Leigh Brackett: Journeyman Plumber

Interview by Steve Swires

She wrote that [The Big Sleep] like a man. She writes good.

Howard Hawks, quoted in Hawks on Hawks

In many ways, Leigh Brackett was the archetypal Howard Hawks woman. She was energetic, stubborn, self-sufficient, and self-deprecating, as were many of the female (and for that matter, male) characters in her scripts for Hawks' The Big Sleep (1946), Rio Bravo (1959), Hatari! (1962), El Dorado (1967), and Rio Lobo (1970), as well as for Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye (1973). Besides being one of the few successful women screenwriters, she was one of the earliest successful women science-fiction writers, having entered the field professionally in 1939. Her best-known character is the larger-than-life swashbuckling hero Eric John Stark, who first appeared in the pages of Planet Stories in the 1940s and who returned in a series of novels she wrote for Ballantine Books.

Brackett was married to the well-known science-fiction writer Edmond Hamilton, and they lived in Kinsman, Ohio, where, according to her husband, she spent her time "at a typewriter under the eaves of our old farmhouse, writing science fiction and mysteries, with frequent interruptions to run a tractor, clear paths in the woods, and spray the orchard." She also edited a collection of her husband's stories, titled The Best of Edmond Hamilton .

(This interview was conducted several years before her death and the post-humous release of The Empire Strikes Back, her final screen credit.)

Leigh Brackett (1915–1978)

1945

The Vampire's Ghost (Lesley Selander).[*] Story, co-script.

1946

Crime Doctor's Manhunt (William Castle). Script.

The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1959

Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1961

Gold of the Seven Saints (Gordon Douglas). Co-script.

1962

Hatari! (Howard Hawks). Script.

13 West Street (Philip Leacock). From her novel The Tiger Among Us .

1967

El Dorado (Howard Hawks). Script.

1970

Rio Lobo (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1973

The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman). Script.

1980

The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner). Co-script.

Television credits include episodes of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents," "Checkmate," "Archer" and "The Rockford Files."

Books include No Good from a Corpse, Shadow over Mars (a.k.a. The Nemesis from Terra ), The Starmen (a.k.a. The Galactic Breed or The Starmen of Llyrdis ), The Sword of Rhiannon, The Big Jump, The Long Tomorrow, Eye for an Eye, The Tiger Among Us (a.k.a. 13 West Street ), Rio Bravo, Follow the Free Wind, Alpha Centauri—or Die!, The People of the Talisman/The Secret of Sinharat, The Coming of the Terrans, Silent Partner, The Halfling and Other Stories, The Ginger Star, The Hounds of Skaith, The Reavers of Skaith, The Best of Leigh Brackett, The Best of Planet Stories No. 1: Strange Adventures on Other Worlds (edited by Brackett), and The Best of Edmond Hamilton (edited by Brackett).

Brackett was a winner of the Western Writers of America Golden Spur Award and of the Jules Verne Fantasy Award. In her official Writers Guild résumé, she was also noted as "a proud Ohio potato grower."

Your first screenplays were for The Vampire's Ghost [1945], a "ten-day wonder" at Republic, and Crime Doctor's Manhunt [1946], part of the Crime Doctor series at Columbia. You went from those B movies to The Big Sleep,

directed by Howard Hawks, in 1946. How did you manage so prestigious an advancement?

The "ten-day wonder" was because my agent, Hugh King, had been with Myron Selznick, my agency at that time, and he had gone over to Republic as story editor and had sort of managed to shoehorn me in because they were doing this horror film. They decided to cash in on the Universal monster school, and I had been doing science fiction, and to them it all looked the same—"bug-eyed monsters." It made no difference. I did The Vampire's Ghost there, and just out of the clear blue sky this other thing happened, purely on the strength of a hard-boiled mystery novel I had published. Howard Hawks read the book and liked it. He didn't buy the book, for which I can't blame him, but he liked the dialogue and I was put under contract to him.

You worked on the screenplay of The Big Sleep with William Faulkner. I wouldn't say that you collaborated, but both of your names are in the credits as having written the script, along with Jules Furthman .

I went to the studio the first day absolutely appalled. I had been writing pulp stories for about three years, and here is William Faulkner, who was one of the great literary lights of the day, and how am I going to work with him? What have I got to offer, as it were? This was quickly resolved, because when I walked into the office, Faulkner came out of his office with the book The Big Sleep and he put it down and said: "I have worked out what we're going to do. We will do alternate sections. I will do these chapters and you will do those chapters." And that was the way it was done. He went back into his office and I didn't see him again, so the collaboration was quite simple. I never saw what he did and he never saw what I did. We just turned our stuff in to Hawks.

Jules Furthman came into it considerably later, because Hawks had a great habit of shooting off the cuff. He had a fairly long script to begin with and he had no final script. He went into production with a "temporary." He liked to get a scene going and let it run. He eventually wound up with far too much story left than he had time to do on film. Jules came in and I think he was on it for about three weeks, and he rewrote it, shortening the latter part of the script.[*]

If you try to watch the film as a standard mystery, fitting all of the clues

together to logically develop a hypothesis as to who the murderer might be, you find yourself continually frustrated by the narrative development .

I think everybody got very confused. It's a confusing book if you sit down and tear it apart. When you read it from page to page, it moves so beautifully that you don't care, but if you start tearing it apart to see what makes it tick, it comes unglued. Owen Taylor, I believe, was the name of the chauffeur. I was down on the set one day and Bogart came up and said, "Who killed Owen Taylor?" I said, "I don't know." We got hold of Faulkner and he said he didn't know, so they sent a wire to Chandler. He sent another wire back and said: "I don't know." In the book it is never explained who killed Owen Taylor, so there we were.

In writing your portion of the screenplay, did you have any concept in mind of the role of the private eye as an archetypal hero?

I don't think I dissected it that much. I was very much under the spell of Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, and I have written a few stories myself in that same vein. Something struck me. I liked it and I felt it, but I don't think I really analyzed it as I might do now, but I was a lot younger then. I just sort of accepted it.

Are there contributions you made to the characterization of Philip Marlowe which are distinct from Hawks'?

I don't know that I contributed too much to Marlowe, because I was taking directly from the book. This was the bible, and I wouldn't dream of changing it. I think that the characterization of Marlowe as done by Bogart and directed by Hawks was entirely their own. On the other hand, I think Bogart was ideal and, as far as I was concerned, he was the greatest actor that ever happened. I adored him. Actually, it was a joy to watch him on the set because he was stage trained. On a Hawks film nobody gets their pages until five minutes before they're going to shoot. Bogart would put on his horn-rims, go off in a corner, look at it, and then he'd come back on the set and they'd run through it a couple of times, and he'd have it right down, every bit of timing, and he'd go through about fourteen takes waiting for the other people to catch up to him.

I don't like to say this, because it sounds presumptuous, but Hawks and I kind of tuned in on the same channel with regard to the characters, and I think this is probably one reason that I worked with him so long. He was able to get out of me what he wanted because I had somewhat the same attitude towards the characters as he did.

There is a revisionist effort popular with such critics as Pauline Kael and Richard Corliss to consider the work of the screenwriter in contrast to the auteur theory, which postulates the director as the author of the film. When you look back on the movies that you wrote for Hawks, do you see them as Leigh Brackett films or Howard Hawks films or as collaborations?

It's a collaboration. The whole thing is a team effort. A writer cannot

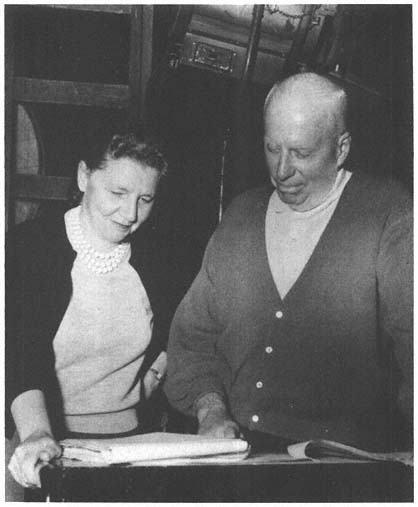

"Tuning in to the same channel": Leigh Brackett and director Howard Hawks at

work on Rio Bravo (Photo: Museum of Modern Art)

possibly, when he's writing a film, do exactly what he wants to do as when he's writing a novel. If I sit down to write a novel, I am God at my own typewriter, and there's nobody in between. But if I'm doing a screenplay, it has to be a compromise because there are so many things outside a writer's province. Hawks was also a producer, and he had so many things to think about that had nothing to do with the creative effort—with the story—like cost and budget and technical details that you must learn to integrate. You cannot possibly just go and say: "Well, I want to do it thus and such and so,"

because presently they say: "Thanks very much and goodbye." it just has to be that way.

You came out of the tradition of the pulp magazines, where you were allowed a degree of creative control. How did you react to having less control over your work in Hollywood?

I sort of went off into corners and wept a few times at things that made me very unhappy. I think the hardest thing about adapting to working with other people was that. Because I was a fiction writer primarily, and I was used to writing in a little room with the door shut, just myself and the type-writer—all of a sudden I'm sitting in this room with film people and I've got to talk ideas. God I froze. Everything I was about to say sounded so dreadful. It took me quite a few years to adapt and also to learn my craft, because I don't think there's anything better than screenwriting to teach you the construction of a story.

I was very poor on construction when I first began. If I could hit it right from the first word and go straight through, then it was great. If I didn't, I ended up with half-finished stories in which I had written myself into a box canyon and couldn't fight my way out. In film writing you get on overall conception of a story and then you go through these endless story conferences. Hawks used to walk in and he'd say: "I've been thinking . . ." My heart would go right down into my boots. Here we go: Start at the top of page one and go right through it again. But you still have to keep that concept. It's like building a wall. You've got the blocks, and you've got the wall all planned, and then somebody says: "I think we'll take this stone out of here and we'll put it over there. And we'll make this one a red one and that one a green one." You're still trying to keep the overall shape of the story, but you're changing the details. It took me a long time, but I finally learned how to do it. It was exhausting.

One of the observations gleaned from an auteur-oriented examination of Hawk's films is that certain sequences keep repeating themselves, being remade in different settings with different actors. For example, the scene in The Big Sleep where the gangster is in the house with Bogart and Bacall while his henchmen are waiting outside. Bogart throws him out and hawks cuts to a shot of the door being riddled with bullets. That scene is reshot in El Dorado where John Wayne throws a cowboy out of a saloon and Hawks again cuts to a shot of the door being riddled with bullets from the henchmen waiting outside. Your wrote the screenplay for El Dorado. Did you do that deliberately, or was that Hawks?

That was Hawks. I have been at swords' points with him many a time because I don't like doing a thing over again, and he does. I remember one day he and John Wayne and I were sitting in the office, and he said we'll do such and such a thing. I said: "But Howard, you did it in Rio Bravo . You don't want to do this over again." He said: "Why not?" And John Wayne,

all six feet four of him, looked down and said: "If it was good once it'll be just as good again." I know when I'm outgunned, so I did it. But I just don't like repeating myself. However, I'm wrong about half the time.

El Dorado is virtually a remake of Rio Bravo, with a certain reversal of characters . In Rio Bravo, John Wayne is the upstanding sheriff and Dean Martin is the drunken gunfighter . In El Dorado John Wayne is the upstanding gunfighter and Robert Mitchum is the drunken sheriff . Why bother to make El Dorado when you had already made the definitive version of that story in Rio Bravo?

I wrote the best script I have ever written and Howard liked it, the studio liked it, Wayne liked it, and I was delighted. We didn't make it, because he decided to go back and do Rio Bravo over again. It could have been called The Son of Rio Bravo Rides Again . I wasn't happy, but I did the best I could to make it a little different. Amazingly enough, very few people, except film buffs, caught the resemblance. I thought, my god! The critics will clobber us, because we did this before, practically word for word. The scene where Jimmy Caan threw himself in front of the horses we had done in Rio Bravo, but it was cut out of the final print because the final print was overlength. I said: "Howard, you can't do that. Warner Brothers owns it." He said: "All right, I'll buy the rights back." So what can you do?

Of the two, Rio Bravo was infinitely better cast . Arthur Hunnicutt in El Dorado played what was essentially Walter Brennan in Rio Bravo, but his performance is in no way comparable . Brennan as "Stumpy" is one of my favorite film performances, and was certainly of Oscar calibre .

He deserved it. Arthur Hunnicutt is a nice man and a good actor, but he's not Walter Brennan. When we began working on Rio Bravo we were harking back to To Have and Have Not [also directed by Hawks, 1944], in which Brennan played a similar character. We took him off a boat and put him in a Western town. That didn't work too well, so it got gradually worked around, after about the fourth or fifth version of the screenplay. Howard has a certain number of things that are very important to him. Usually the relationship between two men is a love story between two men. The obligations of friendship—what a friend is required to do for a friend. I suppose if you look at it, there are great resemblances.

You also helped write the screenplay for Hawks' last film, Rio Lobo. There are sequences in it which are in his earlier pictures, so for a third time he reshot some of the same scenes .

I didn't do the original script. Hawks asked me to work on it in the beginning, but I said: "I'm sorry. We're leaving for a trip around the world tomorrow, so I can't." Instead he got Burton Wohl. I came in on it, actually, as a rewrite. Not being used to working with Hawks, Mr. Wohl had some difficulty adjusting. Howard drives writers right up the wall. He will throw you a whole bunch of stuff and say: "This is what I want." And then he goes away

and you don't see him again for weeks. He leaves it to you to fit it all together and make a story out of it. He doesn't go into all the ramifications of motivation—that's what he's paying you for.

Writers get very confused. Most of what I did on Rio Lobo was to try and patch over the holes. If these people ride into town and go into the saloon and shoot somebody—why? Nobody knows. And you try to figure out why. So that was mostly what I did. I was unhappy that he went back to the same old ending of the trade, because it was done beautifully in Rio Bravo and done over again in El Dorado . As Johnny Woodcock, the film editor, said, "We get better at this every time."

I'd like to get your observations on working with John Wayne . When I interviewed [director] Mark Rydell at the time he was promoting Cinderella Liberty [1973], he shared an anecdote with me about the filming of The Cowboys [1972] . He noticed that, on the set Wayne became very friendly with Roscoe Lee Browne, who is a man of impeccable taste and sophistication. They would sit around quoting poetry to each other and sharing their love for the classics. Did you find any unexpected qualities in Wayne's personality?

I don't think I ever quite came across that facet of his personality. I didn't ever work too closely with him. On Hatari! they went to Africa for a number of months and came back with magnificent animal footage, but there was no people story. Of course, I had written five scripts, but none of them was the script, as it were. That was the year that Howard was not buying any story. He didn't want plot; he just wanted scenes. So I wrote ahead of the camera.

Normally, once a picture starts shooting, a writer's job is finished. He doesn't have anything to do with the people. But I was on the set with Duke, and to a certain extent, for a short while, on El Dorado as well. He is a highly professional actor. He is quite without [an arrogant] side. He's been the number one box office star for God knows how many years, but he doesn't come on that way. He's just there to do his job and do it as best he can.

I remember him working with the baby elephant in the scene at the end of Hatari!, where the critter gets on the bed and it crashes down. They tried about eighteen takes, and he said: "He's doing it right, I'm not." The elephant had his cues down perfectly, but it was Duke who was blowing it. He's a much more complex person than people give him credit for being.

What do you think of the Westerns that have been made in recent years, coming after the classic work of Ford and Hawks?

Every once in a while I go back and read a little Western history, which is a marvelous corrective. Hollywood has created a totally mythic West, which never existed on land or sea. The whole concept of the hero, I think, began with Owen Wister's The Virginian, more or less. Ever since, there's been a too great feeding on oneself. When you utilize the same elements over and over, you finally begin to turn out excrement. The trouble is we've gotten away from what actually happened in the West. I wish that somebody would

just read a little history. The pioneers were hardworking people who worked like mad to scratch to stay in one place. It was a hard, cruel country out there. These were heroes in a different sense, because they fought however they could to hold onto what they had. They didn't worry about who drew first. They just went up from behind with a shotgun. The idea was: "Don't get killed yourself—kill him."

Of course, I like the Hollywood Western because it's fun, but I think that some people are taking it far too seriously, because they're not dissecting anything real to begin with.

From what you've said, it sounds as though it was a very lively atmosphere around the sets of the Hawks films, with his spontaneously creative working habits. It must have prepared you, then, for Robert Altman, who I understand also likes not to inform the cast as to what they'll be shooting the next day. In fact, many times he doesn't bother to worry about it himself. How were you brought into the project of writing the screenplay for The Long Goodbye?

Elliott Kastner, who was the executive producer, used to be my agent at MCA a long time ago and we're good friends. He remembered The Big Sleep and he wanted me to work on The Long Goodbye . He set the deal with United Artists, and they had a commitment for a film with Elliott Gould, so either you take Elliott Gould or you don't make the film. Elliott Gould was not exactly my idea of Philip Marlowe, but anyway there we were. Also, as far as the story was concerned, time had gone by—it was twenty-odd years since the novel was written, and the private eye had become a cliché. It had become funny. You had to watch out what you were doing. If you had Humphrey Bogart at the same age that he was when he did The Big Sleep, he wouldn't do it the same way. Also, we were faced with a technical problem of this enormous book, which was the longest one Chandler ever wrote. It's tremendously involuted and convoluted. If you did it the way he wrote it, you would have a five-hour film.

I worked with another director who was on it before, Brian G. Hutton. He had a brilliant idea which just didn't work, and we wrote ourselves into a blind alley on that. It was a technical problem of plotting—the heavy had planned this whole thing from the start. So what you had was a prearranged thing where everybody sort of got up out of several boxes and did and said exactly what they had to do and say in order to get you where you had to be. It was very contrived and didn't work. Brian had to leave because he had another commitment, so when Altman came onto it I went over to London for a week. He was cutting Images [1972], which was a magnificent film—beautiful, powerful. We conferred about ten o'clock in the morning and yakked all day, and I went back to the hotel and typed all the notes and went back the next day. In a week we had it all worked out. He was a joy to work with. He had a very keen story mind.

Mark Rydell played the character Marty Augustine in The Long Goodbye.

He is an old friend of Altman's, so I imagine they were able to work together more easily. Rydell claimed that he knew intuitively what Altman' s conception of the movie was, which many critics, as well as many members of the audience, missed—the satirization of the genre of the private-eye film, by placing the conventions of the forties in direct conflict with the realities of the seventies. Were you aware of Altman' s intentions during your story conferences?

Actually, I was more aware of the construction of the thing, which is more my department. What he does with it after he gets the script is something else again. I don't think I was quite as aware of the satire as I became later.

Jay Cocks of Time magazine accused Altman of mocking "an achievement to which at his best he could only aspire," because he tried to demythologize Philip Marlowe. I imagine a lot of critics who are in their forties and fifties now grew up with the myth of Bogart as Marlowe, and hated to see the end of the film in which Marlowe murders Terry Lennox with no remorse. In fact, after he commits the murder, he dances down the road whistling "Hooray for Hollywood!" You are responsible, to some degree, for helping to create and propagate that original myth with The Big Sleep. Then you turned around and helped to sabotage it in The Long Goodbye. Do you consider that a betrayal of your earlier values?

No. Actually the ending, where Marlowe commits the murder, was in the script before Altman came onto it. The ending of the book was totally inconclusive. You had built up a villain. You feel that Marlowe has been wounded in his most sensitive heart, as it were—he's trusted this man as his friend; the friend has betrayed him. What do you do? We said let's just face up to it. He kills him.

In the time that we made The Big Sleep you couldn't do that because of censorship, had you wanted to do it. We stuck very closely to Chandler's own estimate of Marlowe as a loser, so we made him a real loser—he loses everything. Here is the totally honest man in a dishonest world, and it suddenly rears up and kicks him in the face, and he says: "The hell with you." Bang! I don't know whether we were right to do it, but I don't regret having done it. It felt right at the time. This was the way it turned out.

What do you think of the conceptions and characterizations of Marlowe as portrayed in the other film versions of Chandler's novels?

I thought Murder My Sweet [1944] was a beautiful film. The others all had points of excellence and also points where they didn't quite come across. The experimental business of "I am a camera" in Lady in the Lake [1946] didn't work too well.

It has been said that Philip Marlowe was sort of the son of Sam Spade. As Chandler said: "Down these mean streets must go a man who is not himself mean." In other words, here is the knight in shining armor with a shabby trench coat and snap-brim felt hat. I think he is a universal folk hero who does not change down through the ages except in the detail of his accoutre-

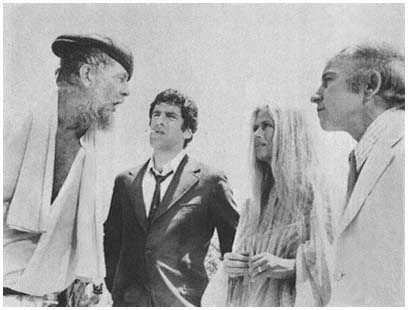

"A real loser": Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) with Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden, at

left), Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt), and Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) in the 1973

version of Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye . Leigh Brackett updated the

quintessential 1940s private-eye novel for director Robert Altman's film.

ments. He's not carrying a sword but a .32 automatic. The essential is that here is a man who is pure in heart, who is decent and honorable and cannot be bought—he is incorruptible. I think the concept was damn good, a very moral concept.

What did you think of Gould's performance, miscast as he was?

I thought he did a beautiful job. However, the thing about Elliott is that he isn't tough. His face is gentle, his eyes are kind, and he doesn't have that touch of cruelty that you associate with these characters.

With all of the disappointments that you've suffered—having your scripts revised without your approval to produce inferior versions of previous pictures—will you continue to write screenplays? Is there anything on the horizon that we can look forward to?

There's nothing definite at the moment. I have an original Western screenplay out and around, and I'm hopeful. It's a comedy. There are a number of things on the fire with television. As you know, the whole picture has changed out there very greatly in recent years. You grab what you can get. I wrote a script for "The Rockford Files" that was telecast last season.

But I greatly enjoy the work. It's a challenge. It's more technical than creative. What you have to be is a very good journeyman plumber and put the parts together. And then, if you can still inject a little bit of something worthwhile, you've done as much as can be expected.