Terry Southern: Ultrahip

Interview by Lee Hill

From 1962 to 1970, Terry Southern was the screenwriter who most embodied the sixties zeitgeist. He was an icon who entered the film world with underground cult status as the writer, behind Candy (co-written with Mason Hoffenberg), Flash and Filigree, The Magic Christian, and Blue Movie. He was directly involved in the making of Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider, two films that neatly bookend and encapsulate the apocalyptic obsessions of the hothouse decade. His contributions to the films The Loved One, Casino Royale, The Collector, Don't Make Waves, Barbarella, The Cincinnati Kid, The Magic Christian, and End of the Road varied from on-the-set script surgery and uncredited rewrites to hands-on coproduction.

Born in Alvarado, Texas, on May 1, 1924, Southern served in the US Army during World War II. He completed a bachelor of arts degree in English at Northwestern University in Chicago and attended the Sorbonne on the GI Bill. During the fifties, he perfected a personal brand of black humor and irony through his novels and the short stories and sketches found in the 1967 collection Red Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes. It was a sensibility that allowed Southern to move through several worlds at once. He socialized with the Beats downtown and the Paris Review crowd uptown. Despite his hipster aura, he made friends easily. His close friends in his pre-Hollywood days included Kenneth Tynan, Henry Green, Lenny Bruce, and Alexander Trocchi.[*]

By the early sixties, Southern came to the attention of two other cultural heroes, the director Stanley Kubrick and the actor Peter Sellers (there is a little bit of Terry Southern in Sellers's interpretation of Claire Quilty in the film Lolita ). The unique brand of epic satire in Southern's novels made him an

* Alexander Trocchi, the Scottish novelist and iconoclast, wrote Cain's Book (New York: Grove Press, 1960).

ideal candidate to complete the troika of sensibilities that made Dr. Strange-love arguably one of the greatest films ever made.

The wide distribution of Dr. Strangelove and the mainstream publication of Candy in 1964 fueled a highly successful eight-year stretch for Southern as a screenwriter. He abandoned the "Quality Lit Game" and embraced the possibilities of film with a passion unusual in literary circles. The response of the international film community was mutual. During this heady period, Southern worked with or was courted by, to name a few, the directors Tony Richardson, Alexander Mackendrick, Norman Jewison, Peter Yates, Jean-Luc Godard, Roger Vadim, Joseph McGrath, Mike Nichols, Richard Lester, Otto Preminger, and Jerry Schatzberg.

Dr. Strangelove, Southern now concedes, was his best experience working with a director. Southern was often hired to "do a Strangelove" on other scripts, but his skill as a screenwriter was broader than that. Easy Rider would lack much of its punch without the George Hanson character, inspired by Southern's love for William Faulkner's writing and the small-town lawyer, Gavin Stevens, who runs through Faulkner's novels. Hanson as played by Jack Nicholson provides the film's moral center. And despite its garish internationalcoproduction quality, Barbarella still amuses because of the Candy -like plotting and Jane Fonda's intuitive feel for the gentle joke in such Southern dialogue as, "A lot of dramatic situations begin with screaming." In Southern's two most underrated films, The Loved One and End of the Road, he had a role almost equivalent to that of codirector. The wild and overreaching structure of these metasatires holds up surprisingly well in the play-it-safe nineties, and both films are overdue for serious critical reevaluation.

In the seventies and eighties, Southern continued to write a screenplay a year, but none was produced.[*] Aside from his 1970 novel, Blue Movie, his most notable efforts during this period were his work on the 1981–1982 season of Saturday Night Live for the program's executive producer Michael O'Donoghue and The Telephone, a troubled 1988 collaboration with Rip Toen and Harry Nilsson, starring Whoopi Goldberg. Having had the privilege of reading scripts like "Grossing Out," an original commissioned by Peter Sellers, and his adaptation of Harry Crews' Car (New York: Morrow, 1972), I can only speculate that increasingly retrograde studio decision making in the nineties accounts for their unproduced status.

* While a complete list of unproduced projects cannot be listed for space considerations, it should be noted that, despite Southern's lack of on-screen credits after 1970, he remained a prolific screenwriter. Aside from the projects mentioned in this section, he worked on, to name a few, a script about Hermann Göring for a Swedish producer, an original called "Honky Tonk Heroes" for Rip Torn, and "Floaters," a script for Kubrick's former partner James B. Harris.

Terry Southern in Salisbury, Connecticut, 1995.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

One of his most recent projects, with the photographer Peter Beard, was a dark meditation on conservation called "End of the Game."[*] He also taught a new generation of screenwriters in a graduate seminar at Columbia University in the last years of his life.

Like the surrealist billionaire in his classic novel, The Magic Christian, Southern was a grand guy in person. Shy and reserved upon first meeting, he opened up when he relaxed. His expansive wit and generosity, along with a remarkable gift for mimicry, surfaced continually in our conversations. This

* "End of the Game" is based on Beard's book-length photo essay, which depicts the decline of the elephant safari in Kenya, and explores the pros and cons of conservation polices in the region, first published in 1965 (New York: Viking).

interview was conducted in person at Southern's home in Connecticut and by mail during 1993 and 1994.[*]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Southern makes cameo appearances as himself in The Queen, Cocksucker Blues, The Man Who Fell to Earth, and Burroughs.

Television credits include The Emperor Jones (1958, adaptation), Stop Thief! (1976, teleplay), and Saturday Night Live (1981–1982, staff writing).

Novels include Flash and Filigree, The Magic Christian, Candy (with Mason Hoffenberg), Blue Movie, and Texas Summer. Other books include Red Dirt

* This interview was completed shortly before Terry Southern's death. En route to his screenwriting class at Columbia, Southern collapsed and was rushed to St. Luke's Hospital. He died on October 29, 1995, from respiratory failure at the age of seventy-one. In one of many tributes, Bruce Jay Friedman, a longtime friend and fellow writer said that, while most "writers coexist uneasily, this observation did not apply to Terry Southern, who, for all his dark, satirical genius, was the most generous of men."

Marijuana and Other Tastes, Writers in Revolt (coedited with Alexander Trocchi and Richard Seaver), The Log Book of "The Loved One," The Rolling Stones on Tour—Log Book, and The Early Stones: 1962–1973.

Academy Award honors include Oscar nominations for Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for Dr. Strangelove and for Best Story and Screenplay Based on Material Not Previously Published or Produced for Easy Rider.

Writers Guild honors include Best Written American Comedy for Dr. Strangelove.

Dr. Strangelove; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

What was the status of the Dr. Strangelove script before Stanley Kubrick decided to hire you in the fall of 1962?

When Kubrick and Peter George first began to do the script, they were trying to stick to the melodrama in George's book, Red Alert [published under the pseudonym "Peter Bryant" (New York: Ace Books, 1958)].[*] There was an outline. They didn't go into a treatment but went straight into a script. They had a few pages and in fact had started shooting, but in a very tentative way. Kubrick realized that it was not going to work. You can't do the end of the world in a conventionally dramatic way or boy-meets-girl way. You have to do it in some way that reflects your awareness that it is important and serious. It has to be a totally different treatment, and black humor is the way to go. That was Kubrick's decision.

When you first got together with Kubrick, did you start changing the tone of the script right away?

Yeah, after the first day, at our first meeting, he told me what the situation was. All those things that I've told you were his very words. "It's too important to be treated in the conventional way. It's unique! The end of the world is surely a unique thing, so forget about the ordinary treatment of subject and go for something like a horror film." He decided to use humor. The flavor that attracted him in my novel The Magic Christian could be effective in this new approach. He would talk about the mechanics of making it totally credible and convincing in terms of the fail-safe aspect and then how to make that funny. And the way you make it funny, because the situation is absurd, is by dealing with it in terms of the dialogue and characters.

I'm curious about the day-to-day working relationship with Kubrick as you wrote the film from the preproduction period through the actual shooting.

* Peter George, a former Royal Air Force officer, published Red Alert in 1958, and collaborated on a straight adaptation of his book with Kubrick during the early stages of the project.

Well, after my first day in London when he told me what he had in mind, I got settled into a hotel room not far from where he lived in Kensington. That night, I wrote the first scene, and then he picked me up at four-thirty the next morning in a limo. The limo was a big Rolls or Bentley. We rode in the backseat with the light on. There was this desk that folded down. It was very much like a train compartment. It was totally dark outside. If it got light, we would pull the shades down. He would read the script pages; then we would rewrite them and prepare them for shooting when we got to the studio, which was about an hour to an hour-and-a-half drive depending on the fog.

Kubrick is notorious for his organizational mania.

Yes, he loved nothing so much than to go into stationery stores and buy gadgets and organizational aids.

You hear all these fantastic stories about how Kubrick lives. Did you visit his home much when you were in London?

Yes, several times. He has a castlelike structure, a grand old mansion, which has this two-projector screening room. It has electric fences and security devices. It has everything except a moat. He's super private because he lives for his children. He lives in comfort and luxury in almost total isolation.

Peter Sellers was going to play all four parts originally, including the Texan bombardier. I understand you coached Sellers on his accent.

The financing of the film was based almost 100 percent on the notion that Sellers would play multiple roles. About a week before shooting, he sent us a telegram saying he could not play a Texan, because he said it was one accent he was never able to do. Kubrick asked me to make a tape of a typical Texan accent. When Sellers arrived on the set, he plugged into this Swiss tape recorder with huge, monster earphones, and listened to the tape I made. He looked ridiculous, but he mastered the accent in about ten minutes. Then Sellers sprained his ankle and couldn't make the moves going up and down the ladder in the bomb bay. So he was out of that part. The doctor told him he couldn't do it. Then it was a question of replacing him. Stanley had set such store by Sellers's acting that he felt he couldn't replace him with just another actor. He wanted an authentic John Wayne. The part had been written with Wayne as the model.

Did Kubrick ever try to get Wayne to play the role?

Wayne was approached, and dismissed it immediately. Stanley hadn't been in the States for some time, so he didn't know anything about television programs. He wanted to know if I knew of any suitable actors on TV. I said there was this very authentic, big guy who played on Bonanza, named Dan Blocker. Big Hoss. Without seeing him, Kubrick sent off a script to his agent. Kubrick got an immediate reply: "It is too pinko for Mr. Blocker." Stanley then remembered Slim Pickens from One-Eyed Jacks [1961], which he [had] almost directed for Marlon Brando, until Brando acted in such a weird way that he forced Stanley out.

George C. Scott and Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove , directed by Stanley Kubrick.

When Pickens was hired and came to London, wasn't that the first time he had ever been out of the States?

Yes, in fact it was the first time he had ever been anywhere outside the rodeo circuit as a clown or the backlots of Hollywood. Stanley was very concerned about Slim being in London for the first time and asked me to greet him. I got some Wild Turkey from the production office and went down to the soundstage. It was only ten in the morning, so I asked Slim if it was too early for a drink. He said, "It's never too early for a drink." So I poured out some Wild Turkey in a glass and asked him if he had gotten settled in his room. "Hell, it doesn't take much to make me happy. Just a pair of loose shoes, a tight pussy, and a warm place to shit." One of Kubrick's assistants, a very public-school type, couldn't believe his ears, but went "Ho, ho, ho" anyway.

Finally, I took Slim over to the actual set where we were shooting. I left him alone for a few minutes to talk to Stanley. While we were standing there talking, Stanley went, "Look there's James Earl Jones on a collision course with Slim. Better go over and introduce them." James Earl Jones knew that Pickens had just worked with Brando. Jones was impressed and asked Pickens about the experience of working with Brando. "Well, I worked with Marlon Brando for six months, and in that time, I never saw him do one thing that wasn't all man and all white." Slim didn't even realize what he was saying. I glanced at James Earl Jones, and he didn't crack [a smile]. Slim replacing

Sellers worked out well because, unbeknownst to me at the time, the actor that was playing the copilot [Jack Creley] was taller and stockier than Sellers. Whereas Slim was about the same size [as the copilot] and more convincingly fulfilled the intention of this larger-than-life Texan.

To what extent did Peter Sellers' improvisation depart from the shooting script?

It was minimal. It wasn't like Lolita, where he improvised a great deal. His improvisational bits in Strangelove were very specific. One scene that comes to mind is when [Sterling] Hayden goes into the bathroom to kill himself, Peter's lines are: "Oh, go into the bathroom and have a brushup . . . good idea." Sellers changed that to: "Splash a bit of cold water on the back of the neck . . .," which is more of a British thing. That was good.

What was Columbia's reaction to this subversive black comedy that the studio had helped to finance?

Columbia was embarrassed by the picture and tried to get people to see Carl Foreman's The Victors instead. At the time we thought we were going to be totally wiped out. People would call up the box office and be told there were no seats for Strangelove and asked if they would like to see The Victors instead. Gradually, the buzz along the rialto built word of mouth in our favor.

Wasn't there some falling-out between Kubrick and yourself over screen credit following the film's release?

Stanley's obsession with the auteur syndrome—that his films are by Stanley Kubrick—overrides any other credit at all. Not just writing but anything. He's like Chaplin in that regard. That's the reason why he rarely uses original music in his films. [Since I had] written this great best-seller, Candy, which was number one on the New York Times best-seller list for something like twenty-one weeks, my reputation eclipsed Stanley's; so I got total credit for all the Strangelove success in Life, the New York Times, and other publications. The credit I was getting was just so overwhelming and one sided that naturally Stanley was freaking out. He took out an ad in Variety saying I was only one of the three writers on the film, the other two being Peter, George, and himself. He just lashed out. But it was like an overnight thing. I wrote a letter to the New York Times explaining that there was no mystery involved, and that I was brought in to just help with the screenplay.

The Loved One and the Cincinnati Kid (1965)

After Dr. Strangelove, you worked on The Loved One and Cincinnati Kid, two films produced by John Calley and Martin Ransohoff. What can you tell me about those experiences?

The Loved One was the most underrated film I've worked on. However, it has recently been released on videocassette and will finally be seen and, pre-

sumably, recognized. The cinematography by Haskell Wexler should have received an Academy Award. Everyone who knows anything about film agrees on that. The cast, which included John Gielgud and Rod Steiger, is one of the finest ever assembled. And working with Tony Richardson was extraordinary. He had just come off Tom Jones [1963], which won every award possible and made everyone connected with it a fortune—and yet such is the total sleaze and corruption of the studios that MGM refused to renegotiate his contract and made him abide by his pre-Tom Jones commitment to The Loved One for a minuscule fee. They thought they were being shrewd. Well, Richardson was so completely pissed off at them that he cast an American actor, Robert Morse, to play an English poet—at a time, when Tom Courtenay, James Fox, and Albert Finney, to mention a few, were available—and he barred [the producer] Martin Ransohoff from the set. We started each morning in the production office by opening a magnum of Dom Pérignon. The dailies were shown at the screening room of the Beverly Hills Hotel, with plenty of canapés laid on. In other words, their shrewd avarice cost them a pretty penny in the end.

Sam Peckinpah was the original director of The Cincinnati Kid. There is a sequence in the beginning where Slade, a wealthy southerner played by Rip Torn, is at home with his wife and two children. He is shown to be a sanctimonious family man. In a subsequent scene, he is shown in bed with his mistress. Well, it was obvious that the full irony of his hypocrisy, in this citadel of southern virtue, New Orleans, could only be attained by her being black. So that's how it was written, and that's how it was shot with Peckinpah of course in enthusiastic agreement. When the producer saw the dailies, he freaked. "We're not making a message picture," he said and replaced Peckinpah pronto with Norman Jewison, who said something like "Hey, you guys must have been nuts to try that!"

It may have balanced out though, because there's a scene in the movie where the Kid [Steve McQueen] is very depressed because his girl [Tuesday Weld] has just left, and he's trying to get his head together for the big game with the Man [Edward G. Robinson]. Norman said, "Okay, let's create an atmosphere of really devastating loneliness. Maybe Steve walking along an empty street. You know, putting an emphasis on his solitary situation. Think that will do it?" "Yes," I said, "if it's at night." That gave Norm pause. "A night shoot? Very expensive, Ter. Well, I guess we can manage it." "Well, if you really want to max it for loneliness," I said, "it really should be raining as well." "A night shoot in the rain? Holy Christ!" So there we were with a couple of blocks in midtown New Orleans cordoned off, at night, with rain machines letting it pour from the roofs of several buildings. Of course, the producer, Big Mart Ransohoff—the guy who had fired Peckinpah—freaked out completely. "Are you guys out of your gourd?" He kept shouting, "You're killing me, you're killing me!"

The British Film Boom

You spent a lot of time going back and forth to London during the height of the British film boom.

After Strangelove, I started working pretty quickly on an adaptation of [the novel by John Fowles] The Collector [Boston: Little, Brown, 1963].

Did you stay in England for that?

Yeah, although I quit before the shooting began. The two American producers [Stanley Mann and John Kohn] insisted on finding a way to save the girl [at the end of the story]. At the end of John Fowles' novel, the heroine dies of pneumonia after trying to escape in a rainstorm. Changing that didn't even seem like a possibility. It sounded like a stupid idea. I was not comfortable changing the ending, because of my admiration for Fowles' novel. I even wrote a letter to the London Times protesting this change, and it had some effect on the producers, which gave me a bit of satisfaction. Then they said, "We've been thinking about it. Maybe the real message is that art can triumph over an asshole like the collector." After showing his complete nerd-jerk-nowhere-man creepiness, I contrived to have her escape by outwitting the collector through her art [the girl is an art school student] and ultimately to prevail. So I wrote a couple of scenes where Samantha Eggar was working with a papier mâché sculpture in her cell. I set up a pattern whereby Terence Stamp would open the door of this room and look in very cautiously to make sure she wasn't trying to escape, because a couple of times when he opened the door, she tried to dart out. He would say, "I want you to stand where I can see you from the other side of the room." She created this papier mâché likeness in such detail that it deceived him. He would open the door and look across the room and see "her," when she was, in fact, just behind the door. Because the sculpture was so artfully done, he fell for it. The scene was like Hitchcock. Then she locked the door behind her and [locked] him in her former cell. Years later, she would be seen having a picnic on a lovely day. "It's so lovely here in this pastoral sylvan setting; I can understand why you like to come here," her companion would comment. The camera would then pull away to reveal they are having a picnic just a few feet away from the cellar door. By this stage, they had gone too far back toward the original premise for them to use the new ending that I proposed.g

The making of Casino Royale was a fairly acrimonious affair with all the directors from John Huston and Robert Parrish to Joseph McGrath. You spent a fair amount of time as an uncredited writer on the film[*]

* Joseph McGrath, the Scottish director, who worked with Richard Lester on The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film, then directed for television, most notably the BBC series, with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, Not Only . . . but Also. Casino Royale was to have been McGrath's feature film debut, but the producer Charles Feldman hired, fired, and then rehired him along with four other directors—Robert Parrish, Val Guest, John Huston, and Ken Hughes—and the results were edited together. Other writers, credited and uncredited, included Wolf Mankowitz, Michael Sayers, Joseph Heller, Ben Hecht, and Billy Wilder. McGrath's other film credits include Thirty is a Dangerous Age, Cynthia, and The Bliss of Miss Blossom, and, or course, the adaptation of The Magic Christian. Southern and McGrath later worked on an unproduced film version of William Burroughs' Last Days of Dutch Schultz and a spoof about the Cannes Film Festival.

I received a call from Gareth Wigan, a famous British agent, who was representing me at the time. He had this call from Peter Sellers saying Peter wanted me to write some dialogue for him on this movie. Wigan said, "I think you can ask whatever you want, because the producer, Charles Feldman, wants to make it a blockbuster." There was a lot of heavyweight on that movie because of Orson Welles and Woody Allen. However, Woody Allen and Peter were such enemies on that film that I didn't really associate with anyone but Peter. An extraordinary thing happened. Because Woody Allen was having such a bad time on the picture, his agent came over to the Dorchester Hotel to speak to him one day. When he came into the lobby, he was dead sure he spotted his client Woody Allen at the newsstand reading a paper. The agent came over and said, "Hey, Woody, we're gonna fix that fucking Sellers, and he'll be off this picture." But it was actually Peter Sellers he was talking to. Sellers immediately realized that it was a case of mistaken identity and of course went right along with it, apparently giving a masterful impersonation of Woody Allen. He used to repeat this imitation with the grimace and glasses. The agent kept ranting for three or four minutes how Sellers should be fired and some specific things like "I've seen his contract, and I know how much he's getting, blah, blah, blah," and then he split. Peter was so irate—later he was amused—that he walked straight out the door and flew home to Geneva and announced he was taking a few days holiday. So this multimillion-dollar movie came to an abrupt halt. It was an incredible situation costing thousands a day. They tried to shoot around Peter in his big confrontation scene with Orson Welles in the casino. Welles was furious. They didn't even have all the actors in the master shot, just some stand-ins, and each day, they would shoot around whichever star didn't show up.

There were a lot of writers involved on that project. Can you remember which scenes you wrote?

Just the Peter Sellers stuff. I rewrote all his dialogue in the scenes he was in. I just rewrote with an eye to giving him the best dialogue, so that he would come out [of the film looking] better than the others. I earned an enormous amount for work which I essentially did overnight.

Where would you stay in England when working on a film?

I was staying at the Dorchester during Casino Royale. I stayed at a number of hotels. Writing on a contract for a major studio, you get the very best. I

would go back and forth on these over-the-Pole flights, where you would go from LA to London. I wrote a lot during those flights.

You spent a fair amount of time socializing with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and others in the scene associated with Robert Fraser's London art gallery.

I knew about Robert Fraser's gallery because friends of mine like [artists] Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Larry Rivers, and others would show there. Robert Fraser was an extraordinary guy. Kenneth Tynan lived on Mount Street near the gallery. He used to take me to a lot of places like that. Fraser's gallery became very common knowledge in the industry. One day, Tynan said I had to meet this friend of his, Colin Self, who had done this extraordinary piece of sculpture which was like the Strangelove plane. They wanted me to pose with it at Fraser's gallery. That was my first actual trip there. While I was there, Michael Cooper,[*] the photographer who took some pictures, said, "You must come over [to my place] for drinks. Mick and Keith are going to be there." Robert used to have this very active salon at his flat. So I went over and got to know them in a very short time. Christopher Gibbs, the antique dealer and production designer for Performance [1970], was part of the crowd at Robert Fraser's. Then there was Tara Browne, who was killed in the car crash John Lennon wrote about in "A Day in the Life." Sandy Lieberson, who was an agent who optioned Flash and Filigree and produced Performance, was there a fair bit. He was involved with the American film industry in London. I wasn't around during the actual shooting of Performance, but I heard a lot of talk about it from James Fox and his father, [the film and theatrical agent] Robin Fox.

Wasn't your old Paris buddy [the novelist] Mordecai Richler still living in London then?

He was in fact living there and so was [the director] Ted Kotcheff. We had these great poker games.

Did you meet the Beatles around the same time?

I met the Beatles at exactly the same time, because Michael Cooper was doing several of their album covers. He had that market sewed up.

Do you remember how they decided to choose your face for the cover of Sgt. Pepper?[**]

* Michael Cooper died in 1973, but his photographs of the period can be found in two wonderful books, The Early Stones; 1962–1973 (New York: Hyperion, 1992) with text by Terry Southern, and Blinds and Shutters (London: Genesis/Headley, 1990), both edited by his former assistant, Perry Richardson.

** In the upper left-hand corner of the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, Terry Southern wears big dark glasses, with Tony Curtis on his right, Francis Bacon just off to the left, and Lenny Bruce, Anthony Burgess, and W. C. Fields just above.

I was probably one of the few people they knew who wasn't an icon of a sort. Most of the other faces on the cover were historical choices. [Of all the Beatles] I am closest to Ringo. Ringo was a very good friend of Harry Nilsson. Through Ringo, I met Harry, who I became grand good friends with and later worked [with] on scripts like The Telephone for Hawkeye, a company that we formed.

Candy (1968)

Before Candy was directed by Christian Marquand, you were involved in the adaptation as a coproducer as well as writer.

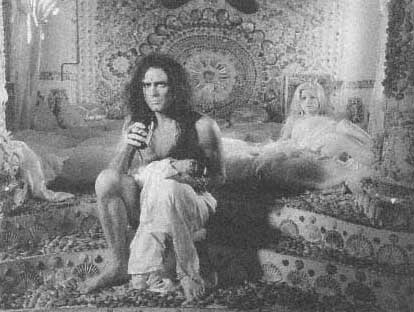

Yes, the first plan for Candy was for David Picker, who was the head of United Artists at the time, to produce and Frank Perry to direct. Perry had just come off David and Lisa, [1963], so he was big. We were going to get Hayley Mills to play Candy. She was perfect. [However,] John Mills, her father, wouldn't let her do it. We were still in the process of trying to persuade him to let her do it when David Picker lost his position. Then, my good friend Christian Marquand, the French actor who was trying to break into directing

Marlon Brando and Ewa Aulin in the film Candy , based on Terry Southern's novel.

and was certainly competent enough to direct at the time, begged me to let him have the option for two weeks for nothing, so he could put a deal together. So I did, and sure enough, Marquand immediately put Brando in the cast because Brando was his best friend. They were lifelong friends to the extent that Brando named his first son after Marquand. So on the basis of getting Brando, he was able to add Richard Burton and having gotten those two, he was able to get everyone else. Then, he disappointed me by casting a Swedish girl [Ewa Aulin] for the lead role, which was uniquely American and midwestern. He thought this would make Candy's appeal more universal. That's when I withdrew from the film. The film version of Candy is proof positive of everything rotten you ever heard about major studio production. They are absolutely compelled to botch everything original to the extent that it is no longer even vaguely recognizable.

Buck Henry wrote the final screen adaptation. Did you know him at all?

I didn't know him at all at the time. I wasn't even aware that he had written a script of Catch-22. I just thought he was the creator of Get Smart.

Did you look down on TV writers at the time?

Well, how would you feel? I mean, situation comedy! What could possibly be creatively lower than that? It has nothing to do with TV versus film. It's just that situation comedy is mass produced and not something that has much to do with writing.

Barbarella (1968) and Easy Rider (1969)

In the fall of 1968, you went to Rome to work on Barbarella.

Yes, I stayed there during the shoot at Cinecitta. I was living at the top of the Spanish Steps in a good hotel there. It was a good experience working with Roger Vadim and Jane Fonda. The strain was with Dino De Laurentiis, who produced the picture. He was just this flamboyant businessman. His idea of good cinema was to give money back on the cost of the picture before even going into production. He doesn't even make any pretense about the quality or the aesthetic.

Vadim wasn't particularly interested in the script, but he was a lot of fun, with a discerning eye for the erotic, grotesque, and the absurd. And Jane Fonda was super in all regards. The movie has developed a curious cult following, and I am constantly getting requests to appear at screenings at some very obscure weirdo place like Wenk, Texas, or a suburb of Staten Island. Around 1990, I got a call from De Laurentiis. He was looking for a way to do a sequel. "On the cheap" was how he expressed it, "but with plenty action and plenty sex! " Then, he went on with these immortal words: "Of course, Janie is too old now to be sexy but maybe her daughter." But nothing, perhaps fortunately, came of it.

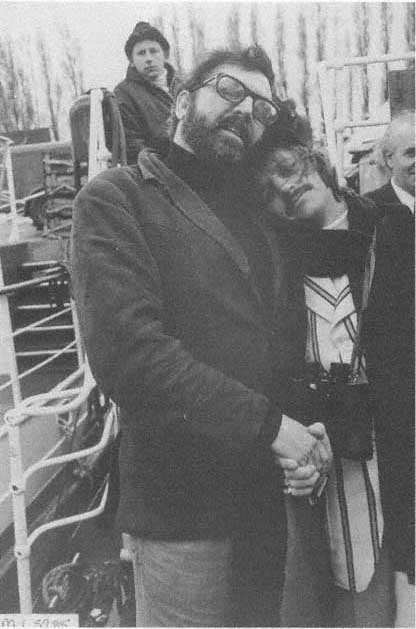

Jack Nicholson in the jail scene in Easy Rider , directed by Dennis Hopper.

Wasn't it during the making of Barbarella that you first began working on Easy Rider?

Yes. Very early on it was called "Mardi Gras" to identify it. The first notion was that it would entail barnstorming cars, stunt-driver cars, which do flips and things—a troupe who play a few dates and places, and eventually get fed up with that, so they make this score—but that just seemed too unnecessarily complicated. So we just settled for the straight score of dope, selling it, and leaving the rat race. We forgot about the commonplace thing of daredevil drivers. Finally, we forewent any pretense of them doing anything else other than buying cocaine. We didn't specify that it was cocaine, but that's what it was. They go to New Orleans to sell it. Then, once they got their money, they ride to coastal Florida or some place like Key West where they could buy a boat cheap—not in New Orleans, because it would be too expensive. That was basically the story, which I then started to flesh out after our initial script meetings.

Did they actually do some kind of formal writing, or was it mainly in the form of tossing around ideas at story conferences?

Story conferences, mainly.

So, when you worked with Hopper and Fonda at your office and during the New Orleans shoot, you would just talk the story out and then go off and physically write the pages?

I did all the writing on it. They just had the idea in the beginning of the two guys making a score and using the money to buy their freedom from the rat race of America. Their pilgrimage on the road. That was all they had. No dialogue.

So you were the only one doing the actual, physical writing on it?

I did the only writing on it. Peter Fonda was the only working actor in the group. Dennis wasn't really into acting at this time. He was a photographer. He had acted a long time before and had been a child actor. He was in Sons of Katie Elder [1965]. Peter Fonda had been in several of these really low-ball series of biker movies for AIP [American International Pictures]. He had a contract for one more in a three-picture contract. Dennis had this idea they would do instead of doing one of their typical B-picture dumbbell movies: under the guise of doing a biker movie, they could maybe pull off a movie that might be more interesting, [and] Dennis would be able to make his debut as a director in one fell swoop. It seemed possible under these auspices, whereas he couldn't get arrested ordinarily. Under the setup where Peter Fonda owed AIP this picture, it would be possible to get this different approach in under the wire. He persuaded Peter to go along with this, "We'll get Terry to write the script!" I had this good reputation off of Dr. Strangelove and Candy.

How did Easy Rider end up at Columbia?

That was through this guy [the producer] Bert Schneider, who made a deal for the distribution rights. He wasn't involved during the production. He made some kind of deal with Dennis and Peter. Peter was the nominal producer. So that was the situation when they came by my place in New York. They said, "We want you to write this, and we're going to defer any money in exchange for splitting 10 percent three ways." For a variety of complicated business reasons, I wasn't in a position where I could defer; so they said, "You can get $350 a week for ten weeks in lieu of that." So I did it that way. So I never had a piece of the film, which turned out to be very lucrative.

Anyway, they told me the basic notion of two guys who were fed up with the rat race and commercialization of America. So, in order to get out of it, they're going to make this score and then head to Galveston or Key West, and buy a boat and take off. The story would involve a cross-country trip and the various adventures that could befall them. The idea of meeting a kind of a straight guy, which turned out to be the Jack Nicholson role, was totally up to me. I thought of this Faulkner character, Gavin Stevens, who was the lawyer in this small town. He had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford and studied at Heidelberg, and had come back to this little town to do whatever he could there. So I sort of automatically gave the George Hanson character a sympathetic aura. I wrote the part for Rip Torn, who I thought would be ideal for it. When

shooting began, we went to New Orleans and Rip was going to come, but he couldn't get out of his stage commitment in a Jimmy Baldwin play, Blues for Mr. Charlie. At the time, it seemed like there was a possibility he might. We could shoot his part in a few days, and he would still be able to make this theatrical commitment. It wasn't a big part. [The Baldwin play] was a Greenwich Village production and very little bread for him. He was doing it because he felt committed to it. Because he's very much that kind of guy. So he missed the role of a lifetime. And Jack Nicholson was just on the scene, always around. He was a good choice, because he had that sympathetic quality.

How did you feel after the release of Easy Rider, when in interviews Dennis and Peter kind of downplayed the fact that you had written the screenplay. It seemed almost like an attack of amnesia on their part.

Well, vicious greed is the only explanation. And desperation for some ego identity material, because neither one had much of that. Whereas for me, I was filled with an abundance of praise and things.

You said you wanted to talk more about Easy Rider because of a possible lawsuit regarding your rights to it.

I don't want Dennis to do [Easy Rider II ] without notifying me or anything, because in order to get their names [Hopper's and Fonda's] on Easy Rider I had to call the Writers Guild to say it was okay. For a director and a producer to be named on the writing credits is practically unheard of. Since there has been so much coercion, bribery, and so on by directors in the past, tacking themselves onto the credits, nowadays it's an automatic arbitration. And so, I received this phone call from Peter saying, "Well, we've got this print. I think we've got a nice little picture here. Dennis and I want to get our names on the writing credits, but in order to do that, you'll have to notify the Writers Guild to say that it's all right."

Did you think it was a fair request at the time?

It wasn't fair, but it didn't matter to me at the time because I was ultrasecure. I had Candy and Dr. Strangelove. I said, "Sure, that's fine." I didn't mind. So I spoke to the Writers Guild. They were a little surprised. They said, "Well, those guys aren't even members of the Writers Guild. They're not really writers, are they?" I said, "Yes, that's true, but you don't have to be in the Writers Guild to write something," although you are supposed to be in order to participate [in the profits, residuals, et al.].

A lot of people still seem to think Easy Rider was this completely improvised film, but looking at the shooting script, I was surprised to find even the graveyard hallucination scene was completely scripted out. Why did Peter and Dennis take the lion's share of the credit on that film?

Yeah, neither of them is a writer. It's often the case with directors that they don't like to share credit, which was the case with Stanley. He would prefer just "A Film by Stanley Kubrick," including music and everything. Aside from Kubrick, other directors I worked with rarely did anything on the script.

End of the Road (1970)

The director of End of the Road, Aram Avakian, and you were co-conspirators and friends since meeting in Paris in the late forties?

He had a kind of Renaissance-man quality so he just got interested in films.

He edited Jazz on a Summer's Day [1959 ].[*]Was that his first gig?

Yeah, he started work as an apprentice for Bert Stern, who was the director. Aram was invited to direct a film called Ten North Frederick Street [based on the John O'Hara novel]. Ten North Frederick Street was going to be his big chance. Something went wrong there. Then he met some producer who was powerful enough to get him another directing job. The movie the guy got him was called Lad: A Dog, in which the hero was a dog. You can imagine what a challenge that would be. Avakian did some work on the script. He used to come by and discuss things. It reached the state where at the end of the movie, the dog, Lad, was getting married. The story called for a kind of wedding between the dog, this Lassie-type collie, and some sort of very pampered dog of the same breed. Of course, Aram insisted that it shouldn't happen like that, and instead Lad should run off with a mongrel dog. Aram said if he could get away with that, the film would work. What happened was he got fired because the studio wouldn't go along with that.

End of the Road came about through a mutual friend, Max Raab, who was a very nice guy, whose line of business was women's clothing shops, a certain kind of casual wear. Very expensive, very high fashion. Raab wanted to get into show business, and he was very knowledgeable about movies. He said, "Look, you guys find a property, and I'll get hold of about $300,000."

I had just read this John Barth novel [End of the Road (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1958)]. Aram had read it on my recommendation. We simultaneously agreed that it was a good story, and that it would make a good movie. So we got an option on it, wrote a treatment, and showed it to Max Raab—who hated to be called Max A. Raab, being very Jewish. (Laughs. ) So he agreed. We got the money together and hired Steve Kestern, who had worked with Arthur Penn, as our production manager.

Dennis McGuire has a cowriting credit along with you and Avakian. What was his role?

He was some guy who, unbeknownst to us at the time, had an option on the Barth novel. We couldn't buy him out, so we had to cut him in on the writing fee.

Since he wasn't active in the writing of the shooting script, was crediting him a conciliatory gesture on your part?

* A documentary of the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival.

Yeah. In the late summer of 1968, we scouted locations around East Canaan in Connecticut and Great Barrington, Massachusetts. We found this fantastic old button factory in Great Barrington, which was perfect as a soundstage. That's how End of the Road got started. Oh yes, one of the interesting things was that we needed a good director of photography. We couldn't afford a regular one, so Aram had this idea of scanning commercials and getting a director of commercials who wanted to break into features. We started to look at these reels of guys who made commercials, and we noticed one who was much better than the others. We hired the director, who turned out to be the great Gordon Willis.

You were also fortunate to cast people like James Earl Jones, Stacy Keach, Harris Yulin, and Dorothy Tristan. The film has some very interesting effects and a startling opening montage.

We tried to give the film a full-on sixties flavor—student unrest and so on—which seemed inherent in the book. A very good book, and, I like to believe, a most faithful adaptation, with a little something extra in the form of Doctor D's [played by James Earl Jones] theories.

The Magic Christian (1970)

Your next big project was The Magic Christian. That project had been in gestation for about four or five years before shooting started in February of 1969.

The way it evolved was that Peter Sellers and Joe McGrath had been working together with Richard Lester on his Running Jumping and Standing Still Film [1960], so they got to be good friends. McGrath had been working as an assistant to Richard Lester. McGrath wanted to direct something on his own. He asked Peter what would be a good movie to direct. And that turned out to be The Magic Christian. Peter had bought a hundred copies of my novel to give out on birthdays and Christmas. Joe McGrath thought it was a match made in heaven, so Peter immediately started to develop the property. Peter had a contract with some studio which had produced his last movie. He told them Christian was going to be his next movie and he wanted Joe to direct. Did they want to finance it, or did they want him to look somewhere else? Their first reaction was "Yes, we'll do it!"

Was it your idea to give Guy Grand a son, which, along with switching the location from America to England, was the major departure from the novel?

Well, that came about because the producers wanted to get what they called some extra box-office appeal. Peter had seen me hanging out with Paul [McCartney], I think, and said, "Well, Terry knows the Beatles. Maybe we can get one of them." Ringo had said that he would like to be in the movie. So I said, "How about getting Ringo?" I've forgotten who came up with the specific

On the set of The Magic Christian : Terry Southern and a certain Richard Starkey, O. B. E.,

a pop star of some note.

idea of having one of the Beatles as Guy Grand's son, Youngman Grand, but I was willing to try it.

I understand you completed the script with Joseph McGrath, but that he and Sellers and company made changes while you were busy with End of the Road.

When I finally made it to the set of The Magic Christian, I spent a lot of time doing damage control. It was probably due to Seller's insecurity or a manifestation of that. Although he loved the original script and it was the key to getting started, he also had this habit where he would run into someone socially, like John Cleese or Spike Milligan, and they would get to talking, and he would say, "Hey, listen, can you help me on this script?" They would come in and make various changes, sometimes completely out of character from my point of view. I found these scenes, a couple of which had already been shot, to be the antithesis of what Guy Grand would do. They were tasteless scenes. Guy Grand never hurt anyone. He just deflated some monstrous egos and pretensions, but he would never slash a Rembrandt—a scene which they had in the movie. There's a scene at this auction house, where, just to outrage the crowd or the art lover, Guy Grand and his adopted son bribe the auctioneer to deface this great painting. Guy Grand would never do that. It was gratuitous destruction; wanton, irresponsible bullshit which had nothing to do with the character or the statement. It was very annoying. They shot the auction scene and agreed to take it out for a time, but it stayed in the final cut. Peter did come around to seeing it was tasteless.

There was no dissenting opinion on the film.

No, Joe McGrath didn't dissent. He could have dissented at the time they were making these changes, because he was the director. He had a more disciplined sense of comedy than Peter, if not Peter's flaring strokes of genius. McGrath didn't have that much control, and he was so in awe of Peter that he wasn't able to resist him.

Towards the end of production, you shot the final scene with Guy Grand and his son persuading various passersby to wade into a tank full of manure and help themselves to money floating at the top of the mess [—the tank was] at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

Peter insisted we had to shoot that scene under the [real] Statue of Liberty. The producers resisted because of the expense of the trip. They were ready to shoot it there in England. So Peter, in a fit of pique and rage, said, "Well, I'll pay for it!" and then they said, "No, we'll pay for it!" We were going to fly first-class to New York and shoot the scene. Then Gail [Gail Gerber, Southern's companion since the midsixties], of all people, noticed this ad saying the QE2 [Queen Elizabeth II ] was making its maiden voyage. She said, "Wouldn't it be fun to go on the QE2 instead of flying?" Peter thought that was a great idea. He assumed that it wouldn't be any more expensive than flying first class, but it turned out to be much, much more expensive. Flying was like

$2,500 a person; but going in a stateroom on the QE2 was $10,000 a person, because there were all these great staterooms on the QE2. The dining room was beyond first-class. Like, really fantastic. Instead of eating in the ordinary first-class place, [we] had this special dining room. It was called the Empire Room. It was a small dining room with about six tables in it. That was another $2,000 right there. But the producers were committed to it.

Before we left, I'd introduced Peter to this Arabic pusher, who had given Peter some hash oil. Peter put drops of it on tobacco with an eyedropper, and smoked the tobacco; or if he had cannabis, he would drop the oil on that and smoke it. It was just dynamite. Like opium. Peter became absolutely enthralled. He couldn't get enough of it. It was very strong stuff. So we all went on this fantastic five-day crossing. The whole trip was spent in a kind of dream state.

So there was you, Peter, Gail, and Ringo?

Yeah, Ringo, his entourage, his wife, and some of the kids. We never saw the kids. They were usually with the nanny. There was also Dennis O'Dell, the producer, and his wife.

That trip must have cost, as Guy Grand would say, "a pretty penny."

Yeah, I saw the figures on it once. The crossing cost about twice as much as the shot. They didn't use the shot of the Statue of Liberty in the end.

In 1969 and 1970, you had three major films in release with your name attached to them. Was it a good situation to have that kind of momentum, or was that a complicated time because of controversies like End of the Road's X-rating?

Yeah, that [X-rating] didn't seem to help. Easy Rider did get a nomination, like Strangelove. It also won the Writers Guild Award [in its category] for that year. You would think you would have more leverage in a situation like that. I am sure that you are sensitive enough to imagine how not having certain projects get off the ground could feel. If there were anything to be gained from indulging that feeling, I would certainly pursue it. It just seems like a silly thing to think about, because it's self-defeating.

Some Unproduced Projects

You were involved in A Clockwork Orange with the photographer Michael Cooper around 1966. How did that project end up with Kubrick?

When Michael Cooper turned me on to that book [A Clockwork Orange ], I read it and said, "This is really good and so cinematic." I sent the book to Stanley, circa 1966, and said, "Look at this." He got it and read it, but it didn't appeal to him at all. He said, "Nobody can understand that language [Nadsat, the newspeak-type lingo Anthony Burgess created for his novel]." That was that. The whole exchange occupied a day. Still, I thought someone should make a movie of this book.

At one point, I was making so much money on movie projects that I needed someone to handle paying the bills. I got involved with this friend of mine, Si Litvinoff, who had produced some showbiz things in New York like off-Broadway theater. He did a couple of things for me as a lawyer. I showed him the book and told him how it would make a great movie. He said, "You have enough money. Why don't you take an option on it?" So I took a six month option on A Clockwork Orange [by Anthony Burgess (London: Heinemann, 1962)] for about $1,000 against a purchase price of $10,000 and some percentages to be worked out. I wrote a script, adapted it myself. I thought I'd show the book around, but meanwhile, I would have the script too. After I finished the script, I showed it to some producers, including David Puttnam, who was working with various companies like Paramount. He was one of the people who read the script and saw the cinematic possibilities of it. In those days, you had to get the script passed by the Lord Chamberlain [then British censor of film and theater]. When we submitted it to him, he sent it back unopened and said, "I know the book, and there's no point in reading this script, because it involves youthful defiance of authority, and we're not doing that." So that was that.

About three years later, I got a call from Stanley, who said, "Do you remember that book you showed me? What is the story on that?" And I said, "I was just showing it to you because I thought it was a good book, but later I took an option on it." He said, "Who has the rights to it now?" What had happened was that there was a renewable yearly option. I had renewed once, and when it came up for renewal for another thou[sand], I didn't have the money; so I told Litvinoff I was dropping the option. So he said, "Well, I'll take it out." Then he held the rights. So I told Stanley, "As far as I know, this guy Litvinoff has it." He said, "Find out how much it is, but don't tell him I'm interested." I tried to do that, but Cindy Decker, the wife of Sterling Lord, my agent at the time, found out about this inquiry of Kubrick's; so she passed the word on to Litvinoff and his friend Max Raab, who had put up the money for End of the Road. He and Raab sold it to Kubrick and charged a pretty penny for it. Around seventy-five thou[sand], I think.

Did Kubrick use much of your script at all?

Well, when I learned that he was going to do A Clockwork Orange, I sent him my script to see if he would like it. I got back a letter saying, "Mr. Kubrick has decided to try his own hand." It wasn't really a relevant point because it was an adaptation of a novel. You're both taking it from the same source.

You and Kubrick also shared the rights to [the novel] Blue Movie. When you decided to write the novel, you dedicated it to him.

He had in a way given me the idea for Blue Movie. One night, around the time of Strangelove, somebody brought a hard-core porn film to show at Stanley's house. They put it on. Very soon into the screening, Stanley got up and left the room. We watched a little more of it, then stopped the film. Later

Kubrick said, "It would be great if someone made a movie like that under studio conditions." I thought Kubrick would be the ideal person to direct such a movie. When I came back to the States, I started writing a novel based on this concept and would send him pieces of the book from time to time. I still have a great telegram from him saying, "You have written the definitive blow job!" in the scene with the Jeanne Moreau—type, Arabella.

Was he ever interested in directing Blue Movie?

No, when he first mentioned it, I assumed that he would be interested in directing it. But it turned out that he has a very ultraconservative attitude to most things sexual. Around 1974–75, John Calley, who was then president of Warner Brothers, decided to make a film of Blue Movie. A number of other people wanted to do it but always with the idea of compromising the work by having simulated sex. Calley, however, was convinced, as was I, that the first production of a full-on erection-and-penetration movie using big-name stars and a talented director, made under studio conditions, would be a blockbuster of Gone with the Wind proportions.

Calley was friends with Julie Andrews at the time, and he and Mike Nichols, who had been signed to direct, were able to persuade her—for love, art, and a lot of money—to play Angela Sterling, the heroine of the story. A fourteen million dollar budget, quite adequate for the time, had been secured, and everything was ready. Ringo Starr had held an option on the book but was quite ready to step aside now that there was an actual production ready to roll. He didn't want any participation. He just wanted to see the book made into a movie. Enter the villain of the piece: Ringo's lawyer—who shall remain nameless—in absolute hysteria, ranting about how he, the lawyer, was "going to look like a schmuck if the picture gets made, and we don't have a piece of it." John Calley and I were prepared to give him a piece, but it turned out that Mike Nichols wanted to retain all points, so he could use them to make deals with actors. That proved to be a deal-breaking stipulation.

Had you written an actual shooting script for Blue Movie?

Well, as soon as I became convinced that the film was for real, I started immediately, without even getting into a contract. I eventually completed a script, but the deals didn't go through. We were as close to a movie being made as I ever experienced or have ever heard of. There didn't seem to be any possible deal-breaking element. When it fell apart, it was just a total freak thing.

Did you try to develop anything else for John Calley after that?

He liked a story I had written called "You're Too Hip, Baby" about a white jazz aficionado who lives in Paris and goes to see the blacks in the clubs in Paris&astric; He had the idea of a screenplay set in Paris, dealing with those charac-

* "You're Too Hip, Baby" originally appeared in Esquire (August 1963) and was later included in Southern's classic anthology. Red Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes (New York: New American Library, 1967).

terms. That got as far as an outline, which I was paid for, but nothing further was pursued. When Blue Movie fell through, that was really the end of our relationship.

Calley was considered the hippest movie producer of the time because he was able to deal with the money guys yet maintain an active rapport with directors like Kubrick and Nichols.

Yeah. I doubt that Kubrick and Nichols would work with anyone else. I doubt if there were any other producers who were percipient, sensitive, and aware enough to be tolerated by Kubrick and Nichols.

Around 1972, you were at work on an adaptation of Nathanael West's A Cool Million with [the director] Jerry Schatzberg?

I had known Jerry Schatzberg since he directed Panic in Needle Park. [1971] He was the first person who expressed interest in A Cool Million [New York: Covici, Friede, 1934]. We finished a script, and he was trying to raise money.

Did he have anyone in particular in mind with the casting?

He was a good friend of Faye Dunaway's. So he had her signed up . . . not that he thought she was right for the film, but he thought she could generate interest. She understood that and went along with it because they were good friends. We didn't have any male actor. It was going to be someone like Timothy Bottoms as Lemuel Pitkin. The subtitle of the book is "The Dismantling of Lemuel Pitkin."

After The Magic Christian, did you still see Peter Sellers on a regular basis, or was it only during the time of "Grossing Out" [c. 1980] that you became involved with him again?

I saw him on a sporadic basis, which turned out to be pretty regular. There was nothing planned.

You and Peter started to work on "Grossing Out," a script about international arms dealing, after the success of Being There [1979]. Did you work on Being There at all?

No. Peter ran his lines by me one time.

Andrew Braunsberg, who produced Being There, was going to do "Grossing Out."

Yes. "Grossing Out" dealt with the Western nations selling arms to the Third World and exploiting these countries.

Was there a director lined up before Peter died?

No, but Hal Ashby expressed considerable interest. I had written a script.

You worked with Dennis Hopper on the "Junky" screenplay in 1977, &astric;and then there was the Jim Morrison screenplay, which Hustler publisher Larry

Junkie was originally published by Burroughs under the pseudonym "William Lee" (New York: Ace Books, 1953). When the book was republished under Burroughs' byline in 1977, it was retitled Junky. The unproduced script that Southern worked on was always called by the revised spelling.

Flynt wanted to produce in 1983. How has your relationship with Hopper evolved since Easy Rider?

Well, he's [Hopper] always said, "We're going to make that up to you," regarding Easy Rider. And while we were working on "Junky," I heard him say, "We want to make sure Terry has a good contract because he didn't get his share out of Easy Rider."

Wouldn't it have been easy for them to give you points after the fact?

Oh, yes.

What prevented them from doing that?

Well, I say vicious greed. That's the only reason.

What about "Junky"?

Well, "Junky" was something that Jacques Stem, also known as Baron Rothschild, who was a lifelong friend of Burroughs', optioned.&astric;Then Hopper and Stern commissioned me to write the screenplay. Hopper was going to play the part of Bill Lee, the junkie narrator of the novel, as well as direct. It turned out that Dennis wasn't that interested in making "Junky," and Stern didn't have enough money to produce the film, although he did have enough to option the book and finance the screenplay.

Did you actually finish a draft?

Burroughs, James Grauerholz [Burroughs' secretary], and I wrote a draft, which we showed to Stern [about which we asked] him if he had any criticisms or suggestions. Stern was trained as a physicist and was ultralucid, but he was also a decadent drug user. He had some kind of paralysis which left him wheelchair bound. He was living in Gramercy Park, while we stayed in a hotel uptown. Jacques had a hypodermic-type device taped to his wrist. All he had to do was tap this device, and he would get a jolt of speedballs. Jacques would say to us at our meetings, "See if you can work up some heavy thoughts? I have to get off!"

When you guys were writing "Junky," what was Dennis' function? Was he helping you write it?

No, he was just hanging out and hoping to direct it, but at the time, he was just higher than a kite. That was his preclean stage.

Both the book and script jump around quite a bit from New York to the rehabilitation center to Mexico and then back to the States. It's somewhat episodic. [The book] Junky treats drugs in a noncelebratory and nonjudgmental way. The book itself is a rare document.

Yes. Burroughs wrote some things for Lancet, the British medical journal, like a critique of a British doctor who had one of these remarkably successful

* According to Ted Morgan's biography of Burroughs, Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs (New York: Holt, 1988), Stern, a Harvard-trained physicist, raised $100,000 to hire Burroughs, Dennis Hopper, and Terry Southern to work on the ill-fated Junky adaptation in 1977

addiction cures using a drug called apomorphine. It's like morphine but is used to reduce the body's dependence on heroin. Apomorphine provided some protection, so that you wouldn't get this terrible sickness when you try to withdraw.

I gather apomorphine was similar to the methadone treatment.

Yes. One of the first scenes in the script deals with this guy who is coming to sell a package of army surretes. These are 3 cc ampoules of morphine which were in medical kits for soldiers on the front, so that if you got wounded, you could shoot one of these up. That was one of the things sold in trafficking in the forties.

You never actually finished a final script.

No. If Jacques Stern had taken it more seriously as a real project, instead of as a way to work out his relationship with Bill, it might have worked. There was an atmosphere of ultraparanoia between Jacques and Bill.

The Telephone (1988)

How did Harry Nilsson get involved in writing scripts?

Nilsson was a very creative guy. He had this story about a reporter who works for tabloids like the Enquirer or the Star, writing outlandish stories like "Headless Man Seen in Topless Bar." So we wrote a script called "Obits." Harry was able to finance the writing.

The Telephone was a collaboration with Nilsson that actually got filmed. I have always been curious about the story behind that.

We had this idea about an out-of-work actor who gets so into hallucinatory-type improvisations that he even makes up phone calls to himself. By chance, we were in the basement parking lot of the Chateau Marmont, and getting out of the car next to us was Whoopi Goldberg. We had seen her work and thought she might be right for the part.

Who were you thinking of originally?

Robin Williams. We wrote it with him in mind. We made this strenuous effort to get the script to him or at least talk to him on the phone. One night, by chance, we ran into him at the Improv [a comedy-improvisation theater]. He hadn't gotten the script, and then after a long time, we found out his manager didn't want him to do the film at all.

How did Rip Torn end up directing The Telephone?

Well, we needed a director, and I had seen some things Rip directed on stage. It just occurred to me that he could do it, and I didn't think there would be much to do, because it all takes place in a one-room apartment. It turned out Whoopi was a great admirer of Rip. When he and Geraldine lived on Twenty-second Street in New York, Whoopi was an unwed mother on welfare and living in that neighborhood. She would be walking to the welfare office to get her check and sometimes pass them in the street.

Was the shooting of The Telephone quick, or was it a long process?

Well, what happened was these big asshole producers told Whoopi that "this is a Whoopi Goldberg movie . . . ," so she could do whatever she wanted to do. Thus armed, she was able to ignore the script and just wing it. She's a very creative woman, and her improvisations were often good, but she had gotten involved because she really loved the script, and now she was suddenly making all these changes. So anytime she and Rip would get into an argument about a scene, she had this upper hand. After she did her improvisations, Rip would say, "Okay, let's do one for the writer." This went on and on through the production. I was on the jury at [the] Sundance [Film Festival] the year The Telephone was finished and took Rip's cut of the film there. I was ambivalent about it. I was too close to the film to be objective, but a number of people ended up liking the released film. [The New World version] is still selling well as a cassette at my local drug store.