9—

Absalom, Absalom!:

A House Divided

In 1955 Faulkner published an article in Harper's Magazine entitled "On Privacy. The American Dream: What Happened to It." The article was part of an intended series of essays on American mores he planned in retaliation for repeated attempts by the press to publicize his personal life. The piece is a paean to the American dream as "a sanctuary on the earth for individual man: a condition in which he could be free not only of the old established closed-corporation hierarchies of arbitrary power which had oppressed him as a mass, but free of that mass into which the hierarchies of church and state had compressed and held him individually thralled and individually impotent."[1]

The first few pages review with similar rhetorical flamboyance the noble history of American individualism as epitomized in the hope of freedom to carve out a place in the world, make a home, and live in it in individual privacy, not as a part of the mass. He follows this sweeping manifesto with a story of several successful attempts to violate his privacy that were protected under the claim of freedom of the press, which "can postulate to itself complete immunity to violate the individualness—the individual privacy lacking which [one] cannot be an individual and lacking which individuality he is not anything at all worth the having or keeping" (68). His subsequent reflections on the misconstructions and misuses of American freedoms that threaten to turn the principles of freedom into instruments of oppression drive deep and close to the heart of the motivating vision that informs his fiction. Taste and responsibility as those humane qualities that temper the law are, he declares, all that distinguish liberty from license. He diagnoses the atrophy of these qualities as a sickness that "goes back to that moment when in place of freedom we substituted immunity for any

action to any recourse, provided merely that the act be performed beneath the aegis of the empty mouthsound of freedom" (69).

These distinctions—between freedom and license and between those with taste and responsibility and those without—are constants among the many dividing lines by which we can classify the characters who populate Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha—as diverse and tragic in their blind struggles over fate and freedom as the American types from which they are drawn. The figure of Thomas Sutpen looms as large as Captain Ahab's among literary portraits of American individualism turned to misguided ends, whose exercise of freedom becomes a form of violation and ends in the destruction of a grand design.

Sutpen's story, told and retold in Absalom, Absalom! starts and ends in urgent tête-à-têtes between storytellers who are makers and bearers of a legend bound to trace the path of the "magnificent defeat" of a grand design, its foundations weakened by pride:[2]

From a little after two o'clock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Cold-field still called the office because her father had called it that—a dim hot airless room with the blinds all closed and fastened for forty-three summers because when she was a girl someone had believed that light and moving air carried heat and that dark was always cooler, and which (as the sun shone fuller and fuller on that side of the house) became latticed with yellow slashes full of dust motes which Quentin thought of as being flecks of the dead old dried paint itself blown inward from the scaling blinds as wind might have blown them. (7)

On this first page of Absalom, Absalom! at what is for us the beginning of the story, though we are later to find that it is far from a beginning, young Quentin Compson sits captive, listening to the tale of the rise and fall of the house of Thomas Sutpen. Entrapped in the room, entrapped by the code of courtesy that keeps him there, entrapped by the tale itself, Quentin, like Miss Rosa, becomes a bearer of a legend that grows to occupy him to the point of obsession, as it has occupied her for forty-three years of her long, static, memory-ridden life.

The two characters seem at this moment suspended in time. As in a dream, the passage of actual time seems distorted. Pages, apparently hours, later Quentin observes, "It should have been later than it was; it should have been late, yet the yellow slashes of mote-palpitant sunlight were latticed no higher up the impalpable wall of gloom which separated them; the sun seemed hardly to have moved" (22). The story goes on and on, turning in on itself, as time stands still, caught with the light and the dust and the hot air in the small space of a dim hot airless room. Miss Rosa keeps the blinds closed despite the heat because of a notion someone once had and passed on to her that it is cooler that way. It is not. And herein we have our first clue to the character of Miss Rosa and to her relation to the immediate world. Quentin watches flecks of paint dancing in the light beams borne on an imaginary wind. But they are not flecks of paint, and there is no wind. And herein we have our first clue to how Quentin sees.

Miss Rosa has summoned Quentin to tell him the story of Thomas Sutpen, to pour it into him as into a receptacle, to transmit responsibility for it to him and there by rid herself of the obsession that has consumed her for four bitter decades. She has cast herself as chronicler and guardian of local legend, a sibyl waiting out her time, condemned to endless remembering and rehearsing of events that, having witnessed, she is compelled to prophesy. Sutpen's story has become her fate as, in a larger sense, it has become a local creation myth, a prototypical and paradigmatic story of the South. Entrusting this story with its mysteries and undisclosed secrets to Quentin imposes on him a burden of manifold obligations that he only begins to divine as he sits spellbound, a half-willing listener. She begins at the beginning, with the mysterious and portentous arrival of Thomas Sutpen and his entourage in Jefferson in 1833:

A man who rode into town out of nowhere with a horse and two pistols and a herd of wild beasts that he had hunted down singlehanded because he was stronger in fear than even they were in whatever heathen place he had fled from, and that French architect who looked like he had been hunted down and caught in turn by the negroes—a man who fled here and hid, concealed himself behind respectability, behind that hundred miles of land which he

took from a tribe of ignorant Indians, nobody knows how, and a house the size of a courthouse where he lived for three years without a window or door or bedstead in it and still called it Sutpen's Hundred as if it had been a king's grant in unbroken perpetuity from his great grandfather—a home, position: a wife and family which, being necessary to concealment, he accepted along with the rest of respectability as he would have accepted the necessary discomfort and even pain of the briers and thorns in a thicket if the thicket could have given him the protection he sought. (16)

In one sentence, Miss Rosa provides the "fable" that unfolds in all its convoluted complexities in the following three hundred pages: the story of the rise and fall of the house of Sutpen—a recasting of the tale of creation, the fall, and its consequences or, as many readers have recognized, a recasting of American history with its grand, theocratic designs; its tragic divisions; and its degeneration by greed, miscegenation, and violence. Indictment and judgment as well as the insight of one who knows intimately of whom she speaks are implied in her words: "strong in fear," "concealed himself behind respectability," "the protection he sought." This is a story of a usurper who has seized illicitly the inheritance of the sons and built an empire on a wrongful claim. Miss Rosa's telling begins a long project of reconstruction; she rebuilds the house of Sutpen in words of her own, taking possession of his house and land by the power of the spoken word. Like a haunted prophet crying, "Set down this, set down this," she enjoins Quentin to inscribe the story in writing and take it abroad and sell it. The long trajectory of building and destruction will then be complete: an idea bodied forth in house and formal gardens and sprawling plantation, passed from hand to hand, sold piecemeal, diminished, and finally burned, becomes a story to be written and sold for money, she suggests, that might serve to furnish Quentin's own house someday.

In the little dark room where we first see them, the old woman and the young man sitting opposite each other resemble a medium with her half-willing client, summoning a ghost from the dead. The spirit of Thomas Sutpen inhabits the story, the room, the woman. As she unravels the long tale, her little dried legs swinging beneath her chair, Quentin, listening, dis-

cerns an alien presence evoked by her monotonous recitation: "The ghost mused with shadowy docility as if it were the voice which he haunted where a more fortunate one would have had a house" (8).

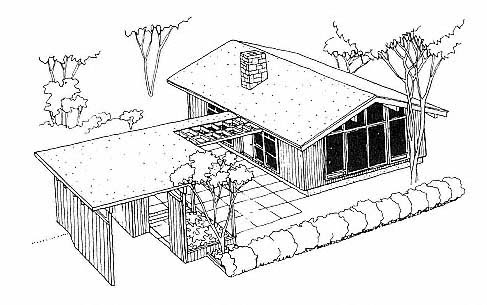

Thomas Sutpen did have a house, one "torn violently" out of the wilderness, built on stolen land, by a man who "came from nowhere" and was of unknown origin and pedigree. At its most literal Absalom, Absalom! is the story of that house—a story of expropriation, settlement, empire-building, destruction, and dubious hope of reconstruction on questionable terms. Like Poe's house of Usher, the house, the structure at the center of this novel, is symbolically reiterated in every element of the story, indeed in the circuitous, symmetrical, and secretive design of the story itself, and reveals itself as the shape of a universe, its design a caricature of southern life, its fate the fate of a people.[3]

Each of the four narrators, Miss Rosa, Quentin, Quentin's father, and Shreve, attempts to reconstruct from fragmentary and elusive data some lost and irrecoverable vision incarnated in the house of Sutpen. Miss Rosa is driven by revenge; Quentin, by a sense of inherited obligation; Mr. Compson, by a historical and legal interest in facts; Shreve, by the fascination of the Other. Like Sutpen with his grand design, each is pursuing a vision of something that, when attained, will have the completeness and inevitability of revelation. The ultimate "narrator" is the reader, who, like them, is involved in piecing together conflicting and fragmentary stories to achieve a moment of whole sight. Like the image in a kaleidoscope, the story keeps shifting, tantalizingly redistributing its discrete elements in new and intriguing but unstable patterns of meaning. Characters, narrators, and the narrative itself are comprehensible only as functions of labyrinthine cultural, legal, familial, psychic, and linguistic structures as deceptive and illusory as Sutpen's great "shell" of a mansion, whose purpose was defeated in the very act of building. If it were a simple moral tale, the moral of Sutpen's story might be that all efforts to impose structure on chaos and conquer the wilderness ultimately fail, that the enterprise of civilization is doomed because all our endeavors to raise up our houses and lives out of the primordial mud are built on

falsehood and crumble to dust in our wake. Yet even as a story of defeat, the magnificence of the design and the courage, audacity, and even presumption of the builder are portrayed in heroic terms, and the story of the house of Sutpen is a tragedy of classic dimensions.

Quentin measures Miss Rosa's bitter story of how Sutpen seized his land and built his house against the more dispassionate, or at least more sympathetic, account he has received from his father, who received it from his father, who described to him how the suspicious and apprehensive citizens of Jefferson watched the invasion and transformation of their countryside:

As General Compson told his son, Quentin's father, while the negroes were working Sutpen never raised his voice at them, that instead he led them, caught them at the psychological instant by example, by some ascendancy of forbearance rather than by brute fear. Without dismounting (usually Sutpen did not even greet them with as much as a nod, apparently as unaware of their presence as if they had been idle shades) they would sit in a curious quiet clump as though for mutual protection and watch his mansion rise, carried plank by plank and brick by brick out of the swamp where the clay and timber waited—the bearded white man and the twenty black ones and all stark naked beneath the croaching and pervading mud. (37)

The respect in this portrayal contrasts sharply with the tone of Miss Rosa's description of the same events:

So he and the twenty negroes worked together, plastered over with mud against the mosquitoes and . . . distinguishable from one another by his beard and eyes alone and only the architect resembling a human creature . . . working in the sun and heat of summer and the mud and ice of winter, with quiet and unflagging fury. (38)

The problem here and throughout for Quentin, and for us, is how to interpret the paradoxical unorthodoxies by which Sutpen disturbs the universe of Yoknapatawpha county and threatens the locals' sense of fundamental proprieties.

The ambiguity of Sutpen's character and the nature of his errand in the wilderness are complicated for the reader by the dissonance among the various narrators' accounts. As Quentin

conceives it, the building of Sutpen's house is at its very inception an act of violence and presumption, not unlike the satanic will to "be as God" implied in the story of the original sin. Sutpen appears as a creature not fully human, emerging out of "no discernible past," of dubious origins and with dubious and alien servants to expropriate land that was neither granted nor sold him, wreaking his will on it, building a house "apparently out of nothing"—a repeated phrase that suggests a preternatural dimension in these events.

Out of quiet thunderclap he would abrupt (man-horse-demon) upon a scene peaceful and decorous as a schoolprize water color, faint sulphur-reek still in hair clothes and beard, with grouped behind him his band of wild niggers like beasts half tamed to walk upright like men, in attitudes wild and reposed, and manacled among them the French architect with his air grim, haggard, and tatter-ran. Immobile, bearded and hand palm-lifted the horseman sat; behind him the wild blacks and the captive architect huddled quietly, carrying in bloodless paradox the shovels and picks and axes of peaceful conquest. Then in the long unmaze Quentin seemed to watch them overrun suddenly the hundred square miles of tranquil and astonished earth and drag house and formal gardens violently out of the soundless Nothing and clap them down like cards upon a table beneath the up-palm immobile and pontific, creating the Sutpen's Hundred, the Be Sutpen's Hundred like the oldentime Be Light . (8–9)

This remarkable passage gives us Sutpen as a demon-god and the house as a monument to the magnitude of a usurper's presumption. The "man-horse-demon" hybrid conjures a pagan image of a centaur or other weird half-breed that straddles a boundary between two discrete orders of being. The sulphur-reek suggests hell; the slaves with him are alien and hybrid creatures, paradoxical, too, in their "wild repose."

Thomas, the twin, the dubious disciple, author of an apocryphal and rejected gospel: much can be read into the name chosen for this elusive figure who can be reached only by speculation. And the name of Sutpen hovers close to the name of Satan, who in his defiance disrupted the divine order to establish "death's other kingdom." Miss Rosa observes, "He wasn't even a gentleman. He came here with a horse and two pistols

and a name which nobody ever heard before, knew for certain was his own anymore than the horse was his own or even the pistols, seeking some place to hide himself, and Yoknapatawpha County supplied him with it" (3). The fugitive who claims the land he is banished to and makes it his kingdom threatens not only the inhabitants of the land but the whole existing order. The dispossessed who takes possession is the archetypal American, guilty and triumphant in his self-proclaimed entitlement.

The figure of Sutpen, "immobile, bearded and hand palm-lifted" on his horse bears, however, a shocking similarity to the figure of God the Father in medieval paintings, static, flat, hand lifted eternally in blessing over the riotous earth. The only verb in this passage that describes Sutpen's movement is "abrupt"—an adjective pressed into service to connote action, not movement so much as the sudden apparition of a ghost moving neither from nor toward but breaking through some invisible barrier that separates orders of existence. In every respect this passage gives us Sutpen as a preternatural figure.

In a shift we come to recognize as a characteristic modulation from one plane of story to another, the narrator moves beyond Miss Rosa's actual description into Quentin's private elaboration of it: "Then in the long unamaze Quentin seemed to watch them." The figures and action become more and more archetypal and stylized as they pass from her memory to his imagination. In Quentin's version the scene broadens from portraiture to landscape, and a sudden moment in time becomes an epoch as the invaders "overrun" the "hundred square miles of tranquil and astonished earth." The scene becomes mythic and epic as Quentin "watches" Sutpen's hordes "drag house and formal gardens violently out of the soundless Nothing and clap them down like cards on a table beneath the up-palm immobile and pontific" and concludes with a final vision of Sutpen as God, creating his own order out of Nothingness by simple command. The house and formal gardens signify establishment of order in the wilderness.

The image of cards on a table, however, strikes an insidious note in this creation myth; the gesture is a gamble, the gambler a careless and violent man, the house a gesture of, what? defiance? presumption? challenge? in any case the signature of one

whose claim and character are open to dispute, though his power is not. Quentin, rehearsing the story to himself, embroidering on it as he listens, reflects, "Who came out of nowhere and without warning on the land with a band of strange niggers and built a plantation—(Tore violently a plantation, Miss Rosa Coldfield says)—tore violently" (9). Pausing over the verb in this way underscores the paradox of building that is also destroying, amounting to a rape of nature, surprised and violated like a woman forced to suffer the attacks and bear the child of a stranger. The house, in this light, becomes something monstrous and unnatural, not an extension of the natural setting but a scar on it.

As the final sentence implies, the erection of this house represents an order wrenched out of proper context. The men who build it are dark, captive men, portrayed as beings of a lower order, except for the curious French architect whose ambivalent presence and eventual escape suggest Sutpen's limitations. Sutpen needs the aid of this foreign and civilized intelligence to carry out his plan. He cannot himself civilize this wilderness because he is himself of the wilderness, so he attempts to turn the forces of civilization to his own primitive purposes.

The figure of the French architect adds a comic element to what might otherwise be a solemn reiteration of the Edenic myth. The incidental characterization of Sutpen's mansion in Requiem for a Nun as "something like a wing of Versailles glimpsed in a Lilliput's Gothic nightmare" suggests, William Ruzicka points out, "the presence of French Baroque details in the stylistic vocabulary of the house, provides a reference for conjecturing overall dimensions, and recommends certain images of grandeur and scale."[4] The allusion furthermore calls up images of baroque garden-palaces in which a "world" is divided in half and the sovereign is situated at the center; this allusion therefore highlights the magnitude of Sutpen's pretensions and caricatures them in the pathetic figure of the architect.

The ambiguous nature of Sutpen's achievement is represented most vividly in the comic contrast between him and his captive French architect, a poignant Chaplinesque figure in whose person the remnants of civilized gentility are diminished and pathetic, dwarfed in the shadow of Sutpen's primal,

mud-covered body, yet whose education and expertise are necessary to the completion of his scheme. Quentin's father describes the architect as

a small, alertly resigned man with a grim, harried Latin face, in a frock coat and a flowered waistcoat and a hat which would have created no furore on a Paris boulevard, all of which he was to wear constantly for the next two years—the somberly theatric clothing and the expression of fatalistic and amazed determination—while his white client and the negro crew which he was to advise though not direct went stark naked save for a coating of dried mud. This was the French architect. Years later the town learned that he had come all the way from Martinique on Sutpen's bare promise and lived for two years on venison cooked over a campfire, in an un-floored tent made of the wagon hood, before he so much as saw any color or shape of pay. (35)

A later addendum to this portrait details the architect's confused role in Sutpen's project:

They worked from sunup to sundown while . . . the architect in his formal coat and his Paris hat and his expression of grim and embittered amazement lurked about the environs of the scene with his air something between a casual and bitterly disinterested spectator and a condemned and conscientious ghost—amazement, General Compson said, not at the others and what they were doing so much as at himself, at the inexplicable and incredible fact of his own presence. (39)

But Quentin measures this parodic characterization against the evidence of something more substantial, a contribution more essential and significant than these comic vignettes seem to imply:

He was a good architect; Quentin knew the house, twelve miles from Jefferson, in its grove of cedar and oak, seventy-five years after it was finished. And not only an architect, as General Compson said, but an artist since only an artist could have borne those two years in order to build a house which he doubtless not only expected but firmly intended never to see again. . . . That only an artist could have borne Sutpen's ruthlessness and hurry and still manage to curb the dream of grim and castlelike magnificence at

which Sutpen obviously aimed, since the place as Sutpen planned it would have been almost as large as Jefferson itself at the time; that the little grim harried foreigner had singlehanded given battle to and vanquished Sutpen's fierce and overweening vanity or desire for magnificence or for vindication or whatever it was . . . and so created of Sutpen's very defeat the victory which, in conquering, Sutpen himself would have failed to gain. (39)

In his tattered finery, huddled on a wagon among a throng of "half-naked savages," the architect embodies a number of paradoxes: he represents the cumulative knowledge and culture of European civilization that the settlers of this American wilderness both scorn and depend on. Though he provides the requisite expertise for Sutpen to carry out his plan, the architect's authority and status remain unacknowledged, and in fact he becomes an object of contempt to the very man who depends on him to establish a kingdom in the wilderness. It is the architect who exercises the curbing force by which Sutpen would destroy himself, who tempers and refines and controls. He is the force of civilization: seasoned and tolerant and steeped in compromise. He is the hidden intelligence behind the mythic silhouette of Thomas Sutpen, the conquering hero and claimant to this fated land. As such the architect's presence belies the mythic notion of Sutpen as a demigod who emerged out of nothing and nowhere. The Frenchman brings Sutpen down to size, gives him human dimensions, and, as Sutpen's complement and counterpart, throws into relief Sutpen's limitations and excesses.

At one point Miss Rosa describes the architect as a man "who looked like he had been hunted down and caught in turn by the negroes" (16). Like Europeans terrified of "going native" among primitive peoples, the high culture the architect represents cannot survive the conditions of the American wilderness. His final escape, abandoning the savage master and his wild band to their own devices, signals the end of the period of design and construction and the beginning of the long saga of degeneration and destruction. Quentin describes that escape in provocative terms when he recreates the scene for Shreve:

and [Sutpen] got his dogs and his wild niggers out and hunted the architect down and made him take earth in a cave under the river bank two days later. That was in the second summer, when they had finished all the brick and had the foundations laid and most of the big timbers cut and trimmed, and one day the architect couldn't stand it anymore or he was afraid he would starve or that the wild niggers (and maybe Colonel Sutpen too) would run out of grub and eat him or maybe he got homesick or maybe he just had to go. . . . So I reckon the niggers never did know what the architect was there for, supposed to do or had done or could do or was, so maybe they thought Sutpen had sent him, told him to go away and drown himself, go away and die, or maybe just go away. (219)

The speculations progressively trivialize the architect's purpose and fate, reducing him to pathetic insignificance. When the architect leaves, Sutpen in fact celebrates by declaring a holiday from work on the house: "And Grandfather . . . brought some champagne and some of the others brought whiskey and they began to gather out there a little after sundown, at Sutpen's house that didn't even have walls yet, that wasn't anything yet but some lines of bricks into the ground but that was all right because they didn't go to bed anyhow" (219). The bacchanalian scene not only signals a temporary cessation of labor, however; the departure of the architect, leaving Sutpen to his own inscrutable and idiosyncratic devices, represents the end of the period of controlled and methodical building. In a kind of inverted banishment from Eden, this departure is the beginning of a new and ominous chapter in the Sutpen saga. The nearly finished house remains in a curiously unfinished state, as if the subtleties of civilizing detail are beyond Sutpen's ken, and the master lives in the house in inappropriate primitive simplicity:

So it was finished then, down to the last plank and brick and wooden pin which they could make themselves. Unpainted and unfurnished, without a pane of glass or a doorknob or hinge in it, twelve miles from town and almost that far from any neighbor, it stood for three years more surrounded by its formal gardens and promenades, its slave quarters and stables and smokehouses; wild turkey ranged within a mile of the house and deer came light and

colored like smoke and left delicate prints in the formal beds where there would be no flowers for four years yet. (39)

Miss Rosa's judgment is that Sutpen had "builded even better in evil than he could have hoped" (30). His master plan, his grand design, his scheme to claim and populate his square of earth, was indisputably magnificent but for a fatal hubris running through every aspect of it like a disease in the blood. She remembers the period of desperate completion when the seeds of Sutpen's own destruction began to flower almost before his house was a habitation: "Because the town now believed that it knew him. For two years it had watched him as with that grim and unflagging fury he had erected that shell of a house and laid out his fields, then for three years he had remained completely static, as if he were run by electricity and someone had come along and removed, dismantled the wiring or the dynamo" (42).

At the end of those three years of primitive solitude, Sutpen went after a wife, as part of his plan, in a similarly calculated and inhuman way: "He had apparently marked down Miss Coldfield's father with the same cold and ruthless deliberation with which he had probably marked down the French architect" (42). But at this stage no one could name the evil he was wreaking. On the face of things, for a man to build a house and court a wife might seem eminently natural and right. Yet for Sutpen to engage in these rituals invested them with a sinister significance no one at the time was able to explain because they proceeded out of a state of "ontological poverty"—an incapacity to sense or assign meaning or to care for and enjoy the things he possessed. Building and creating served essentially egotistical, imperialistic ends.[5]

No one could specify what crime he had committed, perhaps because the scope of the crime was beyond the law itself. As Quentin's father reflects, "Heretofore, until that Sunday when he came to church, if he had misused or injured anybody, it was only old Ikkemotubbe, from whom he got his land—a matter between his conscience and Uncle Sam and God" (44), a matter of justice beyond the jurisdiction of existing laws and

perhaps even outside the scope of contemporary conscience. But that Sunday, when he came to church to court his bride, the town began to watch his deceptively conventional enactment of the rituals of domestication with a deepening sense of foreboding: "They just waited while reports and rumors came back to town of how he and his now somewhat tamed negroes had installed the windows and doors and the spits and pots in the kitchen and the crystal chandeliers in the parlors and the furniture and the curtains and the rugs" (44). To Quentin, Miss Rosa recounts this scene of preparation as the laying of a trap for Ellen, her sister, the innocent bride Sutpen was to drive to distraction and death by his monomaniacal plans, in which she figured only as a functionary, a necessary piece of the furniture of his house, and a means to the end of establishing a legitimate lineage.

Miss Rosa returns to the theme of building in evil as she reflects on Sutpen's considerable but dubious achievement: "But then, so had vanity conceived that house and, built it in a strange place and with little else but his bare hands and further handicapped by the chance and probability of meddling interference arising out of the disapprobation of all communities of men toward any situation which they do not understand" (51). Sutpen's tragic flaw, by her account, is his incomprehensibility, his mystery, his keeping of some secret that, unacknowledged, festers into contagion. The house and the family are doomed insofar as they are perceived as extensions of his awful and sinister presence, and so, indeed, they become for the people of Jefferson appendages proliferating on the body of a monster.

In every respect Sutpen's house is a "house divided against itself," conceived and wrought in ambivalence and laid on a foundation of violence proportioned by guilt. The land was stolen from the Indians through brute power. The house was built on an economy of slave labor; the balance of power between master and slaves was a delicate one, the line between them thin. The legitimate heirs were shadowed by mulatto siblings of uncertain status with complex claims on the place and its proprietors.[6] It was a place where whites came in the front door and blacks in the back, yet where whites and blacks led an oddly parallel

existence, the lines of demarcation between them increasing in import in inverse relation to the gradual obliteration of conventional barriers: they conducted "the same parties; the identical music from identical instruments, crude fiddles and guitars, now in the big house with candles and silk dresses and champagne now in dirt-floored cabins with smoking pine knots and calico and water sweetened with molasses" (98). The women Sutpen allowed into his house threatened him like Delilahs, emasculating presences that he tolerated only by various strategies of resistance and defiance, allowing them no exercise of power that might threaten his own. Race, class, and gender were all lines of division that defined the conflicting forces operative in this house from the beginning. Sutpen's miscegenation blurred and weakened the lines of family structure and claims of inheritance.

Lines of color in this story are contiguous with lines of legitimacy; miscegenation therefore appears to undermine legitimate lines of inheritance. What is white diminishes and dies or becomes detached, removed from the land and the inheritance. What is black survives: primitive, without social or political status, but triumphant in survival and repossession. The house of Sutpen, bigamist, miscegenist, intruder, imperialist, whose energies are divided between his public and his hidden life, ends like the house of Usher, which finally opens along the crack that extends to its foundation, crumbles, and sinks to oblivion, returned to the earth as if in final punishment for satanic pride.

The multiple rifts within the house of Sutpen come to a head in the story of the two sons, Henry Sutpen and Charles Bon, who in their fashion reiterate the Old Testament stories of two sons divided by laws of inheritance or legitimacy: Cain and Abel, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau. Here, most importantly, the house of Sutpen breeds within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Henry is described as a "grim humorless yokel out of a granite heritage where even the houses, let alone clothing and conduct, are built in the image of a jealous and sadistic Jehovah" (109)—a product of a harsh southern Puritanism whose inherent contradictions create a moral universe that is a field of intolerable tension, driving those who live by its dictates to a state of radical uncertainty coupled with fanatical

compliance. Charles, Henry's urbane, worldly counterpart, is free of the puritanical obsession and guilt that weaken the legitimate line of Sutpen.[7]

The bond of intimacy that grows between Henry and Charles is proportionate to their fated opposition. They build a "rapport not like the conventional delusion of that between twins but rather such as might exist between two people who, regardless of sex or age or heritage of race or tongue, had been marooned at birth on a desert island: the island here Sutpen's Hundred; the solitude, the shadow of that father with whom not only the town but their mother's family as well had merely assumed armistice rather than accepting and assimilating" (99). Henry finally rides away with his half brother and "abjure[s] his home and birthright" (106) to go to New Orleans, Bon's world, where, Quentin's father reflects, "I can see him corrupting Henry gradually into the purlieus of elegance, with no foreword, no warning, the postulation of come after the fact, exposing Henry slowly to the surface aspect—the architecture a little curious, a little femininely flamboyant, and therefore to Henry opulent, sensuous, sinful" (110). And after that initiation and after Bon's revelation of his identity and his incestuous intentions toward Judith (his half-sister), one brother is compelled to destroy the other, as Miss Rosa dramatically recalls the denouement of the tragedy: "I saw Henry repudiate his home and birthright and then return and practically fling the bloody corpse of his sister's sweetheart at the hem of her wedding gown" (18). It is finally the "illegitimate" line that accedes to the inheritance, just as did the Gentiles, who, according to Christian theology, acceded to the inheritance promised to the chosen people, who had lost the vitality of faith and passion required to sustain it.

Both sons leave home and repudiate their father. Both return to meet their fate: Charles, to be killed; Henry, to wither into living death and eventually to perish at the hands of Clytemnestra, his mulatto half-sister. Reentering the house, each is doomed and ensnared in its secrets. When Bon returns home, Sutpen realizes that the moment of his return portends the destruction of the household. The potential of an incestu-

ous alliance with Judith, the necessity as it seems to him of keeping the secret of Bon's identity that would prevent that alliance, the high stakes of either keeping or revealing the secret, all come to him as he invites Bon into his house for the first time as an adult. Sutpen is aware of the fatal import of his act even as he opens the door:

He stood there at his own door just as he had imagined, planned, designed, and sure enough and after fifty years the forlorn nameless and homeless lost child came to knock at it and no monkey-dressed nigger anywhere under the sun to come to the door and order the child away; and Father said that even then, even though he knew that Bon and Judith had never laid eyes on one another, he must have felt and heard the design—house position, posterity and all—come down like it had been built out of smoke, making no sound, creating no rush of displaced air and not even leaving any debris. And he not calling it retribution, no sins of the father come home to roost; not even calling it bad luck, but just a mistake. . . . So he invited Bon into the house. (267–268)

The fatal moment that begins the long decline and fragmentation of his household comes by Sutpen's own invitation when he allows Charles, knowing the consequences, to return to the house a fully empowered and conscious man, a son become a rival and a threat, an alien whom Sutpen can neither deny nor acknowledge, the bastard offspring who has become the father's sign of contradiction. The history of the house of Sutpen, like any genealogical history, can be told only as a series of divisions. In a house built as a personal empire, such divisions can mean only vitiation of power. In the house's original integrity it was, Miss Rosa supposes, a double of its maker, whose ethos has survived the house's many changes of hands and character. It was, she recalls,

as though his presence alone compelled that house to accept and retain human life; as though houses actually possess a sentience, a personality and character acquired, not so much from the people who breathe or have breathed in them inherent in the wood and brick or begotten upon the wood and brick by the man or men who conceived and built them—in this house an incontrovertible

affirmation for emptiness, desertion; an insurmountable resistance to occupancy save when sanctioned and protected by the ruthless and the strong. (85)

Sutpen lived there at first in inviolate solitude—a kind of fierce virginity and original innocence from which every change represented descent. In that state, his house had a kind of integrity that was a direct and symbolic manifestation of the man himself, roughly magnificent, cold, unfeminized, monolithic. Therein the house was "true," if truth can be attributed to the incarnations of self that are bodied forth in man's creations. Indeed, Mr. Compson describes the Thoreauvian simplicity of Sutpen's first years in the great house as something oddly akin to virtue:

For the next three years he led what must have been to them [husbands and bachelors in town] a perfect existence. He lived out there, eight miles from any neighbor, in masculine solitude in what might be called the half-acre gunroom of a baronial splendor. He lived in the Spartan shell of the largest edifice in the county, not excepting the courthouse itself, whose threshold no woman had so much as seen, without any feminized softness of window-pane or door or mattress; where there was not only no woman to object if he should elect to have his dogs in to sleep on the pallet bed with him. (39–40)

And he lived out there for almost five years before he had speaking acquaintance with any white woman in the county, just as he had no furniture in his house and for the same reason: he had at the time nothing to exchange for them. (62)

Sutpen's marriage to Ellen Coldfield represents the first "violation" of this virginal integrity. The marriage is a concession to worldly norms, a compromise with the dictates of civilized life that here, as in so many American novels, is represented as an ambiguous attainment. Miss Rosa recalls the figure of Sutpen years after his marriage as having become portly:

The flesh came upon him suddenly, as though what the negroes . . . called the fine figure of a man had reached and held its peak after the foundations had given away and something between the shape of him that people knew and the uncompromising skeleton

of what he actually was had gone fluid and, earthbound, had been snubbed up and restrained, balloonlike, unstable and lifeless, by the envelope which it had betrayed. (80–81)

With marriage come the world and the flesh. The "uncompromising skeleton," like the blueprint of the grand design, is condemned to be fleshed out in imperfect and degenerating form—incorruptible idea made flesh and, like the house he built, subject to moth, dust, and corruption. The process of corruption begins in giving away something of his power to a wife, who, however unassuming, serves as a necessary evil who will provide him heirs and continuity even as she undermines the purity of his solitude. Ellen represents the beginning of loss—an old and common misogynistic notion deeply embedded in the fiercely patriarchal ethic Sutpen represents. Marriage already creates a house divided against itself, making of home a locus of the ancient sexual battles that, once entered into, leave no one unscarred.

When by this uneasy alliance Sutpen's house becomes Ellen's as well, his control over his domestic domain is compromised. This submissive woman breaks his hegemony and subverts his fanatical purposes. Yet for Ellen the house is a prison. Her predicament is classic: his dream, his house, the walls he erected around nothing, constitute the boundaries of her own existence. The house becomes the stage on which she must act out the drama of her own usurped destiny. His house is her fate, and she is in a real sense more wedded to the house than to the man. Miss Rosa, recalling bitterly Ellen's fatal consent to this captivity, is not completely baffled by this complicity. It has about it the ironic inevitability of the typical: "It may have been," Miss Rosa reflects, "for the sake of that big house and the position and state which the women realized long before the men did that he not only aimed at but was going to attain" (52).

Miss Rosa knows what it cost her sister to enter that house as Sutpen's bride. She calls it "that house for which she had exchanged pride and peace both" (15). Despite children and prosperity, Miss Rosa describes the house and Ellen's life in it as barren. "I saw her almost a recluse, watching those two doomed children growing up whom she was helpless to save. I saw the

price she had paid for that house and that pride" (18). Miss Rosa views her sister as having vanished into "an edifice like Bluebeard's" and there become "a mask looking back with passive and hopeless grief on the irrevocable world, held there not in durance but in a kind of jeering suspension by a man who had entered hers and her family's life before she was born with the abruptness of a tornado, done irrevocable and incalculable damage, and gone on" (60). The images of natural disaster Miss Rosa appropriates to describe Sutpen's actions and effects suggest again her ironic sense of the inevitability of the tragedy she retails. Bitter as she is, her business is not to blame Sutpen but simply to reveal him as a source of impersonal and tragic evil in whose given nature it is to destroy.

Ellen's children, and later her sickness and death, score the house with further lines of division. The fatal relation of her two children to Sutpen's illegitimate half-breed son and daughter place them, too, on the stage of an antique tragedy, doomed to be the innocent agents of division and destruction. Judith and Henry are passive where Clytie and Charles are active, their whole fate a function of circumstance rather than choice. Already in their generation the vitality of Negro blood gains a kind of moral ascendancy. In geometric progression the house of Sutpen is divided into two and then four conflicting interests and claims.

For awhile, as her mother lies sick and dying, the house is Judith's. She runs it with Clytie's, and eventually with Miss Rosa's, help, gradually transforming it into a nunnery of sorts.

And Judith. She lived alone now. Perhaps she had lived alone ever since that Christmas day last year and then year before last. . . . She lived in anything but solitude what with Ellen in bed in the shuttered room, requiring the unremitting attention of a child while she waited with that amazed and passive uncomprehension to die; and she (Judith) and Clytie making and keeping a kitchen garden of sorts to keep them alive; and Wash Jones, living in the abandoned and rotting fishing camp in the river bottom which Sutpen had built after the first woman—Ellen—entered his house and the last deer and bear hunter went out of it where he now permitted Wash and his daughter and infant granddaughter to live. (125)

Miss Rosa joins the household for a time on Ellen's death, entering into its barren life but not its secrets. She recalls being

kept from a particular room in the house by Judith, then mistress in her mother's stead.

"Don't you go up there, Rosa." That was how she [Judith] said it: that quiet, that still, and again it was as though it had not been she who spoke but the house itself that said the words—the house which he had built, which some suppuration of himself had created about him as the sweat of his body might have produced some (even if invisible) cocoon-like and complementary shell in which Ellen had had to live and die a stranger, in which Henry and Judith would have to be victims and prisoners, or die. (138–139)

Miss Rosa goes on to give an account of her time in Sutpen's house:

I stayed there and waited for Thomas Sutpen to come home. . . . I waited for him exactly as Judith and Clytie waited for him: because now he was all we had, all that gave us any reason for continuing to exist, to eat food and sleep and wake and rise again: knowing that he would need us, knowing as we did (who knew him) that he would begin at once to salvage what was left of Sutpen's Hundred and restore it. . . . I who had kept my father's house and he alive for almost four years, Judith who had done the same out here, and Clytie who could cut a cord of wood or run a furrow better . . . than Jones himself. (154)

The women live in inviolate celibacy as Sutpen did in his first days as proprietor of the house. In his absence it has become a peculiar nunnery, inhabited by three women each of whom has her own claim on his house and on him. Miss Rosa identifies Sutpen's house with Sutpen's person. They seem dependent but are actually utterly independent of the man whose spirit so holds them spellbound. "So we waited for him," she goes on.

"We led the busy eventless lives of three nuns in a barren and poverty-stricken convent: the walls we had were safe, impervious enough, even if it did not matter to the walls whether we ate or not. . . . We kept the house, what part of it we lived in, used; we kept the room which Thomas Sutpen would return to—not that one which he left, a husband, but the one to which he should return a sonless widower, barren of that posterity which he doubtless must have wanted who had gone to the trouble and expense of getting children and housing them among imported furniture beneath crystal chandeliers—just as we kept Henry's room, as Judith and Clytie kept it that is. (155)

Finally, she recalls the years of Sutpen's absence and his return:

Not absent from the place, the arbitrary square of earth which he had named Sutpen's hundred: not that at all. He was absent only from the room, and that because he had to be elsewhere, a part of him encompassing each ruined field and fallen fence and crumbling wall of cabin or cotton house or crib; himself diffused and in solution held by that electric furious immobile urgency and awareness of short time. . . . We were right about what he would intend to do: that he would not even pause for breath before undertaking to restore his house and plantation as near as possible to what it had been. (160)

The plantation has diminished to a tiny fragment of its original dimensions. On the day he proposed, he knew "definitely and at last exactly how much of his hundred square miles he would be able to save and keep and call his own on the day when he would have to die, that no matter what happened to him now, he would at least retain the shell of Sutpen's Hundred even though a better name for it would now be Sutpen's One" (168).

Eventually the house becomes Clytie's house, the illegitimate mulatto daughter, on all counts a dubious claimant to her father's inheritance. By legitimate laws of inheritance the house should have gone to Sutpen's son, but legitimate and illegitimate sons cancel one another out, and the house falls to the half-breed, illegitimate daughter—a situation that in every respect, by the laws of Sutpen's world, is a regrettable devolution. Like so many domestic slaves, Clytie is an intimate of the house from the time she is born, and she survives to destroy it. It is, in fact, more her house than Ellen's. The gradual passing of the house into feminine control parallels the gradual fading of the "white" power in the household into "black." The house is finally burned down by Sutpen's illegitimate half-black daughter in a suicidal act of insubordination, subversion, and triumph. It is the inevitable fate of such a house, the only resolution possible, fatalistically proving the proverb that a house divided against itself cannot stand.

Now, at the time of this telling, Judith, Clytie, Henry, Charles, Ellen, and Thomas Sutpen are dead. What remains of the house of Sutpen resides in the memory of Miss Rosa Cold-

field. Miss Rosa, as Faulkner might put it, "negatives" each of the other main characters. She is the sister who never became the wife, the maiden aunt who raised children she never bore, the perpetual guest in a house that is never her home. She is at various points a counterpart to Ellen, believing she will be Sutpen's wife but never becoming one in fact; a counterpart to Judith in filial duty, teaching and supporting her in the business of taking over the household on her mother's death, a contemporary, though belonging to Ellen's generation; a counterpart to Clytie in her similarly ambiguous position as intimate in a household to which she can exercise no legal or moral claim; and, most importantly, a counterpart to Sutpen himself. Miss Rosa is the only character in the story who is Sutpen's equal. Her lust for revenge is equal in its fanaticism to his lust for possession.

Characteristically, Faulkner doubles Sutpen's saga of displacement and degeneration in the story of Miss Rosa Coldfield's house. Miss Rosa's house, once her father's, and the house in which her father took his own life, is a counterpart to the house of Thomas Sutpen in a number of ways—a place as small and penurious as his is grand and flagrant in its magnificence, characterized by a Puritanism as small-minded and squalid as Sutpen's fanatical heterodoxy is unabashedly voracious. "So for the first sixteen years of her life she lived in that grim tight little house with the father whom she hated without knowing it—that queer silent man whose only companion and friend seems to have been his conscience and the only thing he cared about his reputation for probity among his fellow men" (60).

Like Sutpen's house, Coldfield's is a place of secrets to which Miss Rosa becomes privy by subversion and indirection:

Miss Rosa's childhood was passed, that aged and ancient and timeless absence of youth which consisted of a Cassandra-like listening beyond closed doors, of lurking in dim halls filled with that presbyterian effluvium of lugubriuous and vindictive anticipation, while she waited for the infancy and childhood with which nature had confounded and betrayed her to overtake the disapprobation regarding any and every thing which could penetrate the walls of that house through the agency of any man, particularly her father,

which the aunt seems to have invested her with at birth along with the swaddling clothes. (60–61)

Like Ellen, Miss Rosa "kept her father's house . . . until the night the aunt climbed out the window and vanished" (64), quietly waiting for the inarticulate battle between her and her father to terminate in the death of one or the other. Coldfield's house becomes a place, like Sutpen's house, of sickness and suicide in which survival is a matter of endurance of a kind that hardens the soul in bitterness. She inhabits it not as a home but as a tomb, sustained by memory and desire for revenge like the shades in hell, keeping watch over her father's last days as Clytie later does Henry's, harboring his secrets and her own and waiting for them to apotheosize in the moment of death.

[Coldfield] had closed his store permanently and was at home all day now. He and Miss Rosa lived in the back of the house, with the front door locked and the front shutters closed and fastened. He spent the day, the neighbors said, behind one of the slightly opened blinds with the big family Bible in which his and his sister's birth and his marriage and Ellen's birth and marriage and the birth of his two grandchildren and of Miss Rosa, and his wife's death . . . had been duly entered in his neat clerk's hand. . . . That night he mounted to the attic with his hammer and his handful of nails and nailed the door behind him and threw the hammer out the window. (82)

When Quentin finds Miss Rosa, the "little grim house" has regressed to a state of "impregnable solitude" (88). Miss Rosa's final revenge on the man whose rise and fall determined the trajectory of her own tragic existence is to have the last word. She comes into her inheritance after the death of Sutpen and the destruction of his house by assuming his story as her property. By right of inheritance, by right, we might say, of simple endurance, it has become hers. She, who views herself as the "rightful" wife of Thomas Sutpen, the barren woman whose line is stopped, takes her inheritance by subversion: she is in possession of Sutpen's story, and as storyteller, the whole "house of Sutpen" belongs to her. There is no one now with any vested interest to prevent the story from being told as she wishes to tell it.

She has nothing left to her but this story, and her right to it is something she establishes insistently. She is an eyewitness to the events she wants Quentin to set down; like the women of the Gospels passing an oral tradition to the four writers, she presses Quentin into service as witness to her testimony. "I lived for two years under the same roof with him" (19), she reminds Quentin. And yet she has been excluded from the deepest secrets of the Sutpen household, the secrets borne by blood, and so her claim to privilege is ambiguous. This is her bitterness—to have been condemned to the role of excluded intimate. As a child, she recalls, "though Ellen was my own sister and Henry and Judith my own nephew and niece, I was not even to go out there save when papa or my aunt was with me and. . . . I was not to play with Henry and Judith at all except in the house" (21).

Rosa believes, however, that precisely as a function of her marginal position in relation to this family, she has a privileged perspective on the events she relates. She claims for herself an oracular status, recalling how aware she was of things the members of Sutpen's own household seemed oblivious to:

Even when I saw it for the first time that I could remember I seemed already to know how it was going to look just as I seemed to know how Ellen and Judith and Henry would look before I saw them for the time which I always remember as being the first. . . . I only knew, as soon as papa and I crossed the threshold, that he was not there: as though with some almost omniscient conviction, knowing that he did not need to stay and observe his triumph. (26)

In another memory she is a child, "standing motionless beside that door as though trying to make myself blend with the dark wood and become invisible, like a chameleon, listening to the living spirit, presence of that house, since some of Ellen's life and breath had now gone into it as well as his, breathing away in a long neutral sound of victory and despair, of triumph and terror, too" (27).

For Miss Rosa reality has diminished as memory has enlarged. Everything about Miss Rosa represents diminishment. When Quentin answers Miss Rosa's summons, he observes that her house seems "smaller than its actual size . . . with an air, a quality of grim endurance as though like her it had

been created to fit into and complement a world in all ways a little smaller than the one in which it found itself" (10). Miss Rosa's person answers the same description as he finds her sitting in the dark, suffocating, tomblike hallway, full of "slow heat-laden time," very still—a "small figure in black which did not even rustle, the wan triangle of lace at wrists and throat" (10–11).

In this house of the dead, as if in concession to its pull toward death, Miss Rosa gives away her inheritance to Quentin, like Esau's "mess of pottage," as a commodity to be sold, to be converted by the alchemy of the marketplace into furniture for his wife's house, should he have one: "So maybe you will enter the literary profession as so many Southern gentlemen and gentlewomen too are doing now and maybe some day you will remember this and write about it. You will be married then I expect and perhaps your wife will want a new gown or a new chair for the house and you can write this and submit it to the magazines" (9–10).

This is her final revenge: to give away Sutpen's story, in so many ways representing the "secrets of the South" and its shame, to be put before an anonymous public in a degraded form, a commodity to sell in the marketplace. She shows Quentin a way to build his house on the ruins of Sutpen's. But with the story she gives him a charge: to find out the mystery of the house. "There's something in that house," she tells him. "Something living in it. Hidden in it. It has been out there for four years, living hidden in that house" (172). To take possession of his inheritance, Quentin must find out what that something is.

Quentin himself is neither detached nor objective about the story he hears. It comes to him, as it has to Miss Rosa, as a destiny. It was Quentin's great-grandfather, General Compson, who had been Thomas Sutpen's friend and foil, his confidant and supporter in the early days when he came like a wild man out of the wilderness bewildering the town and leaving behind him a trail of suspicion and apprehension. The general was the Starbuck to Sutpen's Ahab, friend and mate to a man of whose purposes he remained somehow innocent. "It was General Compson," Quentin learns, "who offered to lend Sutpen the money to finish and furnish his house, and was refused" (41).

Quentin, more than any other candidate for this epic task of reconstruction, is in a position to revise and qualify Miss Rosa's weighted tale. Seeming more definitive in its rational account of the man and his endeavor, the sympathetic portrait of Sutpen transmitted through Quentin's judicious father, a lawyer, whose father knew Sutpen, and who has seen the documents and read the accounts written in local record, throws Miss Rosa's intensely dramatic, highly charged version of the story into the realm of fiction and myth-making. It is left to Quentin to measure the epistemological validity and the worth of the variant versions of the story. As Quentin absorbs Sutpen's story, filtering it through his own prismatic consciousness, it takes on new mythic significance; what has been for Miss Rosa defining family lore becomes on the larger canvas of Quentin's cosmic imagination a southern epic with cultural implications that extend far beyond his own fatalistic sense of predestined inculpation. What she describes he understands prescriptively; he recognizes the pattern of Sutpen's rise and fall, his building and destroying, as a prophetic formula.

Quentin is called, like one of the reluctant prophets, to receive and bear a message to and about his people that his own people will not heed and that outsiders will not comprehend. Sutpen's story is given to him for several reasons: because as a descendant of Sutpen's friend and confidant, General Compson, Quentin has a right to the story; because Quentin is a literary man, someone who can tell the story and shape it and who knows enough to tell it faithfully but also enough to recognize the consequences of truth-telling; because he will translate the story into new terms for a new generation; because he is mobile. He will take the story and escape with it. Borne into the North, published in magazines, as Miss Rosa hopes, the story of Sutpen will grow to the dimensions of myth, and Sutpen will be flung on the world like the image of Jesus, to be distorted and battered and betrayed in a thousand ways by just such readers as the good-hearted Shreve, who are fascinated but do not understand.

Quentin is neither builder nor destroyer but is a demoralized "savior" whose psyche and body provide a vacant space in which all of history and myth are reiterated, shrunken to the confines

of a single tortured mind condemned to "forge," like Stephen Dedalus, "the conscience of his race." Quentin is a "second Adam," whose inheritance is legend, story, myth. His childhood was full of names and stories, which were his inheritance: "His very body was an empty hall echoing with sonorous defeated names; he was not a being, an entity, he was a commonwealth. He was a barracks filled with stubborn back-looking ghosts still recovering, even forty-three years afterward, from the fever which had cured the disease" (12).

Quentin's historical position as inheritor prevents him from becoming a builder. Rather than a plantation in the wilderness, he constructs a house of fiction made of the remnants gathered from his father and grandfather and Miss Rosa. His is the burden of reconstruction, the desolate task of rebuilding out of the heap of broken images that lay scattered abroad in the South after the Civil War. Like a reluctant prophet, he does not want the task, and yet it seems there is no one else. So he takes the burden of the story and begins the patchwork process of fitting pieces together, listening, gathering material, shaping it, honing it, giving it new words, substituting his words for Miss Rosa's or hers for his, matching her words to his father's and grandfather's, comparing accounts, claiming none of them, his only authority consisting of the profound and oppressive sense of his destiny lying in the task. The first step in assuming this burden is to witness the final destruction of Sutpen's house. With Miss Rosa Quentin makes his fatal pilgrimage for this purpose:

The drive seemed interminable. He knew the place. He had walked from the gate to the house as a child, a boy, when distances seem really long (so that to the man grown the long crowded mile of his boyhood becomes less than the throw of a stone) yet now it seemed to him that the house would never come in sight: so that presently he found himself repeating her words: "If we can just get to the house, get inside the house," telling himself, recovering himself in that same breath: "I am not afraid. I just don't want to be here. I just don't want to know about whatever it is she keeps hidden in it." But they reached it at last. It loomed, bulked, square and enormous, with jagged half-toppled chimneys, its roofline sagging a little; for an instant as they moved, hurried toward it Quentin saw completely through it a ragged segment of sky with three hot stars

in it as if the house were of one dimension, painted on a canvas curtain in which there was a tear; now, almost beneath it, the dead furnace-breath of air in which they moved seemed to reek in slow and protracted violence with a smell of desolation and decay as if the wood of which it was built were flesh. (366)

Quentin enters the house, finds it dark, slips along a dark passage to open the door for Miss Rosa. Clytie, who is already there, strikes a match. She has "a bunch of enormous old-fashioned iron keys, as if she had known all the time that this hour must come and that it could not be resisted" (368–369). When the fire starts he watches with ironic detachment: "It would be a good three minutes before it could reach the house, the monstrous tinder-dry rotten shell seeping smoke through the warped cracks in the weather-boarding as if it were made of gauze wire and filled with roaring and beyond which somewhere something lurked which bellowed, something human since the bellowing was in human speech, even though the reason for it would not have seemed to be" (375). Even as the house is utterly demolished, its mystery speaks from the ruins and remains to haunt the witnesses.

In a dorm room at Harvard, far from home and South, and because there is no one else to tell, Quentin transmits this legend, betraying the secrets of the tribe, to a "Gentile"—a stranger, a northerner, a Canadian, his roommate, Shreve. The extent of Quentin's personal investment in the story becomes, to his horror, more and more evident as he attempts to reconstruct it for Shreve. In the face of a truly disinterested, albeit fascinated, audience, Quentin's own psychic investment in Sutpen's story as personal and cultural myth and his inability to explain the way it has shaped his consciousness or to rid himself of his compulsive sense of involvement in it drive him finally to desperate silence, defeat before the inexplicable, which closes over him and his tribal secrets like water, drowning the words with which he flails to keep afloat.

Shreve cannot possibly grasp the story's meaning and in receiving and retelling it distorts and falsifies it. As Quentin lapses into silence, Shreve takes over the task of narration, pursuing

with the excitement of an archaeologist the fragments that will provide clues to the mysteries of this history. His reconstructions are bound to be false. In the hands of this stranger the house of Sutpen will be entirely remodeled. Shreve invests the story with his own uninvested enthusiasm and with an ironic note of comedy. He characterizes Aunt Rosa as "this old dame that grew up in a household like an overpopulated mausoleum" (176) and Sutpen as "this Faustus who appeared suddenly one Sunday with two pistols and twenty subsidiary demons and skuldugged a hundred miles of land out of a poor ignorant Indian and built the biggest house on it you ever saw and went away with six wagons and came back with the crystal tapestries and the Wedgwood chairs to furnish it and nobody knew if he had robbed another steamboat or had just dug up a little more of the old loot" (178).

In telling the story to Shreve, Quentin completes the turn of a large tragic cycle; just as Sutpen brought foreign influence onto American soil, brought his West Indian natives and his French architect, and forged a life and a home out of borrowed and stolen elements, so Quentin is paying the penance for that heritage of invasion, miscegenation, and betrayal by betraying in his turn. He is giving away the story of the South to an outsider, a northerner, who will neither appreciate nor comprehend it with anything but a detached, or even prurient, fascination with what seem to him peculiarities, aberrations, inexplicable allegiances, and passionate enmities clung to from a past that keeps invading and taking over the present. Once again Quentin reviews for Shreve the story whose telling has assumed such shifting shapes, built and rebuilt and condemned to be rebuilt again. Like Thoreau, Quentin has appropriated the ramshackle remains of another man's building to shave and fit and fashion into something habitable for himself. But his experiment does not work. Shreve takes over the story as Quentin lapses into inarticulate silence. He cannot tell the story here, in this place, to this uncomprehending listener. And so he is left with silence, his house of fiction collapsed about his ears, and we, like Shreve, are left to overtake the reconstruction.

Like Quentin, the author has, as it were, given away his inheritance to an anonymous audience. The secrets of the South

are written and sold, plowed back into the economy, sold in the marketplace, perhaps to buy a chair for the house. The word become flesh becomes words again in an old tragic cycle of building and destruction. To tell is to create and simultaneously to destroy. We assume our place after Shreve in the lineage of illegitimate inheritors. Throughout the novel we are being invited to participate in the business of reconstruction. We are given the materials of a story, as Quentin is, filtered through multiple minds, shaped by the pressures of several distinct relationships in which some events are suppressed and others exaggerated. And out of these "broken images" we seek to fashion a whole that will incorporate all the pieces left as detritus from the past.

For us, as for these explorers of the past, two accounts surface that, juxtaposed, reveal the magnitude of what has been achieved and destroyed. One is a written recollection by General Compson: "You have seen the rotting shell of the house with its sagging portico and scaling walls, its sagging blinds and plank-shuttered windows, set in the middle of the domain which had reverted to the state and had been bought and sold and bought and sold again and again and again" (213). The other record is Sutpen's own account of his magnificent defeat—as explained to General Compson—which is full of a poignancy and an immediacy that serve as a ground and measure for the tales Sutpen's story has spawned: "You see, I had a design in my mind. Whether it was a good or a bad design is beside the point; the question is, where did I make the mistake in it, what did I do or misdo in it, whom or what injure by it to the extent which this would indicate. I had a design. To accomplish it I should require money, a house, a plantation, slaves, a family—incidentally of course, a wife. I set out to acquire these, asking no favor of any man" (263).

The story, like the house, is a structure erected around a vacancy—a betrayal of history, a confession, and a defense. It is a place to enter into with curiosity and distrust because ghosts lurk there. It is a structure of deferred meaning, virtual meaning, almostness. The structure is never closed; the house is never quite finished. In it there are chambers within

chambers—stories within stories. Faulkner's narrative is a place we enter; like Miss Rosa's "office," it is an enclosed place, dim, hot, airless, where things circulate but do not escape. Like Quentin's mind, it is a repository for layers on layers of history, and history has become story, has become legend, has become myth, has become destiny, has become mirror for the individual psyche that seeks to comprehend the whole and so encompass it or inhabit it. We are involved in spite of ourselves in the business of building and habitation.

How do we become comfortable in such an imaginative space—with many mansions superimposed on one another? We start by learning to live in suspension, to wait and listen as Miss Rosa does at many half-closed doors, to gather the mysteries that remain unexplained. The inscape of the sentence teaches us how to do this waiting and listening. Faulkner's sentences are edifices that, like the whole narrative, have many chambers and doors that open into unexpected places. In a single sentence we can shift planes or frames of reference several times. A sentence is a structure within which we must maneuver through passageways to find the exit. We infer at the beginning what the end will be but must keep correcting our assumptions as we move through it, hitting walls as in a maze, and having to retreat and seek another passageway. If in the end the resolution is not found, we are propelled on to the next sentence to begin the puzzle again. The following sentence, for instance, about the French architect, leads us through a maze, slowing us at every turn, teaching us to be alert to the relations expressed, ambiguous, complex, and multiplying in their complexity as the wave crests:

Not, General Compson said, the hardship to sense and the outrage to sensibility of the two years' sojourn, but Sutpen: that only an artist could have borne Sutpen's ruthlessness and hurry and still manage to curb the dream of grim and castlelike magnificence at which Sutpen obviously aimed, since the place as Sutpen planned it would have been almost as large as Jefferson itself at the time; that the little grim harried foreigner had singlehanded given battle to and vanquished Sutpen's fierce and overweening vanity or desire for magnificence or for vindication or whatever it was (even General

Compson did not know yet) and so created of Sutpen's very defeat the victory which, in conquering, Sutpen himself would have failed to gain. (38–39)

This passage pulls several grammatical tricks: it confuses antecedents, thereby forcing the reader to review earlier information to see how things are joined; it uses parallel constructions that seem to promise closure but fail to close and veer instead into a new clause by means of a colon or semicolon; it deconstructs its main claim—that the architect has achieved some kind of victory—by refusing to name what has been vanquished, substituting instead several possibilities, leaving it at "whatever it was," emphasizing the dissolution of the object with the parenthetical "(even General Compson did not know yet)," reminding us that our main source of information is unreliable; and, finally, it ends by leading us into a syntactical maze that demands a doubling back and reassessment of the possibilities of logical meaning. Each element opens a door on an array of possibilities; going through one door, we find ourselves led back to the place we thought we had left. We are kept in a realm of uncertainty, as in a hall of mirrors with the repeated "or," leaving possibilities open, the whole thing setting history in the conditional tense. What is called for is insight, vision, even inspiration. We cannot be passive listeners—in listening we, too, become interpreters and authors, assuming responsibility for what we hear. We are therefore challenged to be those who "have ears to hear," to see past the dazzling surface to the grand design, to be, ourselves, readers of blueprints and architects willing to restore, reconstruct, and renovate the crumbling structures of the past.

If Absalom, Absalom! is a moral tale, it is of the kind told in the parable of the man who built his house on sand. In that spirit its epigraph might be drawn, appropriately enough, from the Old Testament, itself so full of stories of building and destruction: "Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it" (Psalm 127:1).