Arnold Schulman: Nothing but Regrets

Interview by Pat McGilligan

Sometimes Arnold Schulman is a hard man to find because he has addresses on both coasts, and because there are long interludes of time when he forays into remote, underdeveloped areas. None of my efforts to locate him were working when Fred Roos, the producer of Tucker: The Man and His Dream, helped out, offering a long-standing phone number from his well-thumbed address book. I phoned, Schulman answered. A day or two later, by appointment I rang the doorbell of his Beverly Hills residence.

Wearing something kimonolike, he answered and ushered me into his home, outwardly contemporary in design but inside furnished with tasteful ancient and Oriental touches, right down to a Japanese room with pillows and panels and folding screens, where he does much of his writing. His candor and sense of humor made for instant rapport and for a long, sometimes digressive conversation about an impressive career that began in the 1950s.

He started out as an aspiring playwright, studying form and structure with Robert Anderson, Clifford Odets, and others. He learned to write in workshops while in his spare time dipping into the Method with Lee Strasberg, who directed his first play, My Fiddle Has Three Strings. He took on-the-job training as a writer for live television and worked on nearly seventy teleplays. His first play failed; however, Schulman was then beckoned to Hollywood, initially by the director George Cukor and the producer Hal Wallis. He then wrote the screenplay, based on his own Broadway play, for Frank Capra's feature film A Hole in the Head.

The sixties were Schulman's Hollywood heyday; the seventies, his nadir (for both hilarious and pathetic reasons); and the eighties, with A Chorus Line and Tucker, his magnificent comeback. In our conversation in 1991, we did not dwell very much on a current project of his that seemed a comparative long shot—an adaptation of Randy Shilts's nonfiction book And the Band Played On

(New York: St. Martin's, 1987), which deals comprehensively with the history, politics, and science of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). In the end, Band survived five years of development, twenty-three drafts, three directors, and all kinds of second-guessing. "I lived through every issue we dealt with in the movie—egos, greed politics," Schulman, who also coproduced Band, told the New York Times at the time of its first airing in September 1993. "It was a nightmare."

Schulman always insisted that he was writing And the Band Played On as a motion picture, and that the eventual sponsorship of the cable channel HBO was purely circumstantial. Schulman's credit on-screen and on posters is for the "screenplay," not the teleplay. In many ways, the film is the highpoint to

Arnold Schulman in Los Angeles, 1993.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

date of a career with more than a few bends, dips, and cartwheels. Schulman's sober, documentary-style, chronological treatment of the AIDS issue places the heterosexual, heroic medical scientist Don Francis (played by Mathew Modine) at the forefront of a multicharacter saga of disease sufferers and scientists (an all-star cast that includes Ian McKellen, Richard Gere, Steve Martin, Lily Tomlin, and Anjelica Huston).

This film is an anguished cry for humanity and a clear, angry denunciation of Reagan era policies that discriminated against the homosexual community. With many excellent reviews, Band won a 1994 Humanitas Award for its passionate script, as well as an Emmy for Best Dramatic Movie or Miniseries. It also won the cable programming Ace Award that year for Best Screenplay in its category.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Television includes numerous script contributions to episodes for Playwrights '56, Philco Playhouse, Studio One, Omnibus, General Electric Theater, Kraft Television Theater, and others; and And the Band Played On (1993, telefilm, producer and script).

Plays include A Hole in the Head and Jennie.

Nonfiction books include Baba.

Academy Award honors include an Oscar nomination for Best Original Story and Screenplay for Love with the Proper Stranger; and an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay for Goodbye, Columbus.

Writers Guild honors include nominations for Best Script for Wild is the Wind, A Hole in the Head, and Love with the Proper Stranger. Goodbye, Columbus was named Best Written Comedy Adapted from Another Medium.

Can you tell me a little bit about your background and boyhood?

Let's skip the Holden Caulfield-David Copperfield crap. I really hate that. I hate to read it. I hate to talk about it. My background, my history, where I was born, how I started, etcetera. Let's just concentrate on movies and movie experiences.

You won't tell me anything about where you where born, or how you were raised?

I'd rather not. It's boring. Who cares?

How about, where did you begin as a writer?

I wrote my first piece at the age of ten. In school we were asked to write an essay about something. I wrote my essay, and the next day I got a zero because the teacher insisted I had copied from the encyclopedia. I was stunned, horrified, because I hadn't copied from the encyclopedia; I didn't have an encyclopedia. Later, [while I was] stewing on this, several things occurred to me: One was, if she thought the essay was stolen from an encyclopedia, it must have been pretty good. Also, it was like a light bulb turning on [in my head]: I had never realized that writing was a profession; I knew you could be a doctor, a lawyer, run a store, be a farmer; but I didn't know that when you went to the library and saw all these books that somebody wrote each one of them and got paid for it. It was a job! I thought, "Holy shit," and immediately sat down and wrote a little story and sent it to either Open Road for Boys or Boys Life, one of those two magazines. They bought it. I thought, "This is it!" and from then on, I've never done anything else or thought of doing anything else.

So you sold your first story at the age of ten. Do you remember what it was about?

It was based on an incident in my life that happened in a little hillbilly town in North Carolina. I don't want to say very much; but we were the only Jewish family in town, and I just didn't fit in. We had just moved there, and I noticed everybody wore overalls. I somehow managed to talk my mother into buying me some overalls, desperately trying to fit in. But I still didn't fit in, because my overalls didn't have patches on them like everybody elses'. That was the basis of the story.

Between the age of ten and your first Broadway play, were you constantly endeavoring to sell your writing?

Yes. At about the age of fifteen, I invented the newspaper syndicate. Of course, it already existed, but it was an invention for me; I was reinventing the wheel. Instead of selling my little human interest stories to one newspaper, as I had been doing, it occurred to me to get a list of every newspaper in North Carolina in those days, and mimeograph my stories and send them to every paper in the state. I didn't know anything about what I was doing. I just wrote at the top: "Usual rates." I'm making up the numbers, because I don't remember; but, say, there were four hundred newspapers and forty used my stories at ten bucks a shot, that would be four hundred dollars a week at a time when this was a monumental sum. So immediately I started making money and got published and never went through that awful period of rejection, struggle, not getting anywhere, that most writers have.

When I was in my early twenties, as I recall, I moved to New York and immediately started writing my first play. I can't remember the precise date. For some reason, which I choose not to acknowledge, I've never adjusted to the concept of time as a system of indelible numbers meticulously recorded by that Great Certified Public Accountant in the sky. Frequently, I'm absolutely certain that something happened to me last week or last year, when in calendar time it could have been ten or fifteen years ago—and the other way around. At any rate, in order to make a living, that's when I started working in live television. Live television was my real training ground.

Why did you move to New York? Did you have family connections?

I'll just say this about my background. I've been on my own literally, since I've been eleven. I never had much schooling—not much high school and only a little college as a special student to learn about writing. After a month of classes at college, though, I thought, "These people are nuts . . . they analyze things to death." I decided to go to New York because that is where writers went.

I hit a lucky streak in New York. I was helped out by a lot of wonderful people. Robert Anderson, who later wrote Tea and Sympathy, was teaching evening classes at the American Theatre wing, and I got into his class. Before I started working in television, I wanted to spend all my time learning how to write plays; so I did nothing to earn any money. My rent was eleven dollars a month for a cold water flat on the lower East Side, which I shared with another beginning writer, and my basic diet was gallons of thick black coffee, which I read Balzac drank, and day-old bread a neighborhood bakery sold for pennies. I enjoyed the fantasy of being a starving young writer, but my body didn't.

One night, in the middle of Bob's class, I got so weak and dizzy I had to leave. I had no idea Bob knew it was because I hadn't eaten for days, until about midnight there was a knock on my door, and there was Bob Anderson, having walked up five flights, with two enormous paper bags of groceries. In the morning, I found an envelope he had stuffed into my mailbox. In the envelope were five hundred-dollar bills. There's no way I can describe the impact

this act of pure kindness had on me, and no way I can repay it, except to pass it on, which I've tried to do ever since.

Around the same time, the Dramatists Guild formed a group called the New Dramatists, and they selected thirty promising young writers to be part of this group. I was one of them. Among the others were Robert Anderson, Paddy Chayefsky, Bill Inge, Stephen Sondheim—an astonishing group.

Every week we would meet in the conference room at the Dramatists Guild. We'd meet with the great playwrights of the period—[S. N.] Behrman, Sherwood Anderson, Oscar Hammerstein, Maxwell Anderson, [Howard] Lindsay and [Russel] Crouse—and discuss craft. I'll always remember Howard Lindsay talking about comedy. He said, "When you take the play out of town, take your biggest laugh, wherever it may happen to come for the audience, and put it at the end of act 2. Just rearrange the play and put it at the end of act 2. It sounds crazy, but just try it; we've been doing it for thirty years." That kind of thing. We'd sit around a table and ask them questions about "planting" here and "paying off" there, especially about comedy—how the word that gets the laugh has to be the last word in the sentence—really technical craft stuff.

Why did you decide to make the leap from writing fiction to writing for the theater?

I made a lot of idiotic decisions that I regret bitterly now. Originally, I wanted to be a novelist. But it was a matter of expedience. I thought, "A novel is 400 to 500 pages, and a play is 100 to 120 pages." I chose the shorter form to start with. That was the deciding factor, although of course I liked drama and I liked theater.

Did you have any experience or particular love for the theater?

I second-acted a lot—meaning, waiting outside, and when people go back in after the second act, you walk in with them and find a seat or stand up. After I got to New York, I saw everything I could.

How did you go from theater to being involved with live television?

Bob Anderson's wife at that time, Phyllis, was working at the Theatre Guild, which at that time was probably the most prestigious theatrical producing organization in the world. When I wrote my first play in Bob's class, because of Phyllis the Theatre Guild optioned it, with plans to produce it the following year. In order to keep me alive during that time, she got me into television working on Omnibus, GE Theater —all the shows now known as the Golden Age of Television. I wrote one every week.

A kinescope of one of mine was shown recently at a festival here—James Dean and Natalie Wood in a half-hour drama on GE Theater. Another was shown on PBS—Paul Newman in "Bang the Drum Slowly." When you see one of them now, they don't really hold up. But given the limitations of what we had to do—knowing the character had to be laughing in this scene and, within two seconds for the very next scene, run all the way across the studio and be sitting somewhere else and sobbing—they are amazing.

Live television was the most valuable training a writer could have. We could do anything we wanted. It was an opportunity to learn [by doing] and to see your work performed immediately. You had to learn the technique of writing to allow time for one of four cameras to get from one set to another, to frame the shot and focus, as well as laying out the structure so that the actors, who frequently had to change costumes while running, had enough time to make the transitions. It was like logistics, a military game. Sometimes it was chaos. In almost every show, a camera would conk out, and at the last minute, you'd be feverishly rewriting to rearrange scenes. There wasn't any time for second-guessing. Time pressure gave us the freedom to be bold.

Those early days were marvelous in many ways. Something I miss terribly now is that we were a community of writers then. We were close, we would call each other for help. We were a family. I remember Paddy Chayevsky, who was my closest friend—especially during that period—calling one day and saying, "Boy, I'm in real trouble here. I've got to give [the producer] Fred Coe a script on Thursday, and I don't know what the hell to write . . . " I went over to his place, and we talked about it. He had an idea to do something about some little, short fat guy who can't get a date. We stayed up all night until eight or nine in the morning, working the whole thing out, talking it through. Paddy wanted Marty Ritt to play the part, so in talking the story through, we'd refer to the character as Marty. Paddy wrote it. All I did was act as a sounding board. That sort of thing happened all the time. When I needed help, I would call him or Bob Anderson or whomever. And, of course, we'd go out of town to see each other's plays and make suggestions.

You continued to work in the theater at the same time that you were writing for live television?

Yes. I was also a member of the Actors Studio—the very, very first group—before they moved to the church where they are now, with [Marlon] Brando and Monty Clift. Phyllis Anderson was a close friend of Molly Kazan, who was married to Gadge [Elia] Kazan at the time. She said to Gadge, "Why don't you let him [Schulman] sit in? It will be helpful . . . " I wrote scenes and directed them, and again it was a wonderful experience. I had no idea of becoming an actor, but so that I could understand the process of acting and therefore write better plays, they got me little jobs as an actor. I had two lines in Come Back, Little Sheba on Broadway. And I remember Rod Steiger and I were among the extras in Arthur Miller's Enemy of the People.

What did studying the Method teach you that was helpful to you as a writer?

My first reaction would be to say it set me back about ten years. But that's facetious, because I did learn a lot about subtext. I learned that very often the best writing is the line that says the opposite of what the person means. Obviously, I learned a lot by osmosis, by doing it, by learning what plays and what doesn't play. It was a really extraordinary piece of good luck, being in the right place at the right time. It was a wonderful time to experiment. Brando,

Clift, Paul Newman, so many others were in the class, and they were in my pieces. They were all available, eager to do any scene you had. We were all working together. Of course, many of them turned out to be the best actors of our generation, but at that time, nobody knew if they'd ever get a job.

Directing actors for the first time, what did that teach you as a beginning writer?

It taught me that actors are dangerous creatures—to beware. (Laughs. ) Again, I'm being facetious. Actors want to make a contribution, and they should. You cast them because you want a certain quality. But just as I said the best writing is sometimes where you don't say what the person is really feeling or thinking, what actors want to do can be very frustrating to a young playwright. If I wanted the line to be sad, they wanted to play it laughing. As an older writer, I say, "Yes—give me more of that!" I learned a lot from them, working with those incredible people.

Did [Elia] Kazan or Lee Strasberg have much to say about writing?

Absolutely. As I recall, they basically indicated that writing and acting are the same thing. I've later discovered that is true: When I sit down to write, I'm improvising. It's coming, not from my head, but from somewhere else. I learned from that period, I guess, just to let it happen; and then to come in afterwards as an editor—distinct from my job as the writer—and do the cutting and editing.

Clifford Odets taught a playwriting class at the Actors Studio, only for writers. His class was fascinating, especially for me. He was one of my gods. And at that time—I don't know why, [but] probably because of the way I was writing—I was called, or considered to be by a number of people, a young Odets, whatever that means.

His class was different in contrast to those once-a-week groups with the great playwrights. They talked about craft. Odets talked about art. Therefore, I can't remember anything he said. It was basically a waste of time for me, an ego trip for him. He was being Clifford Odets, acting Clifford Odets. I didn't learn anything specific—like where to put your biggest joke—although I probably learned something by osmosis.

Then my play was ready. We were going to try it out that summer in Westport. I insisted that Lee Strasberg direct it. People said, "You're crazy. You mustn't do this. A wonderful teacher he might be, but he's a rotten director." I was very young and very pretentious—I said no. He too was a god to me. The play was a total disaster because between the lines "Hello?" and "How are you?" each actor did five minutes of "sense memory." The title of it at that time was My Fiddle Has Three Strings —I told you it was pretentious. It was a normal-length play that lasted about six hours on opening night. I remember a pivotal moment in my life. In the audience was Noël Coward. At the end of the first act, I sneaked over behind him, wanting to eavesdrop on what he was saying. "Well, actually," he said to his friends, "I think it should have been

called 'My Fiddle Has Two Strings—Oy and Vey.' " (Laughs. ) I thought, "Oh, God, my career is over."

It was a big flop. Meanwhile, I did some rewriting on it. One time I was stuck for a script for Fred Coe, so I took that play and rewrote it into a television play and changed the title from pretentious to even more pretentious: "The Heart's a Forgotten Hotel." Arthur Penn directed it with Sylvia Sidney and Eddie O'Brien. It was a beautiful production, the best it ever was. The next day, I got a call from Gar Kanin, who said, "Would you be interested in turning that show into a play?" I said, "I have already got it as a play." Of course, I had changed it, so it wasn't a play anymore; but I stayed up all night and rewrote it back into a play and gave it to him. Gar didn't like the new title, and by that time, neither did I. Gar came up with A Hole in the Head, because we were desperate for a new title. It was a Yiddish expression: You need this like a hole in the head. I had no idea how it applied to the play and still don't.

Then came one of the critical moments that shaped my life, and which I've regretted—one of the big mistakes, I think, in a way, and then again, it isn't. Gar Kanin cast Paul Douglas, David Burns, and other old comics, and we took the play out of town. The audiences went into hysterics at the funny stuff and hated the serious stuff. When the piece was on television, it was very, very simple, not a comedy at all. It ended very unhappily. It was a tiny slice of life, done brilliantly on television. Now we had this gigantic, revolving set, which didn't make any sense for this small play, and the play was all out of whack from where I [had] started.

I was confronted with the problem by Kanin. He was very gentle and wonderful; he would rather have had a flop than disturb a young playwright's life. I realized I had the power to make him do it exactly the way I wanted it to be done and have a flop, and who would care? It would last three days and close on Saturday. Or I knew easily how to fix it and make it into a hit. Just take out the serious stuff, put in more jokes, and give it a happy ending. And that is what I did. Since then, I've felt that is the moment when I sold out. That is the moment when I really sold out.

I've heard writers, especially screenwriters in interviews, asked from time to time: "If you had your life to live over again, would you change anything?" And they say, "No regrets." I have nothing but regrets. Everything I've done, every decision I've made in my life, pretty much has been a disaster.

That decision echoed down the line for you?

That's it. From then on, it was not that I was writing down to anybody, but I took the road of "I'll make the movie and follow the conventions," the professional, pragmatic way, rather than the way of the artist.

Was it a case of being corrupted by money?

No, money had nothing to do with it. Later, it got to be money. That decision was not based on money. That was based on being a pragmatic professional, which I had learned in those years of live television. Doing what had to

be done at that moment to make it work. We were on the road. I was trained by then that as a professional, my job was to take what I've got and make a hit out of it. You don't sit back when you've got a flop and say, "I'm a wounded artist," and write a letter to the Times. Who cares?

Did your decision have anything to do with a possible latent insecurity that you weren't an artist, couldn't be one, didn't have the stuff?

No. None of that occurred to me until years later. I've always regretted not doing what Doc Simon [does]—I'm sorry, Neil Simon; he's not Doc Simon any longer, just like Gadge is no longer Gadge Kazan; he hates that name after everybody's called him that for twenty years. Neil's written a play every year, and he's written movies. I could have done that. Unfortunately, I chose other priorities.

Later, money came into it, because money creeps up on you. Your lifestyle gets more expensive. After I started writing movies, we—I was married at the time—moved from a basement apartment, literally subground in Greenwich Village, and bought Joan Crawford's apartment on Sutton Place. It was that leap. Plus, there were two kids and private school . . . now you better earn money. And then suddenly you wake up, and you can't pay your taxes; so you've got to do another movie.

Did producer Hal Wallis see your play? Is that how you ended up in Hollywood?

Hal Wallis hadn't seen the play when he first contacted me, because it hadn't opened yet. It was cast and announced, but we hadn't gone into rehearsal. I don't recall the precise chronology. But my agent knew Hal and told him about me. Hal had already done The Rose Tattoo [1955] with Anna Magnani, and had the option to do another picture with her. She wanted to remake an Italian movie called Furia [1948] because she was in love with [Robert] Rossellini at one time and wanted to be in this particular movie which he was planning to do. When he pushed her aside and fell in love with somebody else—not Ingrid Bergman—she vowed that some day she'd make the movie without him as a kind of vengeance.

It was a dumb story, basically the same story the musical The Most Happy Fella is taken from: the mail-order wife. But she wanted to do it, and what she wanted, she got. He asked my agent—Abe Lastfogel of William Morris—if I'd be interested. They screened Furia for me and asked if I could figure out any way to do this piece of shit. At first it seemed hopeless; but I figured out a story line and went to Hollywood to meet with Hal, and after listening to me, he said, "Great, go to work."[*]

* The official credits for Wild Is the Wind stipulate that the film is based on Furia, a novel by Vittorio Nino Novarse.

That was the only film school I had, and it's all you need. I have since heard this story attributed to many different people, who supposedly said it to other people, but Hal said it to me. He said, "Don't worry about writing for the movies. This is all you need to know: When Sam Behrman came to write a script for me, in the first scene we had to show the husband was losing interest in his wife. Sam wrote a ten-page scene that was brilliant—witty, insightful, marvelous. I said, 'Sam, this is fantastic—as a play. ' I tore it up and said, 'Here's how we do it in the movies. The man and his wife get into an elevator. He's wearing a hat. He doesn't take it off. The elevator goes down one flight. The doors open; in steps a pretty woman. He takes off his hat. That's all you need to know.' " I realized what he was saying. It's a different language. It is like translating something from French into English, from words into pictures. That really is all you need to know.

Did you have any background as a movie fan?

Of course. I lived in the movies. And I had all this experience of working in television, which was similar to movies, although in some ways, it was more like plays, because we didn't have the luxury of even shooting an outdoor scene. It was always on a single set.

Did you have any attitude towards Hollywood?

No, I never looked down my nose. I liked the process of movies. I thought it was exciting. I was fortunate. My first movie was with George Cukor; my second was with Frank Capra. You hear so much about Hollywood's bad treatment of writers. I guess I slipped in the door in the period between the Golden Age and the Writer as the Hollywood Nigger. With Cukor and Capra, we worked out what we wanted to do, and they never changed a word without asking me. I went to all the sneak previews, was invited into the cutting room, made suggestions all the way through, and was listened to as an equal, a peer. Here I was, a young kid with no experience, and I was listened to; not that they did everything I said, but at least they listened and talked and worked things out.

Were Cukor and Wallis helpful in terms of the script?

Extremely. Very helpful. Unlike now—it astonishes me that it's been allowed to happen—people who have never seen a piece of film or have never written anything, not even a letter, suddenly they are telling you how to rewrite your script. They are in the editing room, telling the editor how to edit the film. It's nuts. In those days, everybody knew what they were doing, and there was mutual respect. You respect my job, I respect your job; and we work together. It was really working together.

Actually, Wild is the Wind started out as a project for John Sturges. I worked with Sturges and Wallis on an early draft. But Sturges considered himself an action director, and at the point that it was clear the project was turning into a love story with real people, he either quit or moved on. Cukor was obviously the choice to direct Magnani, the great actress of the day.

Cukor and I met almost every day at Cukor's house. We would begin at some civilized hour, say ten or eleven, break for lunch, and work until three or four. There was never any pressure, never any hysteria, just exploration. We talked and talked and talked. Being a young filmmaker, I was very conscious of visual metaphors and symbols, and he was very receptive. When I got too ambitious, he would gently lead me away from my excess. He was very clear about what he wanted. He and Wallis really knew their craft. "If we are going to do this here, we had better plant it there." "This scene is too long." "You don't need this character; let's combine it with this one." It was all very technical craft stuff.

You're going to have problems if you start making a movie and you don't have a finished script. For some reason, I decided to set this movie on a sheep farm in Nevada. An important scene took place when the lambs were being born; but when the lambs were actually being born, the script wasn't finished. We had to go on location and start shooting, because the lambs weren't going to be born again until next year. (Laughs. ) The birthing of the lambs was going to take place somewhere in the middle of the story—but we didn't quite know where. So I was literally on location, writing the next day's scenes, having no idea what came next [in the script]—nor did anybody else. I took a lot of ideas from the location. I spent an enormous amount of time with Magnani and incorporated little mannerisms of hers into the script. It was a very exciting, stimulating experience.

In his autobiography, Hal Wallis talks a lot about the harsh location and about Anna Magnani proving spoiled and difficult.

She was a pain in the ass. She held up the filming. She asked for a Jeep to be sent to her home in Italy, or she wasn't going to work the next day. She got in bed and played sick, and they had to call in a local doctor from Carson City to the motel where we were staying. He said, "There ain't nothing wrong with this woman. If you want a dark-haired 'eye-talian' woman, we've got hundreds around here. Why don't you get another one?" (Laughs. ) But Wallis gave her the Jeep. I'll always remember she kept yelling, "With a shovel! Don't forget the shovel!" A Jeep with a shovel? Why, I don't know.

In his book [Starmaker: The Autobiography of Hal B. Wallis, by Hal Wallis and Charles Higham (New York:) Macmillan 1980] Wallis said there was competition between Magnani, Anthony Quinn, and Tony Franciosa for close-ups.

Yeah, that I remember, everyone bitching and complaining about their close-ups. And Cukor had to explain things to Franciosa—I think this was his first picture. Cukor shot absolutely by the book: the master shot, medium shot, over the shoulder, a two-shot from this angle, a two-shot from that angle, his close-up, her close-up. It was one, two, three, four, five. I remember him explaining to Tony Franciosa, "My dear boy, wait—we're only at one now. When we get to five, you'll get your close-up . . . we'll do everyone's close-ups in turn." That was the end of that.

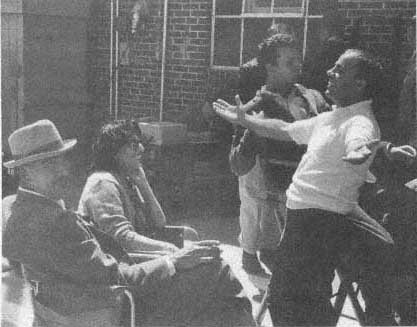

Arnold Schulman (gesturing) on the set of George Cukor's film Wild Is the Wind , with

(from left) Anthony Quinn, Anna Magnani, and Anthony Franciosa.

(Photo by Bill Avery.)

Some of the scenes were difficult. We had one scene that Arthur Miller used many, many years later in The Misfits [1961], where they were capturing wild horses by tossing rubber tires around them. In this case, the scene had to do metaphorically with this wild creature, Anna Magnani. The horse was her. It wasn't an impossible scene by today's standards where you can blow up New York [on the screen], but it was difficult.

Some of those outdoor scenes seem beyond Cukor, especially the horse-capturing scene, which is not filmed as well as it should be.

I think it was second unit.

The situation must not have been very congenial for him—the shooting conditions, the script in progress, Magnani, and the other cast troubles.

It was awful. I remember it very well: the weather, bad food, the motel, Cukor arriving with his own silk pillow to sleep with on location. There was also a lot of—I won't go into the names—midnight crawling from bunk to bunk of the cast. But Cukor had infinite patience. Though in most ways he didn't impose his personality on the film, what he did bring to it was his sensitivity about people and the human condition.

Were you gratified by the result?

There were sections of the film that became really stupid in order to conform to Magnani's revenge: getting even with Rossellini. But there were moments in it that I liked, and I liked the fact that this was the first picture that I can recall where the woman committed adultery and wasn't killed or punished at the end. In this one, the husband begged her for forgiveness, which was a revolutionary way of looking at things. That I liked. That was the honest way to do it. I felt the other way was a cliche, and Cukor agreed with me.

Can you compare Cukor with Capra for me in terms of craft, expertise with the script, your experiences of working with them?

They were totally different people, but their working technique was exactly the same. Capra shot exactly the same way as Cukor. That is the way the studios had taught them to shoot. They didn't want to get caught without coverage.

I think of Capra as being more of a frustrated writer than Cukor. Capra shows up in several biographies and sources as grabbing credit as a screenwriter and once in a while being forced into arbitration with the Guild.

In Capra's case, where we had more leisure, we worked on the script line by line and word by word. He and I never had any problem. In fact, he has a little section in his book, The Name Above the Title [New York: Macmillan, 1971], about when I first cameout to do the screenplay [of A Hole in the Head], and he brought up what I thought was a ludicrous idea. I was young, cocky, and I told him it was ludicrous. He laughed and said, "You know, I'm the director. I can do any damn thing I want to." I said, "No, you can't. I'll give you your money back," which has been my attitude throughout my entire career. I have given money back every time someone doesn't do what I want to do. It has screwed my career; my agent thinks I'm crazy; and it hasn't done my bank account any good either. Anyway, Frank and I got along very, very well after that. That established a kind of equality, and when I explained why we couldn't do what he wanted to do—which made sense to him—he understood that I knew what I was talking about.

The preproduction of that film went on for months. It was the most glorious time of my life. Here I was, this young kid, and Frank and I'd have lunch every day at Romanoffs. All the people in the cast came in to see him, one at a time. I got to meet Edward G. Robinson, spend a weekend with Sinatra at his house. Everyone worshipped Capra, and I did too. It was just a beautiful experience.

Again, I was brought into all the decisions, even the technical decisions. In those days, unlike now, Capra would take the sneak previews to many different places. I was always there with him. He had tape recorders set up all over the theater, so he could find out where the laughs were and how long they were, and if they were too long and overcutting another line, we'd leave room for them.

Did you have any sense of him winding down in his career?

I loved the man. I really loved him. He was a sweet, wonderful man. I saw him by accident a few years before his death on the street in San Francisco. We hugged each other and started to cry. We went in somewhere and had coffee and started to reminisce. He still remembered the time and everything that had happened.

But he told me, while we were still in preproduction, that he was thinking of quitting. Because he got on the set one day and could not think of a piece of business in how to stage a scene. He found himself in desperation going back to a piece of business that he had used in a previous film. He decided he had to get out. He felt he couldn't do the job anymore.

How did you feel about the film when it was finished?

The first time I saw the film put together I was mortified. It was so goddamn sentimental that it was nauseating to me. I was embarrassed. I'm still embarrassed. What a metamorphosis! It had started as the Lee Strasberg version—all art—suffering and pain and heat. It turned out to be Frank Capra's A Hole in the Head. Joke, joke, joke, yuk, yuk, yuk. A hell of a metamorphosis. (Laughs. )

Even though you were partly to blame? After all, you had been integrally involved in developing the screenplay with Capra.

Yes. But I didn't know how truly sentimental it was until I saw it all put together. When I saw dailies, I might cringe at certain takes; but I thought, "Oh, I'm sure that will be cut out." But Frank didn't cut things out. He just piled it on. Even today, it's running constantly on television, and people will come up to me and tell me how they loved it and cried during— it and I'm thinking, "How is that possible? Are they just being nice? Why bring it up at all?"

Did Capra have the same reaction as you?

No. He thought it was marvelous. In fact, he came to me to write his next movie, about Apple Annie—Pocketful of Miracles[*] I just said no, I couldn't do it. Of course, I couldn't tell him the real reason. I just said it wasn't my kind of thing.

You weren't honest with him?

No.

How about working with Anthony Mann on Cimarron? Was Mann in a class with Cukor and Capra?

No. Not at all. He was a nice, sweet man, but I got the feeling he was sort of burned out. The whole film was a disaster. The studio was a mess. The head of the studio was in danger of being fired. There was a lot of tension; the picture was costing too much; and we couldn't get the script right. It was a badly

* Hal Kanter and Harry Tugend ended up adapting the script, which was a remake of Capra's 1933 film Lady for a Day, based on a Robert Riskin screenplay.

written script. I take my share of the credit. I didn't mean it to be bad, but it was one of those things you get sucked up into.

Was Anthony Mann literate at all?

Oh, he was a nice man. He wasn't literate the way, say, Garson Kanin is literate, but neither was Capra. Cukor was literate.

Was he helpful with script problems?

No. I don't remember talking to him at all about the script.

Why did you even do the film?

It sounded fascinating. I always wanted to do a western, and Anthony Mann was a big-scale western director.

Was Edna Ferber around at all for script discussions?

No, and I destroyed her book [Cimarron (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubledy, 1930)]. I regret it. I hope she'll one day forgive me in another life. I didn't mean to. We were just trying to solve the problems of the picture. But once we were given the cast, Glenn Ford and Maria Schell—what the hell was she doing in an Edna Ferber story?—what could we do? We were dead from that moment on.

You had just had some rather dubious writing experiences in Hollywood, yet you ultimately turned your back on Broadway and continued to write motion pictures. Why?

Believe me, I regret that decision now. I regret it bitterly. The movies may not have been great, but the experiences, especially with Cukor and Capra, were wonderful. When I went back to New York and did a Broadway musical [Jennie ] with Mary Martin, the experience was a nightmare. The play was hideous. There was tension all the time, and nobody was talking to each other. So I said, "Screw this. I don't need this." I wanted to go back to Hollywood, where it was fun. Broadway was traditionally where the playwright was king, but in this situation, Hollywood treated me better.

It was in Hollywood that, at least in the beginning, I was treated like a playwright. So I came back here and had marvelous experiences throughout the sixties, especially with Love with the Proper Stranger and Goodbye, Columbus.

Your experience was the opposite of most writers—you felt you got more respect from Hollywood than Broadway.

Exactly. Until things changed. Gradually, in the early seventies, there was a change. That's when the writer became the Hollywood nigger. When you look back, that is when the movies started being taken over by conglomerates. Then you got businessmen who didn't know what they were talking about. Up until that time, everybody [in Hollywood] knew the movie business—every inch of it. Everyone knew everything they had to know; and after that, nobody knew anything they had to know but acted like they did, and they demanded you do what you knew was wrong.

Now the writer doesn't get any respect. You are treated like a hired hand, worse, like dirt. It is like: The toilet is clogged up. Unclog it and please get out as fast as you can and try not to track up the rug.

I know from reading David Brown's autobiography. Let Me Entertain You, that you had at least one not-marvelous experience in Hollywood in the sixties, working with Cukor again, this time on the last, never-completed Marilyn Monroe picture. Something's Got to Give.

I haven't read David's book, but I've been told he said I wore a kimono and sat on the floor when I wrote. Clearly, I was crazy, so he fired me. I still wear a kimono and sit on the floor when I write, and lots of people think I'm crazy— maybe I am—but David and I recall the situation differently.

Actually, I quit. Cukor wanted me because we had such a good experience on the Magnani picture, but when I found out what they were doing to Marilyn, I quit. They were setting her up. A guy from the advertising business named Peter Levathes had come in as head of the studio, having taken over from [Spyros] Skouras, who was kicked out, as I recall, because Cleopatra [1963] went so much over budget. Levathes had to prove himself a hero. He had to prove he wouldn't take any shit from any star. He wanted to humiliate Marilyn into quitting and then sue her, I was told.

You were Marilyn's friend?

From way back. I met her when she first left Hollywood and came to join the Actors Studio. I got a call one night from Lee Strasberg, and he said, "I've got two tickets to a poetry reading at the Y. I can't go. Will you take the person I'm supposed to go with?" I said, "Sure." I had no idea it was Marilyn until she opened the door. This was at the peak of her fame. I didn't have a car or anything, so we had to catch a cab. We got mobbed. We finally got to the Y. I'm thinking, "Why does she want to go to theY? Why didn't Lee tell me who I was going with?" And, of course, the program couldn't go on, because everybody left their seats to catch a glimpse of her. We escaped through a side door and ran up the street with a mob chasing us, and finally wound up on 125th Street in a dinky Chinese restaurant I knew about. That's how I met her, and we became good friends.

What was her condition at the time when you were working on the script? Was she deteriorating, as everybody has written?

I didn't see any of that. When I was with her, she was bright, warm and loving, and in good shape.

She wasn't demanding?

Not at all.

She was on time for everything?

She didn't have to be on time. This wasn't even preproduction. I hadn't written a word. But her agent would call and request things—I remember one thing in particular—and Fox would deliberately say no, doing everything to make her quit. She wanted her regular hairdresser, I remember. No—she couldn't have her regular hairdresser. Whatever she wanted, the rule was, she

couldn't have it. Gradually, it became clearer and clearer what was going on—and then I overheard conversations about it between the executives.

As soon as I realized it, I went ape. I think I grabbed David Brown, who is about two feet taller than I am, and shook him against the wall; if not, I wanted to, which is probably closer to the truth. I called Marilyn and told her. She understood what was happening, but there was nothing she could do about it.

You think they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams—driving her to her death?

It's not that cut and dried. But they certainly didn't contribute to her will to live.

Cukor was party to this?

He knew about it.

That's shocking.

The whole thing was shocking to me. She asked me to come back and write the picture and be on her side. I told her I was on her side, and that is why I got out of it. I told her she had to get out of it. "If I go back," I told her, "I'm powerless." I have terrible guilt about that experience, still. Terrible guilt. The lingering feeling, however irrational, that if I had gone back, I might have made a difference, and she might still be alive today.

How did Love with the Proper Stranger evolve?

It was difficult to sell the idea: In order to escape her family, a young virgin has sex with a stranger and gets pregnant. She looks up the guy afterwards, and during the course of trying to arrange an abortion, they fall in love. People said, "Are you crazy? What kind of love story is that?"

I pitched it around, but nobody would do it. So I said, "Screw everybody. I'm going to write it anyway." At that time, my normal procedure was to do a pitch, not write anything. To me, the idea of a treatment or an outline is ludicrous. You can't write [in an outline], "Here is where there will be a hilarious scene . . . " You have to write a hilarious scene. What really drives me nuts is this whole new trend where everything is a cross between this and that. Everything is pitched as a cross between Stars Wars and Wuthering Heights. That's why I don't go to the movies at all. Occasionally, I'll watch a few minutes of a movie on cable. That's about all I can take. If enough people I respect tell me there is a picture I'll like, I'll go. Otherwise, I don't want most of today's films in my head, because I'll start thinking, "Maybe I should do a cross between this and that," and everything will become derivative.

Anyway, [my agent] Abe Lastfogel believed in the idea. He got Natalie Wood first and sold the script to Paramount. He wanted Warren Beatty because Natalie and Warren were living together, but Warren wouldn't do it. Then he got [Alan J.] Pakula and [Robert] Mulligan, who had just won the Oscar for To Kill a Mockingbird. Pakula and Mulligan plus Natalie was fine, so the studio said, "For the other part, let's take a chance on this new kid, [Steve] McQueen."

Why did you think the film turned out so well?

We did it like a play. I was involved like a playwright all the way through. There was mutual respect. Rehearsals on the set, everything. In fact, some of the best scenes in Love with the Proper Stranger and Goodbye, Columbus were written in rehearsal, just as you would in a play. I would see something and say, "Gee, we need another scene there." I'd write the scene in a corner, give it to the director, and we'd put it in.

McQueen put up with rehearsals?

It may have been his first big picture—I'm not sure—but he certainly wasn't a big star. I didn't pay much attention to him. As I remember, he asked me during the course of filming if I might want to set up a company with him and make other movies. I remember thinking, "Why would I want to set up a company with him? " (Laughs. ) He was very nice and cooperative.

Tell me about The Night They Raided Minsky's. What happened there?

I don't know. I got replaced—to my surprise. When I left [after finishing the script], they gave me a party, and I thought the script was all settled. The next thing I knew, another writer was on the film. He added the character of a gangster, I think. I don't know why. I later learned—from a book by the editor Ralph Rosenblum[*]—that they had trouble assembling the film, and that the editor put it together by intersplicing footage from old, silent films. So large sections are things that I wrote, but I had nothing to do with what made the film special—the addition of archival footage—and I wasn't there for the shooting.

Was it just a job for hire? Was it a personality conflict between you and the director, William Friedkin?

I never met Friedkin. I still have never met him.

How did you get involved in Goodbye, Columbus?

Stanley Jaffe and I knew each other casually. Stanley was only twenty-eight years old at the time and had never produced a film. By now I was really flying high, with one Academy [Award] nomination. Stanley came to me and said, "I don't have any money. Will you do this picture for scale, and we'll work out some percentage deal?" I read it and said, "Sure." It was altogether a perfectly wonderful experience from beginning to end.

Why?

Again, because we worked together, like a play—me and [the director] Larry Peerce and the cast and Stanley. In particular, I remember what I think was one of the most affecting scenes in the film—the scene at the wedding where she was feeling guilty about having slept with a guy at her house, and she and her father go off and have a conversation in the corner, and he tells her he loves her and will buy her a mouton coat. I wrote that during rehearsal. I

* Ralph Rosenblum and Robert Karen, When the Shooting Stops . . . the Cutting Begins (New York: Viking, 1979).

"A nice, little story": Richard Benjamin and Ali MacGraw in Goodbye, Columbus.

wrote a lot during rehearsal; we did some rewriting after filming, in fact in postproduction and then reshot some stuff.

Did the novelist Philip Roth have anything to do with the script?

Philip took me to Newark and showed me around—the house where this happened and the tennis court where that happened. He filled me in on stuff that wasn't in the story as he wrote it. That was the sum of his involvement.

As I listen to myself now, I realize that all the films which I was involved with intimately from beginning to end were the satisfying ones. By coincidence, and I say this not to be self-serving, those were the good ones, and the rest of them were not as good. Clearly, that suggests that it should be a law, like marriages: Before you get married, you should live together for a year. Before you do a movie together, all the principals should work together for a few months to see if you are going to get along, whether you respect each other.

Did you have any special identification or empathy with the material? Does that have anything to do with why you might stick with a project longer, or why it might work out better in the long run?

No. As a matter of fact, I thought Goodbye, Columbus was just a nice, little story. When I first saw the rough cut of the movie, I thought it didn't work,

and that it was merely okay. I remember thinking, "I'm glad it's not funny. It's almost better that it's not funny." Of course, it turned out to be a huge comedy. (Laughs. ) I think I had, like, 7½ percent of the gross, which turned out to be a tremendous amount of money at the time. That's when [Charles] Bluhdorn from Gulf and Western took over Paramount, and everything was in chaos at the studio. So, as a result of that picture, his first picture at age twenty-eight, Stanley Jaffe was made president of Paramount Pictures. Astonishing!

Do you have any particular interest in abortion? To Find a Man is also about abortion—the second film, after Love with the Proper Stranger in your filmography to touch on that subject.

I got seduced into To Find a Man. Ray Stark is the most seductive, irresistible louse in the world. I used to love him, but he is a louse. I loved him, even though he screwed me outrageously time after time. Now I despise him. There were all kinds of carrots that he dangled in front of me to get me to do that script—including directing—things which are too complicated to go into. I won't even go into the disaster aspects of that film, but we parted with me saying, "Go fuck yourself, you prick! I never want to see you again." Afterwards, I was off in India, and I spot a guy running towards me, way off in the distance. He runs and runs and finally reaches me with a cablegram, and it is from Ray: "Are you interested in writing a sequel?" (Laughs. ) I wrote him a long, long cable, saying, "Go fuck yourself!"

Cut to years later. I had never met Max Shulman. We had lived near each other in Westport, where I would always get his laundry, [and] he got my mail. Then we lived near each other out here—I would get his wine, he would get my groceries. But I had never met him. On a picket line during the big writers' strike, I noticed him, and went over and introduced myself and said, "Even if you have to lie, just say yes to this. Does anyone ever congratulate you for something I did?"—because I was always getting congratulations for something that he did. Then he told me this funny story: "When Ray Stark couldn't get you for the sequel [to To Find a Man ], he called me . . . " The sequel never got made, but he did get paid for working on it. So one Shulman was as good as another to Ray Stark! (Laughs. )

Tell me about Funny Lady.

Ray talked me into it. I had sworn never to work with him again. Suddenly, I was at the Beverly Hills Hotel, working on Funny Lady. But I blew it. I ran out of steam or something. Jay Presson Allen came in and deserves most of the credit. She rewrote almost all of it, and the funny part about it is that the Guild kept giving me more and more credit. I wasn't doing anything to claim credit; it was an automatic arbitration. We had to write a letter saying what we had done on the script. After the first credits were awarded and I was given credit. Ray was adamant about giving all the credit to Jay Presson Allen and had his lawyer appeal the arbitration; then the Guild came back and gave me additional credit. It became a joke. I sent Ray a telegram: "Appeal one more

time, and I'll get a 'written-directed-and-produced-by' credit." I'm embarrassed really, because most of it was her screenplay.

You had long stretches of not writing in the 1970s.

I just stopped. I started traveling and went into my own private world. I've always had this unusual pattern: When I'm here working on a script—I know some writers work two or four hours a day, whatever—I work all the time. That's all I do. I don't go out of the house. I don't do anything else. I work day and night, take a nap, and go back to work, until it's done—whether it's three to four months. The minute it's done, I lock the house up and go to another country. Preferably a primitive country—the Amazon, living with the cannibals in New Guinea, lots of time in India. I used to go every year for a month to a Zen monastery in Japan. I don't know why, whether I was searching or what. I only know the superficial reasons: The so-called primitive people are very exciting. It is literal time travel. I can step off a jet and a day or two later be in the Stone Age, literally—with people who use stone axes and spears. They are much more civilized than the people in the movie industry, who use loopholes and lies instead of spears.

Whenever I finished the writing, I used to go on one of these adventures. But the other part of the pattern is that right after one of these adventures, I would head straight to Claridge's in London. I would go from the Stone Age to silk pajamas. I would recoup at Claridge's and then come back and start over again.

Except I realize I did take almost the entire decade of the seventies off. I got disgusted with the way things were going, what was happening, the kinds of movies that were being done, and the way writers were being treated. So I took a trip that led to another trip and another, and suddenly I realized it was the eighties. I came back twice to get enough money to continue traveling.

One was Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood?

The story of how I got involved with that is too long and stupid to go into. To tell the truth would sound self-serving—the perpetual complaint of writers who get publicly flogged for what the owner of the plantation did. All we're supposed to say is: "Feets don't fail me now!"

At any rate, not only did David Picker, the producer, have every word of the script rewritten, but he hired Michael Winner, the director of all the Charles Bronson Death Wish pictures, to "realize" the film, as the post— Cahiers du Cinéma directors like to put it. It was written by me as a satire, written by God-knows-who as a slapstick farce, and directed with all the charm and wit of a chain-saw massacre. I had nothing to do with the final picture, and on that one, I was not only listed as cowriter but also as executive producer, and I couldn't get my name off! (Laughs. )

Both Won Ton Ton and Players were totally rewritten from scratch. I had nothing to do with either of them. Nothing. Not a word. They haunt me to this day. Just seeing wonton on a menu in a Chinese restaurant makes me want to throw up.

The other one was Players.

Finally, after all the years, it was a great triumph to me; I got in my contract all of the Dramatist Guild guarantees: I had approval of the director, not a word [of the script] could be changed without my consent, and so forth. Immediately after I finished the screenplay, [the producer] Bob Evans sent me on a wild goose chase to Rome to cast a part he had already cast—I found out months later—with Max Schell. When I got back, I found out that six or seven writers were working on different versions of the script, all at the same time with none of them knowing about the other. Then the company went to Mexico [for the filming], and I couldn't get Evans to show me the dailies. I said, "Bob, you have no right to do this. Look at your contract." He said, "Sue me!" That was the end of that. I had these things in writing, and they meant nothing!

So you sued him?

I did sue him. But I couldn't take my name off the screen. You can't take your name off the screen if you're paid a certain amount of money, unless the studio agrees beforehand—and they're not going to agree, because if word gets out the writer took his name off, the picture gets a bad name.

Can't you take a pseudonym?

You can—if you have that clause in your contract in the first place. That's one thing I didn't have in my contract. It never occurred to me that I would be double-crossed.

Is any of Players your script?

Not at all. Not a word. But I got the credit, the money, and even the credit of executive producer once again, and from the outside, it looks as though I was totally in charge. I ran a full-page ad in Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter when Players came out. On the left side of the ad, I quoted all the major critics, just what they said about the screenplay: "This is the worst script I've ever seen in my life . . . " or "The garbage Arnold Schulman has written . . . " They all mentioned me! The last quote at the bottom of the page was from L.A. Magazine: "Bob Evans is particularly proud of his new picture Players. It involves the two things he loves best in life, Ali MacGraw and tennis, and as a consequence, he rewrote every word of Arnold Schulman's script." Then in very tiny letters at the bottom of the page: "This ad paid for by the friend"—friend, singular!—"of Arnold Schulman and the Society of Battered and Abused Screenwriters." Everybody laughed, and I didn't work for three years.

That must have been really painful.

Not really. I was in my traveling mode . . . until A Chorus Line.

I gather that was also a messy situation.

The strange thing about this one is that for years, writer after writer tried to find a way to turn the musical into a movie, and nobody could. Finally, I came up with a surrealistic approach that [the producers] Norman Lear and Jerry

Perenchio must have liked, because they put up twenty-four million dollars of their own money to make it. Richard Attenborough must have liked it, because he agreed to direct it; but for reasons known only to him, Attenborough threw away the script completely and tried to photograph the play.

In addition to this disastrous decision was a set of circumstances nobody could have coped with. After Lear and Perenchio put up the money and the picture was being made, they sold their company to Columbia, and Columbia wanted nothing to do with A Chorus Line. So every single element was fighting with every other element, and all the pressure landed on Attenborough. Columbia versus Embassy versus the two producers; everybody disagreeing with each other about the casting, this and that, about everything. How Attenborough survived it, I have no idea, but he is the most decent man in the world, a truly warm, intelligent, beautiful human being.

I'll always remember one meeting we had with the producers over the results of the screen tests; we were going make the final decision as to who would be the leading lady. The meeting was at the Regency Hotel in New York. I offered my opinion, and one of the producers said, "Who asked you? You have nothing to do with this. Go to your room!" "Go to your room"? Like a little kid. I was stunned. I said, "You're right; it's none of my business," and I left. Attenborough had to leave the next morning on the Concorde to go back to London for some reason, and on his way to the plane, early in the morning—he is so sweet and thoughtful—he called me and told me what happened at the meeting after I left and thanked me for my suggestion. In contrast to the asshole producer.

When we had the first preview in San Diego, the list [of invited guests] came back, and my name wasn't on the list. My agent thought it was a mistake and called up one of the executives, another one of the producers. This producer said, "He's the writer. Writers don't go to previews." My agent called Attenborough, who got angry and called them on my behalf. "What the hell are they talking about? Of course, he's going to the preview!" What a putdown—Won Ton, the Players, and now this!

What a horrible litany of experiences.

We're living in a madhouse here. If they take your script, you have to pray the director will understand it, the actors won't fuck it up, they won't throw another writer in, they'll merchandise it okay . . . there are a hundred thousand things that can go wrong, and barely one thing that can go right. The odds are so much against making a movie. Making a good movie is worse odds. Making a great movie is virtually impossible.

Yet you;ve spent your entire career as a writer for hire.

Yeah, and I hate myself for it. I really do. The sixties were great. From then on, it's been downhill.

You could have made different choices a long time ago.

I know. I regret it bitterly.

I understand that, dating back to the 1960s, you have been doing some script doctoring under the table.

It's interesting work. I never take credit for it.

Isn't doctoring scripts a little bit like selling your soul?

No, it's preserving yourself. You're doing it for the sake of the work, which is pure Zen. There's a purity about it. Either I would like to doctor and stay anonymous, or have complete mutual collaboration. The in-between is where it's awful. In any case, I've never taken any money for doctoring.

Most people do it purely for the money.

I do it as a friend, and I won't do it unless as a friend. If somebody comes to me and I like the material and I see how I can make a contribution, I'll do it. But I don't take any money for it. And I won't work on a script behind the back of another writer. Many times, I've turned work down because the first writer on the project was a friend of mine.

Can you tell me which are the better-known films you doctored?

There was one giant hit I was involved with in the 1960s—just as a friend. And there were other films of more or less merit. But I don't want to give titles. As I say, I don't take any money, and I don't want any credit.

In Hollywood, taking no money and no credit, that must be regarded with great suspicion.

I'm sure everybody thinks I'm crazy. Ask David Brown. I don't care what they think. I have to live with myself. When I turn in a script—this must have happened a dozen times over the years—and they say, "Well, here's my notes," I have been known to say, "I don't want to do any of your notes." They say, "Well, you've got to do our notes . . . " I say, "No, I don't. I'll give you your money back. Let's tear the script up. If you don't like what I do, I don't want your money." The one thing I make clear is, give me my script back.

That brings us to Tucker.

Thank God for Tucker. That saved my sanity.

How were you brought in on Tucker?

Curiously, I got a phone call from Francis Coppola, who I had met only once on an airplane. He told me all about [the 1940s automobile visionary Preston] Tucker, whom I had never heard of. I told him I hated cars. "I would like to work with you, Francis," I said, "but I really hate cars." He said, "Will you meet with me and George Lucas, and talk about it?"

Why was Coppola so insistent about having you?

I don't know. I assume it is because I had worked with Frank Capra, and he wanted it to be a Capraesque picture. George said, "The film is not about cars. It's about Francis. Why don't you go live with Francis in Napa for a few weeks and then let me know?" I did that, and then I realized of course the film was about Francis, and told them I'd love to do it. I had to endure all the car bull-

"That saved my sanity": Jeff Bridges in Tucker , directed by Francis Coppola.

shit for the character—who was Francis. That part [of the concept] didn't come off too well because of the casting.

I was told by producer Fred Roos that all along they were thinking of Jack Nicholson in the starring role.

They talked about Jack Nicholson. I just assumed it was going to be Harrison Ford. When we got to that point, both proved too expensive.[*]

Did Coppola, himself an excellent writer, make script contributions?

Extremely valuable contributions. [He might say,] "There's a hole here, we need to fill this in . . . ," or "I've found this actual Tucker promo; see if you can weave it in . . . "

In a way, Coppola makes modernist movies, but on the other hand, he's a throwback to an old-fashioned way of screen storytelling.

Absolutely. He's a wonderful person. It drives me crazy that the idealists willing to take risks get knocked on their asses, while the safe guys—who do the movies that make all the money, and who have all the power—get none of the aggravation.

Tucker was a wonderful experience. Suddenly, it was back to the old days, working closely with Francis and being on the set, watching him direct and talking about scenes. Not a line was changed. I was there for rehearsals and had to leave for a while; then I came back when he was shooting; I tiptoed up to the script supervisor, because Francis is so notorious for improvising, and

* Jeff Bridges ended up playing Tucker.

said, "Just break it to me gently—what did he do with the script?" She said, "I've been working with him for x number of pictures, and I've never seen this happen before. An actor will ask, 'Can I try the line this way?' and he'll think for a minute, then answer, 'Well, why don't you do it the way it's written?'" I went up to Francis and said, "Francis, you're ruining your reputation. Why are you doing this?" I'm sorry, this sounds self-serving—I should have told it in a different way—but he said something to me that not many people in this town understand: "A hundred hacks can rewrite another hack, and nobody'll know the difference; but one good writer cannot rewrite another good writer because their rhythms are different."

They don't know that in Hollywood. They don't know about rhythms. They know how it says on page 26 of all these books about how to write a screenplay that you have to have a turning point. I myself don't know what the hell a turning point is. When I heard about a turning point in a meeting for the first time, I said, "What the hell are you talking about?" They told me that in the books on how to write a screenplay, they all say that on page 26, or whatever, you have to have a turning point.

The making of Tucker was marvelous. I loved what Francis did with the script. We knew it was a gamble—that a lot of people wouldn't get it; that we were doing some things deliberately, bad thirties acting and speeded-up [action]. But it is exactly what we set out to do. I love that movie.

Who is the credited cowriter, David Seidler?

Out of nowhere—I was in Venice or some place—I got a call from my secretary that this guy Seidler was suing for credit. I had never heard of him before. I didn't even take it seriously; I just dictated a little note about how I wrote the script. When I got back, I found out that he had been given cowriting credit. I was never allowed a rebuttal to the Writers Guild.

It turns out that ten years earlier, he had been hired as a research guy [on the project], and he had asked Francis, "Do you mind if I put the whole thing in screenplay form?" Francis said, "No, of course, go ahead, kid." His script started with Tucker at six years old and included every detail of the man's life until the day he died. Since it was a real-life story, obviously there were going to be incidents similar to those in my script—like Abe Lincoln: if ten writers write different scripts about Abe Lincoln, in all of them there's going to be a wife named Mary and a Civil War, and Abe's going to get shot in the end. This business of giving Seidler credit shocked me. The worst part of it is, when the film was coming out, I was helping out with publicity and speaking somewhere to some class of would-be screenwriters, and all they were interested in was how did the other guy steal the credit? Could they steal a credit? How?

At the opposite end of that type of crazy situation is Jay Presson Allen and Funny Lady, where I couldn't persuade the Guild to give her the credit she deserved, or films like Won Ton Ton and Players— where, no matter what, I wasn't permitted to take my name off the screen. Believe me, I was pissed off

about the credit grabbing on Tucker. I'm still pissed off. That is one instance where every word of the script is mine.

I'm struck by how few writers who were here when you first came to Hollywood, in 1956, are still around and active.

Almost none. I don't know why. There's no sense of community out here, at least for me. I don't know if there ever was in Hollywood that marvelous sense of community which there was in New York when I was starting out. I miss that terribly. Probably it's me. I don't belong anywhere. I have not integrated myself into the movie community or the theater community or the writer community. I don't stay put long enough, I guess. I have realized only recently that everybody here in California thinks I live in New York, and everybody in New York thinks I live in California. Usually I'm not in either place. I've got this house mainly as a home for my books.

You never actually moved to California?

Never. At first I always lived in the East. I'd come out here to do the work and go back. Now I do the work and head for another country.

You made the decision to work in movies, but—

I still didn't want to live here.

Why is that?

The usual answer. I prefer cities where I can walk on the streets and see people. Where, if I feel like going out at three in the morning for a sandwich, I can do that. All the cliché reasons. And when I'm not working, I'm traveling. That's my other life. As a consequence, I really have become the outsider—that little boy who didn't have patches on his overalls. I realized not long ago that my life has come full circle.

Around the time of Goodbye, Columbus you were flirting with becoming a director. What stopped you?

I haven't had a hit since then. If I had a hit, I would have had the clout to go in and say, "If you want my next one, I direct it."

If Goodbye, Columbus was your last hit, how have you survived financially?

There have been hot streaks where I've had enough to live on and spent it all, but fortunately, I've always been able to command a good price. My son worries about me all the time. But my analogy to him is: Just imagine that I'm a yacht salesman. All I have to do is sell one yacht every three years, and I'll be fine. I'm not selling chewing gum.

I have been writing a movie of And the Band Played On, the book about AIDS by Randy Shilts. I should say I wrote it as a movie, but it will be produced by HBO for cable. The intention is that it become one of their event pictures. Incidentally, my name is on the project as coproducer, and I made it clear I didn't want that to be in name only, only if I could actually function in that capacity. I did the script for virtually no money—which I donated, and I don't have the money to donate. I wanted it to be a pure experience.

"A pure experience": from left, Ian McKellen, Matthew Modine, and Lily Tomlin in

the telefilm And the Band Played On. Adapted from Randy Shilts' book.

What I thought would take two months of time has taken almost two years of my life, so far. One director came and went—I won't go into all the ugliness—then another director. I worked with the new director day and night, rewriting. Then another director came along and another director.[*] One director wouldn't even talk to me. The irony is, this is one thing I have done for

* And the Band Played On was eventually directed by Roger Spottiswoode.

altruistic reasons, as an indictment against greed, ego, and bureaucracy, and I have gone through a nightmare of greed, ego, and bureaucracy while doing the picture. It's taken so long [so far] that I have to flagellate myself to go back to work on it. But it will happen.

I've got a number of spec scripts that I really want to do, all of them in various stages. Wherever you look in this house, you'll see a pad and a pen—in the bedroom, the toilet, wherever. If I get an idea, I immediately write it down. Each project is in a cardboard box, and I just throw the idea in the box. When I get some time and the inclination to work on this one instead of that one, I do. It's hard to say which is going to be first.

If they don't sell, I'll definitely switch careers. I would go into novels now if I could afford it. As a novelist, I have no track record. I've written two based on the movies of A Hole in the Head and Love with the Proper Stranger, and I've written one nonfiction book about an Indian holy man that Viking published [Baba (New York: Viking, 1971)]. Any of these spec scripts, if they don't work, would make a good novel. I'll just do doctoring and write novels, because novels are yours. Good or bad, they're yours.

If it's not going to be fun, there's no point writing scripts anymore. I can't even watch today's movies—how can I write them? I would rather be living with the cannibals in New Guinea than sitting here writing scripts in this monastery. Although the euphoria, when you're doing well and you're in that extradimensional place—nothing can top that—that's a high that no drug, sex, or food can beat. Just as nothing beats the agonies when it's going awful.