Preface

Given the explosion of informal economic activity in Africa in the 1980s, the study of the informal economy by social scientists appears to be woefully slow, trailing developments. In Zaire, Janet MacGaffey (1987) noted that one consequence of the growth of the informal economy has been the emergence of a new mercantile class that has been changing class configurations in that country. Naomi Chazan (1983, 196) argued that in Ghana the degree of internal organization in the informal economy reflected the degree of disarray in the formal system. Robert Bates (1981), Frank Ellis (1983), and others have described the magnitude of evasion of official crop-marketing boards and the predominance of parallel market trade in the African context.

If one considers the far-reaching political and economic consequences of the informal economy suggested by these authors, it seems remarkable that so few political scientists and economists have found the informal economy in Africa worthy of greater attention. Instead, scholars have generally been content with making the perfunctory observation that the informal economy creates problems in the use of official statistics, without fully exploring the implications of such claims.

Yet since the late 1970s the informal economy has become an increasingly significant political, economic, and social phenomenon in many African countries. People have become increasingly forced to rely on their own resources while lessening their dependence on the state and the formal economy. In Tanzania, informal economic exchanges are more common than are similar transactions in the formal economy. For urban dwellers, employed and self-employed alike, the informal economy accounts for what the majority of people do to make most of their income. During periods of commodity shortages and hiked prices, the official figures on real incomes

could not possibly have been accurate, because they were generally based on consumer price indexes that primarily reflected official prices rather than the higher unofficial prices. Ratios of highest to lowest income levels generally only consider formal salaries and wages, not the large gaps between real incomes derived from informal businesses. Similarly, figures on crop exports reflect only those crops sold through official marketing bodies and not the large quantities that are channeled through parallel markets. Even many of the recent studies of the informal sector, amazingly, do not capture in their samples the largest numbers of micro-entrepreneurs who work in individually owned businesses; nor do they always include the large numbers of women, whose household tasks, farming, and business activities may be so intermeshed that they elude survey categories. These observations clearly have enormous implications for any conclusions drawn about economic growth, equity, and resource distribution.

This study focuses on the political challenges of the informal economy rather than on problems related to accounting, as important as those problems are. Some have characterized the informal economy as a form of disengagement from the state and of resistance to the state (Azarya and Chazan 1987, Bayart 1986, Chazan 1988). This book, however, shows that the informal economy is more than simply disengagement from the state. Under extreme economic duress, people have challenged the existing political and economic order by engaging in activities that in themselves became new economic and institutional resources. In doing so, they helped bring about changes in the rules of the game. The study explores these new economic resources (for example, new products, services, sources of credit, and savings). At the same time, this study looks at the moral code within which much of this informal economy operates and shows how it came into conflict with the existing political order and ideology in Tanzania. The strengthening and creation of alternative institutions reflecting a different set of rules became in itself a form of resistance.

My own interest in the informal economy started, in part, with an empirical problem when I began to question how urban dwellers in many African countries were surviving on the reported official wages when the cost of living was many times greater than those wage incomes. When I returned to Tanzania (I had grown up there from 1960 to 1974) to carry out my fieldwork in 1987, the discrepancy was all the more incomprehensible. Official wages did not correspond even remotely to the cost of living regardless of the level of formal wages. As I had suspected and as all Tanzanians knew, informal incomes made up the difference. But

what I had not expected was the extent to which people relied on informal incomes.

What I also did not anticipate was the interest Tanzanian people I interviewed had in understanding the informal economy. Individuals knew how they themselves were making ends meet, and they had some idea of how their relatives, neighbors, and friends were surviving; but few had a sense of the broader picture, and many expressed their curiosity about this to me. In fact, in many of the poorest neighborhoods where I carried out a survey, many people, some of whom could barely read, requested a copy of my report and gave me their address. This interest in the research topic and the importance people themselves placed on the informal economy gave added urgency to the study.

As I began to fathom the enormity of the informal economy and its centrality to the Tanzanian economy, I was forced to consider its broader political, economic, and social implications. To begin with, participation in the urban informal economy had resulted in the Tanzanian case in massive reversals in dependencies and reversals in the direction of resource flows at many different levels: away from the state and toward private solutions to problems of income, security, and social welfare; away from reliance on wage labor and toward reliance on informal incomes and farming; and a gradual shifting of migration patterns with increasing new movements out of the city into the rural areas. Similarly, relations and patterns of obligation in the household were being transformed, with greater resource dependencies on women, children, and the elderly, where only a decade earlier urban women had mostly relied on men for income, children on their parents, and the elderly on their adult children.

Women's heightened economic activity also gave greater prominence to alternative logics of economic decision making, which emerged among the poor to confront government policies that worked against them in their struggle to survive. The struggle against the harassment and bribing of vendors by the militia, against unjust licensing policies, and against restrictions on sideline businesses and other such conflicts brought to the fore competing economic rationales. The embeddedness of narrowly defined economic activity in social and cultural life, in household activities, and in activities involving the regeneration and sustenance of life made the state's intrusions all the more oppressive.

The informal economy helps explain some of the internal circumstances that allowed Tanzania to embark on a program of economic reform and austerity at a time when urban dwellers, in particular, were suffering enormous hardships. People's reliance on their own solutions explains how

they were able to cope when the government launched economic restructuring programs that involved cuts in social-service expenditures and in food subsidies, continuing low wages, and some layoffs. Although this study does not attempt to justify these cutbacks, it shows how informal economic strategies meant that people did not experience the full force of these austerity measures.

At the same time, urban dwellers resisted policies that infringed on their ability to carry out informal income-generating activities through strategies of noncompliance and "quiet, everyday resistance," to borrow a term popularized by James Scott. In response, policy makers made a number of concessions to people operating in the informal economy, making it easier for them to pursue such activities. This loosening up came at a crucial time, when international donors were pressuring the government to adopt austerity measures that otherwise would have made life, especially for urban dwellers, virtually untenable. Most of the pressures for liberalization, privatization, and legalization of various informal economic activities discussed in this book, with a few exceptions, were distinct from the economic reforms pushed by international financial institutions. Rarely has the discussion of economic reform in Africa considered these internal pressures and domestically initiated reforms.

These developments inevitably had repercussions for the political order. Key tenets of Tanzania's statist and socialist orientation began to unravel in the face of pressures for greater political inclusiveness and local control through the legitimation of informal economic activities. For example, the 1991 Zanzibar Declaration effectively undid the Arusha Declaration, which had been promulgated by the ruling party, Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), in 1967. TANU had sought through the Arusha Declaration to eliminate bases for class inequality by discouraging foreign investment and by forbidding capitalist practices of party members, middle- and higher-ranking civil servants, and government officials.

The study of the informal economy adds a new dimension to the study of state-society relations, which in the literature on African politics has been dominated by state-centric approaches, even given the emphasis on civil society and nongovernmental actors in the 1990s. Much of the current debate has focused on the demise and weakness of the African state, and less emphasis has been placed on why people themselves have withdrawn from the state and have resisted state policies and development programs through strategies of noncompliance. Instead, scholarship has focused on elites and their abuses of power, on patterns of personal rule, and on patron-client relations.

The approach of this study is to look at the whole network of interactions between various social actors, from households to networks, voluntary associations, the ruling party, government institutions, the military, the formal private sector, international lending institutions, and all of the other significant actors on the political stage in Tanzania. Politics in this context involves struggle, negotiation, and accommodation over how resources will be allocated and what values, ideologies, symbols, and institutions will predominate. The challenge is not to replace past top-down approaches to the study of politics or development with an approach that would make the state irrelevant. The aim is to focus on areas where "constructive reciprocities," as Goran Hyden (1992) calls them, have been established and to learn from the experiences of those who have challenged and overcome existing structural limitations.

It is, of course, much easier to identify and focus on the myriad economic constraints people face in their daily lives and on the obstacles that stand in the way of making the state responsive to the needs of people. What the study of the informal economy shows is how people have adapted and persevered amid extreme adversity. People did not wait for the government, the ruling party, donor agencies, or anyone else to solve their problems. They took matters into their own hands and tried to reconstruct the world around them to the best of their ability to suit their needs. They did so even when it meant having to skirt laws that undermined their ability to pursue a livelihood. The government eventually had to take note of some of these forms of resistance. More than once I heard government authorities say that the people led the way with their strategies and that the leaders followed behind with their policies, by legalizing, privatizing, and legitimating activities that had already been "sanctioned" by the people. Aspects of these economic pressures even contributed to some of the political liberalizing trends that were under way by the early 1990s, as Tanzania sanctioned multipartyism, the press gained greater freedom, nongovernmental organizations were being encouraged, and other signs of political openness became visible.

As such new reciprocities were being forged, new conflicts, in the form of tensions between religious and ethnic groups and between classes were surfacing. At the root of these conflicts lay the debate over how best to attain equity and economic justice, issues that confront most societies attempting to reverse decades of heavy state-directed top-down approaches to development and growth.

The book begins with a discussion of the informal economy as a manifestation of societal noncompliance with the state, as a tool for institutional

change in challenging state norms of fairness and economic justice, and as a means of creating new institutional resources. Chapter 1 grapples with the problems of using reified categories of "informal-formal economy" and "state-society." It also explores some of the ways in which understandings of the informal economy have not sufficiently differentiated licit activities from illicit ones. Similarly, ideologically charged notions of the informal economy have not adequately taken into account the diversity that exists from one part of the world to the next regarding the informal economy, the reasons for its existence, and its potential.

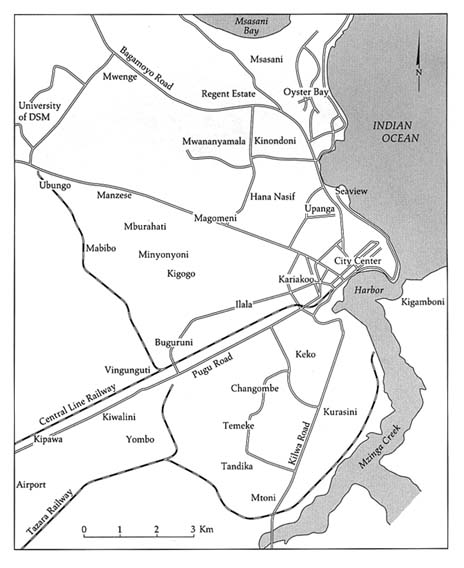

Chapter 2 provides a historical context for the rapid changes that took place in the 1980s in Tanzania with the decline in real wages, flight from wage employment, intensifying rural and urban linkages, the growth of income-generating projects, and the growing importance of informal incomes in families with wage earners in the formal sector. The chapter also provides a general background for Dar es Salaam and for Manzese and Buguruni, the two parts of the city that were the focus of the study. Chapter 3 gives a general outline of the shifting boundaries of state control of the economy. It shows how the postindependence state expanded its jurisdiction, only to retreat in the 1980s as a result of economic crisis, a loss of state resources due to failed government policies, pressures from international donors, and popular pressures of noncompliance that created spaces for people within which to establish new institutions.

The next chapter explores some of the conflicts between coalitions that polarized party and government leadership over the direction and pace of economic reform. It identifies the societal winners and losers in the reform process and explores the paradox of urban workers who had the most to lose from these reforms yet seemed relatively unaffected by the various austerity measures that were imposed on them. The informal economy, which had already emerged in response to economic crisis, becomes an important reason in explaining this relative urban immunity.

Chapter 5 looks at the changing household dependencies in which women, children, youth, and the elderly have taken on greater responsibilities in providing income, while male wage earners no longer are the main source of income for the urban household, as they were prior to the 1980s. The chapter also explores alternative economic decision-making strategies that characterize much of the informal economy but are especially apparent in the way women go about their business activities. Chapter 5 highlights the embedded nature of economic activity in the totality of life experiences and in society.

Chapter 6 shows how the state's rules of the game are challenged and

changed by people who refuse to comply with bans on microenterprise activity, on sideline activities, on the operation of private buses, and on other activities that are basic to their efforts to gain a livelihood through what they consider legitimate means. The chapter shows how the state retreated and changed the rules in the face of such popular pressures. Chapter 7 shows how these pressures manifested themselves in conflicts among the country's rulers, bringing to a head an ideological conflict between the party and government leadership that led to the dismantling of the key ideological tenets. The concluding chapter suggests some of the institutional conflicts underlying the changes that occurred in the 1980s regarding the informal economy. It explores the implications of these dynamics for understanding state-society relations and problems of local governance.

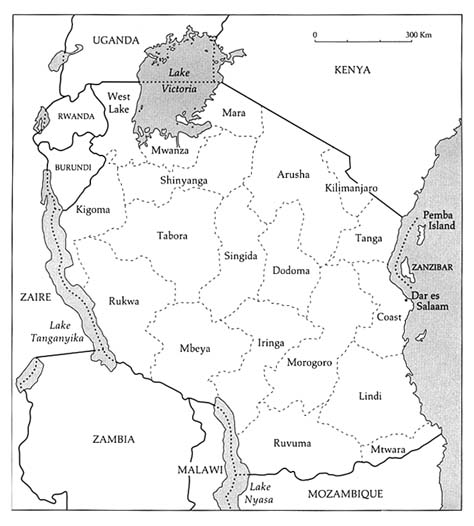

Map 1. Regional boundaries of Tanzania.

Map 2. Major wards of Dar es Salaam.