Daniel Mainwaring: Americana

Interview edited by Tom Flinn

This is one of the things that makes me very close to Dan Mainwaring—his experience of Americana, the nostalgia of the good things about small towns. I remember the smell of burning leaves at night in the autumn too. And I remember the smell of Christmas, the sparkle in the air at football games, and the sound of distant trains. And Dan remembers them all. He's a much underrated writer and he's a really quite noble man. He damaged himself with drink and he was very badly hurt by the blacklist.

Joseph Losey, quoted in Conversations with Losey, by Michel Ciment

Daniel Mainwaring (pronounced Man-a-RING) wrote both the original novel (Build My Gallows High ) and the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947). He alone is responsible for the thematic density of the film in which such ultimate noir elements as betrayal, the femme fatale, and the frame-up are combined with reckless abandon. After completing Out of the Past, Mainwaring, in spite of a brush with Hollywood's witch-hunters, went on to script three films that represent the perfect cinematic realization of the burgeoning middle-class paranoia of the fifties. The first of these was The Hitch-Hiker (1953, directed by Ida Lupino), in which Kansas desperado Emmett Meyers (William Talman) systematically terrorizes two average family men (Edmond O'Brien and Frank Lovejoy) on a fishing trip. The second was The Phenix City Story (1955, directed by Phil Karlson), based on the real-life struggle of Alabama Attorney General John Patterson against the ruthless, entrenched power of the vice rings that controlled Phenix City. The third was Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, directed by Don Siegel), a marvelous marriage of film noir paranoia, political hysteria, and a science fiction premise. In addition to this trilogy (which exhibits a remarkable consistency of tone), Mainwaring wrote The Lawless (1950) for Joseph Losey, as well as The Big Steal (1949), Baby Face Nelson (1957), and The Gun Runners (1958) for Don Siegel.

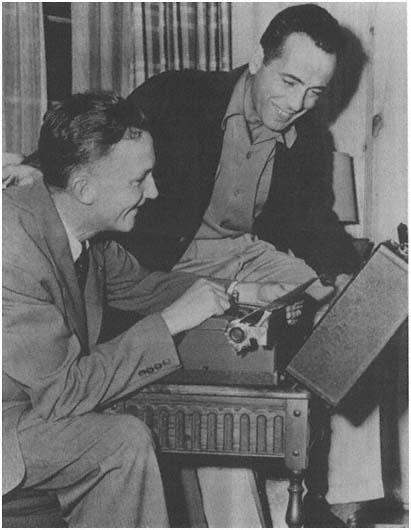

Daniel Mainwaring (left) posed with Humphrey Bogart. Bogart had agreed,

originally, to star in the film of Out of the Past . (Photo: British Film Institute)

The following remarks, which pertain to Out of the Past and RKO, were excerpted from comments Mainwaring made when he appeared at a seminar on the gangster film held at Northwestern University in the summer of 1972, a project sponsored by the University of Illinois in conjunction with the American Film Institute and supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C. Mainwaring prefaced his remarks with a short biographical statement.

Daniel Mainwaring (Geoffrey Homes) (1902–1977)

As Geoffrey Homes

1941

No Hands on the Clock (Frank McDonald). Script, based on his novel (as Homes).

Secrets of the Underground (William Morgan). Story, co-script.

1944

Crime by Night (William Clemens). Based on his novel (as Homes) Forty Whacks .

Dangerous Passage (William Berke). Story, script.

1945

Scared Stiff (Frank McDonald). Co-story, co-script.

Tokyo Rose (Lew Landers). Co-script.

1946

Hot Cargo (Lew Landers). Story, script.

They Made Me a Killer (William C. Thomas). Co-script.

Swamp Fire (William H. Pine). Script.

1947

Big Town (William C. Thomas). Screen story, script.

Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur). Story, script, based on his novel (as Homes) Build My Gallows High .

1949

Roughshod (Mark Robson). Co-script.

The Big Steal (Don Siegel). Co-script.

1950 The Eagle and the Hawk (Lewis R. Foster). Co-script.

The Last Outpost (Louis Gasnier). Co-script.

The Lawless (Joseph Losey). Screen story, script, based on his short story (as Homes) "The Voice of Stephen Wilder."

1951

Roadblock (Harold Daniels). Co-screen story.

The Tall Target (Anthony Mann). Co-story.

1952

This Woman Is Dangerous (Felix E. Feist). Co-script.

Bugles in the Afternoon (Roy Rowland). Co-script.

1953

Powder River (Louis King). Script.

Those Redheads from Seattle (Lewis R. Foster). Co-screen story, co-script.

The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino). Uncredited contribution.

1954

Alaska Seas (Jerry Hopper). Co-script.

Black Horse Canyon (Jesse Hibbs). Script.

Southwest Passage (Ray Nazarro). Co-script.

1955

The Annapolis Story (Don Siegel). Co-script.

A Bullet for Joey (Lewis Allen). Co-script.

As Daniel Mainwaring

1955

The Phenix City Story (Phil Karlson). Co-script.

1956

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel). Script.

Thunderstorm (John Guillermin). Script.

1957

Baby Face Nelson (Don Siegel). Script.

Cole Younger, Gunfighter (R. G. Springsteen). Script.

East of Kilimanjaro (Arnold Belgard, Edoardo Capolino). Co-screen story.

1958

Space Master X-7 (Edward Bernds). Co-screen story, co-script.

The Gun Runners (Don Siegel). Co-script.

1960

Walk Like a Dragon (James Clavell). Co-screen story, co-script.

1961

Atlantis, the Lost Continent (George Pal). Script.

The Minotaur [a.k.a. The Wild Beast of Crete ] (Silvio Amadio). Co-screen story, co-script.

Revolt of the Slaves (Nunzio Malasomma). Dialogue.

1965

Convict Stage [director unknown]. Script.

The Woman Who Wouldn't Die (Gordon Hessler). Script.

Television credits include episodes of "Rustler's Run," "The Californians," and "The Thin Man."

Books include One Against the Earth, as Mainwaring; and The Man Who Murdered Himself, The Doctor Died at Dusk, The Man Who Didn't Exist, The Man Who Murdered Goliath, Then There Were Three, No Hands on the Clock, Finders Keepers, Forty Whacks, Street of the Crying Women, Hill of the Terrified Monk, Six Silver Handles, and Build My Gallows High, all as Homes.

Daniel Mainwaring died on January 31, 1977, in Los Angeles. His Variety obituary noted that "in recent years he had [collaborated] in Europe with producer-director-author Hardy Krueger."

I went to Fresno State. . . . In the early twenties I worked as a crime reporter for the Los Angeles Examiner . . . . In 1935 I got my first job in the industry as a publicity man at Warner Brothers. Working in publicity you got to see and learn more about picture making than the writers did. . . . I didn't escape from the publicity racket until 1943. Bill Thomas of Pine and Thomas, who made very small and very bad pictures at Paramount, gave me my first real screenwriting job. I wrote six pictures in one year, all of which I'd just as soon forget except Big Town [1947]. At the end of the year, I fled to the

hills and wrote Build My Gallows High . Bill Dozier, head of RKO, bought it and me with it. Warren Duff, an ex-Warners writer, produced, Jacques Tourneur directed. Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Jane Greer were the stars. On the advice of Gallup's Audience Research, RKO changed the title to Out of the Past . I stayed at RKO until 1949. Howard Hughes dropped my option when I refused to work on I Married a Communist [1949]. He used that project to get rid of a lot of writers, directors, and actors. If you turned it down, out you went.

You'd written some mystery novels in the thirties. Did you sense different interests and different themes in this novel in the forties?

Well, Build My Gallows High was a different kind of book, entirely different. First I had a detective named Robin Bishop, and I got sick of him. Bishop got married and then got awfully soft, and I got fed up with him. I changed to Humphrey Campbell, who was a tougher one. With Build My Gallows High I wanted to get away from straight mystery novels. Those detective stories are a bore to write. You've got to figure out "whodunit." I'd get to the end and have to say whodunit and be so mixed up I couldn't decide myself.

What changes did you make [in the movie]from the novel?

Well, I haven't read the novel since about '46, but basically it was the same, although there were more characters in the novel.[*]

Was it told from Bailey's point of view?

From his point of view. The novel opened in Bridgeport, where he ran a gas station and the guy came looking for him. All the stuff in the mountains, the Tahoe and Bridgeport stuff, was in the novel. Much of the novel took place in that town and along the river. The fishing scene was in the book. That was one of the things that sold the book to pictures, the gimmick of the kid using a casting rod to pull the guy off the cliff. Warren Duff fell in love with that and bought the book.

The Mexican stuff was in there, too. I had been to Acapulco a couple of years before I wrote the book. It was just a little bitty town, not like it is today. There were very few cafes, and one hotel. I used to sit in this little cafe across from the movie house, and all day long there would be music blasting from the loudspeakers, so I thought I'd use that in a story someday, which I did.

The scenes in San Francisco, however, took place in New York in the

* An impossibly intricate story to synopsize, Out of the Past is about a double-triple-cross. A private detective re-encounters a former girlfriend and is lured out of a pastoral setting to San Francisco and Mexico to settle a score with old criminal associates. The girlfriend, who originally double-crossed him after she shot his boss, may or may not be double-crossing him again. Reviewer Bosley Crowther of the New York Times tried to keep up with the twists and turns, liked the film enormously, but admitted, "If only we had some way of knowing what's going on in the last half of this film, we might get more pleasure from it. As it is, the challenge is worth a try."

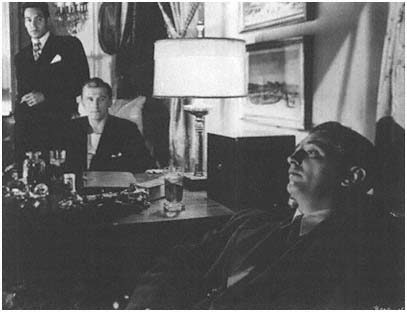

Novel into film: Richard Webb, Kirk Douglas, and Robert Mitchum in a tableau

from Out of the Past, directed by Jacques Tourneur. Scriptwriter/novelist Daniel

Mainwaring used his pen name, Geoffrey Homes. (Photo: Academy of Motion

Picture Arts and Sciences)

book. We switched to San Francisco because we wanted to shoot there. We did change the ending. At the end of the novel Bailey [Robert Mitchum] is killed by Whit's [Kirk Douglas'] men, not by Kathie [Jane Greer] and the police.

The title "Build My Gallows High" is from a poem and I never could find it again. It was a Negro's poem and I saw it somewhere. I happened to read it and jot it down.

Did you write the screenplay alone?

I wrote the first draft, and Duff wasn't sure about it. All I had done were those pictures for Pine and Thomas. When I finished and went on to something else, Duff put Jim [James M.] Cain on it. Jim Cain threw my script away and wrote a completely new one.[*] They paid him $20-30 thousand and it had nothing to do with the novel or anything. He took it out of the country and set the whole thing in the city. Duff didn't like it and called me back. (Frank Fenton had worked on it for awhile.) I made some changes and did the final. But that's the way things used to work. You'd turn around and spit and some other writer would be on your project.

* James M. Cain is interviewed in Volume 1 of Backstory .

What were some of the changes you made?

Originally we used a trick. The first script had the deaf-and-dumb boy as the narrator. We started with a shot of a stream with the boy fishing. Two guys came along, and one said to the other, "That's the kid who used to work for that son of a bitch Bailey." Cut to a close-up of the kid and a shot of the stream as raindrops begin to fall. Then you hear the voice of the kid saying, "He wasn't an SOB," and he told the story. Well, it flashed back twice, and it just didn't work.

At what stage did Jacques Tourneur work on the film?

After the script was completed.

Did you have any script conferences with him?

No.

Did you go on location?

Oh, I went up there but I didn't do anything. I just went up to look around.

I had some time off. . . . I liked it up there, and I just drove up to see what they were doing.

Did you like the way Tourneur handled the film?

He did what was in the script—very much so. One thing I didn't like was that mother [Ann's mother] in Bridgeport.

At one point I was struck by a similarity to The Maltese Falcon [1941] .

Well, don't think I haven't swiped from The Maltese Falcon often.

The thing which struck me was when Mitchum went in to see Douglas and said, "We have to have a fall guy ."

That was right out of The Maltese Falcon. Chandler swiped from Hammett. I thought I could, too.

How do you interpret that last business with the deaf boy? Are we supposed to think that the boy is purposely lying to her so she will go on to a better life?

Yes.

Even with the two people from the small town getting together and going away, it's not much of a happy ending because all of the interesting people are dead .

Well, the front office said, "Jesus, you can't end it with them dead there. You've got to put something on it." Nowadays they would have ended it right there with both of them dead.

Why did you choose not to stage the scene [in the novel] in which Kathie shoots Whit?

It was staged, but it worked out better the other way. There was a scene when Whit came back from Reno with the money and she shot him, but we found it was more effective if we stayed on Mitchum [Jeff Bailey], and he walks in and finds the dead man.

The first time I ever saw the film, they were showing it to some people on the lot. When Mitchum walked in and found that body lying there, all those people who worked on the lot said, "Oh no, not another one."

When you were doing the script, did you know that Robert Mitchum was going to play Jeff Bailey?

When I finished the script, I took it down to Newport where Bogart was living. He was going to do it, but Warners wouldn't let him. So then we took Mitchum. He had already done G.I. Joe [The Story of G.I. Joe, 1945], which was a beauty. He was fine, though he looks a little fat.

That was just before his trouble with the law .

He smoked marijuana all the time on the set. He had a vicious sense of humor. The executive producer on the film was a guy named Robert Sparks, a very nice guy, dignified and sweet. Sheilah Graham, the commentator, came on the set to see Mitchum, and she was talking to him when a drunken dress extra came up and started pestering Mitchum. Finally Mitchum had to tell him to get the hell out of there. Graham said, "Who was that?" Mitchum replied off-handedly, "That's a very sad story. That's our executive producer, Robert Sparks. He's an alcoholic." Sheilah was busily taking notes the whole time, but luckily the publicity man overheard, and afterwards he took her aside and said Mitchum was kidding. Well, she wouldn't believe him and finally had to be taken up to Sparks' office to meet him.

How did they decide what actor would play the part? Did they have readings or did they just say, "Well, Rhonda Fleming is available"?

Rhonda Fleming was under contract. Mitchum was under contract. Jane Greer was under contract. They fit the parts, so we used them. They [the studio] had to pay them anyway.

Had Jane Greer made many pictures before this one?

No, I think this was her first big role. Warren Duff decided to use her. They tested her and she was fine. She was in The Big Steal next.

How did you get along with Duff?

He was a sensitive man and a fine producer to work for. [Dore] Schary didn't like him. When Schary came to RKO, he fired him. Schary didn't like Out of the Past because it had been bought before he came. He didn't like anything that was in progress at the studio when he got there. He tried to get rid of all of them. He just threw them out without any decent publicity.

One thing I noticed was there are a lot of small towns in your films, and these small towns turn out to be not very safe places .

Small towns are miserable places. Farmers I know up in the San Joaquin Valley have been trying to put out a contract on [Cesar] Chavez to get him knocked off for organizing the migrant workers. They're sweet people.