PART THREE

LOCAL TIME AND THE ENCOUNTER WITH "HISTORY"

10

A New Order of Time

Church and State

The house they enter on the seventh day

Weans them from the breast of the mother marapu

The office they go to on the other days

Pushes them from the lap of the father marapu

—From a song of protest by pagan Kodi villagers

In the last three decades, a new order of time has made itself felt on the island of Sumba. Control by the Netherlands East Indies did not become a reality until the twentieth century, and the spread of education, the market economy, and political surveillance was constrained during the colonial period. The horizontal expansion of the Dutch empire stopped when the eastern islands were brought under effective political control, but the vertical penetration of the state and its calendars, schedules, and history into the more isolated areas became complete only after control passed into Indonesian hands.

The period since 1950 is designated in Kodi traditional couplets as the time of the "land of independence, the stones of electoral campaigns" (tana merdeka, watu kampanye ). Awareness of a new and different temporality during this period grew thanks to dramatic increases in the building of schools, the establishment of literacy programs for both adults and children, and an expanding bureaucracy that recruited many local people as civil servants. The articulation of the goals of the state as a state—that is, as an institution that imposes a particular organizational structure on its citizenry—is characteristic of Suharto's "New Order" and the ideological agenda of Golkar, the ruling party (Anderson 1990, 94-95, 117). The participatory, cultural "imagined community" of the nation was married to an older, corporate structure of the state, first formed during the period of the Dutch colonial administration. The period immediately following independence (1950-66) was concerned primarily with the idea of the nation, and efforts focused on fulfilling Sukarno's vision of a new revolutionary coalition; the period since 1966, however, has seen an increas-

ing emphasis on administrative coherence and discipline, with much deeper consequences for local notions of autonomy, cultural diversity, and temporality.

New definitions of cultural citizenship within the nation have tied the increasing penetration of the state to evangelical activity. Conversion to a world religion (here, Protestantism or Catholicism) has become a prerequisite for participation in the wider world of government, schools, and trade. Although the history of missionary efforts on the island began in the nineteenth century with an ill-fated Catholic outpost, their success came largely after other important social changes took place which made the new faith attractive.

The triumph of Christianity in Kodi is in fact linked, I argue, to the appeal of a progressive model of time, a view of "history" as a global and linear framework for comprehending the evolution of man and society. Instead of defining themselves in relation to a distant past of origins, and a cumulative accumulation of traditional value, Kodinese started to frame their actions and expectations in terms of a model of future progress and achievement. This change is ultimately what explains the new success of conversion campaigns and the waning influence of the traditional calendar.

Entering the "Bitter House": Stages of a Dialogue

Christian missionaries first came to Sumba from Germany and Holland with the hope of bringing isolated pagan peoples into the wider community of the Catholic or Protestant church. They began a dialogue with the Sumbanese that initially paralleled other exchanges with significant outside interlocutors—the sultanates of Sumbawa, Flores, and Java and Dutch colonial officials. An important difference soon emerged: the missionaries wanted something more than accommodation to their power through the payment of taxes, the observance of regulations, and the acceptance of an overarching power. They sought conversion, a change in internal attitudes and convictions. "We came to bring them a totally new understanding of the spiritual world and a new way of acting toward it" explained a former minister. But few people in Kodi were convinced of these "new understandings" until other changes gave them relevance. Telling them of an omnipotent God, inescapable sin, and the promise of redemption did not make sense until the experience of secular power and material inequalities brought such notions home.

When the dialogue began, each side Saw the encounter in fundamentally different ways. The Christian and Catholic missionaries believed that they were negotiating a meeting of two competing sets of gods. This

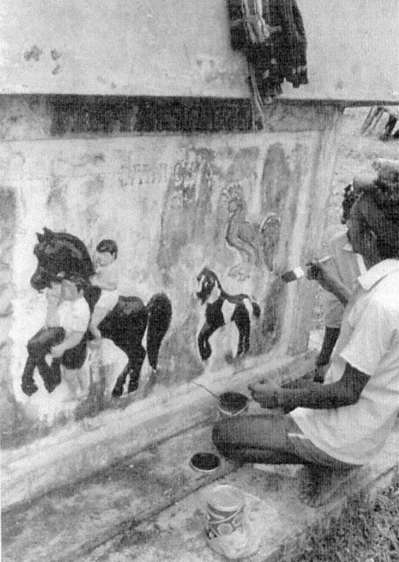

Ra Honggoro's tomb is painted to highlight images recalling his named horse

and dog, at the same time that his widow and most of his descendants have left

the marapu cult to convert to Christianity. 1988. Photograph by Laura Whitney.

perception is reflected in the title of a book, Marapu und Karitu , written by German Catholic missionaries about their experiences and describing mission activities as the meeting of local deities (marapu ) and Christ (pronounced karitu in the Sumbanese fashion). A response to directives issued by the national government, evangelization went hand in hand with development, so "teaching them about Christ was also teaching them about the modern world." The "understanding" the missionaries brought was an expanded world vision in which lineage ancestors and spirits of named locales in Kodi would begin to seem parochial.

From a Kodi perspective, the theology of the first missionaries was a mystery, and what could be identified and used to define them was not a difference in ideas but a difference in practices. Members of the new faith were called "people who go into their cult house on the seventh day [Sunday]" (tou tama urea lodo padu ) and observe prohibitions on noise-making and sacrifices on a weekly cycle. It was the ritual temporality of the first Christians—the way they demarcated sacred time—that set them apart from their fellows. Given the centrality of the regulation of time in the Kodi traditional system, this perception is not surprising.

The contrast in temporality marked the first stage of a process of conceptual reorientation, which shifted the notion of "religion" from one defined in terms of practices to one articulated as a system of beliefs. Indigenous worship of marapu was defined through traditional practices and rules of ritual procedure; only later did it become more self-conscious and concerned with doctrine. The terms of the dialogue changed in three separate historical moments: during the initial evangelical activity (late nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth), during a period of retrenchment and controversy in the newly formed churches in the 1950s, and when new debates cropped up in the 1980s.

The first dialogue, carried on during the period of the first conversions, focused on contrasts in ritual practice and the slow discovery of what actions were considered "un-Christian" by the Dutch and German missionaries. When control of the Sumbanese Protestant church passed into local hands, the problem of what was "un-Christian" was rephrased in definitional debates about the meanings of "paganism" "custom" and "culture."

The second dialogue, which began after independence, was formulated in response to a notion of religion presented by the Indonesian state. Religious tolerance under the principles of Panca Sila ideology was applied only to those systems that qualified as agama . In effect, this meant monotheistic world traditions that could document their practices with reference to an authoritative text. Embodied in the Sanskrit word was the

idea of a rich and foreign civilization with a tradition of learning and sophistication associated first with Hinduism, then with Islam and Christianity. Islam was in fact the clearest model, but Indonesia's early leaders, fearing the political power of Islamic fundamentalism, chose to specify religion as a "belief in one God" (Ind. bertuhan ), thus skillfully allowing for religious diversity in a nation whose population was predominantly Moslem. The minority religions of small pagan populations were excluded from this category:

Implicit in the concept of agama are notions of progress, modernization, and adherence to nationalist goals. Populations regarded as ignorant, backward, or indifferent to the nationalist vision are people who de facto lack a religion. Agarna is the dividing line that sets off the mass of peasants and urban dwellers, on the one side, from small traditional communities (weakly integrated into the national economic and political system), on the other.

(Atkinson 1987, 177)

On Sumba, the size and relative isolation of a large pagan population softened the initial impact of government policies to encourage conversion among those who "did not yet have a religion" (Ind. belum beragama ). Sumbanese did, however, think about the new category of "religion" and reexamine earlier practices, applying new notions of moral discipline, community values, and the ethical distinction between good and evil. Many wondered whether the presence of a Creator figure qualified their belief system as monotheistic and began to search for the "underlying principles" of the metaphoric imagery of ritual language. The rhetoric of nation building and New Order pressures for ideological uniformity put some pagans at risk. As peoples who appeared to reject the authority of both church and state, some were suspected of having communist leanings. In order to defend their ancestral system and to understand it better, a number of Kodi tried to articulate its tenets in terms of the new vocabulary of doctrine and precept, creating written accounts of dogmas to constitute a parallel system on the model of, but in contrast to, the Christian Bible.

These new forms of reflexivity and self-awareness resulted in both an increase in conversions and a retrenchment of traditionalists. It transformed the nature of indigenous conceptual systems even in the absence of a shift to an alien faith, since it permitted Sumbanese thinkers to build a new world of relationships between ideas and actions within the old house of ancestral custom.

The third dialogue, that of the 1980s involving a reevaluation of church

policy, was a response to continuing religious conservatism. Local leaders of the Protestant and Catholic communities wondered why they remained minorities in a society that in 1980 was still officially 80 percent pagan. New accommodations were made to allow for a return to the church after committing sins such as polygamy or sacrificing to the marapu . At the same time, word spread that the special "sixth column" on government census cards would no longer be an option in the 1990 census. Thus far, in addition to the five officially recognized religions of Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, local clerks had included a slot for agama marapu . Now, under increasing pressure to modernize, this would no longer be the case: an affiliation with a world religion, perhaps nominal at first, had become a requirement of full citizenship in the modern state. Church leaders were virtually assured a victory of numbers, but their prospective members insisted on a compensatory victory of content: they would convert, but only if conversion were redefined in a way that made the new faith more their own, a Kodi cocreation and not merely a foreign imposition. These incorporations of external authority into local social forms follow a pattern established in the distant past.

Finding "Religion" in the Indigenous System

The first task the foreign missionaries faced was to isolate the "religious" as a discrete category of experience from the wide range of loosely differentiated ritual, political, and economic practices of traditional society. At the beginning of this century, namely, the code of ceremonial etiquette and rules for interactions with the marapu also served to regulate marriage choices, the division of land, administrative prerogatives, and the exchange of livestock and cloth. Whenever a woman changed hands, whenever a promise was made, whenever a community shifted its residence, the ancestral spirits had to be informed and small offerings had to be made to them. They were the invisible witnesses of all important transactions, and they could hold the partners to their commitment by poisoning the very meat dedicated to them if such commitments were undertaken insincerely. The different domains of social life were so bound together that failure to follow the proper procedures in one—the performance of a burial rite, say—would have repercussions in another—failure of the crops, illness in the house, or destruction by fire or lightning. There was no separate "secular" realm where transactions could be carried out without summoning the ancestral spirits. Missionaries themselves constructed this division and so, unwittingly, became agents of secularization.

The relationship between the human community and the invisible

world of the marapu was one of complementarity and balance. Exchanges with spirit entities were made in order to receive tangible rewards and to satisfy cultural ideas of completeness. In the dualistic terms familiar to peoples of the eastern end of the archipelago, this was the principle of pa panggapango , the idea that things were "paired" and had a "twofold" nature—meaning that the opposition of inside and outside, male and female, cultural order and natural vitality, was inherent to any dynamic process. The oppositions were always shifting and unresolved; often they were not totally discrete categories but parts of a single whole. Major deities, addressed with a double name such as "Elder Mother, Ancient Father" or "Mother of the Land, Father of the Rivers," epitomized the synthesis of male and female and were portrayed as protective parents who defended and nourished their living offspring. The high degree of integration between elements in the system reinforced the dependency of each sphere on another and made religion difficult to isolate from the social and spatial totality of life.

Rules and procedures for ritual practice were clearly articulated, but abstract ideas about the structure of the cosmos and its attributes were hard to find. The Kodi describe the universe as made up of six levels of land and seven levels of sky (nomo ndani cana, pitu ndani awango ), but the spirits are not arranged on separate levels of this structure. The "highest deities" those who lived in the sky, were higher in altitude but not necessarily in status than those who lived in the ground. Relations of hierarchy and deference were expressed in an etiquette of address for speaking to the spirits. Only the less important spirits of the margin and periphery could be called on directly, while all of the higher deities had to be approached through spirit deputies and intermediaries, in a complex chain of communication that eventually led back to the Creator.

Foreign missionaries were intrigued by the fact that the Sumbanese did acknowledge a single maker and sustainer of human life. Yet they were somewhat puzzled by the fact that "the one who made us and formed us" (amawolo amarawi ) was portrayed in Kodi as both male and female, a mother who bound the hair at the forelock and a father who smelted the skull at the crown (inya wolo hungga, bapa rawi lindu ). Far from being an omnipotent and punitive God, whose divine justice was felt in the world, this Creator figure was rather distant from the lives of human beings. Referred to as the "one whose namesake cannot be mentioned, whose name cannot be pronounced" (nja pa taki camo, nja pa numa ngara ), she/he could not be addressed directly in prayer; rather, a whole chain of intermediaries was needed to send a message. Minor entreaties and pleas had to be brought first to the local guardians of the garden

hamlet, then to the ancestors of the clan village, and finally, carried by sacrificial animals, they reached the upperworld.

Both a cosmology and a theodicy seemed to be absent. Despite elaborate narratives about the voyages of the ancestors or the history of a particular sacred object, the Kodi had no detailed vision of life in the upperworld or the origins of deities and spirits. When asked about such issues, most Kodi simply confessed that they did not know. A particular, partisan version of the past was passed down a descent line or transmitted along with certain valuables, but no more all-encompassing questions were asked. Familiar themes in Western religious discourse, such as the ultimate destination of the soul, the origin of the human race, and the underlying reasons for suffering (beyond case-by-case instances of a given spirit's anger) were also largely ignored in the otherwise rich body of oral traditions. Explanations were undertaken piecemeal in terms of the context at hand, instead of being formulated in the abstract language of religious doctrine or dogma. A primary concern was for ritual correctness rather than cosmological speculation. The proper procedures for making an offering, reciting a prayer, conducting a feast, or erecting a gravestone were the focus of discussion and debate, but there was little need to reflect on how they fit into a wider model of understanding.

Ritual specialists who performed divinations, songs, and oratory saw their task as repeating the "words of the ancestors" preserved in the paired couplets of traditional verse, not as devising their own interpretations. Even the oldest and most respected priests would assert that they were only "repeating the words of the forefathers, stretching out the speech of the ancestors." Their role was not to assert or describe the order of the universe but simply to reenact the cosmic system in ritual procedures where the truth of the sacred mysteries would become evident: "We are just the lips told to pronounce, we are only the mouths told to speak."

This attitude of humility and self-deprecation before the unknowable meant that spokesmen for the traditional system retreated into disclaimers whenever their system of worship was challenged. It would be culturally inappropriate to claim a full understanding of the workings of the marapu , so all they could do was stubbornly insist that a logic informed the rites dedicated to the ancestral deities but it lay beyond their grasp. No single practitioner was qualified to serve as a prophet of tradition, and doctrines were not formally articulated as in the Christian church.

Early Evangelization

The period of early evangelization in Kodi was marked by three stages: first, a great curiosity and eagerness to receive the blessings of the foreign

god; second, a growing awareness of difference and the gradual development of an idea of tolerance, when the new faith was allowed to operate in the separate sphere of government service; and third, a definition of the Christian and traditional systems in terms of a contrast in ritual practice, particularly with regard to the timing of worship and periods of prohibitions. These three stages formed the necessary preamble to the final period, when the dialogue between the Christian church and the indigenous system assumed greater importance and when we can discern the beginnings of a shift from a contrast in terms of practices to a contrast in terms of belief.

Christianity came to Kodi with two different faces: that of the stern, Calvinist creed of the Dutch Reformed Church (Zending der Gereformeerde Kerken) and that of the more elaborately ritualized Catholic mission, made up primarily of German and Dutch priests of the Societas Verbi Divini. The Catholics built the first permanent structures in West Sumba when they established a Jesuit mission in 1889 at Pakamandara, in the domain of Laura—a site chosen because of its proximity to the northern port of Wai Kalo and the availability of fine limestone for building. Upon arrival, the two German priests in charge, together with their staff of seven young men from Flores, placed themselves under the protection of the ruler of Laura, who had once visited Java and was willing to welcome them (Haripranata 1984, 121). The ruler was asked to explain the benefits of baptism to his people, and within a short while hundreds of people showed up to be baptized. The priests immediately christened 610 young children, but told adults they should wait to receive religious instruction before entering the church. One of the two priests, Father Schweiz, reported that the sacrament of baptism was enthusiastically received by the parents, "who held their children in front of us with such happy faces, as if they were about to be given gold valuables and fine jewels" (Haripranata 1984, 123). People were also eager for their children to attend school, and soon twenty-seven students from prominent families were allowed to begin their studies.

In 1891, Father Schweiz surveyed the area and reported: "I went on a trip into the interior, traveling to the domain of Kodi, about a day's ride by horse to the west of Laura. Kodi is a very beautiful and fertile land, with a large population. I hope that many of them will want to join the church, since they received me well. I asked that the sons of noble families be sent to our school, but who knows if they will comply with this request" (Haripranata 1984, 131).[1] His optimism did not endure, however. Ten

years after it was established, the mission fell prey to horse thieves, arson, and petty larceny. Conditions were considered too difficult to send nuns or supplies on a regular basis, and finally the political instability in the area caused church authorities to close down the mission. Very few adults had been baptized, and school administrators noted that as soon as boys reached adolescence they were taken back by their families, leaving no mature converts to build the Catholic community (Haripranata 1984, 172-73). In 1898, the mission in Laura was disbanded and its staff left the island.

In 1907, D. K. Wielenga, a Protestant missionary who had been working in East Sumba for three years, traveled to West Sumba and decided to use the abandoned buildings at Pakamandara for his own evangelical activities. He opened up a Protestant school, bringing Christian Indonesians from other islands (Roti, Savu, or Ambon) as teachers to educate the sons of local rulers and noblemen. Consistent with Dutch colonial policy at the time, the school was established to train future administrators, and admission was contingent on a hereditary claim to rank. Soon the Dutch Reformed Church built other elementary schools in neighboring districts. By 1913 there were seventy Protestant village schools and four secondary schools, as well as a "theological seminary" near the original mission station in Karuni, where promising students could continue their studies.

Competition between the two churches developed as soon as members of the Societas Verbi Divini asked to return to the earlier mission site. The Dutch controller Couvreur advised against the move, saying the presence of two foreign faiths would simply confuse the local population, making it more difficult to convert them (Haripranata 1984, 205). Invoking the 1913 "Flores-Sumba Contract" he reminded Catholic authorities of an earlier agreement by which the colonial government gave Flores to the Catholic church and Sumba to the Protestants (Luckas n.d., 18). The Catholics, however, having already established themselves soundly on Flores, now pleaded that their history of mission activity on Sumba was as long as that of the Protestant Reformed church and that they should be able to serve those converts left behind upon the Jesuits' departure. In 1929, the government finally relented, permitting the establishment of

Catholic schools and hospitals on the island but maintaining the policy that only the Protestants would receive government subsidies and the official stamp Of approval, since they were seen as operating within the parameters of a privileged relation to the state (Webb 1986, 51; Van den End 1987, 43-44).

By that time, an alternative pattern of evangelization had been established by the Dutch Reformed Church. Recognizing that many Sumbanese wanted to gain literacy and knowledge about the world, though not necessarily to become Christians, the Protestants organized their church using an extensive network of native evangelists (guru injil ), at first from other islands but soon largely Sumbanese, who carried the Malay Bible into distant regions. The evangelists were given literacy training, a small salary, and a prestigious link to the authority of the church. Their duties were to lead prayer and translate sections from Malay into the vernacular.

The Dutch Reformed Church placed great importance on language as a medium of conversion. The missionary-linguist Louis Onvlee published translations of the New Testament in Kambera and Weyewa, the two largest Sumbanese languages. But no foreign missionary, Protestant or Catholic, ever achieved proficiency in the Kodi language. Evangelists thus had much greater influence and autonomy in Kodi than in. many other areas, and they enjoyed considerable freedom to reinterpret the foreign message in Kodi terms—a point of attraction for many. The first Christian convert in Kodi Bokol was Yohannes Loghe Mete of Kory, a tall, distinguished older man who was still alive when I first came to Sumba. He was baptized in 1919, after having completed his studies at a Christian elementary school at the age of fifteen or sixteen. He was attracted to the church as a doorway to apprehend a much wider world:

At first we cannot really say that we were called by Jesus or by God, because we didn't really know what those things meant. I had gone to school to learn to read, to find out about how things were in countries across the seas. I became a Christian because my teachers needed help to translate hymns into Kodi and to explain the Bible stories to people here. They were very strict with all of us. I couldn't eat the meat at traditional feasts because it had been dedicated to the marapu . I had to tell people that polygamy was a sin. I worked as a village evangelist, going from one house to another to read the Gospels. People asked me if I wasn't afraid of the white foreigners, but I said no, I'm not afraid, they are the ones who can show us the path to move forward.

By the 1930s, two Kodi ministers had been ordained: Pendita Ndoda, a

descendant of Rato Mangilo in Tossi, and Pendita Kaha, a member of the village of Kaha Deta, Balaghar, guardian of the rites of bitter and bland in that area. Both had genealogical claims to positions of spiritual leadership but chose to throw in their lot with the new faith instead.

Two things marked the new Christian community: the respect accorded to the written word, which was treated as sacred, and the requirement to attend church services on Sundays. Literacy came to be seen as an attribute of Christianity, so conversion was expected of anyone who continued his studies to the secondary level or beyond. Those who remained in the villages and did not aspire to government service felt no call to convert. One old woman told me that she wanted her children and grandchildren to go to school and enter the church, but such a course was not appropriate for her: "If I held the Christian Bible in my hand, I would not be able to read it. I cannot even understand the Malay prayers. So what use does it have for me?" Mastery of Malay and reading skills were seen as prerequisites for ritual correctness in the new Christian system.

The church took the name of the new unit of temporality that it introduced: the week. The "house that one enters on the seventh day" (urea pa tama lodo pitu ) was associated with a series of religious prohibitions that seemed to parallel the prohibitions of the "bitter months" in the Sumbanese calendar: it was not proper to sing or dance on Sundays, frivolous activities and feasting were frowned upon, and the violation of these taboos was shrouded with threats of supernatural sanctions. Just as calling young rice seedlings and immature corn ears "bitter" was a way of setting them apart and designating them as inedible until the proper ceremony had been performed, in a similar fashion the Christian church regularly set apart a day for worship, and the interval between these worship days was also the unit used for reckoning market days and government-announced events. So the church became "the house of the bitter day" or simply "the bitter house" (uma padu ).

This label did not in itself indicate hostility or suspicion of the church; it simply acknowledged a different demarcation of sacred time. The Christian church was assumed to parallel the indigenous system in expressing its truths and mysteries indirectly, through a series of procedures that gave followers methods for communicating with and appeasing the higher powers. The two were presented as alternate versions of the same sort of conceptual system—an approach consistent with Kodi understandings of the cultural variation that existed between different districts of the island.

In the 1930s, the Catholic church returned to rebuild the mission in Laura. All of the nine hundred children who had been baptized by the nineteenth-century Jesuits had returned to their traditional system of

spirit worship, and many were now polygamously married. They could be traced only by the names they had been given on the basis of their day of baptism. On a Monday in 1889, for example, Father Schweiz had christened twenty boys as lgnatius, on Tuesday he called thirty girls Maria, and on Wednesday he called thirty others Theresia and Franziskus (May, Mispagel, and Pfister 1982, 23). The coming of the foreign faith to Sumba was presented as a new temporal cycle, a round not only of Sundays but also of saints and children named after the saints. In Sumbanese languages, the days of the week are now designated with numbers (Monday is lodo ihya , "day one"; Tuesday, lodo duyo , "day two"). Giving a personal name ("Domingus") to a day of the week (Ind. hari minggu ) only perpetuated the idea that children in Western countries were named after the days of the week. Indeed, the saints' calendar does locate names on a time line, and this time line is then linked to celebrations of saints' days and religious festivities, so their view was not entirely false.

The Catholic church came to be designated quite often as simply "the mission" (missi ). To recruit the early lapsed "Catholics" back into the church, a new temporal cycle of celebrations was established, and everyone was invited to attend. Huge festivities at Christmas and Easter, accompanied by traditional singing and dancing, became a hallmark of the Catholic mission. Collective ritual and dramatic spectacles attracted an audience, but these "entertainments" did not immediately effect conversion. A more powerful attraction came from the extension of social services—hospitals and schools—built by the mission with generous funds from Germany. Gifted Catholic students obtained scholarships, first to finish high school, then to study overseas, often with the express hope that a few of them would discover a vocation in the priesthood.[2] By 1936, two large hospitals had been built, one in Weetabula, Laura, and the second in Kodi, in a garden hamlet called Homba Karipit. In 1980, eleven Catholic schools were in existence, including a secondary school in Homba Karipit, and over thirty Protestant ones.

The several hundred employees of the schools and clinics were not formally required to convert, but most of them did, partly out of gratitude for the help they had received. "The mission is a good older brother" one convert explained to me; "my family could never have helped me so much

to get into a job where I would wear the long pants of a civil servant." As a result, Catholics, who made up 6 percent of the population in 1980, were largely concentrated in pockets close to the mission itself. Those who lived at a greater distance had generally received their education under the auspices of the Catholic church and sent their children to board at the mission so that they could meet suitable candidates for marriage.

The First Dialogue with the Church

The first period of dialogue with the Christian church, in both its Protestant and Catholic manifestations, was marked by the gradual emergence of points of difference, points of conflict, and points of convergence vis-à-vis the indigenous system. As Christian concepts of true "religion" became more salient, local traditionalists began to speak to these concerns in their own formulations of marapu practice. Joining the Christian community or remaining outside it were alternative social strategies that defined one's relation to the powerful forces whose authority was represented by the church. The "bitter house" belonged to the "stranger mother and foreign father" (inya dawa, bapa ndimya ) who commanded from across the seas and told its followers how to act. Leaders of the local population differed on whether the new faith and the older system were basically complementary or antithetical.

The question was first articulated with regard to the definition of church membership. The church was the first voluntary organization that most people had ever encountered, and so there was initial ambiguity about whether baptism was enough to define a Christian, or whether compliance with the rules and regular participation in church ritual was necessary as well. Since many of the first converts were schoolchildren, baptism was often misrepresented as a prerequisite for school attendance. Indeed, few people joined the church unless they had already made a commitment to schooling, government service, and relations with the outside world.

The key symbols of the Christian world were the book and pen, instruments to record messages and communicate them to people far away. The Christian Bible could be carried far from home, and the Christian God could be prayed to for protection even when it was not possible to visit the traditional village altars of rock and tree. Worshippers of the local spirits had to return each year to the site of ancestral stone graves, bringing the first fruits of the harvest and new entreaties for continued health and prosperity. They could ask a spirit companion to accompany them in a particular journey, but they could not bring the full protection of their forefathers to Java for schooling, medical care, or trade. Christians, by

contrast, carried their altar with them, so to speak, in the Malay Bible, using it to enter another world, which ordered its worship schedule around the church gatherings on the seventh day.

Many traditional villagers who were not hostile to the church saw their own practices of spirit worship as operating in a socially and geographically separate sphere from that of the Dutch ministers. The Christian church extended the circle of ritually mediated interactions beyond the island to a wider world. In traditional practice, Kodinese who traveled outside their traditional domain made token invocations to the deities of the regions into which they ventured. In their first experiences of Dutch schools, hospitals, and local administration, many Kodi converts followed the same pattern: while the marapu kodi were worshipped in the ancestral village, the marapu dawa ("foreign gods") were invoked on the foreign terrain of government offices.

Christianity and the Critique of Colonialism

In 1942, the Japanese army occupied Sumba and deported all Dutch ministers and their families to internment camps. Religious teaching was forbidden in schools (even those run by the Protestant and Catholic churches), and religious meetings were banned, with Sunday becoming an ordinary workday. Many village evangelists and early converts were suspected of being Dutch sympathizers. One Protestant church leader, Pendita H. Mbai, was arrested and apparently executed in 1944 (Webb 1986, 95). The churches once linked to the apparently omnipotent Netherlands East Indies and prestigious European culture suffered a heavy blow.

In 1945, the Zending staff returned to their congregations on Sumba, but the growing struggle for independence aroused a new cynicism concerning Dutch power and Dutch teachings. A derisive little verse in Malay reflected these feelings:

The Dutch have the Bible | Belanda punya Bijbel |

We have the land | Kita punya tanah |

[But if] we stick to the Bible | Kita pegang Bijbel |

The Dutch will stick to the land | Belanda pegang tanah[3] |

In other words, conversion represented a capitulation to Dutch authority,

and so long as the Sumbanese embraced their colonial masters' faith the Dutch would continue to exert their dominance over colonial subjects.

In 1946, Sumbanese converts left the Dutch Calvinist mission to form the Independent Church of Sumba (Gereja Kristen Sumba). They sought financial assistance from America and Australia rather than Holland, rebuking certain Dutch ministers for showing a "colonial mentality" toward native-born preachers (Webb 1986, 121). The leadership of the new church held its first synod at Payeti, Waingapu, opening the floor to a series of discussions about how to give the new faith a more Sumbanese flavor to speed up the conversion of the village population. Christian leaders thus allied themselves with the nationalist struggle for independence, thereby assuring the Independent Church of Sumba an important role in the government of the newly formed Indonesian state.

Beginnings of Conflict Between the Church and Local Practice

Conflict emerged in the restructured Independent church when the church leadership moved to expand its authority over the lives of its converts— this in a political climate already strongly influenced by Sukarno's vision of national culture and intense ideological debate at the state level. The specific point of contention was burial of the dead and, tied to that, the destination of the soul after death. For Christians, death was an immediate point of transition, the instant when an individual's soul was united with God and severed from the living. For Sumbanese, however, the dead continue to be enmeshed in social relations, growing in a sense even more powerful after death than before because of their ability to enforce supernatural sanctions and make demands on their descendants.

The church initially tolerated burials in the ancestral villages but discouraged communication with the dead through divination. Since dead parents and grandparents seemed to use the diviners only to demand new stone graves and the fulfillment of past ceremonial obligations, their requests were in direct violation of Christian practice. Once a temporary church structure had been erected in the district capital of Bondo Kodi, some land was set aside to serve as the consecrated burial ground for converts. Schoolchildren were among the first to be buried there, as well as some older people who chose the site (according to local gossip) in order to avoid the high costs of sponsoring a stone-dragging ceremony to erect a megalithic tomb in their own village. Yet as the number of bodies resting beside the small Protestant church grew, traditional diviners began to receive messages that some of the souls of the dead were unhappy there.

In the early 1950s, those dead souls whose family members had erected impressive stone graves now asked to be transferred to those socially more prestigious structures. Recurrent illnesses and hardships were explained by local ritual practitioners as resulting from the failure to bury the dead in the appropriate traditional manner. Soon the whole lineage and extended kin network began to mobilize for the transfer. Not only the bones of those buried on consecrated Christian ground would be moved, but also those of many younger wives, children, or poor relatives who had received initial burial in the garden hamlets before stone graves were ready for them. Many Sumbanese, it seemed, saw a Christian grave as only a temporary resting place before an appropriate ancestral site was ready.

To the church leadership, such a move was unacceptable. They claimed persons committed to Christianity were being "stolen back" into paganism after their deaths. The church also refused to accept the evidence of traditional divination, in which the spirits concerned were questioned through the medium of a sacred spear and made to reply at the base of the central house pillar. Communications from the invisible world were listened to more attentively by local government officials, who sought to avoid conflict by proposing a new use for the disputed land. They suggested erecting a government office and desacralizing the whole area.

The church firmly refused this plan. In 1952, after a long and tumultuous debate about the value of the church versus the importance of traditional obligations, a whole group of early converts seceded from the Christian community. Repudiating church rules, they insisted on returning the bones of their kinsmen to the ancestral village. The church leadership immediately banned them from attending further services and labeled them apostates, betrayers of the true faith (Ind. murtad ). The division established at this time between those who had chosen the church and those who rejected it was to become very influential in molding the shifting concepts of church membership: did simple adherence to a series of practices (such as attendance at services or reading from the Bible) suffice, or was a strong commitment to the ideas and principles underlying the belief system necessary? Through conflicts over such issues as burial, marriage, and feasting, differences in doctrine and wider interpretations of the universe began to emerge.

Other discrepancies between church teaching and traditional practice were less dramatic. Polygamy was the most common reason for someone to be suspended from church membership and forbidden from taking communion. The strategy of early evangelization had been to focus on local leaders and important families, encouraging them to draw in their friends and relatives for large group baptisms. Polygamy, although prac-

ticed by only 10 to 15 percent of Kodi men, was the mark of a prominent social figure. As a consequence, the rate of polygamy after a generation or so of Protestant evangelizing was actually higher among baptized Christians than among the unconverted. The church, while continuing to condemn the practice, allowed the guilty husbands to continue to attend Sunday worship services but not to take communion. Their many wives and children, however, were still welcomed to drink the blood and eat the body of Christ.

When the Catholic mission was established in Homba Karipit in the 1930s, the German priests were stricter than the Dutch ministers had been, barring both men and women from the communion table if they were polygamously married. In the 1980s, a reevaluation of such rules by both churches allowed for a final forgiving of the "sin of love" (Ind. dosa cinta ) for those older men, perhaps close to death, who agree not to marry again. Many prominent elders were brought into the Christian community by this leniency, but it understandably weakened the battle against polygamy. Virtually all men who took extra wives now hope to be forgiven before they die.

Participation at feasts, curing ceremonies, and divinations, though initially condemned by the leadership of both churches, was later accommodated under the rubric of family and community obligations. The early Dutch missionaries, to discourage attendance at feasts with a religious purpose, forbade their converts from eating meat dedicated to the marapu spirits. But in fact, almost no ritual killing of pigs and buffalo—such as for marriages, funerals, and naming ceremonies—occurred without the protection of the marapu being invoked. Christian converts, many of them important people who relished the honors conferred on them by active participation in the ceremonial system, objected that the church was in effect prohibiting them from eating any meat at all. Within a few years, this restriction was revised to a rule that prayers of consecration could not be pronounced by anyone who called himself a Christian. The rule was absurdly easy to follow, since almost all ceremonial ritual speech was recited by traditional specialists: the emphasis on message bearers and mediated communication with the spirits in the indigenous system meant that no man was allowed to be priest in his own house.

The last regulation also raised the question of what criteria distinguished a Christian ceremony from a marapu rite, particularly in light of the increasingly common practice of holding family rituals that included elements of both systems: a Bible reading and Christian blessing in Malay, followed by an invocation in Kodi ritual language by a traditional elder. A compromise was reached by dedicating one share of the sacrificial feast

to the marapu and another to the Christian God, then dividing it among the guests according to their religious preference. When policemen or government soldiers from other islands were present, Islamic prayers and sacrifices were also included. The local church leadership finally concluded that it was best to tolerate such "feasts of syncretism"; after all, they provided a forum for people of different persuasions to hear the Christian message and benefit from it.

Christian prayer meetings (Ind. pembacaan ) and "thanksgiving celebrations" (Ind. pengucapan syukur ) were often performed on the same occasions that traditionally had required the mediation of marapu spirits: at times of illness, transition (marriage, a shift in residence, or adoption of new lineage members), or hardship (after a fire, lightning bolt, or crop failure). As responses to a need for spiritual counsel and assistance, they followed the same pattern as nightlong marapu ceremonies: first the reasons for the gathering were explained, followed by the dedication of the animals to be slaughtered and the distribution and consumption of food. The most marked differences were in the languages used—biblical Malay versus traditional ritual speech—and the replacement of the sacred authority of the central house post with the portable gospel. There was also an important shift in the kinds of knowledge obtained from such encounters: whereas in traditional divination rites questions could be asked directly of the house post, with yes or no answers provided by whether the diviner's thumb reached its mark at the tip of the spear, the answers provided by the Bible were most enigmatic.

One informant told me that the major difference between Christian and marapu beliefs was that the marapu divination provided a much more specific explanation of human suffering and misfortune. Although Christian preachers, too, interpreted illness and calamities as signs of divine displeasure, they could not pinpoint either the precise cause or the proper procedures to appease the high God. Speculation could run wild as to the cause of the affliction, and there was no way for the human community to know if the ritual compensation offered was adequate. Marapu divinations, by contrast, allowed the victim to identify the angry spirits by name, to ascertain the precise chain of events that led to the misfortune, and to mediate the problem in ritual fashion.

Local religious teachers presented this moral and philosophical uncertainty as the consequences of original sin; humans had an obligation to repent and suffer, even without full knowledge of the reasons for this suffering, because of a burden of wrongdoing inherited from the ancestors. Since Dutch missionaries had internalized the notion of intrinsic human depravity and the resulting guilt, they constantly prayed for strength over

weakness, forgiveness for their bodily urges, and acceptance of their uncertain fate. When uttered by native-born religious teachers, these messages took on a somewhat different hue. In traditional Sumbanese understandings, the living are always laden down with obligations to perform ceremonies and arrange burials because of their duties to preceding generations; the idea of original sin was therefore interpreted as unfulfilled obligation to make it sound more compelling and convincing. The biblical story of Adam and Eve was recast in a Kodi idiom by village preachers, who spoke of the sin of "eating wrongly" in the Garden of Eden. A common consequence was the local perception that the sins of Adam and Eve lay not in eating the forbidden fruit of wisdom, but in failing to perform the necessary rites to "cool down" the land on which the apple tree stood, which would bring its fruit within the circle of ancestral protection so it could be eaten. The sons of Adam were condemned to suffer, in other words, not because of a thirst for knowledge, but because of disrespect for ritual boundaries and the category of bitter foods.

The distinction that the Kodi themselves make between the spirits associated with the inner, social world of ancestral authority and cultural control and the outer nature spirits of the wild was likewise reinterpreted in Christian terms. Early religious teachers, trying to convince the people to stop worshipping the invisible spirit powers, translated the local term marapu as setan . Although missionaries understood that marapu was in fact a very complex and multivalent term (Lambooy 1937), this gloss was the one most frequently used in village evangelizing, sometimes modified by the adjective kapir , "pagan." It identified all the members of the complex cosmological structure of Kodi with those malicious, capricious spirits at the periphery, similar to the Moslem jinn . When spokesmen for the traditional system protested that spirit beliefs provided a bulwark for community discipline and personal morality, some members of the church leadership began to distinguish between the "good marapu, " which they identified as the ancestors, and the "bad marapu " or setan , who were the autochthonous inhabitants of the forests and fields, seashore and ocean. The spirits of natural surroundings were seen as innately evil; those of the established village centers were presented as good. This application of a moralistic, ethical creed to an opposition that was rooted in complementary principles of control versus vitality proved difficult to uphold. Death and suffering, after all, were more often attributed to sanctions imposed by the ancestors than to the nefarious activities of the wild spirits. Likewise, the setan of the forests and fields could appear as companions on long journeys through wild lands, who provided medicines and magical powers in return for small sacrifices.

The critical Christian interpretation of marapu beliefs stigmatized the worship of a certain class of spirits—significantly, that class of spirits most often addressed in a private, individualistic context. Hence it allowed the church to take a relatively tolerant attitude toward those large-scale rituals that would tend to come to the attention of its leadership and condemn only smaller-scale interactions, which were harder to observe. Clearly, this was a policy of "turning a blind eye" in some directions in order to maintain the momentum of conversion on other fronts.

Christian prayers were often granted a magical efficacy similar to that of the ritual language associated with ancestral centers. They were used to ward off wild spirits and extend the protection of the social community to newly planted crops. The church thus played a parallel ritual role in "cooling the land," bringing it into the realm of cultural control. To the extent that church leaders were aware that they were borrowing the local idiom, they tried to identify the Christian message with the nurturing, protective care of the Great Mothers and Great Fathers of the ancestral centers, in opposition to the more volatile spirits of the outside. The blessings of ancestors was expressed in the metaphors of Sumbanese ritual speech as the flow of cooling waters. For this reason, Onvlee, the Dutch linguist who translated the gospel into the West Sumbanese language of Weyewa, called it li'li amaraingininga , the "cooling or salutary words."

Translating Sumbanese religious concepts was a challenging task because of the very different semantic weights assigned to words in the two systems. Writing about his difficulties in finding an appropriate gloss for the Christian concept of "the holy" Onvlee (1938) provides some insight into the thinking of the early Protestant leaders. Initially, he thought that "holiness" could be invoked with metaphorical representations of fertility, prosperity, and well-being, the "cool waters" that are beseeched in traditional prayers to cure fevers. But it was soon clear that "holiness" could just as easily be identified with the opposing pole: those "hot" spiritually charged objects in which divine power was supposed to dwell—sacred houses, village altars, or the divination pillar. The Sumbanese ritual oscillation between hot and cold, bitter and bland, is part of a cyclical movement of spiritual energies that simply does not fit well into Christian theology. It assumes that the bitter, hot, or prohibited nature of certain things is merely a transitory stage through which they must pass before they are brought inside the circle of ancestral control where these energies are harnessed to social tasks.

Onvlee's discussion of the possibilities he considered supports an interpretation of the early dialogue between the church and local spirit worshippers as one phrased in terms of practices rather than beliefs, and one

that privileged one temporality over another. His search for a parallel to the Christian concept of "holy" also led to terms that convey a sense of social distance from everyday life. The East Sumbanese term maliling , for instance, refers to the stipulations of respect and avoidance that must be observed between specific kin categories, such as father-in-law and daughter-in-law. However, in suggesting that the church could be described as a uma maliling , or "respected, separate house" he was unwittingly associating it with prohibitions and restrictions that made it suitable only for slaves. Many of the most sacred objects of the lineage are stored in the uma maliling : spirit drums, gold crests, heirloom water urns, and magical weapons obtained from overseas trade. These objects are seen as charged with so much spiritual energy that ordinary men are afraid to handle them. Taboos against defecating, swearing, or spitting in their presence mean that most people will not risk even living near to such objects. Only slaves are expendable enough to guard this sacred patrimony. Needless to say, it would hardly help the cause of village evangelization to define the church as a building so sacred that people would fear to gather inside it. The West Sumbanese term uma padu , the "bitter house" or "house of the seventh day" had something of the same sense but temporalized the associated prohibitions. Once a week, church members had to be set aside and appear as a community, but after this brief separation they could take part in daily life; the house of worship, in short, was not permanently dangerous. Onvlee's discussion underlines the irony that he himself observed in the process of translation: any word that seemed, in local terms, to define the Christian ritual center as important and sacred also set it apart from ordinary life and limited the number of converts who dared to cross its threshold.

Evangelization and Development: New Routines and Disciplines

After 1966, the New Order government asked foreign missionaries to devote most of their energies to "development" the main national priority. While evangelization could continue (and was encouraged, since the "Islam politics" of the new Indonesian regime was also fearful of Moslem fundamentalism), the emphasis was now on improving the standard of living of local peoples.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Protestant and Catholic churches were already quite distinct in Kodi perceptions. The Gereja Kristen Sumba was an independent organization, staffed entirely by native ministers, and received no more funding from the Dutch Reformed Church. Its ministers

became increasingly involved in politics, with two of them holding positions as elected representatives to the National Assembly (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat) and all called upon to assume a role in Golkar election campaigns. The Catholic leadership, still primarily German priests, were forbidden from political activity, but concentrated instead on building projects.

In Kodi, the most important of these projects were digging wells and providing pumps to make fresh water available to the population. In early 1980, the small river that ran through Kory, the largest and most densely populated administrative ward (desa ), went dry. The Catholic church built a large cement cistern to store rainwater, which it supplemented with clear water from an underground water source. In Bukambero, a solar-powered project at Payeti pumped an even larger cistern full of clean, fresh water, which villagers carried to their homes in buckets hung on the ends of long bamboo poles.

Water was a symbolically charged resource in an area where control of the rains and the seasons was once the supreme office. To get access to the underground rivers that they tapped, mission officials had to use a sacred source, which had lain untouched for generations. Special marapu ceremonies were held, and buffalo sacrifices were performed to make the area "bland" (pakabaya ), compensating local wild spirits so they would allow the nearby inhabitants to drink this water. In agreeing to perform these sacrifices, the mission tacitly accepted the authority of local priests who stated their necessity. But the priests also showed that new technology and labor could provide people with a critical resource, one that they could not obtain by simple prayers and offerings to their ancestors. The wells and pumps made a deep impression on the population of the wards nearest them, now almost half Catholic.

The Catholic mission's concern with hierarchy and decorum gave it a different character from that of the Protestants, with their stress on village evangelization. Practical skills were taught in Catholic schools as well as basic literacy. Boys received lessons in carpentry and masonry, and their labor was used to build new cathedrals at each mission. Girls learned cooking, sewing, and household hygiene. At the Homba Karipit mission, students lived in a dormitory; where they learned to set their routines by the clock, responding to bells that both announced the passage of each hour and corresponded to duty stations in a schedule of daily chores. The day was divided into segments, so that a girl would spend one hour helping in the out-patient clinic, another scrubbing floors in the kitchen, a third preparing food for guests, and a fourth mending sheets and bedding.

At the mission school, girls were prepared for roles as wives and moth-

ers, boys as wage laborers and mission employees; all the while their "spiritual guardians," the nuns and priests, convinced that temporal discipline would instill a sense of responsibility and orderliness, believed that they were encouraging young people to think for themselves and become free of the constraints of custom and tradition (Mispagel in May, Mispagel, and Pfister 1982, 91-92). Local people clearly perceived the mission as a training ground for Westernized gender roles and social habits. Kodi commentary on the value of the Catholic "housekeeping school" (sekolah rumah tangga ) and "craftshop" (sekolah tukang ) reflects this:

We send our daughters to Homba Karipit so they can learn to cook things that only Westerners eat, like bread and cookies. We send our sons so they can see how to build Western furniture—tables, chairs, cupboards, things that never existed in Kodi until they came. But now, in this time of foreign ways [pata dawa ], we need them. The girls learn to sew dresses and sarungs, and uniforms worn in schools and offices. These skills can bring in money later. Kodi women all learn to weave and tie ikat designs into thread. Women on Java and other islands learn to use a sewing machine and to make the national costume of sarung and kebaya, or the skirts and shirts of government bureaucrats. We say that the Catholic school teaches them "foreignness" [kejawaan ] so they can go other places.

The missionaries, aware of the commercial value of their teachings, commented that "a girl with a sewing machine brings in a bigger brideprice." The investment made by parents who paid tuition for this training was returned to them in water buffalo when their daughters married (Mispagel in May, Mispagel, and Pfister 1982, 91).

The missionaries valued promptness, cleanliness, hourly routines, and schedules as ends in themselves, not only as preconditions for wage-earning employment. Yet although the new "techniques of power" embodied in the regimentation of time, through its segmentation, seriation, synthesis, and totalization, were an attribute of missions and schools in Kodi, as they have been attributes of a great many other disciplinary institutions (Foucault 1977 , 139), they were not perceived as confinements and enclosures, but as ways of "opening up" their inhabitants to a wider world of historical forces.

Protestant schoolteachers learned a pedagogical practice that also emphasized timetables, homework, and examinations. Traditional training, by contrast, was through apprenticeship and an initiation. A small boy, for example, might accompany a famous ritual speaker, at first simply carrying the meat but later beginning to assist in sacrifices, to answer his

elder's orations with affirmations, and eventually to comment on them and even speak on his own behalf. His fitness for this final stage would be determined by divination. In both government and religious schools, however, a multiple and progressive series of tasks was set, with each stage followed by tests and students constantly supervised to keep them from being distracted from their exercises. Such discipline, according to Foucault (1977), opens up an analytic space that coerces not only bodies but also minds: in learning to obey the new routines of elementary schools, Kodi children also learned to think in the new ways of the churches and offices.

Ideas of discipline and order become ingrained in mundane habits of everyday life; the attention that foreign missionaries dedicated to these more subtle aspects of "education" may constitute their most enduring legacy. While these ideas were cast as part of "development" rather than "evangelization" the two projects were intricately linked, and the first, though avowedly "apolitical" may in fact have had the greater impact on indigenous perceptions and practices. Studies of missionary activity in other parts of Indonesia (Kipp 1990; Bigalke 1984) have noted that in instilling the authoritative imprint of Western capitalist culture, missionaries have often introduced a new worldview but been unable to deliver the world to go with it. Converts, freshly inspired, were frustrated by their inability to maintain the standard they had been taught in school. The newly "rationalized" concepts of time and discipline they had learned could not be easily transferred to distant hamlets where they married and had children.

Recent Reinterpretations

Contact with foreign missionaries and an official, national vision of mono-theistic religion has altered both daily routines and intellectual habits on Sumba. In the 1980s, the period of my fieldwork, Kodi debates about what was included within "religion" and what was not included two camps. The first, defenders of the church, put together notes on Kodi language and beliefs, which preserve the coherence and complexity of their own village traditions while comparing them to the principles and events of the Bible. The similarities between Kodi custom and ritual and sacrificial practices described in the Gospels are highlighted. The apostates or exiles from the Christian community, by contrast, have taken a different tack: they record traditional beliefs and practices in the hopes of constructing a parallel system, one that rivals the Bible with alternative explanations of religious problems.

The best-known and most influential document of this antichurch group

is a buku agama marapu kodi , or "book on the Kodi religion" composed by my teacher Maru Daku and dictated to his schoolteacher son. The author had converted to Christianity in the 1930s after graduating from the first school to open in the region. In 1952, however, he seceded from the church during disputes about the proper burial of the dead. By the 1980s he was a well-known ritual speaker and an authority on traditional custom (Hoskins 1985). Toward the end of my stay he showed me the book he had compiled in response to our discussions of the relations of marapu beliefs and Christian dogma. Both its form and its style of argument were shaped by and in opposition to the teachings of the church, which he had learned as a young man. Its originality lay in insights into differences between the two systems and attempts to justify the marapu system in counterpoint to the Christian one.

The book begins with a list of the seven classes of spirits that are worshipped—moving from the Creator, on to the first man and woman, the house deity, the clan deity, the spirits of the house and garden, and finally the spirits of the dead. He then noted that "the marapu religion has things that are forbidden, just as every religion has its prohibitions." Given the Kodi fondness for the number seven, seven commandments were presented in traditional ritual language, which translated into biblical-like injunctions against stealing, killing, or deceiving one's kinsmen. Obligations to feed the deities and make offerings at certain points of the year were first negatively phrased (highlighting the dangers of presenting the invisible powers with impure food), then positively presented in an outline of each household's calendrical round of sacrifices. In this way moral discipline and temporal order were brought to the forefront, but again in a traditional context.

Sensitive to Christian criticism of the rhetoric of traditional offerings, Maru Daku went on to explain the humility and apparent deception that Kodinese conventionally used in addressing the spirits:

It is said that the marapu religion is a false one, because it is founded on lies contained in the prayers. . . . Even after a large harvest, one must still say that the bag of white rice where the cockatoos play is not full, and the sack of foreign rice where the parrots scamper does not burst at the brim. . . . Even if one has many buffalo and horses, dogs and pigs, one must still ask for more . . . so we always ask for more rice to eat and more water to drink. But this is not greed or deception: it is [done] because in our religion you cannot make yourself appear rich in front of the spirits, you cannot brag or show off in front of them. . . . The marapu religion teaches

you to make yourself seem poor to those above, to belittle yourself in their direction and make all that you do appear insignificant.

The contradiction he addresses here has to do only partly with modesty in pleading with the ancestors for fertility and prosperity. It also concerns the crucial difference between the Christian model of personal prayer, with its idiosyncratic expression of desires, and the formalized collective model of traditional prayer. What Dutch ministers interpreted as deception and lying was in fact integrated into traditional religious practice as an etiquette of respect and deference; these strategies defined appropriate attitudes toward the deities and stressed that worldly wealth can never rival the mythological opulence and abundance of the heavenly kingdom.

The book continues by elaborating other Kodi systems of order: a traditional numerology that equates the seven holes in the human body with seven classes of spirits and seven stages of ceremonial accomplishment in the feasting cycle. Social stratification was represented on the model of the human hand, moving from the thumb, which stood for the prominent leader, to the little finger, representing the slave. Rules regulating the performance of ceremonies to shift residence or to call back the souls of those who had died a bad death were included. Local practice was defended as simply "another path" that led in the same direction as that of the Christian church, but one that was known to its followers only through word of mouth (Hoskins 1987c, 156-57).

Finally, he finished with an extended history of the oldest Kodi villages and a genealogy that traced the inhabitants of certain lineage houses back seventeen generations. Obviously modeled on biblical genealogies, this evidence was marshaled to demonstrate the historical depth of Kodi tradition and the fact that links to the time of the ancestral mandate were still intact. "The Christians have their book, but we have our stone ship and our tree altars, whose heritage has been transmitted to us by the language passed down through the generations and the speech sewn up into couplets."

The very eloquence of this plea for understanding and tolerance for marapu practice is couched in the terms of universal principles introduced from the outside. As a catalogue of rules and ritual practices, the book is an accurate document that stresses sequences and regimentation. As a dialogue with Christian critics, it presents an apologia in a new vocabulary, an effort to abstract dogmas and principles from a mode of symbolic action whose logic was until then basically implicit. By dictating this text to his son, Maru Daku transformed traditional worship even as he interpreted

it, for he believed that only by assimilating marapu ritual to the categories of monotheistic religions could its true value be recognized and articulated.

Maru Daku died in 1982, but his work influenced a new generation of Kodi ministers who have also tried to rethink the relations of Kodi custom and Christian belief. In 1984, I attended and taped a synod of ministers and evangelical teachers in Bondo Kodi. Discussion was carried on by three Kodi ministers—Hendrik Mone, Martin Woleka, and Daud Ndara Nduka— who sought to establish a unified church policy on three topics that had been problematic in the past: ritual feasts, marriage, and burial customs. Significantly, the most frequent interpretive strategy was to find a parallelism between Christian theology and the implicit doctrines of local practice, so that an accommodation could be established.

The analysis of worship at traditional altars and feasts provides an illustration of this method of resolution. Pendita Daud, speaking first, noted that in the Old Testament when Jacob dreamed of meeting with God he took a large stone and set it upright as a sign that his land had been given to him by God. He promised God that if He continued to give him blessings and help him along the way, later he would build a house and hold a feast there, to thank the Lord for his blessings. Pendita Daud then explained:

This is the same sequence that we follow in Kodi feasts, when we start in the gardens, and promise the marapu that if they give us prosperity, later we will hold a bigger feast in the ancestral village. Then, if we are allowed to live to continue our efforts, we will drag a gravestone and consecrate it with another feast. In all of these prayers, we may mention the Creator, but we give the requests to our ancestors, since they must serve as messengers. In fact, the Creator is always connected to them, as if by a slender thread. But since the Creator is too far, the Kodi embraces first those who are closer to him—his ancestors. Local customs such as we have here do have a religious content, but it is still obscure. Since it was handed down by oral tradition, the names may have been confused.

It is common for local evangelists to invoke the authority of the Old Testament and its parallels with Kodi ritual practices. The peoples of ancient Israel, indeed, are presented as having had almost exactly the same customs as the Kodi ancestors, with practices like polygamy, interregional warfare, the taking of heads (although the Bible's most famous "headhunter" Judith, is confusingly female), and the levirate often being cited. The story of the ancestral migration from Sasar to Sumba and the division into different language groups is interpreted as a variant of the Tower of

Babel story, with present generations diverging from a more complete and unified order.

The New Testament was the text first carried into Kodi villages, and it is the only one so far translated into Sumbanese languages. Increasing literacy, however, has made the Old Testament more accessible; as a result, that book is often cited to furnish legitimating links to the ancestral past. Its reports of feasting, sacrifice, and political conflict appear familiar and understandable and are used to justify the continuation of local practices they resemble. "Our ancestors were like King Solomon and his companions, who did not know Jesus but prayed to the Supreme God under their own name for him." With this argument, the fulfillment of obligations to hold a promised feast or to rebuild an ancestral house can be defended even after conversion. Since it provides a Christian context for pagan practices, the Old Testament also reveals their value in maintaining the fabric of collective life and especially the integrity of exchange networks. "Even if we do not listen to the voices of the dead, we must respond to those of the living," some converts explained to account for their participation in feasts. Debts are reckoned not only to the ancestral spirits, but also to living companions who had given shares of meat at earlier feasts and deserved to be repaid.

Pendita Daud defended local custom in remarkably relativistic terms:

Custom [Ind. adat ] cannot be considered paganism [Ind. kapir ]. Culture [Ind. kebudayaan ] cannot be considered paganism. Neither custom nor culture is the enemy of the church. A better term than agama kapir is agama suku , the religion of a particular ethnic group. Marapu beliefs are the indigenous religion of the Kodi people, but we cannot say that they are all wrong. The gospel came into the world through the culture of Israel. In Sumba, the gospel has to be brought in through local culture, so that custom can help to communicate the gospel message.

What is most remarkable about this passage is the way it takes the "national" Indonesian concepts of "custom" and "culture" and uses them to bring traditional practices in through the back door, so to speak. If only "paganism" is the enemy of the church, and these traditional practices, rather than being really pagan, are in fact simply misapprehended versions of the gospel message, then it is possible for a person to be both a practicing marapu worshipper and a good Christian. That would seem to be the syncretistic message of his remarks, though still veiled in the rhetoric of a national vocabulary.

That same year, a woleko feast was held in Kaha Deta, Balaghar, at which these principles were put into practice. Sponsored in part by the family of the first Christian minister in the area, it was held in his ancestral village and featured prayers in ritual language and sacrifices. The ritual orators were asked to give a full history of the obligations and promises that formed the background to the feast, but to mention neither the seven layers of heaven and six layers of land that their words would travel past nor any specific upperworld deities. The Creator was named and praised, and the ancestors were acknowledged as honored predecessors, but no message-bearers were invoked.

The innovations of this feast were intensely debated. Some praised the revitalization of Kodi feasting in a "modern" mode; others condemned it as a woleka tana dawa , or "feast from a foreign land" which did not remain faithful to any traditional norms. One old priest said it was a bungkus tanpa nasi (Ind.), a "leaf bundle without the rice"—that is, although the top and bottom of a spiritual hierarchy were left, there was little filling in between. "If marapu are listening, they will refuse to hear this message" he said, "since it doesn't follow the stages [katadi ] that we know from custom."

Rationalized Paganism: Old Rites in New Times

Debates about the validity of these innovations continue, informed by an awareness of the different temporalities at stake. On the one hand, some people proclaim the entropic view that posits a gradual but irrevocable moving away from origins and ancestral completeness, with the recent wave of conversion just another aspect of this decline. For them, the past represents an ideal that cannot be realized in this world, an actuality lost to subsequent generations. On the other hand, there are those, like Pendita Daud, who employ a "historicist" view of tradition to argue for the continuing relevance of the past to the present. In the following passage, for instance, he interprets the meaning of sacred objects to a audience of Protestant religious teachers:

When Kodi people pray to stones or trees or sacred objects, they are praying to them as objects that contain a history, that are part of their past. They are used as reminders and intermediaries [Ind. penyalur lida ] to carry messages to the Creator, who is the ultimate audience of these prayers. The wudi pa hamulla, watu papendende

["tree planted, stone erected"] is simply a proof from the past which shows that they, too, called the Lord for assistance.

His remarks were controversial and provoked a response from his superior in rank, Pendita Woleka, that "Jesus Christ is the only intermediary needed by Christians. They do not need rocks or trees or ancestors." Many, however, were convinced that the church should accept that ancestral rites provide a form of indigenous education with regard to culture and history: "Christians can go to them because they should also learn from the past, but their prayers must be addressed only to the Creator."