The End of the Diversions

The battle in 1996 was the last time that the governor or the Legislature tried to divert Proposition 99 money from the Health Education and Research Accounts into medical services. The 1997, 1998, and 1999 appropriations followed Proposition 99 and proceeded with little controversy (figure 19). This hands-off attitude is particularly interesting, given that the Court of Appeal eventually ruled in 1996 that SB 493, which expressly amended Proposition 99, might be legal and sent the issue back to the trial court for an evidentiary hearing. The Court of Appeal ruled that AB 816 was illegal because money from the Health Education and Research Accounts could not be used to fund medical services. In SB 493 the Legislature moved money out of the Health Education and Research Accounts into the medical service accounts and then appropriated the money. The Court of Appeal said that the plaintiffs had not put evidence into the record that demonstrated that this diversion of funds was “inconsistent with the purposes” of Proposition 99. This decision left the door open for further attempts at diversion, but the Legislature did not try.

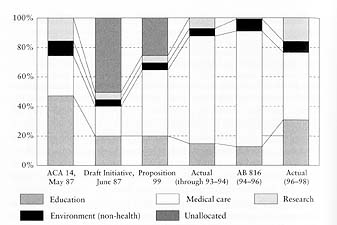

Figure 19. Tobacco tax revenue allocations, 1987-1998. The vigorous campaign mounted by health groups restored funding for the Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education and research programs starting with the 1996-1997 fiscal year.

The issue on SB 493 was that no evidence had been entered at the trial court level regarding the effects of the diversions on the Health Education and Research programs. If the existence of the programs had been jeopardized by the cuts, then the amendments were not consistent with the purposes of the initiative. On the other hand, if the programs were continuing to operate successfully, then the court was unsure that the diversions were, in fact, inconsistent with the purposes of the initiative. The Court of Appeal had no factual basis on which to make that decision. The voluntary health agencies and ANR appealed the SB 493 decision to the California Supreme Court, but the Supreme Court did not take the case, leaving the advocates with the decision whether to return to the trial court to introduce new evidence.

In the meantime, the $43 million that was being contested in court (see chapter 13) sat in reserve within the Health Education and Research Accounts. (The governor had spent the contested funds from AB 816 on anti-tobacco education and research after he lost the appeal, as well as about $22 million of the contested funds from SB 493.) In 1998, Glantz suggested to Van Maren that the Legislature simply appropriate this money for anti-tobacco education and research; in exchange, the health groups would drop their lawsuits. Senator Thompson and the Legislature agreed, and these funds were appropriated, which would have ended this litigation and provided more money for anti-tobacco education and research. Rather than concur with this resolution, however, Wilson used his line-item veto to scuttle the deal because Lee Sanders had refused to drop the SAYNO lawsuit over the AB 75 and AB 99 diversions.[61]