The Final Bill

The governor signed the bill, which contained cuts in anti-tobacco health education and research that were approximately what he had originally proposed (figure 15). Over the two fiscal years 1994-1995 and 1995-1996, AB 816 appropriated only $94 million for anti-tobacco education (as opposed to the $157 million required by the initiative) and $8 million for research (as opposed to the $44 million required by the initiative, plus the $21 million left unexpended from the previous year).[56] AB 816 brought the total amount of diversions from the Health Education and Research Accounts to medical services to $301 million since Proposition

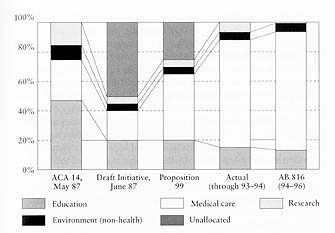

Figure 15. Proposition 99 funding allocations for AB 816. The legislation substantially accelerated the shift of money away from anti-tobacco education into medical services and now shifted funds from research too. It represented the most drastic diversion from the terms of Proposition 99 to date.

The outcome in 1994 thus continued the downward spiral for the Health Education and Research Accounts that began in 1989 with the first CHDP compromise. There was one important difference, however: in 1994 all three voluntary health agencies actively—if unsuccessfully—opposed any diversion from the Health Education and Research Accounts to fund medical services.

Assembly Member Terry Friedman (D-Santa Monica) abstained rather than voting against on AB 816.[43] A “no” vote would have deprived AB 816 of a four-fifths vote in the Assembly and stopped the diversions. In spite of all the work that the voluntary health agencies had done to pass his AB 13, which had barely made it through the Legislature in June 1994, Friedman did not support them on the AB 816 vote. Ironically, AB 13 was presented by some as an alternative to full funding of the Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education and research programs. For example, the Los Angeles Times editorialized in May 1994 that “the con

AB 816 contained three significant program changes. First, more controls were put on the schools. Schools would receive money based on Average Daily Attendance only for grades 4-8, while high schools would have to apply for competitive grants. In addition, evaluation of their programs would be conducted by evaluators in the DHS Tobacco Control Section (TCS), and the deadline for becoming tobacco free was moved from 1996 to 1995. Miller was less critical of Isenberg's stance on the schools than of his stance on the health departments and the Research Account. According to Miller, “The kinds of changes which had been proposed, indeed what Phil proposed for the schools, I think were long overdue and appropriate. I would still have an in-school program…[and] restrict it to those schools which express an interest.”[20] Second, public policy research was added as a priority area for the Research Account funding because it was “an area of compelling interest” to the Legislature. Third, the Tobacco Education Oversight Committee had oversight of the Research programs added to its mission and was renamed the Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee (TEROC). These changes were all consistent with positions the health groups had been advocating.

While the Health Education and Research Accounts took heavy hits from the Legislature, the governor's proposal to redirect some of the funds from the Public Resources Account was dropped, so this account again got more than its required minimum of 5 percent of the Proposition 99 dollars. According to Miller, the Legislature “gave about ten minutes to thinking about ripping off the mountain lion money and walked away from that” because “the environmentalists will kick their ass.”[9][20] The CMA's lobbyist, Elizabeth McNeil, had a similar response: “I think…fighting the environmentalists was a whole other realm, and a whole other fight, and I think that a lot of people made the assumption that that was a fight that was not even winnable. And that here was an arena where you had all health care organizations, who you could hope could help prioritize health care interests.”[7] There were important lessons here for the tobacco control advocates. The Public Resources Account was able to resist raids on its funds, and its advocates apparently had to do very little to protect it because everyone knew they were willing to “kick your ass.”