6). The program sought to break the chain of events which led people to smoke or continue smoking. The NCI model guided program planners in designing tobacco interventions for delivery through four channels—health care settings, schools, community groups, and worksites—using one of three types of programs: mass media, policy, or direct program services. The first comprehensive plans from local health departments used a slightly modified version of this model.

In contrast, CDE simply incorporated the tobacco money into existing school-based programs designed to deal with the factors that put children “at risk” for using illegal drugs and alcohol.[3][4] In the “risk factor” approach, children who have problems in their own lives or with family, school, peers, or the community are considered at risk (figure 7). This approach seeks to enhance protective factors for these youth through the following specific activities:

- Promoting bonds to family, school, and positive peer groups through opportunities for active participation.

- Defining a clear set of tactics against drug use.

- Teaching the skills needed to learn the tactics.

- Providing recognition, rewards, and reinforcement for newly learned skills and behaviors.[5]

With the advent of Proposition 99, tobacco was added to this model because it was considered a “gateway” drug to the use of other drugs. CDE, citing data showing that youth tend to use drugs such as tobacco,

Figure 6. The National Cancer Institute's model of the factors influencing tobacco use. The model of tobacco uptake is linear and offers specific points of intervention. The DHS tobacco control program is based on this model. Source:National Institutes of Health, Strategies to control tobacco use in the United States: A blueprint for public health action in the 1990s (Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1991), 23.

alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs in a predictable sequence, concluded that “the nature of multi-drug use indicates that preventive efforts should not be targeted to any single drug.”[5]To curb the use of tobacco, along with other substance use, schools were urged to concentrate on alleviating the factors that put a child “at risk.”

Figure 7. The CDE risk and protective factors model of tobacco and substance abuse. The model is diffuse and does not offer specific intervention points that can be coordinated with community-based tobacco prevention programs. Source: California Department of Education, Not schools alone (Sacramento: California Deparment of Education, 1991), 2-3.

Leadership at DHS

The Department of Health Services is part of the State Health and Welfare Agency, which reports to the governor. At the time Proposition 99 passed, DHS was headed by Dr. Kenneth Kizer, who was personally committed to the success of the Proposition 99 programs and recognized

I can tell you in all candor that basically the approach that we took was one that we were going to try to do it right. …The Health Department took the position early on…that the Health Education Account should be used for health education, for media and local education campaigns, etc. That was not supported, or at least it didn't appear to be supported, strongly at the agency level. And it was absolutely not supported at the Governor's Office. …I think they [the Health and Welfare Agency] felt that was a huge amount of money…and there was no way that we could reasonably spend that in the time period.[7]

Kizer created a separate Tobacco Control Section (TCS) within DHS and ordered the administrative support units within DHS to give priority to staffing, issuing its requests for proposals, and adding other services needed to get the fledgling program up and running as quickly as possible.

TCS was to develop the state's anti-smoking media campaign and run a series of statewide projects and technical support activities as well as develop, fund, and oversee local tobacco control activities. The local activities were to be delivered and coordinated by local lead agencies (LLAs) in each of the California's sixty-one local health departments. Each LLA was designed to be an identifiable, tobacco-specific organization. This local structure, which was to emerge as one of the California Tobacco Control Program's greatest strengths, however, was relatively long in coming. TCS had to write guidelines for the local programs, the LLAs had to develop and submit plans, the plans had to be reviewed and approved, and the money distributed. And, of course, hundreds of people had to be recruited and trained to complete all these tasks, a process that took nearly a year.

The Media Campaign

In contrast to the complexities of getting the local programs off the ground, it was a relatively simple bureaucratic task to launch the anti-smoking media campaign that AB 75 had established. It merely required writing one request for proposals and issuing one contract to one advertising agency. It was the one way that DHS could show the public and politicians that it was doing something with Proposition 99 money in a hurry.

DHS moved quickly to implement the media campaign. The request for proposals was released on December 1, 1989, fifty-nine days after Governor Deukmejian had signed AB 75; responses from advertising agencies were due just six weeks later, on January 10, 1990. On January 26, DHS selected the Los Angeles advertising agency keye/donna/perlstein to run the campaign.[8] The first anti-tobacco advertisements reached California's television viewers on April 10, 1990, sixty-five days after the contract was signed.[9]

The campaign was like nothing the world had ever seen. Rather than talking about the dangers of smoking, or even secondhand smoke, the campaign directly and explicitly attacked the tobacco industry.

The first television advertisement, “Industry Spokesmen,” showed a group of actors portraying tobacco industry executives sitting around a smoke-filled room (figure 8). Their leader says:

Gentlemen, gentlemen. The tobacco industry has a very serious multi-billion-dollar problem. We need more cigarette smokers. Pure and simple. Every day, 2,000 Americans stop smoking and another 1,178 also quit. Actually, technically, they die.

That means that this business needs 3,000 fresh, new volunteers every day. So, forget all that cancer, heart disease, stroke stuff.

Gentlemen, we're not in this for our health.

At the end, he laughs, joined by the other executives.

This radical new approach grew out of discussions between Kizer, Dileep Bal, head of the Cancer Control Branch (which includes TCS), and ad agency principal Paul Keye, who brought a new perspective to the question of how to reduce tobacco consumption. As Keye later explained,

The cigarette companies were never in any of the advertising agency's original thoughts or conversations with the Department of Health Services. You can't find the topic in our first work. …What happened was that—as we dug into each topic—there, right in the middle of everything were the Smokefolk,

― 127 ―making their quaint, nonsensical arguments and—by sheer weight of wealth and power and privilege—getting away with it. …Frankly, the tobacco industry pissed us off. They insulted our intelligence.[10]

Figure 8. California's first anti-tobacco television advertisement, “Industry Spokesmen,” was a frontal attack on the tobacco industry. This advertisement set the tone for the California Tobacco Control Program when it was first aired in April 1990. (Courtesy California Department of Health Services)

Instead of falling back on the traditional public health messages (“tobacco is bad for you”), Keye urged that the campaign directly attack the tobacco industry. The first reaction to the campaign within TCS was surprise, with some wondering aloud, “Can we say that?” But TCS soon agreed that it could and should, and the anti-industry emphasis became an integral part of the campaign.[10][11] TCS was out to raise the temperature around tobacco as an issue, convincing people that smoking was not normal, ordinary behavior and the tobacco industry was not just another legal business.

To reinforce this message and to announce the new aggressive campaign against the tobacco industry, TCS ran full-page advertisements in all the major newspaper in California on April 11, 1990, with the headline “First, the Smoke. Now, the Mirrors”(figure 9). The text began:

In less than a generation, the bad news about cigarettes has become no news. Most Americans—even the very young—know the unavoidable connection

― 128 ―― 129 ―between smoking and cancer, smoking and heart disease, smoking and emphysema and strokes.Today a surprising number of us can tell you that cigarettes are our #1 preventable cause of death and disability.

So, we seem to know about the smoke. But what about the really dangerous stuff—all those carefully polished, fatal illusions the tobacco industry has crafted to mess with our minds so they can mess with our lives?[12]

Figure 9. California's first anti-tobacco newspaper advertisement. The Department of Health Services announced the new California Tobacco Control Program with this full-page advertisement in newspapers throughout the state on April 11, 1990. (Courtesy California Department of Health Services)

Smoking was not just a health problem; it was also a social and political one.

The tobacco industry and its allies in the advertising industry went wild. Walker Merryman, vice president for communications at the Tobacco Institute in Washington, protested that “the ads themselves have broken faith with the voters. …They are an unsavory assault on tobacco companies.” He claimed that they were not educational advertisements.[13] Tom Lauria, a spokesman for the Tobacco Institute, agreed: “They pitched Prop 99 as: `We want to reach underaged children. We want to educate children to the purported health effects of smoking.'…anything beyond that is not educational, it's political.”[14] Bob Garfield, a columnist in Advertising Age, an advertising industry trade newspaper, accused TCS of inciting racial paranoia by trading on “a vile stereotype: the wealthy, white embodiment of evil. …This `public service' message is inflammatory and racist and it will feed paranoia. …Californians should indeed be careful of what they breathe. There is something foul on their air.”[15]

Governor Deukmejian was cool toward the advertisements. One of his spokesmen explained: “It's not in the nature of the governor to go on an attack like this. He's always been genteel and civilized in his approach to public affairs.”[16] Deukmejian, however, took a hands-off approach to the campaign and allowed Kizer and DHS to proceed according to their professional judgment. Indeed, the Tobacco Institute lamented the way Governor Deukmejian was giving Kizer free rein over the campaign: “As a `lame duck,' the Governor is not likely to get into a public sparring match with Dr. Kizer, even though he disagrees with the Department of Health Services' attack approach with the anti-tobacco advertisements.”[17] Rather than submitting the detailed, multilayer political review of the media campaign that came to be required when Pete Wilson succeeded Deukmejian as governor, TCS simply made a “brown bag run” to the Governor's Office the night before new ads were aired so that the governor would know what was about to hit.

The other first-wave advertisements in 1990 were just as strong. One featured black rappers attacking the tobacco industry for targeting African Americans with mentholated cigarettes, using the tag line “We used to pick it; now they want us to smoke it.”[13] Another showed a husband and his pregnant wife sitting together. When the man lights up and inhales deeply, the smoke comes out the woman's mouth. The tag line was “Smokers aren't the only ones who smoke.”[15]

The advertisements attracted international attention. Indeed, in 1997, seven years after it had originally run and over a year after Governor Pete Wilson's administration had ordered it off the air permanently, “Industry Spokesmen” still had the highest recall rate—96 percent of adults and 93 percent of teens—of any advertisement that DHS produced.[18] The advertisements stimulated strong public interest in the Tobacco Control Program. They also set the overall tone for the program as one that considered tobacco a social and political problem well beyond the bounds of traditional public health thinking at the time.

The Local Lead Agencies

While the media campaign was jump-starting the Tobacco Control Program, the LLAs were still getting organized. In addition to the efforts within each local health department, each LLA was required to encourage the formation of a “local coalition” made up of players from the private and nonprofit sectors, including local units of the voluntary health agencies as well as new players in tobacco control. These local coalitions would play an increasingly important role in the evolution of California's Tobacco Control Program. The counties were required to submit preliminary plans in December 1989, before the media campaign had reached the public.

For most counties the tobacco revenue represented a substantial amount of new money, especially since Proposition 13 had hit the counties so hard. Each county received at least $150,000 a year, with the larger counties receiving considerably more: Los Angeles ($12.2 million), San Diego ($1.8 million), San Francisco ($1.6 million), and Santa Clara ($1.6 million). Even medium-sized counties like Ventura and Sonoma received over $460,000.[19]

TCS recognized that, in addition to guidelines, the LLAs needed a state infrastructure that would provide them with ongoing training and technical assistance. TCS hired a contractor to establish the Tobacco Education

Getting the LLAs off the ground, however, was a cumbersome process. Although Kizer had forced DHS to help TCS get up to speed quickly, most county tobacco control operations got no such special treatment. The slowness of county paper processing and the complex nature of county procedures impeded rapid program development. Part of the problem faced by one LLA director had to do with the unusual nature of her program design. She said, “The reality is no one had really had money like that to do anything innovative in the health department. So I think people had to get used to the idea of something different, including purchasing. I mean, you never had people buying some of the things we were buying before all this. Now they're used to it but it was unusual. …it took a lot of work, we had to go back two, three times sometimes.”[20] Eventually some LLAs cut back the number of grants to local groups for tobacco control work simply because of the time it took. On the other hand, some county administrators and politicians were important program advocates. Another LLA director described her

In contrast to the state level, the earliest local program designs reflected a traditional view of public health, focused on promoting smoking cessation, even though “policy” and “media” were part of the NCI model. But smoking cessation programs were comfortable. Most people who had trained in public health were familiar with providing direct services, especially cessation. The tobacco industry generally sits quietly when people run smoking cessation programs because such programs are expensive and not very effective. Generally only about 10 percent of those enrolled in cessation programs are still abstinent a year later, and cessation programs, because they approach smokers one person at a time, simply cannot reach a significant portion of the smoking population. Cessation programs do nothing to keep people from starting to smoke.

The media campaign was launched in the midst of the LLAs' efforts to get their programs up and running. Cynthia Hallett, then with the Los Angeles LLA, thought the advertisements were “great” but that they hit the streets almost too fast: “In trying to launch our education campaign, it was really difficult, given that media was out there and talking about how bad the tobacco industry was. And here we were just trying to start our program. People were calling us saying, `Those ads. Well, what are you guys doing? And can I get some service?' And we were still training staff.”[22] Whether intentional or not, the anti-industry focus of the media campaign began to shift the emphasis of the other programs toward policy interventions. In addition, Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights was continuing to support communities in developing and passing local tobacco control ordinances. ANR's policy-oriented approach already permeated the state and the LLAs felt its influence. Even so, it took a year or so to move beyond cessation programs to activities that would change the social environment enough to reduce tobacco consumption.

One LLA director commented that she moved into other programmatic areas almost immediately because she had done cessation before and did not want to do it again. But for most LLAs the transition to community-based strategies took longer. One LLA director described the process:

We ended up funding Stop Smoking and Smoking Prevention Programs for every ethnic group and every age group. We even had a preschool program. It was very much a cessation model, helping individuals quit smoking. People

― 133 ―thought that was the logical way to spend the money. …We had a Stop Smoking Program for the Vietnamese, another one for the Spanish-speaking. We had another one for African Americans. We had another one for senior citizens. We had one for teenagers. (laughter) I remember thinking, driving around one year later, “Is my program having any effect on this community?” Because everywhere I looked people were smoking inside and outside. I just had the sense that I was wasting public dollars.And meanwhile, people were calling me with bad secondhand smoke problems at their workplace. Totally bombarded. I would look up their [local clean indoor air] ordinance and say, “There is nothing I can do for you. Your employer can smoke at your workplace.” So the laws were very bad at that point. …So I remember driving down the street one day, thinking maybe we could just make everything smoke free.

So I talked to one of the higher-ups in the county, and said, “Why don't we just get a good county ordinance going here?” And she leaned over and she patted my hand and she said, “Oh no, dear, you don't know what you are talking about. This person on the Board [of Supervisors, the county legislative body] smokes, that person on the Board smokes. Their secretary smokes. Don't do it, don't even consider this.” So I said, “Well, OK, what if the cities passed ordinances and that would like peer-pressure the county into it?” And she kind of smiled. So I just hung in and got started, changed the whole program orientation to policy and ordinances.[23] [emphasis added]

This interest in doing policy work was not, however, universal. People worried about getting involved in local controversies and wanted to avoid confrontation with the tobacco industry and its political allies. People in public health departments who had trained as traditional health educators were not used to being confrontational or political. Their lack of experience was exacerbated by the ambivalence of coalitions consisting of other public health professionals or representatives of local units of the voluntary health agencies who were reluctant to get involved in politics.

Over time, however, the values and approaches of the Tobacco Control Program changed, and most program participants became more policy-oriented. In 1998, when asked what she would do differently if she had it to do over again, one of the reticent directors responded, “I would be more pro-active with local leaders. I would probably get into it, and say, `Oh well, if we're going to have a conflict, let's just go for it.'”[24]

Encouraging Diversity

Beginning with AB 75, tobacco control programs were required to focus on certain target populations, especially pregnant women, minorities, and youth. Public health groups viewed these subpopulations as important

Fortunately, TCS never interpreted this focus narrowly, and the result was a campaign that addressed the general population while including these groups. The effort to create an inclusive program brought a wide range of community-

For public health professionals working at the state and local level, it was a challenge to reach minority populations because health departments tended to be made up primarily of white, middle-class people. The LLAs addressed this problem by encouraging groups that were already working in the target communities to apply for LLA grants to fund tobacco control activities in those same communities. While this approach often worked, it ignored the need for capacity building around the tobacco issue. As a result, as the program evolved, the LLAs developed more directed strategies to involve these community groups. One county eventually created a “Tobacco 101” orientation that a group had to complete before they were eligible to receive grants from the health department. Eventually TCS also funded Ethnic Networks, which provided resources and networking capacity to community-based programs funded either directly by TCS or by the LLA to serve African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos on a statewide basis.[27]

As the thrust of the LLA programs began to shift away from cessation to community-based, policy-oriented work, the reliance on community-based organizations (CBOs) also meant that these groups had to be educated in the new paradigm and away from cessation classes. According to one LLA director, leaders of these community organizations often reacted skeptically: “`Why the hell should I be interested in this? I know that tobacco's bad, so what?' Moving them more toward looking at this issue globally, how does it impact them, what can they do about it. And again giving them the skills then to say, `Okay, now that I know that this is bad, what do I do?' Trying to get the CBOs to understand that they had to have an ongoing relationship with the community, to get them to understand why it's important to have smoke-free environments’ (emphasis added).[28] While there were difficulties in involving the new constituencies in tobacco control in California, community activities were to emerge as one of the strongest and most innovative aspects of the California Tobacco Control Program.

Peter Hanauer, a veteran of the Proposition 5, 10, and P campaigns, was impressed with the difference that this outreach made in the tobacco control movement:

Things had changed. I walked into a meeting in San Francisco,…this was sometime in the late eighties or early nineties, and I had been used to going to meetings with almost all white males, a few women occasionally, a token black occasionally. I walked into this meeting and it was like every spectrum of San Francisco society was represented there. …And I was overwhelmed when I walked in there and saw all of these people from all the different minority communities, who were up in arms because they had come to realize that the industry was preying on them, that the industry was not the good Samaritan that it pretended to be.[29]

While the original goal of involving community organizations had simply been to reach their constituencies with tobacco control messages, this effort was having much deeper effects. In particular, it was beginning to undermine the acceptance that the tobacco industry had built up over the years in these communities by providing financial support for community groups.

The effort to create diversity through grants, however, was more successful than creating diversity through volunteers. The LLAs were required by TCS to create a diverse coalition to help with their programs. But there were almost universal problems in trying to keep a coalition active and involved. In two of the fifteen counties where interviews were conducted, the coalition was an active body, involved in program design and local politics. Dynamic chairs from outside the LLA provided a great

TCS's push for coalitions brought mixed reactions from the LLAs, as did some of TCS's other actions. In the early days, life for the LLAs was chaotic, and people at the county level had mixed feelings about the TCS. In general, the directors of the larger, urban LLAs seemed to be happier with TCS than the smaller, rural ones. One LLA director from a large county made this comment:

They [TCS] were very, very supportive. And TCS has always been profoundly advanced in terms of policy, Carol Russell [who headed the local programs unit] especially. They could not have been better. They funded teleconferences through ANR [ANRF, American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation]. They had workshops directly. I mean, they just did everything they could; they understood early on how important this was. And they began to encourage us to move away from changing individual behavior more into the community norm and changing the environment.[23] [emphasis added]

Those working in the rural areas, however, felt from the beginning that the TCS program was not designed with them in mind. One blunt LLA director said,

They [the staff at TCS] are very controlling, very, very strong. …TCS has a very strong hand in what we do and what we don't do and how we do it. They want it on the paper in a certain way. They want us to do X, Y, Z and only X, Y, Z. And don't be interjecting any of your own creative problems into it. You do what you are told, you accept our money, and you play with our money within our realms. …They have no sense or feel [of] what is going to happen in a rural environment. We've never been asked by TCS, not to my knowledge have we ever been asked for input on what our areas of priority should be.[24]

A number of the rural LLA directors, when they were interviewed in 1998, were still stung by early accusations that they were racist when they protested that the targeted groups excluded the vast majority of their population, which was white.

The other major complaint from the rural areas had to do with the concentration of the media campaign in the major media markets. According to one LLA director, “When the media campaign was all over the state, that really was good, that was just so helpful and so beneficial. And then they started cutting down on…media coming up into this area, based on…population. …California does extend 300 miles north of Sacramento, and I was really indignant about [it] when they cut the media. And I still think it's a big loss to us.”[30] In another rural county, the LLA director wished that the advertisements at least existed in a format that could be shown in the local movie theater.[24] In general, there was a feeling that not a lot of creative thinking had gone into reaching the rural markets. This problem was aggravated by the dominance in some rural areas of out-of-state satellite television and other media.

Some of these tensions between the field and TCS would remain throughout

The Schools: A Different Approach

If it was a challenge for local health departments to build a mechanism for delivering tobacco control programs quickly, the schools faced an even greater problem. Every county had a health department, and those health departments had a tradition and mandate to do prevention-oriented activities directed at specific diseases or risks. Within schools, the situation was different. Health was not a central part of their mandate, and schools varied in their capacity to provide any kind of health education, much less something as specialized as tobacco use prevention. Moreover, teaching health issues of any kind in schools can expose the local elected board of education to controversy, which it may not be willing

From the beginning, the schools viewed the tobacco money as just another categorical program. Educators tend to resent categorical programs because they believe that such programs limit their authority to do what is best for their students and because the programs require excessive paperwork. Thus, while the Proposition 99 dollars were welcome, the mandate that the schools provide tobacco-specific prevention activities was not. In addition to these problems, AB 75's rapid sunset also caused difficulties. No one knew what would happen when AB 75's twenty-one months ran out, and this uncertain future made the schools even less interested in developing a long-term commitment to tobacco education.

When Proposition 99 passed, California schools were under financial siege. Proposition 13, which had limited the ability of local governments to raise local revenues, had hit the schools particularly hard. Bill Honig, who served as superintendent of public instruction when Proposition 99 passed and when AB 75 was being implemented, explained the situation this way:

There are four things that were going on in California that would make anything hard. Number one is this huge growth. Many places are just trying to accommodate new kids. …They're just coming out of the woodwork and we are not building the buildings. …Secondly, there has been this demographic shift of poverty. The explosive growth of poverty conditions makes schooling much tougher. More kids are coming with deep problems. Then the third one was this whole language demographic shift where you've got now, one out of three kids in that early elementary school level doesn't speak English. So we've got that problem. And then you have the funding crisis on top of that, we're trying to do it with less and less and less dollars.[32]

In this difficult climate, Proposition 99's new money was viewed by the schools as a way to solve some of their pressing problems.

At approximately the same time that Proposition 99 was passed, the California school superintendents were working to establish a regional structure to provide the school districts with health expertise. At the state level, CDE had already established a program and an administrative unit called Healthy Kids, Healthy California, which was responsible for carrying out health and drug-related programs. CDE decided to use the Healthy Kids Regional Centers to implement Proposition 99. CDE pooled the Proposition 99 monies with two other funding sources to

According to Kathy Yeates, who was the acting director of the Office of Healthy Kids, Healthy California in 1994, schools were not really committed to doing much about tobacco for a variety of reasons:

There was no commitment to it. It was like one more thing, given reading programs and bilingual and all the pressing problems—the obvious problems. “Yeah, some kids smoke, but who cares. You know, smoking. Big deal. …It's the least of our discipline problems right now. We've got kids fighting with guns; tobacco, that's just a passive problem. It's not as active as fighting or something like that.” A lot of school folks smoke and it was just too controversial with unions and whatever. So schools really didn't want to take it on. In addition to everybody having someone that's an alcoholic, everybody's got somebody in their families that smokes. And people on staff. …So they kind of tiptoed around it and didn't want to take it on. Didn't see it as a problem…as long as they weren't smoking in their classrooms, who cares what they do?…I mean like “Oh yeah, bad drugs,” but you know that's not the biggest problem.[33]

This attitude, coupled with the risk and protective factors model, provided schools with an opportunity to spend their Proposition 99 monies creatively. For schools, a program that addresses the problems that educators consider most pressing was much more appealing than taking on tobacco directly. From this perspective, if school failure is an underlying cause of tobacco use, then tobacco money could be spent on just about anything that would improve the schools.

The method used to distribute funds added to the problem. In contrast to the critical mass of funding created in the health departments, money went to the county offices of education and the school districts based on average daily student attendance. Once the money was spread over 1,003 districts, fifty-eight county offices, and ten regional centers, the amounts could be quite small. Some of the small districts received under $500, hardly enough to create an identifiable presence for tobacco control. By contrast, even the smallest county health department received $150,000. With a lack of commitment to Proposition 99 at the top, inadequate programming, and sometimes small amounts of money, it is not surprising that schools saw themselves as the recipients of a categorical funding stream, driven by entitlements, which they could try to use for

The poor condition of health education generally in California, due to years of Proposition 13-inspired budget cuts, created further problems for implementing meaningful tobacco prevention programs in the schools. (Increasing numbers of districts were cutting back or eliminating their school nurses at that time.) As one TUPE coordinator said, “All of this money has been flowing to schools with the assumption that there was an infrastructure in place for health education.”[34] The infrastructure to absorb this money and use it effectively simply did not exist. There is no high school graduation requirement for health education in California, and there is a very minimal requirement for health education in teacher credentialing. One of the county TUPE coordinators explained how the lack of infrastructure in schools set them up for failure, not just in tobacco programs but other health programs as well:

There wasn't an infrastructure there to accept the money. A lot of us were afraid that all this money was coming down and it was going to be misused because there wasn't anybody in place. This is kind of a Catch-22, it's a chicken-egg thing. We've got the money but nobody in place, so then we put the money in, we say, “Look, it's failing, it isn't working… .” This is the typical thing that's happened in health education in many instances where the person who ends up teaching it at the high school is the person who's on their last leg. “We don't know what to do with Charlie so we'll have him teach health.”[35]

The $36 million that schools were given each year during the two years of AB 75 would have been a substantial increment to an existing backbone for the delivery of health messages in the schools had it existed.

A coherent approach to tobacco education in the schools was further undermined by the absence of training, materials, or expertise in tobacco use prevention. This lack of materials reinforced the tendency of the schools to teach health as “body systems.” There was little in the way of good age-appropriate material that focused on tobacco as a social and political issue.

For early program implementers, CDE's lack of commitment to the program was reflected in the nature of its tobacco-free mandate. Schools were not required to have tobacco-free policies in order to qualify for Proposition 99 funds, and they were given until 1996 to become tobacco free. CDE promulgated a definition of “tobacco free” that was more rigorous than the definition used by other organizations—schools could not allow any smoking in the buildings, on the grounds (including service

Early Leadership Problems

It might have been possible to overcome the financial and structural problems that the schools faced in delivering anti-tobacco education if there had been strong and committed leadership at high levels within CDE, as Kizer had provided for DHS, but such leadership never materialized. Robert Ryan, who was the head of the Healthy Kids, Healthy California office and responsible for the anti-tobacco education efforts until he left in 1994, brought the right credentials to the job. With a background that combined training and education in both health and prevention, he had vision for the program, but his own drug and alcohol problems got the better of him and he quit coming to work.

Kathy Yeates, who worked with Ryan and his assistant Bill White (who headed CDE's tobacco program) and who was eventually named to succeed him, described the leadership problem:

Robert was already in big trouble with his own using of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. He was in big trouble. …I had told Robert that if he messed up one more time that I would have to do something about it, which I followed through and went…[to an] associate superintendent who went to the deputy and they just called him in and chewed him out. Nothing happened…so I watched Robert go downhill. …He hated confrontation of the mildest kind. And he just didn't come to work. …And it was too big of a task for the two of them to do without more competent staff. And they just didn't have additional competent staff that understood prevention. …And he didn't have the support of the agency, because he had jeopardized that. So he was taking all this flack—deserved, a lot of it deserved—but it was doing him in more than supporting him. So I think that he had the potential but he lost it. And the field was disenchanted. The CDE staff was disenchanted. And so because of that the program did suffer.[33]

At a conference in Millbrae, held in the spring of 1990, White told educators to put enough tobacco material in their drug programs so that if any parent was an executive at a local voluntary health agency, he or she would see something for the Proposition 99 dollars. Rather than encouraging schools to become a partner in the larger California Tobacco Control Program, the leadership appeared to be offering cash-strapped school districts a wink and a nod to use the money however they wanted.

Monitoring and Accountability

CDE's initial program simply involved distributing the money based on average daily attendance (ADA), with few program or fiscal guidelines. ADA-based funding is easier to distribute and is politically less volatile than a contract or grants program because it avoids the need to apply what some may consider subjective criteria. Distributing the money according to such a formula also means that no one has to consider the minimum amount of money that a small district needs to mount a credible program or the maximum that a large district can responsibly use.[36] (Severe understaffing at CDE—three people were charged with monitoring 1,003 school districts—aggravated this problem.) In addition, when funds are distributed on an ADA basis, monitoring the expenditures presents difficulties because districts receive an entitlement regardless of their interest in participating in the program.

Carolyn Martin, the first TEOC chair, was asked whether the accountability problems were the result of incompetence or a lack of interest in keeping track of the money. She replied, “I think it was both. I think that they were incompetent or they could have written much tighter guidelines for the schools. They full well knew that schools were in desperate shape for money, and, man, if they didn't ride herd on every penny, it was going to disappear. I mean you don't have to be a genius to figure this out. Nonetheless, the message that was sent out was `Do the best you can, guys.' Well, if you tell the schools to do the best you can,…believe me, the money will disappear. And indeed it did just go down a hole.”[37] Assembly Member Phil Isenberg (D-Sacramento), who chaired the Conference Committee that wrote AB 75, also became cynical about how schools were spending their money. He was invited to a celebration of Red Ribbon Week, an anti-drug program, during the 1989-1990 school year and was not happy to discover that the ribbons and balloons for the anti-drug week were purchased with tobacco funds. According to Isenberg, this incident inspired him to keep after the schools about their tobacco program:

They had this elaborate anti-drug program that was funded by the tobacco funds. And sure, did I mention that? Yes, I did. They were so pained because I probably mentioned it in at least three or four speeches. But nobody tried to take that money from them. On the other hand, it's pretty clear that health people don't control where the money goes once it reaches the schools. I mean it's just out there. It may be wonderfully spent, it may be well intentioned, but if the smoking rate of kids is any indication, it's not having…much impact.

― 143 ―…Once the money reaches the school site, nobody has much of an idea how it's spent or whether it does any good. And as we got into the latter years, and began to fumble around with performance information and outcome tests and so on, it reinforced again, the schools don't comfortably deal with that conceptually whether it's the cigarette tax money or anything else.[38]

Adding to the accountability problem of the blended model was the lack of a plan to evaluate program effectiveness. When asked about evaluation and reporting requirements at the first tobacco orientation conference held by CDE in San Diego in 1990, White simply told one TUPE coordinator, “Do the best you can.”[34]

CDE did not attempt to account for how the schools were spending the Proposition 99 Health Education Account until 1993, when it included use of these funds in its biennial Coordinated Compliance Review, whereby CDE evaluated how local districts were implementing state education mandates. The effort to put TUPE into the Coordinated Compliance Review reflects the effort under Yeates to give the program more accountability. By 1998, the inclusion of tobacco in the Coordinated Compliance Review was regarded as a help by virtually all of the county-level TUPE coordinators. According to one, “It took me a long time to come to this. I used to think if you just gave education the money and leave them alone, they will do the right thing. But I have learned that is not always the case.”[39]

Formalizing Noncooperation between DHS and the Schools

Even though it was theoretically desirable to have a close relationship between the DHS-funded community programs and the programs in the schools, there were many political and bureaucratic impediments to effective collaboration. The increasingly specific tobacco control programs of DHS, the LLAs, and their coalitions diverged over time from the schools' diffuse efforts. Tobacco control advocates increasingly viewed the schools as black holes into which money would disappear with little or no effect on tobacco consumption. TCS decided to limit LLA involvement in the classroom because of concern that the schools would coopt LLA funding to serve needs that CDE was supposed to be financing. TCS was also worried that, as with the early focus on cessation, LLAs would spend their time doing one-shot presentations in the schools rather than moving into policy-based activities for community change.

- DHS funds cannot be used for the development or implementation of in-classroom curriculum in public schools without prior state contract approval.

- DHS-funded programs in school settings must be non-curricular programs that supplement ongoing Department of Education (DOE) funded curriculum programs in the classroom or are extra-curricular activities for which DOE funding is not available to support.[40]

In 1993, in a study of eight counties, the three LLAs that were trying to collaborate with the schools voiced strong objections to the guidelines because the guidelines second-guessed and impeded their efforts.[41] By 1998, when fifteen of the sixty-one LLA directors were interviewed, no one mentioned them because most were no longer trying to work in schools very much.

Carolyn Martin, who headed TEOC at the time the classroom guidelines were established, was angry about them:

We found out later that, as the money became tighter, Dileep Bal had told his friends at DHS, “Under no circumstances are you to do anything whatsoever in the schools. They have their own money and we don't need to help them out.” Well, on the community level this is a source of great anger and resentment because it's stupid…and the local yokels know it. So we have absolutely given Dileep marching orders that they are to cooperate and spend time and money in the schools. Now whether or not that will happen, I don't know.[37]

The LLA directors had mixed reactions about the Proposition 99 program in the schools, generally more negative than positive. Of the fifteen LLA directors interviewed in 1998 for this book, seven thought that their schools had done very little on the tobacco issue. Five thought some tobacco programming had occurred, although they had hoped for better. Only three of the fifteen were supportive of the effort in their schools.

Conclusion

Thanks to the strong leadership that Ken Kizer showed at the Department of Health Services, the Proposition 99 program got up and running quickly. The media campaign was developed rapidly—so rapidly that it was on the air before the tobacco industry and its political allies could stop it. Rather than offering traditional anti-smoking messages, the media campaign set an aggressive tone that confronted the tobacco industry

In contrast, the schools failed to make effective use of the money to develop and implement specific programs for reducing tobacco use. The justification was based on a broader desire to reduce high-risk behavior among students, but the schools never produced convincing evidence that this program worked. This failure to develop effective tobacco control programs stemmed partly from the unique financial and political problems that the schools faced in post-Proposition 13 California and partly from a lack of leadership or even interest in tobacco control within CDE.

These two different approaches to spending the money that Proposition 99 made available were reflected in how these two communities reacted to potential controversy. The DHS programs often sought to create controversy as a way of engaging the public and increasing the visibility of the tobacco issue. The schools sought to avoid controversy. DHS sought to build a local network of people and institutions seeking to confront the tobacco industry and stimulate social change; the schools were trying to survive.

All the pressure was amplified by the size of the amount of money that Proposition 99 had suddenly made available and the knowledge that AB 75 would last only twenty-one months before the Legislature would have to pass a new law to continue authorizing the Proposition 99 programs. Joel Moskowitz, the project director for one of DHS's early evaluation contracts, observed, “The Legislature basically had set this whole thing up for failure anyway with the short enabling legislation. …When they passed AB 75, the word had gone out that this program was going to end with the demise of AB 75. The Legislature was going to rip off the money. I think that many people believed that, on the health side as well as the education side, the Legislature wasn't real serious about this program, just because of the short period of the enabling legislation.”[42]

Nearly two years before AB 75 passed, the health groups had originated the idea for a sunset provision in Senator Diane Watson's SB 2133 to ensure experimentation, evaluation, and accountability in the new programs

At the same time that tobacco control advocates were struggling to get the programs up and running and develop some idea of what worked and what did not work, the tobacco industry was already developing a sophisticated understanding of the damage that the media campaign and the local programs were doing and could do. The industry also recognized that the schools would not be a problem.

The fact that AB 75 would end only twenty-one months after it passed created unanticipated political problems for the people implementing the programs. It would take the Legislature several months to pass new authorizing legislation and additional time to launch the new Proposition 99 programs, which meant that proponents would be back in the Legislature debating the future of Proposition 99. This situation would create tremendous political problems for tobacco control advocates interested in defending the fledgling programs.

No one understood this reality better than the tobacco industry and its allies who wanted to see Health Education money diverted to medical services.

Notes

1. State of California, California State Legislature. “Assembly Bill 75. Sacramento, October 2, 1989” .

2. Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services. “National Cancer Institute Planning Model.” Sacramento, 1989 December.

3. Hawkins J, Jenson J, Catalano RJ. “Delinquency and drug abuse: Implications for social services” . Social Science Review 1988 June;258-284.

4. Hawkins J, Catalano R, Kaggerty K. “Risk and protective factors are interdependent” . Western Center News 1993 September.

5. California Department of Education. “Not Schools Alone. Sacramento, California Department of Education, 1991” .

6. Cook J. “Interview with Edith Balbach. March 19, 1998” .

7. Kizer K. “Interview with Michael Traynor. June 15, 1995” .

8. Lee P. “Keye/Donna to do anti-smoking ads for state” . Los Angeles Times 1990 January 27;D2.

9. “Scorching attack on cigarette firms” . Los Angeles Times 1990 April 10;1A.

10. Keye P. “What don't we know, and when haven't we known it? Speech given at Health Communications Day, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, October 13, 1993” .

11. Scott S. “Smoking out tobacco's influence” . Californian Journal 1997 April:14-18.

12. California Department of Health Services. “First the smoke. Now, the mirrors” . Newspaper advertisement, Sacramento Bee 1990 April 11.

13. Johnson B. “Anti-smoke torch flickers” . Advertising Age 1990 April 16;1.

14. Roan S. “State to launch anti-smoking ad campaign” . Los Angeles Times 1990 April 10;A1.

15. Garfield B. “California's anti-smoking ad fans flames of racial paranoia” . Advertising Age 1990 April 16;70.

16. Lucas G. “Deukmejian cool to blitz on smoking” . San Francisco Chronicle 1990 April 11;1.

17. Malmgren KL. “Memorandum to Samuel D. Chilcote, Jr. April 18, 1990” . Bates No. TIMN 298437/298420W.

18. Gallup Organization, Stanford University, University of Southern California. “Final report. Independent evaluation of the California Tobacco Control Prevention and Education Program: Wave 1 data, 1996-1997.” 1999 February.

19. Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services. “Local lead agencies. Sacramento, 1989” .

20. LLA Director 4. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1997” .

21. LLA Director 3. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

22. Hallett C. “Interview with Edith Balbach. March 27, 1998” .

23. LLA Director 6. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

24. LLA Director 1. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

25. Nielsen, Merksamer. “Memorandum to Executive Committee re: California state budget. December 15, 1988” . Bates No. 50763 7136/7160.

26. Glantz SA. “Preventing tobacco use—the youth access trap” . Am J Pub Health 1996;86(2):156-158.

27. LLA Director 9. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

28. LLA Director 5. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

29. Hanauer P. “Interview with Edith Balbach. June 4, 1998” .

30. LLA Director 2. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

31. Williamson J. “Statewide Projects Meeting minutes. May 7, 1993” .

32. Honig B. “Interview with Edith Balbach. January 4, 1994” .

33. Yeates K. “Interview with Edith Balbach. November 22, 1994” .

34. TUPE Coordinator 1. “Interview with Edith Balbach. Spring 1998” .

35. TUPE Coordinator 2. “Interview with Edith Balbach. Spring 1998” .

36. Wolfe G. “Interview with Edith Balbach. December 7, 1994” .

37. Martin C. “Interview with Edith Balbach. November 21, 1994” .

38. Isenberg P. “Interview with Edith Balbach. April 9, 1997” .

39. TUPE Coordinator 3. “Interview with Edith Balbach. Spring 1998” .

40. Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services. “ Comprehensive tobacco control guidelines for local lead agencies.” Sacramento, September 11, 1990.

41. Balbach ED. “Interagency Collaboration in the Delivery of the California Tobacco Education Program” [Ph.D.]. Berkeley: University of California at Berkeley, 1994.

42. Moskowitz J. “Interview with Edith Balbach. December 6, 1994” .