The Outcome

AB 75 appropriated a total of $272 million from the Health Education Account, which included the money raised from January 1, 1989, through June 30, 1991. The bill appropriated $978 million for indigent health care from the Physician Services Account, Hospital Services Account, and Unallocated Account for medical services. (A separate bill allocated $74 million from the Research Account for tobacco-related disease research; $74 million from the Public Resources Account was distributed through the budget for environmental protection.) The Child Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP) program was funded from the

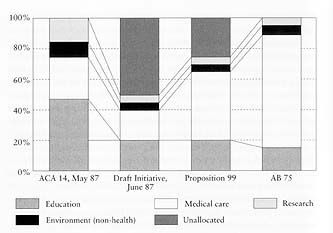

Figure 5. Tobacco tax revenue allocations for AB 75. The first implementing legislation for Proposition 99 appropriated more money for medical services than the initiative allowed and less for anti-tobacco education than it required.

Health Education Account, even though it was a medical service program. In total, AB 75 appropriated $1,017 million for medical services, or 69 percent of the total revenues available from the tobacco tax increase, including $96 million that the voters had earmarked for anti-tobacco education. AB 75 did not follow Proposition 99's directive that 20 percent of revenues be spent on anti-tobacco education (figure 5). For true anti-tobacco education it appropriated only $229 million, or 15.8 percent of total revenues.

The Health Education Account money was to target “high-risk populations,” particularly school-age youth and their families, blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, pregnant women, and current smokers. The money for local health department programs was allocated to “local lead agencies,” California's fifty-eight county health departments and three city health departments. Amounts were included in the 1989-1990 and 1990-1991 budgets to fund the competitive grants for other public and nonprofit agencies. School programs were to be administered by the California Department of Education (CDE), and money

AB 75 also established an eleven-member Tobacco Education Oversight Committee (TEOC), which was charged with advising DHS and CDE on programs funded by AB 75 and developing and updating the Master Plan. Members were to be appointed by the governor, the Senate Rules Committee, the speaker of the Assembly, and the superintendent of public instruction to represent specific constituencies, including voluntary health agencies, health care employees, university faculty, and target population groups. While TEOC was more limited in authority than originally envisioned by tobacco control advocates, they still hoped that TEOC would play an important role in guiding and evaluating the new program.

Throughout the development of AB 75, extending as far back as Watson's first proposal a year earlier (SB 2133), tobacco control advocates had recognized explicitly the experimental nature of the tobacco control program they sought to develop. In order to ensure accountability, they had included a sunset clause, requiring a return to the Legislature after two years to obtain new spending authorization. The idea behind this decision was to provide adequate oversight and adjustment for the new program during its developmental period. The sunset provision was incorporated into AB 75, requiring a new bill authorizing the Proposition 99 programs to be enacted by July 1, 1991. While this two-year period of initial experimentation seemed reasonable at the time, in fact only twenty-one months elapsed between the signing of AB 75 and the date when new legislation was required. Far from providing a more rational approach to developing the new program, the sunset provision was to create a new opportunity for the tobacco industry and its allies among the medical service providers to continue their efforts to divert Proposition 99 funds into “acceptable” programs.

AB 75 passed the Assembly by a 72-2 vote and the Senate by a 38-0 vote, and the governor signed it on October 2, 1989.