Preferred Citation: Prichett, Frances W. Nets of Awareness: Urdu Poetry and Its Critics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft10000326/

| Nets of AwarenessUrdu Poetry and Its CriticsFrances W. PritchettUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1994 The Regents of the University of California |

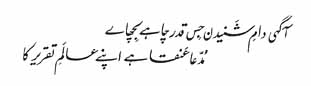

My realm of words shelters the imaginary bird.

Preferred Citation: Prichett, Frances W. Nets of Awareness: Urdu Poetry and Its Critics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft10000326/

My realm of words shelters the imaginary bird.

Acknowledgments

Everything I’ve ever done with Urdu has helped to guide me toward this book. So first of all I thank my teachers: Moazzam Siddiqi and Bruce Pray at Berkeley, C. M. Naim at Chicago, and Khaliq Ahmad Khaliq in Lahore. Their knowledge, dedication, and encouragement have been most precious gifts. And I pay tribute also to my literary mentor Ralph Russell, lifelong foe of academic pretentiousness and unnecessary jargon, who insists that scholarly writing should be kept as open as possible to all interested and intelligent readers. Since he has always practiced what he preaches, his lucid, straightforward books have influenced me from the beginning.

As ever, I owe thanks to my own family, and to the whole community of Urdu-lovers, many of whom have been generous with their time and help on this project. In Karachi, Dr. Aslam Farrukhi presented me with a copy of his own indispensable two-volume biography of Azad; he and Janab Jamiluddin Aali, Dr. Farman Fatahpuri, Dr. Asif Aslam, and the whole group at the Anjuman Taraqqi-e Urdu provided me with an excellent forum for trying out some of the ideas argued in this book. In Lahore, I had the good offices of old friends like Begam Altaf Fatima, and Janab Ahmad Nadeem Qasimi very kindly found me a copy of Dr. Farman Fatahpuri’s out-of-print tazkirah book. In Delhi, Maulvi Niyazuddin and his son Nizamuddin of the Kutubkhanah Anjuman Taraqqi-e Urdu were an invaluable source for rare books, new friends, and other Ġhanīmats. Dr. Gopi Chand Narang in Delhi, and especially Dr. Naiyar Masud in Lucknow, have helped with advice and counsel. I am also grateful for the useful suggestions and general moral support provided by interested friends and colleagues in America, especially Susham Bedi, Aditya Behl, Nadine Berardi, Michael Fisher, Laura Freseman, William L. Hanaway, David Lelyveld, Philip Lutgendorf, David Magier, C. M. Naim, Carla Petievich, Bruce Pray, Ibrahim Quraishi, David Rubin, Vijay Seshadri, and the late Barbara Stoler Miller, whose recent death has been a sad loss to us at Columbia. Any book is a node in a network of such practical and intellectual exchange, and I have received more kindnesses over the years than I can even record.

The National Endowment for the Humanities provided a research fellowship that gave me a year (1987-88) of leave from teaching so that I could lay the groundwork for this book. Special thanks are also due to my friends and colleagues at the Middle East Center and the South Asia Regional Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania, who during the last few years have played the largest role in bringing Shamsur Rahman Faruqi to this country several times for talks and seminars. The South Asian Area Center at the University of Wisconsin at Madison also invited him for a month-long lecture series in 1990.

Lynne Withey of the University of California Press did much to make this book possible; I’m grateful for her encouragement and support. One of her best deeds was to suggest that I work with Pamela MacFarland Holway, whose thoughtful advice and insight helped to shape not only the intellectual contours of the book, but its visual design as well. My friend Adil Mansuri was kind enough to provide some of his elegant calligraphic creations.

In the making of this book my best colleague and friend, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, has played so substantial a role from start to finish that it seems almost inappropriate merely to thank him. He not only suggested many refinements and saved me from many errors at every stage of my work, but did much of the original research on which the middle third of the book rests. As always in our long-standing collaboration, it is both an honor and a pleasure to work with him closely enough to be so deeply indebted. Any remaining errors are, needless to say, mine alone.

A Note on Transliteration

The letters of the Urdu alphabet have been transliterated as follows:

For the sake of consistency, Persian words have been transliterated as they are pronounced in Urdu. Indic words have been treated as though they were written phonetically in Urdu script.

alif as: a, i, u, ā b p t ṭ ṡ j ch ḥ ḳh d ḍ ż r ṛ z zh s sh ṣ ẓ t z ‘ ġh f q k g l m n vā’o as: v, ū, o, au h ī baṛī ye as: y, e, ai nūn-e Ġhunnah: ñ hamzah: ’ iẓāfat: -e

Preface

Long ago at Berkeley, when I was just learning to read the Urdu script, my teacher introduced the class to the poetry of Ġhālib. It was much too hard for us. We spent a whole hour grappling with a single two-line verse. But then, as a reward, we heard it sung by Begam Aḳhtar—and I was hooked. These little verses were dense, tight, intricate structures, made of beauty and energy held in perfect balance. They resonated so well with my own inner life and my own sense of poetry that I loved them even before I understood them. I knew I wanted more.

In the library I found just the sort of book I had been looking for: Muhammad Sadiq’s magisterial A History of Urdu Literature (1964), published by the Oxford University Press in India. East meets West, I thought, and here is the best of both worlds: a book in English, equipped with references, notes, index, diacritics in the Western scholarly style—by an author who comes from within the Urdu tradition, who in fact is a senior professor at a college in Lahore. Here is a much more knowledgeable ghazal lover who will interpret the tradition for me, and will share with me an insider’s appreciation of the poetry.

Alas for my innocence. Professor Sadiq made it clear that I was wrong to value the ghazal so highly. For the ghazal has had a rotten streak from the beginning: it was “tainted with narrowness and artificiality at the very outset of its career.” As a result, it has innumerable flaws. The ghazal “lacks freshness”; it “has no local colour”; its deficiency in “truthfulness,” “sincerity,” and a “personal note” has made much of it into a “museum piece.” Its imagery is “fixed and stereotyped”; it is “incapable of showing any feeling for nature”; it displays “fragmentariness” and is “a patchwork of disconnected and often contradictory thoughts and feelings.” In fact it is generally held to be “the least poetic of all forms, because it least admits of inspiration,” and there is “a large element of truth in the argument.” It envisions love as “a torture, a disease,” a “morbid and perverse passion”—a view that is a “legacy from Persia” and is “ultimately traceable to homosexual love which had taken deep root among the Persians and Persianized Arabs.” Furthermore, over time the ghazal has gone from bad to worse. It has developed “wholly in the direction of fantasy and unreality”: “facts give way to fancies,” and the imagination explores “curious byways” as the ghazal evolves “in its downward career.”[1]

Although Professor Sadiq recognizes that the ghazal has “strong assets,” he sees them as outweighed by even heavier liabilities. He sums it all up in a phrase that has lived in my mind ever since—and has goaded me into writing this book. The ghazal, Sadiq says, “stands very low in the hierarchy of literary forms.”[2] This is so obviously an erroneous and wrongheaded statement that refuting it is not my main goal; the poetry itself is a more than sufficient refutation. Rather, I want to inquire how this judgment has come to be made. Even if there could be such a thing as “the” hierarchy of all genres (which there cannot be), and if anyone had the authority to define it (which no one does), why would anyone rank such a sophisticated, powerful genre as the ghazal, popular for over a millennium in many languages, near the bottom? And even more to the point, why would someone like Sadiq make such a harsh and hostile judgment? This poetry had, after all, been handed down for generations as one of the chief glories of his own cultural heritage, and he obviously valued his heritage enough to spend many years studying it and writing books about it. Why did he devote years of his life to this heritage—and then produce a sweeping denunciation of the genre that lay at the heart of it? Instead of providing a subtle, nuanced analysis of the ghazal, why did he attack it with a blunt instrument?

To my further surprise, I found that Sadiq was far from alone in his views. Classical Urdu literature has very commonly been presented in English either disdainfully or apologetically—or both. Of course, such modes of presentation not only irritate the serious student, but also discourage the newcomer from pursuing the subject further. The distinguished Urdu scholar Ralph Russell has recently expressed his own exasperation at this state of affairs in an article called “How Not to Write the History of Urdu Literature”—an article replete with horrible (and humorous) examples and offering among its conclusions the polite advice, “If you don’t think much of Urdu literature, please don’t go to the trouble of writing a history of it.”[3]

In Urdu too, as I gradually realized, Sadiq’s views were only a relatively complete inventory of attitudes many critics held in part. Disdain has sometimes been expressed not only openly but even extravagantly: according to one well-known critic, the ghazal is “a half-barbarous form of poetry.”[4] By contrast, defense of the ghazal has usually been halfhearted at best. Most apologists have freely conceded such fundamental defects as artificiality, lack of unity, and so on, and have then sought merely to reduce the charges by pointing out some mitigating circumstances and redeeming features.[5] Or else they have sought to justify the ghazal not as poetry, but as a vehicle for conveying an alleged political or religious message.[6] “Even today,” as one perceptive critic recently put it, “we are ashamed of the greater part of our literary property—or we do not consider it worthy of esteem.” The result is that “our tongues never tire of finding fault with our cultural possessions.”[7]

Why could I, knowing so much less Urdu, admire and appreciate Ġhālib more than many of his cultural heirs? How far back did this critical intolerance toward the ghazal—and other traditional genres—go? I eventually traced the attitude straight back to the earliest (and still much the most important) history of Urdu poetry, Āzād’s Water of Life (1880), and found it reaffirmed and elaborated in the earliest (and still much the most important) work of modern Urdu literary criticism, Ḥālī’s Introduction to Poetry and Poetics (1893). As I investigated the lives of Azad and Hali,[8] I discovered that these two uniquely influential literary pioneers had shared certain formative experiences both in their youth and afterward. Gradually I came to understand why and how their views had developed. They who had inherited the mansion of classical poetry made a desperate resolve: to condemn large portions of the structure, in order to shore up and renovate the rest. Against the background of their lives, such a resolve made sense. But over the past century it has also done immense cultural harm—and this harm continues into the present. When I discovered that Muhammad Sadiq, my original bête noire, had in fact written his doctoral dissertation on Azad, I knew that the wheel had come full circle.

Nets of Awareness is a study of an episode in the cultural and literary history of late-nineteenth-century North India: a look at how the classical ghazal, which for centuries had been the pride and joy of Indo-Muslim culture, was abruptly dethroned and devalued within its own milieu, and by its own theorists. The break with tradition was so sharp that nowadays some aspects of the ghazal are obscure, and others even markedly distasteful, to most modern readers. I argue that the cause of this abrupt “paradigm shift” was not ultimately literary so much as political. The violent “Mutiny” of 1857, and the vengeful British reaction to it, destroyed the old world of the Indo-Muslim elite. After 1857, the victorious British had the only game in town: they were obviously, “naturally,” superior, and they made sure everyone realized it. Azad himself, in another context, described the result: “The important thing is that the glory of the winners’ ascendant fortune gives everything of theirs—even their dress, their gait, their conversation—a radiance that makes them desirable. And people do not merely adopt them, but are proud to adopt them. Then they bring forth, by means of intellectual arguments, many benefits of this.”[9]

Such adoption of a new culture may be a fine thing; certainly both Azad and Hali were officially and strongly committed to the benefits of Westernization. But however good a face they managed to put on it, the result was clear: after 1857 they found themselves having to perform radical surgery on their own culture, to enable it to survive in a world defined by the victors. Azad and Hali set out to replace their inherited Indo-Persian concept of poetry with what they understood to be the contemporary English one: a Wordsworth-like vision of “natural” poetry.

If Wordsworthian poetry was the touchstone of naturalness, however, the whole Indo-Muslim poetic tradition was bound to appear “unnatural” in comparison—not just literarily decadent, artificial, and false, but morally suspect as well. And if, as many English writers argued, poetry was inevitably a mirror of society, then the cultural rot must go much deeper. The result was a sweeping, internally generated indictment with which Urdu speakers have been struggling ever since. A History of Urdu Literature was reprinted in 1984, shortly before its author’s death, in an expanded second edition. Professor Sadiq added much new material; but he did not change a word of his harsh attack on the ghazal.

The present study has three parts. In the first part I locate the lives of my two central characters, Azad and Hali, within their cultural and literary setting; in the second part I seek to reconstruct the orally transmitted poetic concepts that Azad and Hali inherited—concepts that are now little known and even less understood; in the third part I analyze the new anticlassical poetics that Azad and Hali defined with such urgency and power.

I hope, of course, that this book will be useful to lovers of Urdu literature both here and in South Asia, and to scholars of North Indian culture and history. But I have also tried my best to make the subject as vivid and interesting to others as it is to me. I will be delighted if people who know little or nothing about Urdu literature can find in this book a starting point. For this reason, I have included not only a glossary of key literary terms, but also an appendix containing an example of a ghazal, literally translated and with its parts explained. Also for this reason, I have used English sources wherever possible, so that the reader can consult them independently; usually, however, there aren’t any, and in such cases all translations are my own.

This story takes place in North India only a little over a century ago, the blink of an eye in historical time. Worlds were in collision. The powerful momentum of the advancing British Raj encountered the political inertia of the declining Mughal Empire. The irresistible force met the heretofore immovable object—and rolled over it. Azad and Hali, survivors of this great historical collision, were absolutely determined that their literature—and with it their culture—would not die from the shock. Their urgent attempts at triage, surgery, and sometimes euthanasia were not always successful. But their larger purpose was achieved. The Indo-Muslim community survived its darkest hours, learned to play the new game by the new rules, and was able once again to face the future with purpose and hope. Now, a century later, it can consider reclaiming some of the best achievements of the old game.

Our own generation can take pride in a widening range of cultural encounters that has opened over time to more and more people. We expect cultures to clash, and we try to appreciate the dissonances. But we also know that (as Azad put it) “if you examine the temperaments of individual men who live thousands of miles apart and in countries with different characters, you will see, since human nature is one, to what extent their thoughts resemble each other’s” (46). Across the continents and the decades I salute Azad and Hali: with their backs to the wall, they had the courage to fight for survival and renewal. They tried desperately to reorganize their culture into lines of defense that could resist the Victorian onslaught. Even when they attacked their own poetry most bitterly, their love for it was never in doubt. And even when I disagree with them most strongly, I know that they would understand my own larger purpose. For we can now see that the poetry itself has stood firm over time. The Victorians are dead, and the ghazal lives.

Or at least, the British Victorians are dead; but many South Asian Victorians remain. They view the ghazal through the special distorting lenses provided by Azad and Hali—yet in many cases, such is the power of the poetry, they guiltily find themselves loving it anyway. This book is dedicated to the memory of Azad and Hali, and to everyone who loves classical Urdu poetry. For nowadays cultures belong to those who choose them. And I am proud to consider myself an heir to the rich and inexhaustible tradition of the ghazal.

Notes

1. Sadiq, A History of Urdu Literature, 14-19, 22, 24, 27, 29.

2. Ibid., 20.

3. Russell, “How Not to Write the History of Urdu Literature,” 9. Russell notes one honorable exception: Urdu Literature, by D. J. Matthews et al. Russell’s own work deserves pride of place on any such list; I would also add Ahmed Ali’s general introduction to The Golden Tradition and Carla Petievich’s more specialized study of the “two-school” theory.

4. Kalīmuddīn Aḥmad, Urdū shā‘irī par ek naz̤ar, 69.

5. Mas‘ūd Ḥasan Riẓvī “Adīb” claimed to have produced, in his immensely influential Hamārī shā‘irī (1926-27), the first defense of the ghazal against such attacks. His method, however, was not to take issue with the criticism but to begin by accepting it, and then to “complete” the picture by adding “what had been left out”; where critics had presented “one side of the picture,” he would supplement their work by showing “the other side,” so that both sides taken together would enable people to form an accurate opinion about the poetry (15-16). On Adīb’s approach, see Shamsur Raḥmān Fārūqī, “Hamārī shā‘irī par ek naz̤ar-e ṡānī,” in Tanqīdī afkār (Allahabad: Urdu Writers Guild, 1984), 159-89.

6. See, for example, ‘Alī Sardār Ja‘frī, Paiġhambarān-e suḳhan: Mīr, Ġhālib, Kabīr, 2d ed. (Bombay: Adshot Publications, 1987 [1970]), which adopts the credo that “poetry is a part of prophecy.” The author is very clear about his political intentions: “For modern political and revolutionary movements to become stronger, they must be joined in a relationship with medieval revolutionary thought”—which is to be derived from classical poetry (6).

7. Fārūqī, Shi‘r-e shor angez, 3:42, 62. The point is discussed at length on pp. 61-62 and 75.

8. Because these two names constantly recur, they will be used in the text from now on without diacritics.

9. Āzād, āb-e Ḥayāt (Water of life), 14. Page references to this work will hereafter appear in the text.

One. A Garden Now Destroyed

So there is now no hope at all of another such

master of poetry being born in India.

For he was the nightingale of a garden

that has been destroyed.

1. The Lost World

By the late eighteenth century, the once-mighty Mughal Empire was in rapid political decline. The magnificent Red Fort itself had been sacked over and over by a series of plunderers: first by Nādir Shāh and his Persians (1739), who carried off the famous Peacock Throne; then by Aḥmad Shāh Abdālī and his Afghans (1757); and finally by Ġhulām Qādir and his Rohillas (1788), who not only despoiled the library but even dug up the palace floors looking for concealed valuables. Toward the end of this period the unfortunate emperor Shāh ‘ālam II (r. 1759-1806), Aurangzeb’s great-great-grandson, had much to endure. He was crowned while a fugitive in Bihar, and did not even manage to return to Delhi until 1772. His political impotence became proverbial; as the saying went, “The realm of Shāh ‘ālam—from Delhi to Palam.”[1] The emperor knew humiliation, helplessness, and actual poverty. He was “only a chessboard king” (253).

At length he accepted the Marathas as his protectors, and from 1785 to 1803 they were the real power behind his throne. Even then, though, his tribulations were not over. For when the brutal Ġhulām Qādir seized the city in 1788, he was outraged at finding so small an amount of loot—and had Shāh ‘ālam blinded. The Marathas later came to the rescue, retook the city, and restored the blind emperor to his nominal throne. But gradually, amidst the military and political turbulence of the period, the British gained the upper hand over the Marathas; finally, in 1803, Lord Lake took Delhi. For the first time in decades, stability returned to the city. The new conquerors, like the old, valued the Mughal dynasty for its time-honored legitimating power, its continuing hold on the Indian imagination. The British kept Shāh ‘ālam II on the throne until his death three years later, at the age of seventy-nine.[2]

Despite Shāh ‘ālam’s legal sovereignty, his throne rested uncertainly on layers of nostalgia and remembered glory. He himself as an “emperor” was hopelessly vulnerable. But he had another calling as well: he was a serious poet, as well as a notable connoisseur and patron of poetry. Toward the end of his life, poetry became his chief pursuit. And as a poet, he could feel an unchallengeable pride and confidence. He came from a tradition that knew itself as the center of its cultural world—and knew that its cultural world was the only one that counted. For he wrote in the beautiful court language, Persian, and took full advantage of its rich classical literature and its sophisticated, highly developed array of genres. As Persian poets had done for centuries, he often composed in the brief, intense lyric genre of ghazal (Ġhazal), with its endless romantic and mystical possibilities. And as Persian poets had also done for centuries, he chose a personal pen name (taḳhalluṣ), which he incorporated into the last verse of each ghazal: he called himself “āftāb” (Sun).

Moreover, as North Indian poets had been doing since at least the beginning of the eighteenth century, he composed ghazals not only in Persian, but also in Urdu. Urdu, while still resting firmly on its Indic grammatical and lexical base, was steadily enlarging its repertoire of Persian genres and imagery. As a literary language, Urdu was absorbing almost everything that Indians loved in Persian—so that it was in fact gradually supplanting Persian. Thus it is not surprising that when Shāh ‘ālam II wrote in Urdu, he, like most poets, used the same pen name as he did for his Persian verse. When he composed poetry in the Indic literary language of Braj Bhasha, however, he used a different pen name: his own title “Shāh ‘ālam” (Ruler of the World). He was also fluent in Panjabi, and is said to have known Arabic, Sanskrit, and Turkish. During his reign “the Red Fort once again became a center of literary enthusiasm.”[3] It was the scene of frequent mushairahs (mushā‘irah), or poetry recitation sessions.

Shāh ‘ālam’s eldest son, Javān Baḳht, shared his love for poetry. “This exalted prince was so inclined toward poetry that he arranged for mushairahs to be held twice a month in his apartments; he used to send his own mace-bearer to escort the distinguished poets on the day of the mushairah, and encouraged everyone by showing the greatest kindness and favor.”[4] Javān Baḳht, however, died young. When Shāh ‘ālam himself died, the British installed his second son on the throne as Akbar Shāh II (r. 1806-1837). Akbar Shāh composed poetry only casually, because it was the thing to do; playing on his father’s pen name, he called himself “Shu‘ā” (Ray). But the new heir apparent, Akbar Shāh’s son Bahādur Shāh (1775-1862), vigorously sustained the family poetic tradition: he brought poets into the Red Fort, held mushairahs, and pursued his own strong literary interests.[5]

Bahādur Shāh was a very serious poet. The famous pen name he chose for himself, “Z̤afar” (Victory), was actually part of his given name, Abū Z̤afar Sirāj ud-Dīn Muḥammad Bahādur Shāh. His mother, Lāl Bā’ī, was a Hindu. Bahādur Shāh had been educated entirely within the Red Fort, under his grandfather’s supervision, and had mastered not only Urdu and Persian but Braj Bhasha and Panjabi as well; he composed a volume (dīvān) of poetry in each of these four languages. Like his grandfather, he used two separate pen names: “Z̤afar” for poetry in Urdu and Persian, “Shauq Rang” (Passionate) for the rest of his verse.[6]

When Akbar Shāh II died, Bahādur Shāh, who was sixty-two years old at the time, duly replaced him on the throne—a throne behind which the British were definitely the real power. The new emperor Bahādur Shāh II (r. 1837-1857) was a man of parts: he studied not only poetry but mystical philosophy as well, and practiced calligraphy, pigeon flying, swordsmanship, horse breeding, riding, and other aristocratic arts. While his dress and most of his tastes were simple and dignified, he enjoyed the company of women: he was much influenced by his favorite wives, and continued to marry an occasional new one even into his sixties and seventies. Living on a fixed British pension, he nevertheless had royal traditions of largesse to uphold, as well as many relatives and dependents to support, so that he was hard-pressed for funds; he used every possible means to increase his income, and his financial affairs were always in disarray.[7] He certainly felt the difficulty of his position—and sometimes wittily used it as a source of poetic imagery. As he wrote in one of his poems, “Whoever enters this gloomy palace/Is a prisoner for life in European captivity.”[8]

Bahādur Shāh was a man of “cultured and upright character,” who as a “philosophic prince” could have “adorned any court,” and whose “interests and tastes were primarily literary and aesthetic.” The British certainly viewed him with less and less respect over time; yet, as Percival Spear argues, a large part of their disdain was a function of their own increasingly limited, utilitarian outlook on life. The emperor was “a poet, and so could expect no more consideration than the same men gave to Shelley or Byron or Keats.” But since the emperor was so much loved and esteemed in India, motives of prudence kept British disdain in check.[9] Even when the physical power of the Mughal emperor was close to nonexistent, his symbolic power as a cultural icon was a force to be reckoned with. As the governor general put it in 1819, the British should seek to avoid any behavior that “might be misinterpreted into a wanton oppression of a dignified tho’ unfortunate Family.”[10]

Even as the emperor’s royal prerogatives slowly eroded, the decline was managed for the most part with decorum: the hostile British Resident Hawkins, who made a point of violating court etiquette, was soon sent home. “After this, in the deft hands of William Fraser and then Thomas Metcalfe, even the gradual withdrawal of British recognition of the imperial status was smoothed by dignified deference.”[11] C. F. Andrews makes a similar point: although “real power passed more and more, every year, into the hands of the English,” nevertheless since “the English were, throughout this whole period, very few in numbers,” and since they “did not interfere more than they could possibly help,” the result was a kind of “dual control” that was “not altogether disturbing.”[12] Peter Hardy notes that in studying the period “one is impressed by how little in feeling and in style of life the educated classes of upper India were touched by the British presence before 1857.”[13] As Azad later put it, “Those were the days when if a European was seen in Delhi, people considered him an extraordinary sample of God’s handiwork, and pointed him out to each other: ‘Look, there goes a European!’ ”[14]

Narayani Gupta describes a lively Hindu-Muslim cultural life—conducted entirely in Urdu, by people who had consciously chosen not to learn English. The father of the great Urdu novelist Nażīr Aḥmad (1836-1912) went so far as to tell the boy he would rather see him dead than learning English. As the recently founded (1825) Delhi College developed, not its English section but its Urdu-medium “Oriental” one flourished—and showed itself especially zealous in pursuing the new Western sciences.[15]

Spear characterizes this period, especially the second quarter of the nineteenth century when the “English Peace” was well established, as a time of prosperity, confidence, urban growth, and religious and cultural harmony. “The Court was the cultural centre, the Hindus dominated the commercial life and the British conducted the administration”; daily life was a matter of mutual accommodation and shared festivals, with “much interchange of civilities and much give and take.” Spear paints an almost (though not quite) idyllic picture: “Old and new for a time met together in the short-lived Delhi Renaissance.”[16] C. F. Andrews agrees: the “impact from the West” in fact “led to a cultural renaissance which proceeded remarkably from within.”[17] This Delhi Renaissance was rich in the arts, and extraordinarily influential. Lucknow, untouched by the kind of repeated plundering that Delhi had endured, was a great magnet and center of patronage; but Delhi, as the last Mughal capital, had a special nostalgic appeal. The court was “the school of manners for India” and “a cultural influence of great value”; its prestige and patronage made it “the natural centre of all the arts and crafts.”[18] Urdu poetry was widely and seriously cultivated: there were not only frequent mushairahs at the Red Fort, but also weekly ones held on the Delhi College premises,[19] as well as numerous privately sponsored ones. When it came to poets, Bahādur Shāh’s circle included, besides himself, one great poet, several major ones, and literally dozens of highly competent minor poets.

| • | • | • |

The great poet, Mirzā Asadullāh Ḳhān (1797-1869), who used the pen name “Ġhālib” (Victorious), is now universally recognized as either the first or second greatest classical ghazal poet of Urdu; his reputation is rivaled only by that of Mīr Taqī “Mīr” (c. 1722-1810). Ġhālib came of Turkish stock, and was always proud of his family’s military tradition: his father had died fighting in the raja of Alwar’s army, while his uncle Naṣrullāh Beg had been in the service of the Marathas and then in 1803, when the British took Delhi, had become a commander under Lord Lake. The British pension inherited on this uncle’s death was the mainstay of Ġhālib’s finances throughout most of his life. He was raised in Agra by his mother’s well-off and aristocratic family. At the age of eleven he began writing Persian poetry; he had already, according to his own account, been writing in Urdu for some time. When he was thirteen he was married—by family arrangement, as was customary—to a girl from a wealthy and socially elite background; a year or two later he settled in Delhi, which became his home for the rest of his life.[20]

Ġhālib’s life in Delhi was firmly grounded in the aristocratic Persianized culture surrounding the court. He always knew who he was, and knew his own worth as a poet; despite his lifelong financial and personal vicissitudes, neither his confidence nor his sense of humor ever really failed him. His complex, metaphysical, “difficult” poetry, however disturbing to conventional tastes, was arresting and undeniably powerful; even during his lifetime he began, so to speak, to be Ġhālib.

But he also had many friends in the British administration, including the Resident John Fraser. He made a two-year journey to Calcutta and took a strong interest in the English influence on view there—including newspapers, as yet unknown in Delhi. (Although he knew neither English nor Bengali, Persian served as an effective link language.) And he certainly thought the Emperor Akbar’s administrative style inferior to that of the English, as he made clear on one occasion to the great reformer Sir Sayyid Aḥmad Ḳhān (1817-1898).[21]

Ġhālib met the new culture on his own terms and tried throughout his life to make it behave like the old. In some respects, of course, it obliged him. The elaborate etiquette of English ceremonial gatherings was directly borrowed from that of the Mughal court, and Ġhālib set considerable store by it: “In the Government durbars I occupy the tenth place to the right, and the marks of honour prescribed for me comprise a ceremonial robe, seven gifts of cloth, a turban with an embroidered velvet band and jewelled gold ornament to wear in it, a string of pearls and a cloak.”[22] Such feudal honors were as consciously manipulated by the English as they had always been by the Mughals.[23]

Ġhālib tried to extend his aristocratic status into more modern realms as well. In 1842 he was invited to be interviewed for the newly created post of Persian professor at Delhi College. A famous anecdote gives a vivid picture of Ġhālib’s arrival, in his palanquin, for the interview. He alighted, but refused to enter the building until Mr. Thomason, the secretary, appeared and gave him the formal welcome to which his aristocratic rank entitled him. Time passed. Finally, Mr. Thomason came out to try to resolve the situation:

Despite his poverty and indebtedness, Ġhālib made the grand gesture with a flourish. Honor was honor, it was clear where it lay, and that was the end of the matter.[Mr. Thomason] came out personally and explained that a formal welcome was appropriate when he attended the Governor’s durbar, but not in the present case, when he came as a candidate for employment. Ghalib replied, “I contemplated taking a government appointment in the expectation that this would bring me greater honours than I now receive, not a reduction in those already accorded me.” The Secretary replied, “I am bound by regulations.” “Then I hope that you will excuse me,” Ghalib said, and came away.[24]

Ġhālib tried again and again to teach the new regime manners, especially when it came to the vital question of patronage. He reminded the English that poetry was a uniquely potent art, conferring immortal fame not only on its creators, but also on the patrons whose generosity it celebrated. In 1856 he composed a Persian ode (qaṣīdah) to Queen Victoria, and forwarded it to London through Lord Ellenborough. But he then received a bureaucratic letter suggesting “that the petitioner, in respect to the norms of administrative procedure, should channel his petition through the administrator in India.” He therefore sent his ode again, through the proper channels, along with a letter in which he politely reminded the queen of the well-known and long-established duty that sovereigns owed to poets. (It was indeed a long-established one: more than five centuries earlier, the Indo-Persian poet Amīr “Ḳhusrau” (1253-1325) had used exactly the same line of argument on one of his own patrons.)[25] Ġhālib pointed out to Queen Victoria that since great kings had customarily “rewarded their poets and well-wishers by filling their mouths with pearls, weighing them in gold and granting them villages and recompense, the exalted queen should bestow upon Ghalib, the petitioner, the title of Mihr-Khwan, and present him with the robe of honour and a few crumbs from her bounteous table—that is, in English, a ‘pension.’ ” He was eagerly awaiting a response—but by then it was 1857.[26]

| • | • | • |

The natural source of patronage for Ġhālib would have been the Red Fort. Poets were so much a part of Persianized court life that they often became intimate “boon companions” to the king; in some cases they became “part of the royal paraphernalia” and changed hands along with the throne.[27] Ġhālib indeed found some support from the court, though never what he needed and felt he deserved. In 1850 he wrote to Bahādur Shāh:

The absolute, passionate confidence of Ġhālib’s claim has no bombast in it. He speaks with the impatient certainty of one who knows beyond doubt both what his craft is worth, and what he is worth as a master craftsman.I swear that you too must feel pride in the great kindness of fortune, that you possess a slave like Ghalib, whose song has all the power of fire. Turn your attention to me as my skill demands, and you will treasure me as the apple of your eye and open your heart for me to enter in.…And why talk of the poets of the Emperor Akbar’s day? My presence bears witness that your age excels his.[28]

But although Ġhālib had many admirers and shagirds (shāgird), pupils who studied poetry under his guidance, Bahādur Shāh Z̤afar was not inclined to be one of them. Like any other serious poet, Z̤afar made his own choice of a master or ustad (ustād), who would criticize and correct his verses; apprenticeship was, in poetry as in other arts and crafts, the accepted way to acquire a skill. Z̤afar’s first ustad was Shāh Naṣīr ud-Din “Naṣīr” (Helper) (d. 1838), who was more or less Z̤afar’s contemporary and an important poet in his own right. At the middle and end of every month Shāh Naṣīr sponsored mushairahs, some of which were notorious for the complicated meter and rhyme patterns (t̤araḥ) assigned to be used in the poems recited. Around 1803, however, Shāh Naṣīr left Delhi for the Deccan. Z̤afar then briefly named as his ustad ‘Izzatullāh “‘Ishq” (Love); and after him Mīr Kāz̤im Ḥusain “Beqarār” (Restless), a shagird of Shāh Naṣīr; Beqarār eventually resigned to become Lord Elphinstone’s chief secretary. Z̤afar’s true ustad was Beqarār’s replacement, the major poet Shaiḳh Ibrāhīm “Żauq” (Taste) (c. 1788-1854), who had also been a shagird of Shāh Naṣīr. Żauq and Z̤afar developed such a satisfactory relationship that it remained firm for four decades.[29] Ġhālib, by contrast, received only a minor token of royal favor: he was commissioned to compose, in Persian, a Mughal dynastic history—a task he found tedious and uninspiring.[30]

Only when Żauq died in 1854 did Z̤afar finally appoint Ġhālib, the obvious choice, to fill the prestigious post of royal ustad. Z̤afar seems to have done this somewhat grudgingly, and Ġhālib accepted only because he needed the pension that went with the job.[31] Though he was proud of his position at court—“The Emperor loved me like one of his sons”—Ġhālib complained that the pension was “tiny.”[32]

While we know a great deal from many sources about the lives of major figures like Żauq and Ġhālib, we know relatively little about their hundreds of less famous contemporaries. Most of our information about minor poets comes from the tazkirahs (tażkirah), traditional anthologies of poetry. One especially interesting and comprehensive tazkirah, The Garden of Poetry (1855) by Mirzā Qādir Baḳhsh “Ṣābir” (Patient),[33] lists among its 540 contemporary poets no fewer than fifty princes related to Z̤afar. Such royal relatives were usually dilettantes rather than serious poets; their sheer numbers show how socially correct it was in their world to affect literary tastes. An interest in Urdu language and literature had even come to be considered a hallmark of the city itself: “Anyone who had not lived in Delhi could never be considered a real knower of Urdu, as if the steps of the Jāma‘ Masjid were a school of language,” as Maulvī ‘Abd ul-Ḥaq put it. In Delhi poetry “was discussed in every house,” for “the emperor himself was a poet and a connoisseur of poetry” and “the language of the Exalted Fort was the essence of refinement.”[34]

The Garden of Poetry includes fifty-three Delhi poets who seem fromtheir names to be Hindus (mostly Kayasths and Kashmiri Brahmans)and describes a scattering of poets from unexpected walks of life: “Pairā”(Adorner), a poor water-seller in Chandni Chauk; “Sharīr” (Naughty), a merchant in Panjabi Katra; “Zirġhām” (Lion), a young wrestler; “Z̤arāfat” (Wit), a lady with a colorful past who had now settled into respectability; “Banno” (Girl), a courtesan, who had caught the taste for poetry from her lover, one Gulāb Singh; “Faṣṣād” (Cupper), a barber who was inspired by the company of Shāh Naṣīr; “Farāso,” a Western protégé of Begam Samrū; and others.[35]

Ṣābir treated the poet Z̤afar, however, as a special case, for he was also the Emperor Bahādur Shāh, “refuge of both worlds, for whom angels do battle, ruler of time and space, lord of crown and seal…at whose command which is the twin of Fate, the revolution of the sky is established.” His literary powers were equally exalted: “Maẓmūns [themes][36] of submission in his poetry are equal in rank to pride and coquetry,” and “the radiance of meaning [ma‘nī] is manifest through his words.” For when it comes to poetry, not only words but even the very letters that embody them on paper are magically potent:

In short, the emperor’s poetry deserves praise so endless that if “the messenger of Thought” ran for a thousand years, it would still only cover as much distance as “the footprint of a weak ant” by comparison. For, as Ṣābir puns, “from the East/opening verse (mat̤la‘) to the West/closing verse (maqt̤a‘) is the excursion ground of that Sun whose domes are the skies.”[37] In principle, the emperor was still the center of the universe, just as his ancestors, with their vast domains and absolute powers, had always been.The sequences of lines, through the reflection of maẓmūns, are lamp-wicks for the bedchamber of the page. The circular letters, through the effect of meaning (ma‘nī), are the wine-mark on the flagon in the festive gathering of pages. The colorfulness of festive meaning is the glistening of wine; in martial verses, the wetness of the ink is blood and perspiration. In mystical verses, the circular letters are seeing eyes; and in romantic verses, tear-shedding eyes. And in spring-related verses, [the decorations] between the lines are flowerbeds; and in sky-related verses, the Milky Way. The breath, through the floweringness of the words, is the garden breeze; and vision, through the freshness of the writing, is the vein of the jasmine. The line (miṣra‘) has the stature of a cypress; the verse is the eyebrow of the beautiful ones of Khallukh and Naushad.

| • | • | • |

Not surprisingly, literary people flocked to the court of such an impressive poet-emperor, seeking both learning and patronage. During the period of the Delhi Renaissance two remarkable young men studied in Delhi: Muḥammad Ḥusain, who chose for himself the pen name “Āzād” (Free), and Alt̤āf Ḥusain, who first called himself “Ḳhastah” (Worn Out) but later changed his pen name, very possibly at Ġhālib’s suggestion, to “Ḥālī” (Contemporary). The power that these two came to exercise over Urdu literature and criticism has been unequaled ever since.

Muḥammad Ḥusain Azad was the older of the two. He was born in Delhi, in 1830; his mother Amānī Begam, who came from a Persian émigré family, died when he was only three or four years old. His father, Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir (c. 1810-1857), who also came from a family of learned Persian émigrés, was a man of versatile talents and played a significant role in the cultural life of his day. Educated at the newly founded Delhi College, Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir stayed on for a time as a teacher; but he found the salary too low. He then for many years held a series of administrative positions on the collector’s staff, while also erecting a market for foreign merchants, a mosque, and a Shī‘a religious hall (imāmbāṛah) in which he himself sometimes preached. In addition, he involved himself in prolonged and acrimonious Shī‘ite religious controversies.

And as if all this were not enough, he also bought a lithograph press, and in early 1837 launched the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār (Delhi Urdu Newspaper), probably the first Urdu newspaper in North India.[38] The Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār had, like almost all newspapers of the period, an extremely limited circulation (69 subscribers in 1844, 79 in 1848). It followed a dexterously balanced political line. In a general way it was solidly pro-British, but particular instances of official injustice, corruption, or other wrongdoing came in for criticism. And although it reported—and deplored—many cases of flagrant misgovernment by Indian rulers, including Bahādur Shāh, these were almost always ascribed to the machinations of (evil) courtiers who pulled the wool over a (good) king’s eyes.[39]

Around 1845 Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir enrolled his only son in Delhi College. Muḥammad Ḥusain did well there. He was enrolled in the Urdu-medium “Oriental” section, which offered Arabic and Persian rather than English. In both 1848 and 1849 his Urdu essays won prizes; these essays, as his teachers noted, showed the good effects of his family background in newspaper work.[40] At some point during these years his family arranged his marriage to āĠhā’ī Begam, the daughter of another Persian émigré family. After completing Delhi College’s eight-year curriculum, Muḥammad Ḥusain graduated, probably in 1854. He had started to assist his father in his newspaper work, and in the 1850s his name appears as “printer and publisher” of books produced by the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār Press. He continued with this work until 1857.[41]

Muḥammad Ḥusain Azad later claimed that throughout his childhood and youth he had spent a great deal of time with the poet Żauq, the royal ustad, who was a close friend of his father’s. He claimed Żauq as his own ustad—although at this early stage in his life Azad went to few mushairahs and wrote almost no poetry. He claimed to have been especially intimate with Żauq, and to have received many confidences from him. It seems probable that he had a considerable amount of contact with Żauq, but we have only his word for the nature and intensity of their relationship. His most painstaking and fair-minded biographer, Aslam Farruḳhī, speaks of his “Żauq worship.”[42] Azad certainly exaggerated at times: he claimed, for example, to have sat constantly at Żauq’s feet, absorbing both “outer” and “inner” (that is, mystical) wisdom, for “twenty years.”[43] Azad made even more extravagant assertions as well. He claimed that under Żauq’s direction he had read, and made abridgements from, no fewer than 350 volumes of the work of classical poets; later the figure somehow became 750! These claims are quite impossible to accept, though they certainly show the kind of classical literary study Azad most admired.[44]

Żauq’s death in 1854 must have been a heavy blow. But Azad eventually undertook a project that offered consolation: the editing of Żauq’s ghazals for publication. He planned to do this task slowly, carefully, and lovingly. Moreover, he pursued his own literary work. He took Ḥakīm āĠhā Jān “‘Aish” (Luxury) as his new ustad, in a working relationship that continued until 1857. Azad’s first known poem, a nineteen-verse “continuous ghazal” (Ġhazal-e musalsal), was published in the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār. The poem was a meditation on the fleetingness and untrustworthiness of life, and it was called “A History of Instructive Reversals.” It was published, with excellent timing, on May 24, 1857.[45]

| • | • | • |

Alt̤āf Ḥusain Hali, born in 1837, was seven years younger than Azad; he came from an old family in the famous town of Panipat, north of Delhi.[46] Although he was orphaned at the age of nine, he had an affectionate older brother (an inspector of police, who also wrote Persian poetry) and two older sisters who looked after him. He was a bright and promising child, tremendously eager to learn, and was given a traditional basic education. His first teacher was a Ḥāfiz̤, someone who had memorized the whole Quran; Panipat was “famous for the number of its Hafizes,”[47] and Hali too achieved this formidable feat. Then he began to learn Persian; along with the language, he studied the history, literature, and especially poetry of Iran—but he always described these studies as “elementary.” As he grew older, he himself took the initiative in arranging for an Arabic teacher, but his lessons ended before he had a chance to make as much progress as he wished. He was left unsatisfied: “Although the spontaneous passion for learning in my heart was unbounded, I never had the chance for a regular and continuing education.”[48] What he longed for was the classical Persian and Arabic training of a traditional Indo-Muslim scholar.

His brother and sisters, however, had other plans for him. When he was seventeen years old, they arranged his marriage to a cousin, Islām un-Nisā, and thus inducted him into the ranks of adulthood. They then pressured him to find work and augment the family income, which was none too large. The young Alt̤āf Ḥusain was a dutiful boy, and everyone in the family made sure he saw his duty clearly. Alt̤āf Ḥusain’s scholarly aspirations were obviously destined to wither on the vine. Given the circumstances, the time and place and culture in which he lived, this was a foregone conclusion.

Alt̤āf Ḥusain, however, then did the only truly astonishing, defiant, flagrant deed in his long, sober, impeccable life. He waited for a night when his new bride was at her parents’ house—and he slipped away. He was not yet eighteen, and had never been anywhere. Yet without hesitation he simply ran away from home. Hali himself, years later, gave his own account of this event: his relatives had “forced” him to marry, and unfortunately this “yoke that was placed upon my shoulders” meant that “apparently now the doors of education were closed on every side.” He took flight, and never apologized for it: “Everyone wanted me to look for a job, but my passion for learning prevailed.” Besides, he added in extenuation, “my wife’s family was comfortably off.”[49]

Penniless, traveling alone for greater anonymity, he set out to walk the fifty-three miles to Delhi. Even after he arrived, he was sometimes homeless, and so often hungry that his health was affected. But he was able to slake his thirst for knowledge. In later years, far from having regrets, he looked back nostalgically on this time: “I saw with my own eyes this last brilliant glow of Delhi, the thought of which makes my heart crack with regret.”[50]

In Delhi, he studied Arabic language and literature, including poetry and meter, at a flourishing, “very spacious and beautiful” traditional school (madrasah), the Madrasah of Ḥusain Baḳhsh.[51] Many years later he described his cultural background at the time.

Hali regretted that during his year and a half in Delhi he hadn’t even gone to look at Delhi College, and had never chanced to meet his distinguished contemporaries who were being educated there. He named three in particular: the great teacher and translator Maulvī Żakā’ullāh (1836-1907?), the famous novelist Nażīr Aḥmad, and Muḥammad Ḥusain Azad.[52]Although the old Delhi College was then in all its glory, I’d been brought up in a society that believed that learning was based only on knowledge of Arabic and Persian. Especially in the Panipat area, first of all nobody even thought about English education, and if people had any opinion about it at all it was as a means of getting a government job, not of acquiring any kind of knowledge. On the contrary, in fact: our religious teachers called the English schools barbarous. When I arrived in Delhi, at the school in which I had to live night and day, all the teachers and students considered graduates of the college nothing but barbarians.

If he failed to meet his peers, he lost no time in seeking out the greatest of his elders: he often went to visit Ġhālib, and persuaded him to explain difficult passages in his Urdu and Persian poetry. Treating Ġhālib as an ustad, he showed him his own earliest ghazals. Ġhālib is said to have duly given him iṣlāḤ, “correction,” as an ustad should, and to have encouraged him to persist with his writing. Unfortunately, none of this early poetry—written under the pen name of “Ḳhastah”—has survived.

Hali lay low so successfully that for a year and a half his family had no idea at all where he was, or even whether he was alive or dead. There is no evidence that he would ever have voluntarily returned to them. But in 1855 they learned of his whereabouts, recaptured him, “compelled” him “forcibly, willy-nilly” (as he put it) to leave Delhi, and took him back to Panipat. He had the nerve to run away, but not the nerve to look his elders in the eye and defy them. So ended the great period of his education.

By 1856 Hali had an infant son, and he himself had recognized—or had been forced by family pressure to recognize—the need to find a job. He went alone to Hissar, without connections or references, and managed to get a position in the deputy collector’s office. The salary was small, but at least it would be steady. Hali did his work most conscientiously, and rapidly mastered the office routines. But by then it was 1857.[53]

| • | • | • |

1857—the end of this particular world. An upheaval like an earthquake, opening a chasm so deep that no one could see to the bottom. It was the end of the court, and thus a profound “break in cultural as well as political tradition.”[54] As Andrews puts it, “The renaissance at Delhi gave a sudden illumination to the age.…Light flickered and leapt up for a brief moment before it died away.” But the light did not die of its own accord—Andrews is very clear about that. The light was killed. “More than any other single cause, the Mutiny killed it.”[55]

Notes

1. Palam, now the site of the Indira Gandhi International Airport, is on the outskirts of Delhi.

2. Percival Spear, The Oxford History of Modern India, 1740-1947 (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1965), 37-43; Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 60.

3. Parvez, Bahādur Shāh Z̤afar, 272; see also 32, 344. Examples of āftāb’s Urdu ghazals appear on pp. 272 and 343.

4. Lut̤f, Gulshan-e hind, 72.

5. Parvez, Bahādur Shāh Z̤afar, 38, 276.

6. Ibid., 38, 344.

7. Ibid., 234-37, 75-76, 60-74.

8. Na‘im Aḥmad, ed., Shahr āshob (Delhi: Maktabah Jāmi‘ah, 1968), 196. The word firang, used for Europeans, is a rendering of “Frank,” and qaid-e firang, “Frankish captivity,” was considered to be an especially harsh form of imprisonment. If given a mystical reading, the verse would refer to the wretched fate of everyone born into the world.

9. Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 72-73, 30.

10. Fisher, A Clash of Cultures, 146.

11. Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 78.

12. Andrews, Zaka Ullah of Delhi, 26-27.

13. Peter Hardy, “Ghalib and the British,” in Ghalib: The Poet and His Age, ed. Ralph Russell, 55.

14. Āzād, ed., Dīvān-e Żauq, 145.

15. Gupta, Delhi between Two Empires, 5-8.

16. Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 194-200.

17. Andrews, Zaka Ullah of Delhi, 10. Sadiq (Azad, 2) also accepts the term renaissance for this period. Maulvī ‘Abd ul-Ḥaq (quoted in Farruḳhī, Āzād, 1:43-44) presents a similar picture.

18. Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 82-83.

19. Gupta, Delhi between Two Empires, 5.

20. Russell and Islam, Ghalib, 23-27.

21. Ibid., 52-54, 49, 90-91.

22. Ibid., 219.

23. On the forms of this manipulation, see Bernard S. Cohn, “Cloth, Clothes, and Colonialism: India in the Nineteenth Century,” in Cloth and Human Experience, ed. A. B. Weiner and J. Schneider (New York: Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, 1989), 303-53.

24. Russell and Islam, Ghalib, 63. This anecdote is first told by Azad (487-88), and then repeated with minor changes by Hali in Yādgār-e Ġhālib, 28-29. Russell and Islam rely on Hali’s version.

25. Like Ġhālib, Ḳhusrau listed a number of anecdotes about lavish royal generosity to poets, and emphasized the eternal fame that only poets can provide. See Mirza, Life and Works of Amir Khusrau, 108-12.

26. Ghalib, Dastanbuy, 48.

27. On the poet’s role as nadīm, see Meisami, Persian Court Poetry, 6-11. Amīr Ḳhusrau (Life and Works of Amir Khusrau, 45, 78) used nadīmī to describe his own relationship with at least one patron.

28. Quoted in Russell and Islam, Ghalib, 73-74.

29. Parvez, Bahādur Shāh Z̤afar, 273, 278-85.

30. Russell and Islam, Ghalib, 71-75.

31. Ibid., 84.

32. Ġhālib, Ḳhut̤ūt̤, 1:373-74.

33. It has been argued that the actual author of this tazkirah was the poet Imām Baḳhsh “Sahbā’ī.” For my purposes, the identity of the author is not important.

34. ‘Abd ul-Ḥaq, Marḥūm Dihlī Kālij, 12-13.

35. Ṣābir, Gulistān-e suḳhan, 157-58, 166, 286, 337, 344-45, 390, 385. On “Farāso,” see Husain, Bahadur Shah II, xli.

36. “Themes” is an umbrella term, a convenient starting point, but maẓmūn is difficult to translate with precision and will be discussed at length in chap. 7.

37. Ṣābir, Gulistān-e suḳhan, 345-46.

38. Imdād Ṣābrī, Urdū ke aḳhbār navīs (Delhi: Ṣābrī Academy, 1973), 1: 146-48; Sadiq, Azad, 3-8. Until late 1843 the editor of record of the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār was in fact Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir’s father, Maulvī Muḥammad Akbar. The Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār was probably the second Urdu newspaper in India: the first, a Persian-Urdu combination, had been started in Calcutta in 1822. But another was also started in 1837, and exact dates are hard to determine. For a detailed account of the available evidence, see Khan, A History of Urdu Journalism, 25-30, 65-73, 209-10.

39. Khan, A History of Urdu Journalism, 74-83. See also Ḳhvājah Aḥmad Fārūqī, ed., Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār (Delhi: Shu‘bah-e Urdū, Delhi University, 1972), which reproduces selections from the paper for the year 1840.

40. ‘Abd ul-Ḥaq, Marḥūm Dihlī Kālij, 45-46.

41. Farruḳhī, Āzād, 1:80-82, 111; Khan, A History of Urdu Journalism, 71.

42. Farruḳhī, Āzād, 1:93.

43. Āzād, Dīvān-e Żauq, 2; Farruḳhī, Āzād, 1:88.

44. For a discussion and refutation of these claims, see “‘ābid” Peshāvarī, Żauq, 69-70. See also Farruḳhī, Āzād, 2:284-85.

45. Farruḳhī, Āzād, 1:94-98. The Urdu title of the poem was “Tārīḳh-einqilāb-e ‘ibrat afzā.”

46. Some of Panipat’s historical and religious associations are discussed in Steele, “Hali and his Muqaddamah,” 2.

47. Leitner, History of Indigenous Education, part 2, 14.

48. Ḥālī, Kulliyāt-e naṡr, 1:334.

49. Ibid.

50. Shujā‘at ‘Alī Sandīlvī, Ḥālī, 19.

51. Leitner, History of Indigenous Education, part 2, 2.

52. Ḥālī, Kulliyāt-e naṡr, 1:335.

53. Ibid., 1:335-36.

54. Spear, Twilight of the Mughuls, 83.

55. Andrews, Zaka Ullah of Delhi, 66.

2. Beyond a Sea of Blood

The story of 1857 has been told and retold, from numerous points of view. It indeed began as a mutiny, and the “Mutiny” it has remained in the British historical imagination. It soon spread beyond the army, however, and thus became much more than a mutiny; South Asian historians often describe it as the “First War of National Independence.” For our present purposes we can call it the Rebellion.[1] By whatever name, it had profound effects on the lives of virtually all urban North Indians.

Bahādur Shāh “Z̤afar,” poet-emperor and English pensioner, was utterly undone by the events of 1857. On the one hand, it has been argued that he was an ardent participant in the Rebellion—that he had been secretly informed about it in advance, that he tried energetically to take charge of it and give it an inclusive, nationalistic character.[2] It has also been argued that although the Rebellion took him by surprise, at the crucial moment the “Imperial yearnings in his heart” suddenly awoke, and he “entered into the full spirit” of the rebels, for “rather than continue in slavery, it would be preferable even to die.”[3] On the other hand, he has also been blamed for the collapse of the Rebellion: he failed to rise to this “great occasion” and uphold the kingship, so that although the common people participated in the Rebellion, “the elite remained prey to vacillation,” and “the English had the chance to destroy Delhi.”[4]

No doubt the prospect of wielding in practice the power he had always claimed in theory was alluring. But Bahādur Shāh was eighty-two years old, and was never able to control the rebels—or even to restrain his own headstrong sons from atrocities like the killing of captured English women and children. He was almost certainly taken by surprise on May 11, when the first rebel soldiers arrived from Meerut and appeared beneath his balcony; he clearly disapproved of their ill-bred, unmannerly behavior. Once they seized the city and claimed him as their emperor, however, he displayed considerable activity on behalf of their cause. He became, in Spear’s words, “a contingently willing accessory after the fact.”[5]

For he tried to restore order in the city, maintain communal harmony, raise and allocate revenues, and inspire the troops to fight the English instead of despoiling the citizens.[6] His power was far from absolute, but it was also far from nonexistent. May 17: “The King summoned many of the Sepoys to his presence and spoke to them very severely.” June 17: “The King sent for the chief of the mutineers, and threatened to take poison unless greater discipline were enforced and the oppressions discontinued. The chief promised immediate compliance.” July 2: “The King said it was no use his giving orders, as they were never obeyed, and he had no one to enforce them, but his decree was that the English should be caused not to exist.” August 4: “ ‘We have here 60,000 men in the city, but they have not been able to win a clod of dirt from the English.’ ” August 22: “ ‘If the Sepoys would only leave the city, and employ themselves in collecting the revenue, I should be in a position to pay them, and to protect the lives and property of the citizens.’ ”[7] His exasperated tone is not that of an absolute ruler, but neither is it that of a helpless, fearful victim.

The emperor’s leverage lay in the fact that the rebels could not afford to lose his services as their symbolic source of authority. Thus his frequent threats to withdraw his cooperation: to hold no more public audiences, to renounce the throne, to retire to some holy place, to “swallow a diamond” and die.[8] Such threats were noted with pathos and hope in the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār:

At other times, however, Bahādur Shāh made strongly anti-British remarks, and even composed martial verses that he sent to his commanding general: “May all the enemies of the Faith be killed today;/The Firinghis be destroyed, root and branch!”[10] When the British recaptured Delhi on September 18, Bahādur Shāh hesitated, then ultimately refused to accompany the rebels in their flight from the city.His Majesty has issued a proclamation wherein he has drawn attention to the fact that the majority of the powerful and influential people cause misery to the loyal subjects of the Emperor.…If the prevailing state of affairs continues, His Majesty wrote, then he would be obliged, since he had little love for worldly goods, to retire to Ajmer, to the shrine of the Khwaja.…It is heard that the above-mentioned had a great effect on the audience when it was read out.[9]

The unfortunate emperor had been placed from the start in an almost impossible position. The British, however, perceived (or chose to perceive) his court as the heart and soul of the Rebellion—and avenged themselves accordingly. They summarily executed a number of Bahādur Shāh’s sons and grandsons and other princes of the blood; still others were sentenced to life imprisonment. The Red Fort, which housed the Mughal court, had always been called the Auspicious Fort; so many of its inhabitants met dire fates that Ġhālib later renamed it the Inauspicious Fort.[11] As for the emperor himself, he was held for a time in a humiliating kind of captivity, available to be stared at by chance British visitors. Finally he was placed on trial, on ill-conceived charges of sedition. Later historians would recognize that in fact he had never formally renounced his sovereignty: while he might be a defeated enemy king, therefore, he could not properly be considered a rebel.[12] He was also charged with the death of the British women and children who had been murdered in the Red Fort.

At the trial, the prosecutor argued that “to Mussulman intrigue and Mahommedan conspiracy we may mainly attribute the dreadful calamities of the year 1857”; he sought to show “how intimately the prisoner, as the head of the Mahommedan faith in India, has been connected with the organisation of that conspiracy either as its leader or its unscrupulous accomplice.” Bahādur Shāh’s defense rested on the plea of helplessness: “All that has been done, was done by that rebellious army. I was in their power, what could I do?…I was helpless, and constrained by my fears, I did whatever they required, otherwise they would immediately have killed me.…I found myself in such a predicament that I was weary of my life.”[13] The emperor was judged guilty on all counts, exiled to Rangoon, and kept under discreet house arrest; he was by this time in a condition of vagueness and partial senility. When he died a few years later, the British buried him secretly in an unmarked grave in a wide field, which was then sown all over with grass.[14] The last surviving members of the Mughal dynasty were left in conspicuous and humiliating poverty; as Ġhālib later wrote to a friend, “The male descendants of the deposed King—such as survived the sword—draw allowances of five rupees a month. The female descendants, if old, are bawds, and if young, prostitutes.”[15]

| • | • | • |

In 1857 Ġhālib was fifty-nine years old, partially deaf, and in uncertain health. He took no significant part in the Rebellion, though it appears that he prudently “continued to maintain relations” with Bahādur Shāh by composing celebratory verse and perhaps appearing once or twice at court.[16] But he suffered much anxiety and grief, and endured financial hardship when his British pension ceased to arrive. For the most part he shut himself up in his house and began to write an elaborate history of what was happening—in ancient Persian, avoiding all Arabic words. In his history Ġhālib wrote of the disastrous effects of the revolt: one must, he said, “shed tears for the destruction of Hindustan,” which was a ruined land. “City after city lies open, without protectors.…House after house lies desolate, and the abodes of grieving men invite despoliation.”[17] Delhi College, where Azad had studied, suffered the total loss of its library. The rebels looted the Persian and Urdu books, and tore the English books into fragments that “carpeted all the college gardens to a depth of two inches.”[18] The prisons had been emptied, and the streets were in a state of anarchy; the city was full of the kind of lower-class ruffians with whom the aristocratic Ġhālib could never feel empathy. Perhaps most painful of all, the postal service had entirely broken down, so that Ġhālib—an indefatigable correspondent, writer of the most irresistible letters in Urdu literature—could no longer get news of his friends in other cities.

When the British recaptured the city in the autumn, however, things suddenly grew much worse. For several days after the assault, British troops ran wild, not only looting and plundering but also killing every able-bodied man they found. Then there followed “a more systematic reign of terror”—indiscriminate shootings, drum-head court-martials and summary hangings—that lasted for several weeks.[19] During this period Ġhālib and his family led “a prisoner’s life,” barricaded inside their house, so deprived of all news that “our ears were deaf and our eyes were blind.” When Ġhālib’s brother died after many years of insanity, the curfew was so strict that it was difficult even to bury him. “And in this trouble and perplexity, a dearth of bread and water!”[20]

Even so, Ġhālib was one of the luckier ones: his street contained some houses owned by courtiers of the loyalist maharaja of Patiala, who had arranged for special guards. He and some neighbors were eventually interrogated by a British officer. Ġhālib, ever the aristocrat, reported that the officer had “asked me my name and the others their occupation.” Ġhālib later claimed that he had established his credentials by producing the letter that acknowledged his ode to Queen Victoria. When asked why he hadn’t come over to the British camp, he replied, according to Hali’s account, “My rank required that I should have four palanquin-bearers, but all four of them ran away.” According to his own account, he described himself as “old and crippled and deaf,” unable to do anything but pray for English success. In any case, he was sent home again without harassment.[21]

Apart from a few such privileged, barricaded, and guarded neighborhoods, however, almost all the people of Delhi, and especially the Muslims, were driven out of the city. Ġhālib said there were hardly a thousand Muslims left in the whole city, while many were living “in ditches and mud huts” outside its boundaries.[22] They were still outside in December, shelterless in the cold and the winter rains. Not until early 1858 did the Hindus begin to return; the city regained something like a quarter of its former population. Mosques were occupied by troops; many beautiful old buildings had been damaged or destroyed in the fighting or were systematically razed by the British. It was not until July 1858 that the civil courts reopened, and only late in 1858 did Muslims gradually begin to reenter the city.[23] It was in 1858 that Ġhālib wrote, in a private letter to a friend, an unusual verse-sequence (qit̤‘ah) full of bitterly direct description:

Every armed English soldierEven by the end of 1858 a general permission to return had still not been granted, as Ġhālib noted; it was not given until November 1859, more than two years after the Muslims of Delhi had been expelled from their city—and the city to which they returned was irrevocably transformed.[25]

can do whatever he wants.

Just going from home to market

makes one’s heart turn to water.

The Chauk is a slaughter ground

and homes are prisons.

Every grain of dust in Delhi

thirsts for Muslims’ blood.

Even if we were together

we could only weep over our lives.[24]

A number of the changes made in the city were pointedly symbolic. After 1857 the densely built-up urban areas within three hundred yards of the Red Fort were razed to the ground. The fort itself was “almost entirely cleared of buildings, only a few relics of the old Mughal Palaces being allowed to stand,” with the resulting space occupied by “barracks for European troops.” The majestic Lahore Gate became a bazaar “for the benefit of the European soldiers of the Fort”; the famous Dīvān-e ‘ām (Hall of Public Audience) was “used as a canteen.” The general effect of the many kinds of punitive measures taken after the Rebellion was that people “had been taught to know their masters”; the Delhi area “received a lesson which will never be forgotten.”[26] Sikh troops were quartered in the Jāma‘ Masjid until 1862; several other mosques were not restored until the 1870s, and the Sunahrī Masjid, outside the Red Fort’s Delhi Gate, not until 1913.[27] The well-known Madrasah of Ḥusain Baḳhsh, where Hali had studied, stayed closed for eighteen years.[28] And Delhi College, its library destroyed by the rebels, was kept closed by the British until 1864, when it reopened; but despite its steadily increasing emphasis on English at the expense of Urdu, it was closed again in 1877.[29]

In the immediate aftermath of the Rebellion, moreover, the invasions, occupations, looting, slaughter, and expulsion of population were followed by further disasters. As Hali put it, after the British reconquest the city became a “howling wilderness.”[30] In 1860, Ġhālib summed up the sufferings of Delhi:

Normalcy was very slow in returning. Ġhālib continued to mourn the death of a great number of his friends—on both sides. Among the British dead, “some were the focus of my hopes, some my well-wishers, some my friends, some my bosom companions, and some my pupils in poetry.” And among the Indians, “some were my kinsmen, some my friends, some my pupils and some men whom I loved.” Now “all of them are laid low in the dust.”[32]Five invading armies have fallen upon this city one after another: the first was that of the rebel soldiers, which robbed the city of its good name. The second was that of the British, when life and property and honour and dwellings and those who dwelt in them and heaven and earth and all the visible signs of existence were stripped from it. The third was that of famine, when thousands of people died of hunger. The fourth was that of cholera, in which many whose bellies were full lost their lives. The fifth was the fever, which took general plunder of men’s strength and powers of resistance.[31]

The destruction of the neighborhoods, landmarks, and customs of the city was such that, to Ġhālib, Delhi itself had died: Delhi was “a city of the dead.” Did someone ask about Delhi? “Yes, there was once a city of that name in the realm of India.” Whenever his friends inquired about some notable Delhi person or occasion, he replied that Delhi was finished: “All these things lasted only so long as the king reigned.”[33] In a pessimistic letter to a friend, Ġhālib quoted one of his own shi‘rs (two-line verses): “A sea of blood rolls its waves—if only this were all!/Wait and see what else now lies before me.”[34] The image obviously rang true for him: two years later he described his life since the Rebellion as that of “a swimmer in a sea of blood in this city.”[35]

But life had to continue somehow. From 1858 onward, Ġhālib sought to get his pension restored; this proved to be difficult, for he was suspected of collaboration with the rebels, a charge he vehemently denied. He needed the support of the chief commissioner, Sir John Lawrence: “I therefore wrote in the praise of this man of high splendour a ghazal on the theme of spring, congratulating him on his victories and singing of the freshness of the breezes of the unfolding season, and sent it off by post.” He received instructions to resubmit his petition through the commissioner; but when he did so, he was told that “there was no call whatever for a letter comprising nothing but praise and congratulation.”[36]

Ġhālib had literary sufferings to endure as well. He himself had never kept copies of his own verse, and the two great private libraries in which his friends had carefully collected his works had been sacked and wantonly destroyed by British troops—as had the library at the Red Fort, too. He feared the loss of the poetry that was his life’s great achievement. “A few days ago a faqir who has a good voice and sings well discovered a ghazal of mine somewhere and got it written down. When he showed me it, I tell you truly, the tears came to my eyes.”[37]

Finally, in May 1860, after so much uncertainty and so many rebuffs that Ġhālib had almost given up hope, the pension was restored and the arrears paid in full. Ġhālib received from Sir John Lawrence a formal letter in Persian, duly written on paper sprinkled with gold dust, thanking him for his laudatory ghazal. This, together with a regular pension he had been receiving for some time from the nawab of Rampur, eased his financial situation somewhat. In February of 1863, his courtly rights—to attend at government durbars and to have the traditional robe of honor bestowed on him—were finally restored. He attended his last durbar in December 1866, where for the first time since the Rebellion these ceremonial robes and gifts were actually presented to him.[38] Although Ġhālib’s health was failing, and his finances were never what he wished, the flow of letters to and from his many friends and shagirds continued to sustain him. He died in 1869.

| • | • | • |

In 1857 Azad, twenty-seven years old, had been working with his father at the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār Press. The rebels arrived so suddenly, and seized the city so rapidly, that people were left stupefied. This abrupt downfall of the British was, as the Dihlī Urdū Aḳhbār editorialized, a reminder of the Day of Judgment, and was thus “meant to scourge us into obedience to the Divine Will.” It was an event so amazing as to be scarcely credible: “Did what we saw really take place in fact, or did it pertain to the realm of dreams?”[39]

After the initial shock, Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir successfully readjusted his loyalties. He apparently tried to save the life of his friend and former colleague, Francis Taylor, the principal of Delhi College, by hiding him from the mob that sacked the college and destroyed its library. The next day the presence of the fugitive was discovered; Francis Taylor, forced to flee in disguise, was caught and beaten to death in the street.[40] But when Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir published an article about the killings of various Englishmen, he went out of his way to blacken Francis Taylor’s character. With his years of experience in the collector’s office, Maulvī Muḥammad Bāqir then did what many others were doing: he reported to the new center of authority, the court. The emperor presented him with a robe of honor, and he became a regular advisor, performing a variety of administrative duties.[41] It seems that on one occasion he even took to the field in command of “two companies of infantry and one of cavalry,” to rescue a revenue train that was being attacked by bandits on its way to Delhi.[42]