Getting the Medical Providers to Buy In

After repeated invitations, CAHHS representatives finally attended an October 1, 1987, meeting of the Coalition's Executive Committee. They expressed an interest in the initiative but raised concerns about its language and revenue allocations. The Executive Committee agreed that CAHHS, as a medical provider organization, should meet with the CMA to discuss the initiative language as well as the organization's involvement in the tax effort.

The Executive Committee recognized that the initiative had to amend the Gann Limit so that its spending provisions could withstand a legal challenge. To qualify a statute initiative for the ballot in California, supporters were required by state law to collect valid signatures amounting to 5 percent of the number of votes cast in the last gubernatorial election (372,178 valid signatures in this instance); but a constitutional amendment initiative, which was needed to address the Gann Limit, required signatures amounting to 8 percent of the votes cast in the last gubernatorial election, or 595,485 valid signatures.[10][11] Assuming a 65 percent validity rate, the Coalition had to collect over 915,000 raw signatures.

The need for extra funds as well as additional organizational and political support to collect the additional signatures was the main reason why the Executive Committee sought to enlist the participation of the CMA and CAHHS. The CMA was clear about its price for entry: it wanted more money for medical services. Carolyn Martin, a volunteer with the ALA who would play a leading role in the battles over Proposition 99, recalled the meeting years later: “My most vivid memory of the meeting was how shocked I was that the CMA proposed eliminating the Research Account completely and using the money for medical services. Since the American Lung Association includes the California Thoracic Society [a physicians' organization of lung specialists], I said, `absolutely not.' I couldn't believe doctors would oppose money for basic medical research on tobacco-related diseases! Yes, I was naive.”[12]

The CMA got its money.

According to the minutes of an October 26 meeting, the Executive Committee agreed to qualify a constitutional amendment and to allocate an additional 25 percent of tax revenues toward medical services in exchange for CMA and CAHHS participation and financial assistance to the tobacco tax effort. The minutes stated that “The Coalition is relying on pledges from CMA/CAHHS that between the two they can guarantee $250,000 in cash or signature equivalents and if they cannot make such guarantees in good conscience, they must tell us [the Executive Committee] so.”[13] Duane Dauner, president of CAHHS, and Fred Armstrong, president of CMA, accepted these conditions.

Unbeknownst to the participants at the October 26 meeting, however, the tobacco industry had already created procedural changes to return power to the “old guard” at the CMA and to neutralize Armstrong's authority on the initiative. The CMA had no intention of producing $250,000 in cash or signatures. In fact, when he was interviewed in 1993, CMA vice president and chief lobbyist Jay Michael did not remember that the CMA had made any commitments. He said, “I was the point person. If anyone would know, I would know, and I don't remember. I'm not sure we would ever say we would bring X amount. I don't think we ever did that.”[14]

In contrast to the CMA, CAHHS fully intended to keep its commitment and did so after finally deciding to get involved. According to Doug Hitchcock, the vice president and counsel for government relations at CAHHS, “We made a very heavy organizational commitment that we followed through on. And because we had done initiatives before, I think we brought some experience to the Coalition on ballot initiative campaigns. …Where hospitals were comfortable doing the signature-gathering campaign, they did signatures; where they weren't, they wrote a check, and most hospitals, as I recall, did some signature-gathering and then wrote a check for the balance of their commitment.”[15]

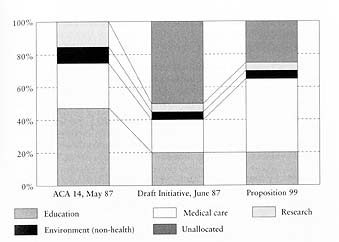

The new revenue allocation was not based on the results of the February 1987 Charlton Research poll, as ACA 14 had been, but rather on political and monetary considerations within the Coalition (figure 1). Funding for medical services was given higher priority than education and prevention. Medical services received the greatest share of revenues—45 percent—much more than the original legislative proposal of 27.5 percent. The allocation for education and prevention was reduced from 47.5 percent to 20 percent. The share for research was reduced from 15 percent to 5 percent. (The research money was given its own

Figure 1. Tobacco tax revenue allocations as Proposition 99 evolved. In order to attract support for the initiative, proponents moved money out of anti-tobacco education and research into medical services. ACA 14, the attempt to enact the tax through the Legislature, had more closely followed public opinion.