Dorothy Kingsley: The Fixer

Interview by Pat McGilligan

In Chicago, where she and her husband had a business layover on their way to the East Coast, I met with the former MGM screenwriter Dorothy Kingsley for a leisurely lunch at a downtown hotel.

Almost eighty, she resides in northern California, and it has been twenty years since her last motion picture credit. But Kingsley still travels in the high-society circles that she grew up in, as a young socialite, in exclusive Grosse Pointe, Michigan. In New York City and Washington, D.C., Kingsley and her husband had a pending whirl of engagements—including dinner with former White House Chief of Staff Al Haig—and then she was off to Florida to attend the opening of a play written by one of her sons.

The week prior to our interview she was at a social gathering with media-sports magnate Ted Turner. She buttonholed Turner about an idea she had for updating Angels in the Outfield (1951), one of her few nonmusical films: she suggested substituting San Diego football for Pittsburgh baseball, and a Mexican migrant boy for the white-skinned little girl of the MGM version. Turner, who owns the MGM backlist of films, was noncommittal, but Kingsley was hopeful that she might yet get the project off the ground.

Kingsley has family ties to show business. Her mother was a legitimate actress, with appearances on Broadway and in silent pictures, and her father was a newspaperman and press agent. But their divorce brought her to Michigan, and it was her own divorce, after an unsuccessful first marriage, that brought her to California in the late 1930s. An ability to think up quips on the spot landed her, first, a stint as a radio comedy writer for Edgar Bergen, and, eventually, a job as an MGM contract writer, where Kingsley specialized in patchwork construction and on-the-spot dialogue for frothy musical come-

dies—especially the spectacular, escapist Esther Williams vehicles, and later on, the more prestigious Broadway adaptations. Her motion pictures are invariably lightweight and lavish, entertaining and jokey without any overt social significance. Although something of an anachronism nowadays, they were popular with audiences in the years following World War II.

Though Kingsley could originate stories, she tended to do adaptations. She often worked without credit; and though hers is usually a co-credit, she usually worked alone, before or after the other screenwriters had finished up. Her value as an MGM team player was enhanced by her modesty, her flexibility, and—photographs attest—her relative youth and winsome, blonde good looks.

Kingsley is a vanished breed: the studio utility player. But her ability to rethink a scene or to provide an appropriate snapper in a situation was much needed and much admired in the assembly-line days. And her stature among her generation of peers is evidenced by a string of Academy Award and Writers Guild co-writing nominations for her scripts in the 1940s and 1950s.

Dorothy Kingsley (1909–)

1941

Look Who's Laughing (Allan Dwan). Uncredited contribution.

1942

Here We Go Again (Allan Dwan). Uncredited contribution.

1943

Girl Crazy (Norman Taurog). Uncredited contribution.

1944

Bathing Beauty (George Sidney). Co-script.

Broadway Rhythm (Roy Del Ruth). Co-script.

1946

Easy To Wed (Edward Buzzell). Adaptation of Libeled Lady .

1948

A Date with Judy (Richard Thorpe). Co-script.

On an Island with You (Richard Thorpe). Co-script.

1949

Neptune's Daughter (Edward Buzzell). Script.

1950

Two Weeks with Love (Roy Rowland). Co-script.

The Skipper Surprised His Wife (Elliott Nugent). Screen story, script.

1951

Texas Carnival (Charles Walters). Co-story, script.

Angels in the Outfield (Clarence Brown). Co-script.

Cause for Alarm (Tay Garnett). Uncredited contribution.

1952

It's a Big Country (multiple directors). Episode 6 (story, script).

When in Rome (Clarence Brown). Co-script.

1953

Dangerous When Wet (Charles Walters). Story, script.

Small Town Girl (Leslie Kardos). Co-script.

Kiss Me Kate (George Sidney). Co-script.

1954

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (Stanley Donen). Co-script.

Dorothy Kingsley in Pebble Beach, California, 1988.

(Courtesy of Dorothy Kingsley)

1955

Jupiter's Darling (George Sidney). Script.

1957

Don't Go Near the Water (Charles Walters). Co-script.

Pal Joey (George Sidney). Script.

1959

Green Mansions (Mel Ferrer). Script.

1960

Can-Can (Walter Lang). Co-script.

Pepe (George Sidney). Co-script.

1967

Valley of the Dolls (Mark Robson). Co-script.

Half a Sixpence (George Sidney). Adaptation.

Television credits include creator of TV series "Bracken's World."

Academy Awards include best-screenplay nomination for Seven Brides for Seven Brothers .

Writers Guild awards include best-script nominations for On an Island with You, Angels in the Outfield, Kiss Me Kate, Don't Go Near the Water, Pal Joey, and Can-Can. Seven Brides for Seven Brothers won the Best-Written American Musical award in 1954.

The reference books are a little sketchy on your background. How and why did you come to Hollywood as a writer?

How it started? I was in Detroit, left with three little boys, and I wanted to make some money. I had a very severe attack of the measles, and while I was in bed listening to all the radio programs I began to think, "You know, I could write something that funny. . . ." So I wrote some stuff out for Jack Benny and others, and sent it in . . .

It was impossible to get hired if you were a woman gag writer, as there wasn't such a thing at the time. Especially one that young. I had a friend who lived in Los Angeles, and I came out to visit her and made the rounds of various agents. They all said, "What experience do you have?" I said, "I haven't had any, but here are samples of my work." They said, "We can't handle you if you haven't had any experience." Well, how could you get experience if they wouldn't handle you? It was a "chicken or the egg" situation.

Finally I found an agent who liked my work and said he'd take a chance on me. I went back home, packed up the children, and drove out here. When I went to see the agent, he was out of business! Here I was, and I had to start all over again.

Had you any prior occupation?

No, no. I was what you call a socialite in Grosse Pointe [an exclusive suburb of Detroit, Michigan].

The biographical sketches say that you are from New York .

I was born in New York City, on Park Avenue, as a matter of fact, if we want to be explicit.

Were your parents wealthy?

My father, Walter J. Kingsley, was a very well-known man in New York. He started out as a foreign correspondent with the London Daily Express from England. He covered the Boer War and the Boxer Rebellion, all that sort of thing. Then he went into public relations and handled people like Sarah Bernhardt, George M. Cohan, the kaiser (before the war), the mikado, Florenz Ziegfield . . .

My father was a fabulous guy, but my parents divorced and I went to

Detroit with my mother. She remarried, and I was brought up in Grosse Point from about the age of thirteen on.

Did your mother have an occupation?

Her name was Alma Hanlon. She was an actress for a while.

On Broadway?

She did a few things on Broadway—The Red Mill, for one. Then she did some movies, including a picture called The Whip [1917, directed by Maurice Tourneur].[*] But she never liked acting, so when she went to Detroit, she retired. Her husband was well known in Detroit.

As an industrialist?

No, he owned a lot of property. I was brought up with all the automobile people, the Fords, the Briggses, the Sorensons . . . Growing up, we used to go to the forge and watch them pour the steel at night. Everything [in Detroit] was automobiles, automobiles!

Still, you had this family background of show business .

Not really, because I didn't spend any time with my father, to speak of. I remember visiting him once. His office was in the New Amsterdam Theatre building and there were beautiful Ziegfield girls waiting around, and Fanny Brice and Will Rogers. But I didn't have much contact with him, and I was brought up in an entirely different way.

So now you're out in Hollywood, without an agent, with three little boys in tow . . .

I started going to offices again and trying to get people to read my stuff. It was hard, because I stutter in the first place, now and then, and I certainly looked like anything but a gag writer. And I had no experience as a comedy writer, except on the school papers.

What did you look like—if you looked like anything but a gag writer?

I had blonde hair down to my waist, I was very young, and I looked much younger than I was—about fifteen. And they had never seen any women gag writers or comedy writers.

But I happened to meet Constance Bennett and we became friends. She was a big star then, and appearing on all these radio programs. She said, "You write much better stuff than what they give me," and she took a couple of my gags and used them on one of her shows—"The Pepsodent Hour," I think it was.

That's when you started writing radio gags for Bob Hope?

Oh, that's a pitiful story. I went in to see someone—I think he was the account representative for "The Pepsodent Hour"—and he said, "Your stuff

* Alma Hanlon's screen appearances include Keep Moving (1915); The Final Curtain, The Devil's Prayer-Book, The Faded Flower, Gold and the Woman, and Wild Oats (all 1916); God of Little Children, The Golden God, The Great Bradley Mystery, The Law That Failed, The Mystic Hour, and Public Defender (all 1917); Sins of the Children and When You and I Were Young (both 1918); and The Profiteer (1919).

is good, but we're up to here in writers. I don't dare hire another writer. Bob [Hope] won't let me. So I'll put you on my private payroll . . . at $75 a week. I'll call you and let you know what the subject is going to be each week. You bring your stuff in to me quietly, and I'll slip it in with all the other writers', and if Bob uses some of it, or quite a bit of it eventually, I'll tell him it comes from another writer and that he should hire you. . . ."

I started to give him some gags, and when I listened to the show, I heard Bob using some of my stuff. But nobody knew about this, except for the account representative. It came Christmas Eve day, and I was supposed to come in and get my check for Christmas—for my three little boys—and when I asked to see the account representative, they told me, "We're sorry, you can't. He has had a nervous breakdown and is in the hospital . . ." (Laughs .) That was the end of that.

Then I saw an ad in the paper in the employment section asking people to submit two different scenes to Edgar Bergen, who said he would read anything submitted. So I wrote one for Bergen and the other I wrote for a guest star—I used Clark Gable, I think. Bergen got four hundred of these submissions, I understand, and he selected two people. Another young man and me. We went and were interviewed, and Bergen said he would take us on for a month, I think it was, and let us sit in with the other writers at about $50 a week. At the end of the month, he let the other boy go and he kept me on. Anyhow, I was with Edgar for several years at the time when he was on the top show on radio. We wrote for all the top stars.

I'm surprised you say you just happened to meet Constance Bennett. You couldn't go to Hollywood today and just bump into Meryl Streep. Was the social whirl more fluid in that you could just meet somebody like that?

Well, my background was such that I could meet people socially.

Then was working for Edgar Bergen your first professional writing job?

Yes. We'd select a subject that we were going to talk about, perhaps something of interest to the guest star, and we'd invent jokes about it. . . .

For example, we had Clark Gable [on the show], who at that time had a ranch out in the valley, and he was very interested in ranching. I remember I had Charlie [McCarthy] say to Edgar, "What's a gentleman farmer?" and then, "Someone who takes his hat off in a grain elevator!" Little things like that.

Then I had always wanted to get into the picture end of things, so I started writing scripts and submitting them [to studios]. Arthur Freed got hold of one, and he thought I had promise. I was taken over to MGM by my agent. Arthur said he'd like to hire me and put me on contract. I said fine, and he asked how much I got [from Edgar Bergen], and he doubled what I was getting. I liked Edgar very much—he was very talented—but I was grossly underpaid on Bergen's program, and I wasn't under contract.

When I told Edgar, he went wild. In fact, I remember I was going to stay

with him for two more programs, and Gary Cooper was on one of them. During a rehearsal I walked in the studio and sat down front, and Edgar, who was talking to Gary, turned and said to me, "What are you doing here? Are you slumming?"

So I went to work for Arthur [Freed]. He had a picture shooting called Girl Crazy [1943]. The writer was off somewhere doing something else, so he asked me to go down [to the set] and just do a little work. That was my first picture, with Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney.

My list of credits for you shows that Bathing Beauty [1944] was your first movie .

While I was working on Girl Crazy, I met [producer] Jack Cummings, who was having a lot of trouble with a picture called Bathing Beauty . I had some ideas about it, so he asked [MGM executive] Sam Katz if he could have me to work on it. There'd been a million writers on it [before me][*] but the script was just bleh, lying there. They couldn't shoot it, even though they had commitments with Esther Williams and Red Skelton, with Harry James, the trumpet player, and with Xavier Cugat, the cha-cha-cha man. They had shot the musical numbers and they had no story! They had shot a great number with Xavier Cugat, only nobody in the script had any reason to be there to see this number!

I had to think up something and then send a page down [to the set] for them to shoot. It was really wild. That's not the way you should make a picture, on the whole. I had a real baptism of fire. But the picture worked out, it was a big hit, Esther's first big picture.

During the war, people liked the escapism. I was told that Bathing Beauty was the biggest hit in Russia! Because it was gay and light and had so many pretty girls [in it]. It was too ridiculous!

In radio you were writing bits and pieces. Here, you were beginning to write wholesale scripts .

Outside of Girl Crazy, the whole thing.

How did you adapt to the visual demands of motion pictures?

It was easier [than radio]. You could use the camera to do things instead of just talk, talk, talk.

Did you have to learn to think visually as a writer?

I learned through practice. Jack kept me busy, busy, busy. Arthur Freed always laughed, "I bring this girl to the studio—and I can never get her. She's always busy with these other people."

Were there many other women writers at MGM?

There was Zoë Akins. (Laughs .) I'll tell you a funny anecdote about that.

* In the official files of the Writers Guild of America (formerly the Screen Writers Guild), seven writers share credit for writing Bathing Beauty .

Zoë was a playwright, originally. She was very bright, but no longer very young, or at least as young as I. I remember I was working for some producer, once, who used to have his wife read all of his scripts [and give him an opinion]—which, incidentally, drives a writer crazy, because the wife will always come back and say, "I don't think she should wear a polka-dot dress in that scene. . . ." (I used to say, "Why don't you let your wife write the script?")

One night we went to a party and I met the wife. She looked at me and said, "This is Dorothy Kingsley!?!" She thought I would look like Zoë Akins, who was past her prime.

I remember another time—I was single at the time—when I was going out with Arthur Hornblow, a very good producer. We were having dinner with Billy Wilder, who was going with an attractive girl. During dinner Billy turned to his girlfriend and said, "We don't have any writers like this at Paramount!" And she said, "No, and we don't need them!" (Laughs .) Because I was kind of unusual, at that age.

Helen Deutsch was in and out; there was Isobel Lennart, who was a love; Dorothy Cooper, who started as a junior writer; and Marguerite Roberts . . .

Was there camaraderie among the women writers?

Oh yes. Isobel and I were very close. She used to run into my office [to talk] all the time. She was a "real writer."[*] I never think of myself as a "real writer." I only wrote because I needed the money. I had no desire to express myself or anything like that. I couldn't care! Couldn't have cared less.

When I got home [at night], I never thought about my work or mentioned it. I mean, I wanted to do a good job, but I certainly wasn't going to pace the floor at night. Isobel lived for her work. She would get up in the middle of the night and write down a line. If someone didn't like her script, she'd throw up. I just didn't care. Just give me the money. I needed the money.

Was there a division of subject matter for women writers, particularly subjects that the studios tended to ask you to do over and over again because you were women?

No. I don't know. I never thought about it particularly. It depended. I did an awful lot of the old MGM musicals—three quarters of the Esther Williams things. You just did the best you could with what you were working with [there], you know. They were after a certain thing, a kind of spectacle. Esther was very popular. Finally, I ran out of ways to get her in the water.

I know some things were offered to me that I wasn't too keen on, but not because I was a woman.

* Author of the musical Funny Girl, Isobel Lennart wrote many distinctive films, alone or in collaboration, including Anchors Aweigh (1945), It Happened in Brooklyn (1947), East Side, West Side (1949), Love Me or Leave Me (1955), The Sundowners (1960), Please Don't Eat the Daisies (1960), Two for the Seesaw (1962), and Period of Adjustment (1962).

Was it a plus or a minus for a screenwriter that everything was such a committee decision at a studio like MGM?

You had to go through a lot of people. Normally, that's a minus, because everybody wants to get into the act. They all felt they had to have some input. But I was with pretty powerful producers, as a rule, where once you got the okay, you didn't have too much trouble.

Did you have little tricks, or a specific strategy, when it came to story conferences?

If we were having a conference and I wanted to sell a story or any idea, I would pretty much act the thing. That helped, if they could see me getting up and could hear how the dialogue would sound.

Another little trick I had was, if I really wanted to get a certain line or idea over, and I wasn't sure how the producer would take it, I would usually say [something like], "As you suggested the other day . . . ," when they'd never suggested anything at all. But if they thought they did, fine; it was very hard for them to say no. There are little tricks like that, occasionally. (Laughs .)

Did you learn more from the producers or the directors at MGM?

Directors more than producers. Now, Jack Cummings was an excellent producer, though he was L. B.'s [Louis B. Mayer's] nephew, which reacted against him. He let it react against him. Everyone else would go up and ask L. B. for something, but Jack never would because he was his nephew. He went through every department in the studio—cutting, music, sound, everything. He had a good story mind, too. He knew about everything and he was one of the best producers.

Give me an example of a director who taught you something .

Roy Del Ruth. He was one of the first directors of musicals, and he was tough. He would go over a scene with us and say, "You don't need that line. You can say it with the camera." I learned to write less. I learned not to use dialogue if I could show something another way. And if I was using dialogue, [I learned] to make sure the audience knew what the character was thinking.

I think the writing is so overdone today. People don't use the camera. People will talk and talk and talk. And quite often they don't resolve everything. To me, a story has got to be resolved at the end and leave you satisfied . They don't do that in many pictures nowadays.

There was a line that [producer] Joe Pasternak always used to say if he didn't think the scene actually told what he thought the audience wanted to know. He'd say, "Give me a house number." Let us know what the number of the house is—what's happening? You see things on TV nowadays where you suddenly say, "What? How did they get out of that?" I think writers today are very sloppy and they cheat. They'll just jump ahead and you don't see what happened or why.

When you see the MGM musicals today, it is hard sometimes for someone

who is not a buff to differentiate between the directors, people like George Sidney or Walter Lang or Charles Walters .

Oh, Chuck Walters. He was very good. The only thing, I used to think he sometimes didn't get enough close-ups.

I remember there was a funny scene in one of his pictures with Red Skelton—Texas Carnival [1951], I think. Red was posing as someone else, a big-time millionaire, who gets into this poker game where they're using jelly beans as poker chips. He keeps eating his and they think, "Oh, my God, five thousand means nothing to this guy. . . ." Afterwards, when he finds out how much he ate, he nearly dies. They ask him, "How are you going to make it up?" and he says, "If I can get a stomach pump, I know where I could locate $10,000!" I probably shouldn't say this about poor Chuck, but he wasn't in close enough on Red to get the full effect. It played, but Chuck used to get a little tired of taking close-ups, I think. Today, you know, they're practically in their tonsils in all the pictures.

George Sidney was very artistic, oh boy. Really artistic—and one of the real showmen of the studio. The others were in it more for the business, but George Sidney used the camera beautifully.

Did the MGM directors have differences in how they related to the script?

They were all of different temperament. With all of them, you'd talk it over. Some of them had good suggestions, which I always welcomed. Some of them didn't have anything to say, to speak of.

I didn't mind changing things at all. A lot of, as I call them, "real writers," to them the line became sacred scripture. I couldn't have cared less. You could change anything if I didn't think it really hurt the script. I always felt if you couldn't write another line as good as the one you wrote before, you weren't that great anyway. One of the reasons I had a lot of people asking for me, I think, is because I was easy to get along with.

Did the MGM stars have much script influence?

You didn't really work with them that way, until it was all done. Then they might come in and say, "I don't feel comfortable with this line . . . ," and you'd change it. They were all very easy and flexible.

What about someone like Esther Williams?

She was easy to deal with. But they were not soul-searching lines. She knew what she was good at.

Being there all the time under contract, when you started a picture certain actors would come in and say, "Don't you the think I should have that line instead of this one, or don't you think I should do this [in that scene]?" One actor in particular I remember, he thought he was rather pretty and he used to flutter his eyelashes at me. He must have thought I would be impressed by something like that. I won't tell you who it was.

I would think that sort of lobbying for dialogue would be frowned on in the MGM system .

Oh, the studio wouldn't know anything about it. They would come right into the office and talk to me.

Conversely, if you liked the star a lot, would you butter up the part?

No. The script was the main thing. Whoever I thought would be the best to do it would get the lines.

Strangely enough, after I'd been at MGM a while, I sort of got the reputation as a fixer in construction. They'd call me down [to the set] all the time, just as a "favor." Because I was under contract and knew everyone, I'd get calls all the time [to help out]. Some producer I knew would ask, "Would you mind coming down to the set? We're having a little problem with this or that. . . ." It would be a script by someone like Philip Barry, long gone back to Broadway, and they were stuck with some little problem. I was good-natured about it. I did many pictures like that.

Can you give me an example?

I remember once, Loretta Young was doing a picture with [her husband] Thomas Lewis, the producer [probably Cause For Alarm in 1951, co-written by Lewis]. They had a preview and it didn't go over too well. The producer asked me to run the picture with Jack Cummings. We could see what was wrong. There was something left out [of the story line], which didn't explain why this woman felt the way she did about something; there was one scene missing, really. It wasn't hard to fix at all.

MGM kept me working all the time. Everyone was awfully nice to me, very protective, because there I was so young, with the three little boys. I remarried finally and I had three [more] children—six, ultimately!—but I always worked practically up to the time they took me to the delivery room. I remember Joe Pasternak would call, just as I came out of the delivery room, asking, "What are we going to do about Esther . . . ?" Everybody used to kid me about it. My contract [at MGM] went on forever, and kept going up, up, up.

Did you have much freedom in what you were assigned to work on at MGM?

You'd suggest something, or they'd bring in something from Broadway. I'd say 70 percent of the things I wrote came about because I went to the producer and said, "How about this?" or "I've heard about this and I'd like to write it. . . ."

(Laughs .) Whenever [producer] Joe Pasternak didn't have a picture going, or if he didn't have an idea for one, he used to put an item in the columns that said, "Dorothy Kingsley's working on a new script for Pasternak called 'Baby Needs Shoes.' "[*] Now, "Baby Needs Shoes" was never made—there

* Hungarian-born producer Joe (Joseph) Pasternak started out as a waiter and busboy at Paramount studios before working his way up to executive status in the 1930s. He was known for his lightweight hit musicals, first in Europe, then in Hollywood at Universal and, later, at MGM. Pasternak is also mentioned in the Walter Reisch and Daniel Taradash interviews,

"My contract went on forever": Dorothy Kingsley at her desk at MGM in the 1940s.

(Photo: USC Special Collections)

was no such picture—but either Isobel Lennart or I was always working on it!

Did you have some particular interest in musicals and musical comedy, or did it just evolve that way?

I started out that way and it just evolved. I love comedy. I love music. I had a box at the Hollywood Bowl forever, and in San Francisco, when I lived there, we always went to the symphony.

I loved working with the songwriters, because they were so clever. As a rule, you'd write the script, or certainly a draft, before you ever talked to a songwriter. I'd always indicate so-and-so should have a song "here." You'd come in and talk to them and say what you wanted expressed in a song, talk over the plot, and they'd come back later and play something wonderful. And very often, when you talked with them, something else would open up.

Cole Porter was so charming, and he didn't take himself seriously at all. We went to his house for lunch one day and he gave me a recipe for a fabulous cold soup. In fact, there was one song of his that didn't work out too well, and he just asked, "Do you want me to write another one?" We used another song of his that wasn't in the original score of Kiss Me Kate —"From This Moment On." George Sidney let Bob Fosse help direct that number. That was his [Fosse's] first real break—and the best number in the show.

Sometimes the songwriters would have songs that we just had to fit in because they were so good. I remember talking with Frank Loesser one day, and he told me he had a good song but he didn't know what to do with it. Then Frank played "Baby, It's Cold Outside" for me, and I liked it so much I wrote a scene for it with Esther [for Neptune's Daughter in 1949], and it won the Academy Award.

Nowadays, the Esther Williams films are really chuckled at. Were they, at the time, considered lesser vehicles by the studio?

No. There was the musical unit and there was the serious unit, but the musicals made great money. During World War II, you had fighting all over the world and people wanted to escape from all of the problems of the day, I think. The Esther Williams pictures were never taken that seriously, but she was popular. They were intended to get Esther into the theaters, they were spectacles, and they made a lot of money.

Only one picture didn't work and that was when Dore Schary was at the studio. I wanted to do a musical version of [Robert Sherwood's] The Road to Rome . I got Esther and Howard Keel [in the cast of Jupiter's Darling in 1955]. It was a satire and, in fact, we even had Hannibal's elephants painted pastel colors—orange and green. Dore was always against it, I must say. He was worried about doing satire and I have to agree with him: there were some wonderful visual things in it, even an elephant dance, but the satire didn't work. We took it out to a preview and I was sitting behind people in the front rows who took it seriously. It wasn't until halfway through the picture that someone in front said, "Oh, it's a satire." That's the only flop I had, I think.

Angels in the Outfield seems like quite a departure for you, not only because it is a baseball film, but because it came at the end of the Esther Williams cycle .

Oh, I was a big sports fan. I love baseball. I was brought up in Detroit with the Detroit Tigers. I'm a terrific football fan, too.

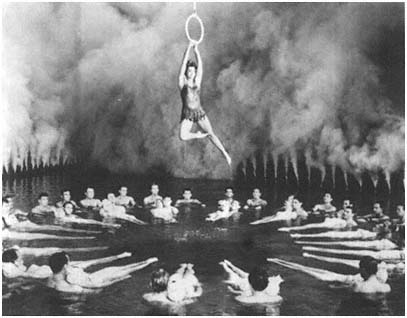

"They were spectacles and they made a lot of money": swimming star Esther

Williams, suspended above the pool, in one of the popular musicals of the era.

Because I had three little boys, I used to take them to boxing matches and things like that. In fact, well-known male stars used to ask me out partly because they loved the boys and were happy to take these little boys places.

Clarence Brown, who was a good friend, asked for me for the baseball picture with the Pittsburgh Pirates, and I said yes. Eisenhower's favorite picture was Angels in the Outfield . He ran it so many times that the staff said, "Please, Mr. President, not again . . ."

There is a tremendous religious aspect to that picture, and to the other one you wrote for Clarence Brown, When In Rome [1952].

Yes, though Clarence is not all that religious. It just happened.

But I am a Catholic, and there is an interesting story about the casting of Angels in the Outfield . We wanted a nice little girl to play the orphan in the movie. A lot of them applied. A maintenance man at MGM came to my office and said, "I have a little girl I think would be perfect in this. Would you consider her?" He brought her in, she was very cute, and I introduced her to Clarence Brown.

But she didn't have any experience, so we were considering other little girls. I went to Mass one morning, where I was saying a novena. Who should be in front of me, making a novena herself, but this little girl? Of course, I

knew darn well what she was making it for. So I went to Clarence and I said, "Clarence, this is the one! This is a sign!"

Though you have a lot of co-credits, it seems that you usually wrote alone, without a collaborator. On Seven Brides for Seven Brothers [1954], did Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett work on the script before or after you?

They worked on it [before me] and they didn't get along with Stanley Donen. They were lovely people, darling . . . but the script just wasn't coming out right, they were unhappy, and he was unhappy. They wanted to bow out.

Stanley Donen called me in and I looked at the script and said, "The big trouble in the original short story is that the Howard Keel character is the one that tries to get all of these boys married off, and that's not right. The girl has nothing to do, and she's got to be the one to engineer all this stuff." That was changed around and seemed to please everyone, and we went from there.

You worked with Frank Sinatra twice. How did you become involved with Pal Joey [1957]?

They were going to do Pal Joey at Columbia with Kirk Douglas. George Cukor was going to direct it. Lillian Burns, the assistant to Harry Cohn, called me and said, "This is very hush-hush, but as much as we like Kirk Douglas, there's only one person in the world who can play this . . . and that's Frank Sinatra. But Harry and Frank didn't speak. They've had this terrible feud for years." I said, "I can't believe that. Let's talk to Harry." So we went and talked to Harry Cohn. It was my first conference with him.

I said to Harry Cohn, "I love Kirk, but there's only one person for the part . . . Frank Sinatra." "Absolutely impossible," said Harry Cohn. "He wouldn't do it!" I said, "How do you know he wouldn't do it?" "I'm not talking to him," he said. "You mean you would let a thing like that stand in the way of a picture?" I asked. "There is no use [talking about it], because he wouldn't do it," he said.

So Lillian and I got together and I quickly did a synopsis of how the movie would go with Frank [in it]. Frank was making a picture somewhere and he had to drive to location every day. We got Abe Lastfogel of William Morris Agency to give him this synopsis to read on the way to location. Frank called me and said, "I'll do it." So I went to Harry Cohn and said Frank would do it. And Harry Cohn committed without ever seeing the script.

Was the script so very different from the play?

There was quite a difference. There was a lot more to it. We could enlarge it. Also, that was the first time a musical had been done that was a little sexy.

Did Frank Sinatra have any script input?

Oh, Frank has ideas of his own, of course. But Frank will attune himself to whom he's with and what he's doing. I remember when George Sidney [who ultimately directed the picture] and I went over to his house to discuss Pal Joey . He invited us for tea. It was beautifully served—everything was

just so. Frank was the perfect gentleman, always charming, always. He liked Pal Joey so much—what I had done with it—that he committed to Can-Can without a script. That is rare.

Which of your films are your favorites?

I like Pal Joey and I like Angels in the Outfield . The others, I always think, "Gee, why didn't we do this?" or "It should have been better. . . ."

What were your working circumstances like at MGM?

Well, I had a very lovely office, a desk, my secretary, a big davenport . . .

Typewriter?

I don't type, really.

Pencil and paper?

I had a secretary for a long time, and I would dictate it to her and she'd write it up. I'd look it over and scratch it up about six times. I'm very fussy that way. When she wasn't around, I'd just sit on the davenport with the yellow pad and pencil. That's how I'd write.

Door closed? Phone off the hook?

Not particularly. I'd just as soon be interrupted. Because I don't really like to write much. I only write because I like the money.

So, you can write with distractions?

Oh, yes. I remember, when two other writers and myself went with the Edgar Bergen show to New York for three weeks, we all worked in a big suite there, and the noise and the traffic left the others a wreck. It didn't bother me a bit, and I wound up writing more of those three shows than anyone.

I can sit down in the middle of Hollywood and Vine and write. As I told you, I turned everything off when I came home [at night], but when I had to do it, I could write with children crawling over the typewriter, always.