“Nicotine Soundbites”

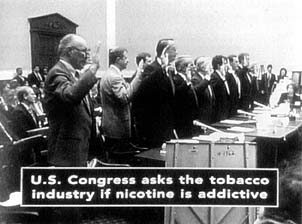

The funding cuts and slowdowns in producing new media materials were only some of the problems faced by the media campaign. The controls placed on the content of the media campaign were even more harmful. In 1994 TCS, working with its new advertising agency, Asher/Gould, produced a thirty-second television advertisement, “Nicotine Soundbites” (figure 22), that used actual footage from the landmark April 14, 1994, congressional hearing conducted by Representative Henry Waxman (D-California) at which the chief executives of the major cigarette companies denied that nicotine was addictive. The advertisement began with an image of the executives standing with their right hands raised swearing to tell the truth. Four of the executives, William Campbell of Philip Morris, James Johnston of RJ Reynolds, Thomas Sandefur of Brown and Williamson, and Donald Johnston of American Tobacco, all deny, each in turn, that nicotine is addictive as their names and companies flash on the screen. The advertisement ends with the question “Do they think we're stupid?” Public health advocates loved the advertisement and the tobacco industry went berserk.

Figure 22. “Nicotine Soundbites” television advertisement. DHS created the thirty-second ad from footage of the Waxman hearing. The ad showed tobacco industry executives stating, under oath, that they did not believe nicotine was addictive. The Wilson administration prohibited the airing of the ad after the tobacco industry complained. (Courtesy California Department of Health Services)

The advertisement was first aired on September 29, 1994. On October 6, lawyers for RJ Reynolds wrote DHS on behalf of the company's chief executive officer, James W. Johnston, claiming he was defamed and demanding an apology.[10] They also wrote to television station KABC in Hollywood, alleging that the advertisement was false and defamatory and demanding that the broadcasts end immediately.[11] They told Asher/Gould, “Your creation of an intentionally altered videotape is clearly outside the limits of legal or ethical behavior, and my client shall hold your agency, and everyone in this project, personally responsible.”[12] The lawyers demanded that Asher/Gould “set aside and preserve every document…in your possession or custody and control relating to the development, production, and distribution of the offending commercial.”[12] Finally, they demanded that DHS director S. Kimberly Belshé undertake “an immediate withdrawal of a television advertisement sponsored by your Department which contains a false and defamatory attack upon our client.”[13]

By October 17, 1994, KABC and two other television stations had pulled the advertisement off the air. Bruce Silverman, the president of Asher/Gould, had offered to indemnify several stations, including the Los Angeles NBC affiliate, to keep the advertisements on the air. According

Belshé publicly defended “Nicotine Soundbites” in a letter replying to Johnston's attorneys. She wrote,

This is to inform you that the Department of Health Services will not withdraw or alter the advertisement in question. Further, we adamantly deny any allegation of defamation resulting from this advertisement.…The point made by the ad, we believe, is that while individual industry executives may be able to make certain statements which are literally true in a narrow legal context, these statements do nothing to give credibility to the overall industry position that tobacco is not a harmful product.

Furthermore, I would like to take this opportunity to express my grave concerns regarding recent attempts which have been made to intervene in the airing of these ads by local television stations.[21]

“Nicotine Soundbites” remained on the air. But after DHS's public display of support, the administration quietly shelved it in early 1995.[22]

Beginning in 1995, the Wilson administration refused to air the spot, despite repeated requests to do so by public health advocates, including a formal request by the Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee (TEROC).[23] The administration's repeated excuse was a desire to avoid litigation (something it had no aversion to if the plaintiffs were the public health groups).[24] TEROC countered with a specific recommendation that it would endorse use of Health Education Account money to defend the advertisement in court, if necessary. Since “Nicotine Soundbites” was made up entirely of footage of the Waxman hearing, edited down to fit a thirty-second spot, and since truth is a defense, such litigation was extremely unlikely. Other states later aired the advertisement with no legal repercussions.

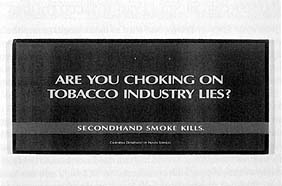

The content controls were not restricted to “Nicotine Soundbites.” In September 1994 Sandra Smoley personally intervened to remove 190 billboards bearing the message “Secondhand Smoke Kills: Are You Choking on Tobacco Industry Lies?” (figure 23). Smoley ordered that the billboards be papered over at a cost exceeding $10,000, even though Belshé had approved them. When her role became public because of materials that Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR) had obtained from DHS under the California Public Records Act, Smoley defended her position to the American Cancer Society (ACS), ANR, and the American Heart Association (AHA), saying that she ordered the billboard pulled because “it was found to be offensive for government to use taxpayer funds to call a private industry a liar” (emphasis added).[24] Smoley, a registered nurse, did not approve of accusing the tobacco industry of lying, despite the fact that accelerating litigation against the tobacco industry was revealing,

Figure 23. “Are You Choking on Tobacco Industry Lies?” billboard. Sandra Smoley, California's secretary of health and welfare, ordered DHS to paper over the billboards because she did not believe that it was appropriate to accuse the tobacco industry of lying. (Courtesy California Department of Health Services)

Smoley also killed the television advertisement “Insurance,” which pointed out that insurance companies owned by tobacco companies gave nonsmoker discounts and then asked the question “What do the tobacco guys know that they're not telling us?” She objected to an image of tobacco executives shredding documents. When the advertising agency offered to remove the few seconds of video showing the shredding, she still refused to allow the advertisement to be aired. In response to complaints by the public health groups about the administration's action, Smoley blamed them for raising the issue: “Your organizations have given unwarranted emphasis to the decision not to air an ad known as `Insurance.'…While the ad had much potential, and could have been aired with further work, DHS dropped the ad immediately after your press conference” (emphasis in original).[26] The state spent over $250,000 producing “Insurance,” only to leave the finished ad gathering dust on the shelf because the public health groups had asked where it was.