Charles B. Griffith: Not of this Earth

Interview by Dennis Fischer

* Some of his early scripts were unique

and unusual, even brilliant.

—Mark Thomas McGee , Fast and Furious:

The Story of American International Pictures

Of all the writers who worked for Roger Corman, the most unjustly neglected is Charles B. Griffith. When films such as Not of This Earth or The Little Shop of Horrors are discussed, his contributions are often ignored; but it is Griffith's screenplays that have made a number of these fondly remembered, offbeat films as enjoyable as they are.

In getting these films made, Griffith has had a number of bitter experiences, not the least of which was having his story and characters from The Little Shop of Horrors made into a musical without his consent.

Howard Asherman, who wrote and produced the musical remake, dealt only with Roger Corman, who claimed to own all the rights. Since then, there has been a settlement that will give Griffith credit on future productions of the play and the film. Today, after years of fashioning scripts for films with low budgets and encountering endless hassles, Griffith has trouble finding work. He has been classified as a writer and director of nonsense. "They think of me as a crazed, far-out writer," said Griffith, "so I'm not taken seriously."

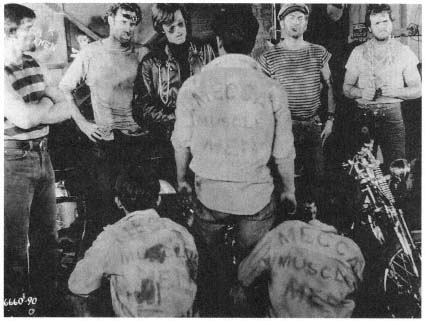

This is highly unfortunate. It is not Corman's direction that draws people to The Little Shop of Horrors; it is the blackly humorous plot and outrageous comedy. Griffith's film Gunslinger was the first western to have a female marshal. Not of This Earth is an intelligent science fiction revamping of Dracula. Rock All Night helped introduce the fabulous Platters. The Wild Angels led to a series of biker movies and helped launch the careers of Peter Fonda and Bruce

Dern. Eat My Dust, both written and directed by Griffith, was a top-grossing low budgeter. Mostly, Griffith will be remembered for the wild comedy of Little Shop, Bucket of Blood, and Death Race 2000, which made B movie viewing an unexpected delight.

While Griffith's films are well documented, little is known about the man himself . . .

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Plays include the story and script basis for the musical stage version of The Little Shop of Horrors.

No one ever asks me about my background . . . my roots were in show business, since my mother was an actor; my father, when a young man, was in vaudeville; and my grandfather was a tightrope walker in the circus. It was automatic that I would go into the business. I went to military school but nothing else really interesting ever happened to me. I got into the picture business as a result of some scripts I did for the 1951 soap opera Myrt and Marge. My grandmother played Myrt, and my mother played Marge.

How did you begin your association with Roger Corman?

I was out here with my grandmother, writing TV scripts, which were never made, and trying to break in as a screenwriter. I had written about seven

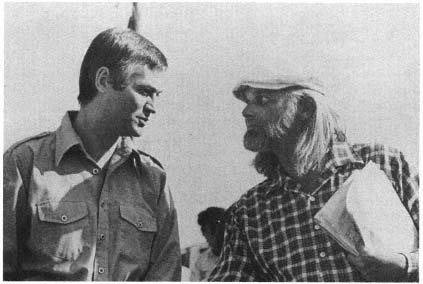

Roger Corman and writer-director Charles Griffith (right) on the set of Eat My Dust!

screenplays and a friend of mine, [the actor] Jonathan Haze, took them all over to Roger. Haze was already working with [the actor] Dick Miller and [the writer] Bobby Campbell and a lot of other people[*]—they were all crazy schlubs in the early fifties. Anyway, Roger called me and hired me to write a western, which I did, and which was never made. Then I wrote another western, and it wasn't made either. Then Corman taught me about budget. My third try was Gunslinger, and that one was made in 1955.[**]

It was supposed to be a six-day picture, but it got rained out, so it took seven. It was shot in the rain around an old ghost town, and it came out gorgeous. No one had shot in that light. They always thought you had to have hard light and hard reflectors and everything. You had that English countryside look right out in Topanga Canyon.

Your first science fiction script was It Conquered the World, but it was credited to Lou Rusoff.

Lou Rusoff had a brother dying in Canada, and he needed the money. The script Lou wrote was very confusing, so Roger gave it to me. I had three days to rewrite it, so I started from scratch.

Didn't you also play a scientist in that film?

That's right. I was also the sailor that died at the beginning of Attack of the Crab Monsters. Beach Dickerson was steering the boat, and when he swerved, I fell out. The boat went over me, and I was hit by the propeller. The sound man ran to rescue me, which got Roger mad because he ran into the shot.

Despite their low budgets, many of the science fiction films you wrote in the fifties had some interesting ideas. For example, Not of This Earth used teleportation long before The Fly. How did that film come about?

After I wrote Gunslinger and had patched up It Conquered the World, I went over to Roger's office, which was the size of a dinette, and said, "Don't you think it's time to do another science fiction film?" He said, "Okay, go ahead," and that was that. So I wrote Not of This Earth, and that started all this X-ray eye business. Most of Roger's themes got established right in the beginning. Whatever worked, he'd come and take again, and a lot of things got used over and over . . .

During the production of Not of This Earth, I was married to a nurse, and she helped me do a lot of medical research. I remember how we cured cancer in that script. Somehow the film was a mess when it was finished. About the time we saw Gunslinger, my wife was so shocked at the difference between the script and the picture that she never went to see another movie of mine.

How did Attack of the Crab Monsters come about?

* Robert Wright Campbell was nominated for an Oscar for his co-script for Man of a Thousand Faces. An early Roger Corman stalwart, he wrote or cowrote Teenage Cave Man, The Young Racers, Masque of the Red Death, and Hell's Angels on Wheels, as well as other low-budget classics.

** Charles Griffith's writing partner on Gunslinger, Not of This Earth, Flesh and the Spur, Naked Paradise, and The Undead was Mark Hanna—who is not mentioned in this interview.

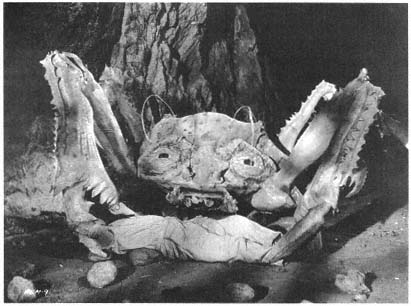

"Made of Styrofoam and fiberglass": a scene from Attack of the Crab Monsters.

Roger came to me and said, "I want to make a picture called 'Attack of the Giant Crabs,' " and I asked, "Does it have to be atomic radiation?" He responded, "Yes." He said it was an experiment. "I want suspense or action in every scene. No kind of scene without suspense or action." His trick was saying it was an experiment, which it wasn't. He just didn't want to bother cutting out the other scenes, which he would do.

We didn't cut much in those days because pictures always came in short. So that's what happened. There was always something going on in that picture, but it was dumb. I mean, in the script, [the actor] Mel Welles says, "Strange, there's no sign of life on the island," and Roger cuts to seagulls taking off from the cliff. Caw, caw. (Chuckles. )

Why did he do that?

Oh, atmosphere. He wasn't really listening to the dialogue.

You didn't like the idea of radiation making things big?

It was called "gobbledygook" and was meant to sound rational. Did you know that Ed Nelson was under the crab prop? He later ended up starring in Peyton Place. Jack Nicholson may have been under it part of the time. Yeah, he was around the set, schlepping in those days, too.

The crab was made of Styrofoam and fiberglass around an aluminum frame, was fifteen feet long, cost four hundred dollars, and it wouldn't sink. I

had to shoot it underwater, but there was no way to get it under water. [Griffith was second unit director.] We tried tying iron and rocks and things on it, but that didn't work. It flew up out of the water whenever we tried to get it to sink. But, despite our problems, Not of This Earth and Attack of the Crab Monsters were released on a double bill that made a 400 percent profit the first week.

The monster from It Conquered the World was not much of a monster either. When [the female lead] Beverly Garland first saw it, she said, "This SOB couldn't conquer anything," gave it a good kick, and knocked it over. In Not or This Earth, [the actor] Paul Birch was supposed to wear wraparound glasses, so you couldn't see the sides of his eyes. They stuck gaffer's tape on the sides of his glasses. You can see it if you look. In that film, I was in the scene at the newsstand at Las Palmas.

I had the worst time with titles. I hated some of those titles they put on the films. I did one called Teenage Doll, where every page of the script was rejected by the censors, and I had to write it over again during the weekend. I once wrote a script in twenty-four hours called Rock All Night. Lord Buckley was supposed to play Sir Bop in that film. He was a friend of mine, and I used to write material for him. He was a great character.

After that came The Undead.

One day Roger said, "I want you to do a Bridey Murphy picture." Bridey Murphy [i.e., The Search for Bridey Murphy, 1956] was being done at that time as a big-budget picture, and the book was still relatively popular. [The book and the film were about a woman who, when hypnotized, remembered her past lives.] I thought it would be dead by the time we could get anything out, but I wrote this story which I initially called "The Trance of Diana Love." Curiously, I separated all the different things with sequences with the devil, which were really elaborate, and the dialogue in the past was all in iambic pentameter. Roger got very excited by that. He handed the script around for everybody to read, but nobody understood the dialogue, so he told me to translate it into English. The script was ruined, but The Undead [the final title] was a fun picture to shoot, because it was done in ten days at the Sunset Stage, which was a supermarket on Sunset Boulevard. We filled it with palm trees and fog, and it was the first time Roger had used any of that stuff. He didn't like to rent anything. You could see the zipper on the witch's dress and all the gimmicks were very obvious and phony—Roger deliberately played to skid row, a degenerate audience.

I was surprised to discover that you directed your first film in 1957.

I started out as a director on Forbidden Island. I was trying to raise money to make independent low-budget pictures and wound up at Columbia with a five-picture writer-producer-director contract. I made two pictures under it, wrote and produced both of them, and directed one. [The other film Griffith produced was Ghost of the China Sea, with David Brian and Jonathan Haze, which was directed by Fred F. Sears.] They were really terrible. It stopped me for twenty years from ever directing again. They were really rank. You see, I

got chicken and started to write very safely within a formula to please the major studios, and of course, you can't do that.

How did the idea of combining a monster movie and a gangster melodrama come about? That's a rather bizarre combination.

You see, we had set movies that we would do. One of them was Naked Paradise, which was made in 1956 about a robbery in a pineapple plantation in Hawaii where the hero is operating a small sailboat and is hired by the crooks to take them to safety. When there's a robbery in Hawaii, the government shuts down the seaports and airports, and nobody can get out. So that was the thing. The crooks hung around in this house waiting to be picked up while all the action happened, and they all kill each other off.

That was successful, so we did it again in South Dakota. Roger says, "I want Naked Paradise using a gold mine instead of a pineapple plantation. Put it in South Dakota and add a monster." I didn't know how to add a monster to that script, so I had it all wrapped up in a cocoon in a cave just threatening to break loose all the time. That became Beast from the Haunted Cave.

Creature from the Haunted Sea was the same picture again, only this time instead of a plantation, it's the Cuban National Treasury, and the same gang of crooks taking off, but with an added zaniness, because Roger wanted another comedy. He still didn't know that the comedies were going to flop. The monster was made by Beach Dickerson for fifty dollars with a fur coat, two PingPong balls, and garden trowels for claws.

Creature from the Haunted Sea was the simplest of the comedies. Roger called me about three o'clock one morning. At the time, he was shooting The Last Woman on Earth [1961], which Robert Towne wrote, down in Puerto Rico. He got me to write the script for Haunted Sea in three days, and I sent it down to him in pieces. I didn't get to read the first scenes to see what the hell had gone on in them. It was definitely off the wall. He'd shot about half of it, maybe two-thirds, and then Roger decided he wanted to play a character. So I wrote the character of Happy Jack Monahan for him to play—who commits suicide, falls in love with a whore, cries, and who has to do every possible emotion. Roger had to hire an actor to do it. He was enraged! (Chuckles. )

The pictures didn't make any money because he was releasing them through his own Filmgroup Company, and he knew right away that comedy was not automatically an exploitation market. But he tried it again with The Raven [1963].

How much time did you have to write the screenplays for Bucket of Blood and Little Shop of Horrors?

Five days each. We did Bucket of Blood first, which was not meant to be a comedy, according to Roger. It became one because of me. It was the same situation where these sets were going to stand for another week.

The ones from Diary of a High School Bride?

Right, you know the story. Bucket of Blood had to be rushed through, and it had to be a comedy. Roger asked me, "How do you shoot comedy?" and I told

him to shoot it just like anything else. That was that, and it worked. We got applause on the set during the reading of the beatnik poetry, and that got Roger very excited. It was the first time anybody had ever liked anything. So we had to do it again right away. We sat down during shooting, and he insisted that it had to be the exact same picture, scene for scene, with just some of the names changed and so on. And I figured, "Oh, well, I'll just go from satire to farce, and he'll never know the difference."

Bucket of Blood is one of the few films that chronicles something of the beatnik era.

The beatniks in the coffeehouse scenes were all my friends. I didn't know too many of the poets, but everybody went to coffeehouses in those days. And the thing is, those were the sets that were there to shoot, the ones from High School Bride. Roger said, "Write a horror picture for those sets." There was a beatnik coffeehouse, a jail, a funky pad with nothing in it, and the lumberyard was the studio lumber department. So there really wasn't much of a choice. That's what dictated it being a comedy.

And Little Shop of Horrors was actually shot in two days and three nights?

Roger shot the interiors in two days on the stage—fifty pages a day—and I did the exteriors all around town, which took four days and nights. Mel

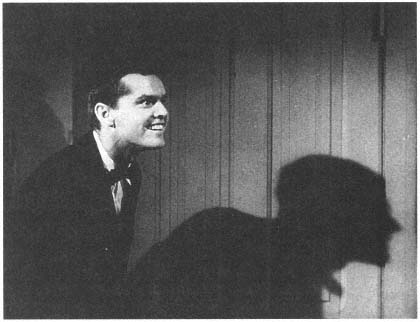

Jack Nicholson's dental appointment, a famous scene from The Little Shop of Horrors.

Welles, who produced second unit on Little Shop, helped out, but that was about the entire crew. Everybody else we got from skid row. We gave them ten cents a shot to act in the picture and got all kinds of good stuff. We got fifteen minutes of picture for $1,100, which was not too bad. The whole picture cost $27,000.

Didn't you also play a holdup man in the film?

Actually, I played four parts—the guy who runs out of the office with his ear bitten; the gangster that sticks up the flower shop and gets eaten by the plant; a shadow on the wall; and the voice of the plant, which was supposed to have been dubbed, but I did it on the stage, so Jonathan Haze would have something to react to. We just left it in because to dub over would have been a little too much money and trouble.

All my relatives were in that picture too. My father was the guy in the dentist's chair who got the mirror broken in his mouth. My kid brothers and sisters were in the crowd scenes. At that point, Roger and I were getting along very well, and I got away with a lot. I got away with rehearsing the cast ahead of time. Roger wouldn't let you do that later. It would take too much time.

Now you can't change anything unless he orders it changed. You can't try anything. The director of Deathsport [Henry Suso] came up to me and said he had a fabulous idea of shooting at night. I said, "You'd better tell that to Roger." He had worked out how he could use filters to get "day-for-night." Roger told him no night and no day-for-night. That was it. Anything you'd suggest to him, he'd say no. Anything. Ask anybody who works for him now. He'll gather people together and tell them nobody in his company knows how to make a picture.

The talents that worked for Roger got their chance because they were willing to work for nothing. These days everything is stolen. The ideas are stolen, the money is stolen from the people doing the work, the medical benefits are stolen, the residuals are stolen—there's no pension or welfare—and then the final picture is stolen from the audience because it's a piece of crap. That's low-budget exploitation picture-making.

Getting back to Little Shop of Horrors . . . I didn't even know it had been released. I had moved to Israel and then to Rome after making Atlas. When I was in Rome, Michael Reeves phoned from Montreal, but he said he had to get off the phone because Little Shop of Horrors was on television and everybody in town was watching it. That was the first news I'd heard that Little Shop was going to be a cult picture.

I'm curious about Atlas. I don't think I've ever seen it.

You're lucky. I've got a print of Atlas, and it's probably blood red by now. Atlas was a mess. It was a doomed project. I was involved in an Israeli war picture about helicopters, which never got finished, when Roger decided to make Atlas. This was after Little Shop, and I wanted to make it as Atlas, the Guided Muscle, but Roger wanted to make a Hercules, Italian-type thing.

Roger had a deal to shoot it in Puerto Rico, so it was going to be a jungle picture about Atlas and Zeus. Ancient Greece could have jungles, so why not?

But I was on my way to Israel because of the helicopter picture that collapsed in the desert. So Roger and I flew to New York together, and we worked on the details of Atlas. Then I boarded a ship going to Israel. I made it to Naples and received a cable saying the company had gone bankrupt and good luck. I was stranded in Israel for two years, and Roger wouldn't send me the fare to get out. I wound up doing some pictures in Israel [Hatsankanim and Frontier Ahead ].

Then Roger called me up from Athens and said he was going to do Atlas there instead of Puerto Rico after all, but I had to rewrite the script completely. So I went to Athens, and he paid me $200 to rewrite it and $50 a week to be associate producer, production manager, action director, do first-aid duty and everything else. He picked up a girl [Barbara Comeau] who did all the other work. She was wardrobe, script girl, and makeup, and she had no experience at all. "Women know how to do makeup," Roger says, "and anybody can do scriptwriting."

We used local talent from around the town near Athens, and the picture was written in just a few days. It was terrible. Frank Wolff and a couple of other actors came over, but they were very rebellious. Roger was in a towering rage throughout. There was a Greek cameraman and a Greek crew. Nobody knew left from right. The army couldn't march. They tore the noseguards off their papier-mache helmets, so that their relatives could recognize them in the picture, and there was paper hanging down from their helmets. The tips of their spears were hanging down because they were made out of rubber, which I had to have done at a tire shop around the corner of the set. It was a lot of fun.

We were shooting in public buildings, and of course, they threw us out of all of them. The permits said we could shoot there, but not with actors. So I'd go to all the archaeological sites and use the excuse that there were a lot of wars around here lately [in the script]. We bribed the guards at the gate to let us shoot. Roger broke his sunglasses in half and had a temper tantrum. He went a little mad during that picture. We went off afterwards and got shipwrecked.

One night we were in Athens just before Atlas started, and we went out and met some pimps in blue shirts who were passing out leaflets for free beer in one of those whorehouse nightclubs. I tried to tell Roger what it meant. He said, "Free beer. It says right here 'One free beer,' so let's get a free beer." We got a free beer and were immediately hustled by these chicks with a glaring bouncer behind them. We went out and had another free beer until we came to this place that said it had a floor show at ten o'clock and 2 A.M.

Roger said, "Let's go back and see the floor show at 2 A.M." We returned, and there were these two hookers who came and sat with us. "Aren't you going to buy us a drink, honey?" So Roger started buying them champagne, and he had this girl sitting on his lap, necking with her, and I just sat and

watched the whole thing. There was still no floor show, however, and Roger got mad. The bill finally came, and it was for sixty dollars. "I'm not paying sixty dollars for this," Roger said. "And there's no floor show!" The band started walking across [the floor], and we ran out. We escaped from the place and we didn't pay the bill.

But the Greeks froze the money we brought in, so we couldn't use the cash to shoot the picture. We all had to share hotel rooms, but nobody did any sleeping. They got me cheap at fifty dollars a week.

Weren't you supposed to write The Gold Bug for Corman's Poe series?

Yes, I was supposed to write The Gold Bug for Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, and Basil Rathbone. I thought, "Oh, boy, what a cast!" I got very excited. When they were doing Masque of the Red Death in London, I met Vincent on the set; and Roger told him what I was doing, and he said, "Yes, yes, tell me about it." I said, "Well, you're taking Basil Rathbone down a burned-out corridor of your southern mansion with no roof on it and the walls are charred and you're using it for a hock shop for all the family heirlooms and you're showing him all the family portraits in the hall . . . "

Bruce Dern (second from left) and Peter Fonda (in leather jacket) in The Wild Angels.

"Oh no," Price said, "Not again! I can't stand that cliche one more time!" I explained that the portraits are all the famous cliche paintings that everybody knows. You look at the last one and say, "This is my mother—doesn't she have an enigmatic smile?" So he caught on right away and told me we had to have "the Laughing Cavalier" as his uncle, Oliver Goldbug.

It was going to be Little Shop of Horrors again, where Peter Lorre worked for Vincent Price as his sort of slave around the place in this huge hockshop; and at night they would hear this haunted music, and it would be the gold bug dancing on the strings of the harpsichord doing the Gold Bug Rag. Peter Lorre kept the bug in a snuff box and stayed friends with it by giving it drops of Yugoslavian booze. The bug would sting or bite people and turn them into gold, which is a variation of Little Shop of Horrors and Bucket of Blood. And there were all these famous poses, too. There was a one-armed bandit and a little girl by the pool in the White Rock ad, and they offered the statues for sale. Then when the buyers tried to melt them down, they'd turn into flesh.

But the script was very long, over three hundred pages, and [Corman's partner and producer] Sam Arkoff was enraged. It never got made.

What did you do on Revenge of the Blood Beast, aka She-Beast?

I wrote that picture in three days to get an airline ticket for my girlfriend. [Griffith worked as screenwriter and second unit director.] That was originally a comedy about communistic Transylvania with Barbara Steele, Mel Welles, and Paul Maslansky, who played a cop and produced. That was shot in a couple of weeks, but there isn't much I can tell you about it. It's a cult film in Europe.

How did you end up working as a screenwriter on Barbarella?

[The actor] John Phillip Law was a friend of mine, and [the director] Roger Vadim was looking for another writer for Barbarella. John recommended me and [the producer Dino De Laurentiis] hired me. I stayed with Vadim and Jane Fonda in their house outside of Paris and worked on the script. They'd already shot some of the picture when I was called to work on it and had even temporarily scored it with Beatles music. It was really bad.

Why did Terry Southern get the screen credit?

He took the material from the French comic strip, but that's all he did. Then they hired fourteen other writers before they finally got to me. I didn't get credit because I was the last one. I guess I rewrote about a quarter of the film that was shot, then reshot, and I added the concept that there had been thousands of years since violence existed, so that Barbarella was very clumsy all through the picture. She shoots herself in the foot and everything. It was pretty ludicrous.

The stuff with [the actor] Claude Dauphin and the suicide room were also part of my contribution to the film. But the most fun was staying at their house and talking all night with Vadim about politics—it was during the Pueblo inci-

dent[*]—and talking with Jane all day about movies. At that time, she wasn't known for her politics or for being a good actress. The military invited her to entertain the troops in Vietnam, but she was planning to defect and entertain the Viet Cong. Everyone was looking at her and imagining her plowing through the jungle with the Viet Cong and what would have happened to her.

How did you get involved with Death Race 2000?

I came back from Europe and I called Roger [Corman] and he said, "I've got something for you." I looked at the script, which was by Robert Thom, and it was completely bizarre, unshootable, and crazy, but it did have a lot of interesting things in it. "You're asking me to change this?" I asked Roger. He and I were always having trouble over the bizarre things in my screenplays. He told me that since the script had been written by a bizarre person, he figured it took another one to fix it.

So we started from scratch.[**]There were some original things we kept out of our version: Frankenstein, I know, and those cars—another idea of Roger's—were added later. I met Paul Bartel, who was already set to direct it, and we reached a mutual conclusion that the film had to be a satire, somehow a political satire, because there was nothing else we could do with those cars.

Roger, however, wanted a straight, hard-hitting drama, so it was a conspiracy with Paul and everyone in the office at times to keep Roger from knowing. I worked on a long-lost and forgotten version that was very funny and extremely bizarre, but Roger found out about it and canceled the entire script. He was really enraged. So we started again on a much more modified, but similar, straight version, which Paul shot. He left out all the blood, so Roger hired me to be a second-unit director and put in all those blood bits. I told Paul that the way I would do them would be so absurd and so overstated that the film would still stay funny. It didn't happen in the case of Heckle and Hype. I fought with the producers over blood and gore versus comedy, and lost as usual.

I've heard that at one time Roger wanted to rev up the engine noises in Death Race and drown out most of the dialogue.

He does that a lot. He'd play up the sound effects or turn the music way down, so that it would sound very distant, and he'd play with the dialogue, too. He was very big on sound effects. Yeah, he played with Death Race and tried to get rid of as much comedy as possible.

Would you describe some of your second-unit work?

The picture was in the can, so I took the stuff and had to add a lot of action. I looked through the material and added to it in different places. For example,

* The Pueblo was a US intelligence ship captured allegedly within North Korean territorial waters in January 1968. The crew were held for eleven months, then released.

** Ib Melchior's story provided the basis for Death Race 2000's script.

the scene where Sylvester Stallone drives down to the end of the pier was changed. Originally, there was a man sitting in the outhouse with the top door open and the machine-gun car pulls up and there's a conversation with Stallone while this guy is still in the outhouse. A dumb conversation. Stallone backs up and knocks the outhouse with this guy in it into the river and drives on. There wasn't enough action in that for Roger, and you could see when the outhouse fell into the river that there was nobody in it.

I went back, got rid of the outhouse, cut around the outhouse, and had a fisherman sitting there and Stallone chase the fisherman up the river. There were bits and pieces of both scenes, but all of Stallone's dialogue was from the other scene.

Was it a successful film for Roger?

It did about two and a half million dollars, so it must have been.

How would you describe Roger Corman? At times, he is referred to as an idiot savant—part genius, part deranged person.

Deranged, yes. Genius, no. The genius that he might have had is gone. He used to be full of ideas and Freudian concepts, and he'd throw these things out to the writers and get them all hot. They would work like crazy, but he would have forgotten what he wanted to do. He was only interested in saving money, so his intellect ground down to almost nothing. When you see some of his crap, there are a few moments of interest. That wasn't true of some of the other shockers that were being made at the time. Those producers knew what they wanted, and that was pure garbage and no great loss. Roger's stuff was 99 percent garbage and I percent is of interest.

He did, however, show some technical skill as a director and his films are usually well paced.

He took everything out that wasn't fast and ruined every picture that way. In recent years, he has ruined all of his pictures, and they're losing money. They are incomprehensible. Did you see Smokey Bites the Dust? It went right through town without being seen.

Wasn't that film built around stock footage?

That's true. Roger hired me a few years before that, in 1977 or '78. It all started with a news broadcast. The police were complaining that Eat My Dust!, and other pictures like it, inspired kids to chase down the freeways and challenge the cops and run other cars off the road. There were lots of people blamed for this, and Sheriff Pritches called this Car Wars. As soon as the newscast was over, the phone rang, and it was Roger. "I want you to do a picture called 'Car Wars,' " he said, "using the stunts from five old New World pictures."

I wrote a script which wound up being called "Wham Bam, Merci, Madame." It was insane and used all the stunts in different ways. But Roger hated the script and never did the picture.

In 1983, however, he called again and offered me a lot more money than he ever had before. I guess I got flattered, and I went ahead and did it. He had Max

Ron Howard in Eat My Dust! written and directed by Charles Griffith.

Apple in Texas go ahead and write a script around all the wrecks and chases. But Max wasn't allowed to see the footage. It was too expensive to rent a Movieola and send Max prints or anything else, so he had only vague descriptions written down on what the stunts were—and nothing worked. So I made a lot of changes in it, and that made Roger angry. He tried to cut it just to the action of the old pictures, but he couldn't, because he needed all the distribution rights. Then he cut all the motivations and all the character development. It was a mess, a jumbled mess! The same thing occurred in Up from the Depths.

Wasn't Up from the Depths Corman's attempt to do a Jaws film?

Of course it was. He stole it from Jaws [1975], Jaws 2 [1978], and The Deep [1977]. It was written by a secretary at the office with the intention that I would polish it up.[*] I was hired to direct, but Roger wouldn't pay Writers Guild prices—he thinks the Writers Guild is in a conspiracy against him personally—so the idea was that I would use my director's perogative to polish up an impossible script.

* The credited scenarist of Up from the Depths is Alfred Sweeney. Griffith is listed as director only.

So I wrote a zany version called "Something Fishy" and the Filipinos [the producers and investors] were crazy about it. They made a funny-looking fish for it, and we were all set to go; but they sent the script to Roger, figuring he would love it, and of course, he hit his desk and told them to fire me and everybody else. They wouldn't fire me, so I still had to do the polish, but I did it just for action.

There was a lot of excitement to just go ahead and shoot it, but then the action didn't work because the Filipinos didn't work. The fish never worked once. It was supposed to attack people, to chew them up, and thrash all sorts of things, but it didn't do anything. I had a right-to-left fish and a left-to-right fish, and a fin and a head which would come across the ocean on huge bamboo rafts towed by outrigger canoes. It would take them two hours to cross the bay with this stuff. It never worked.

The speedboats never worked because the propellers were beaten up by the coral reefs. The underwater shots didn't work, because there were no lead weights to get people down. They were bobbing to the surface. And nobody would show up. You would get ballroom extras on the beach and beach extras at the ballroom. There weren't any American cars available because all American cars belonged to rich people who wouldn't rent them. It was great being there for six months.

I had a 106-minute rough cut that I sent back. When I arrive in LA, the next day, it [Up from the Depths ] was 75 minutes long. That was some of Roger's creative editing. I've never seen the picture. I just saw the black-and-white work print that I was working on. Smokey and Up from the Depths were the last two pictures that I did for Roger, and they were both so butchered that it has made it impossible for me to get work. Those pictures are so bad no one can sit through them.

What about Dr. Hecky1 and Mr. Hype?

That's my old friend Menahem Golan from Israel. I stayed at his house about ten years ago and worked on a couple of pictures that were never made. He told me to call him up if I wanted to make a picture, so I did. He wanted to make "Happy Hooker Goes to Hollywood," but it took my agent too long to negotiate, so it was already in the works with other people.

So Golan asked me what I wanted to do. I told him that I specialize in black comedies, and I had a list of things I wanted to show [the writerdirector] Francis Coppola. There were a lot of things on that list that were jokes and were not intended to be pictures. But one of the films on the list was "Dr. Feelgood and Mr. Hype," in which a hippie invents a new drug that turns everybody into advertising executives.

He said, "You want to make a funny Jekyll and Hyde? " I responded, "Sure." He gave me the go-ahead, but I had only three weeks to write it and to prepare the picture, one week of which was in [the actor] Oliver Reed's hands, four weeks to shoot, and two weeks to edit. It was terribly, terribly rushed for

a modern picture in color with lots of elaborate art direction and stuff. This cost $750,000 and Cannon couldn't release it. [The film was quickly sold to cable.]

Heckyl and Hype could have been a very good picture. Dr. Heckyl is a monster podiatrist. He is very humble and meek and helpful and nice to everybody. His attitude is that good-looking guys can get away with murder. Oliver was great as Heckyl. Wonderful. He played the part with a kind of New York accent and everything, but when he was Hype, he didn't know how to do it. . . . Reed played Hype as Oliver Reed, slow and ponderous. He didn't understand my interpretation, so the picture jars, and half the people get up and walk out.

What do you think of the violence in today's horror movies?

Hate it! I was one who did it in the years when we couldn't show violence. In The Undead, for example, I had a scene where we back somebody against a wall and the headman swings an ax cutting off the head and the body slides down the wall with blood spurting from the neck. The head stays on the ax blade against the wall. In the fifties, filmmakers couldn't do anything like that, so we were all frustrated in those years. But, boy, as soon as it started to appear on the screen, it made me sick. I don't want to do it or see it.

What are your future projects?

I'm writing one called "Out of This World," which is a very large-scale science fiction film. I can't tell you about it because the idea is the best part so far. New World wanted me to come back and write a sword-and-sorcery picture, but they didn't want to pay me, and I wasn't going to do it for nothing. Let's see, there's "The Real McCoy" and "Oy Vey, My Son Is Gay," which will be the Jewish La Cage aux Folles for Cannon. But that's all I can tell you about now.