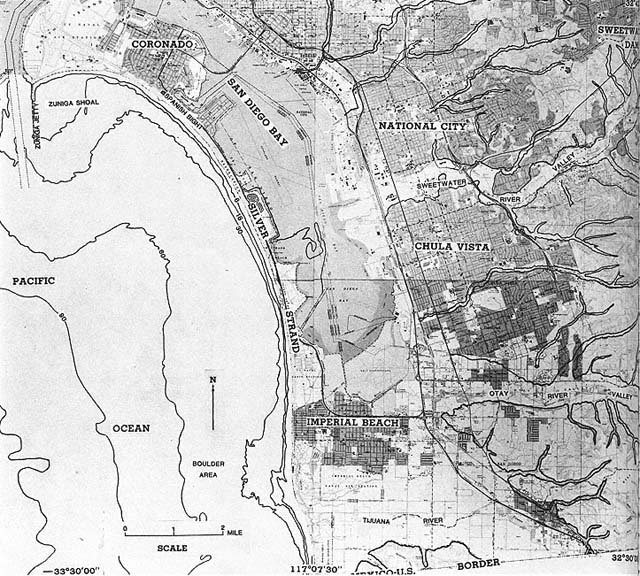

PART II—

DESCRIPTION OF COASTAL HISTORY IN GEOGRAPHIC SEQUENCE

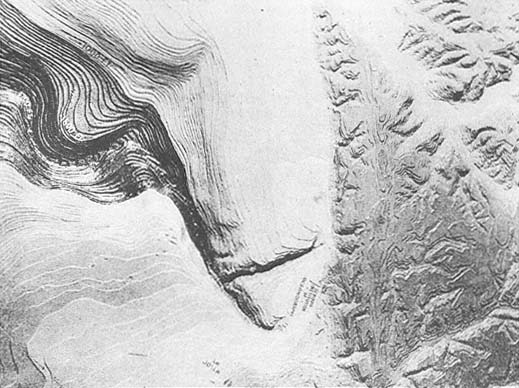

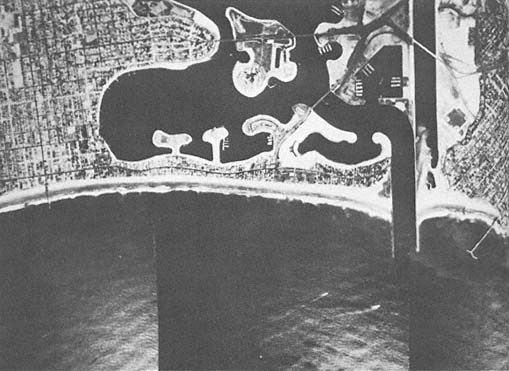

Figure 10

Littoral cells along the southern California coast and the southward termination of each

at submarine canyons.

From Inman and Frautschy 1966.

Figure 11

Oceanside littoral cell that extends from Dana Point to

the La Jolla canyons. The arrow indicates predominant

longshore current direction measured between 1950

and 1978. Since 1978, currents seem to have been more

variable. A recent investigation of Carlsbad Canyon

indicates that this canyon may be more important in

trapping sediment than generally had been assumed.

4—

San Onofre and Camp Pendleton Area

Oceanside Littoral Cell

Investigators have recognized a series of littoral cells along southern California (Emery 1960:27; Inman and Chamberlain 1960). These cells are based on general southerly drift of sediment, largely derived from rivers, and the entrapment of this sediment by submarine canyons which carry it out to sea (fig. 10) and by points of land that jut out perpendicular to the coast. The Oceanside Littoral Cell includes the area from Dana Point to La Jolla (fig. 11). This cell may be further subdivided at Carlsbad Submarine Canyon, although this generally was not recognized in the past.

The Faulted Coast at San Onofre and the Nuclear Power Plant

San Onofre State Park and Camp Pendleton are located in the north central portion of the Oceanside Littoral cell (fig. 12). A general idea of the character of the area is shown in figure 13, a photo taken when only the first building phase

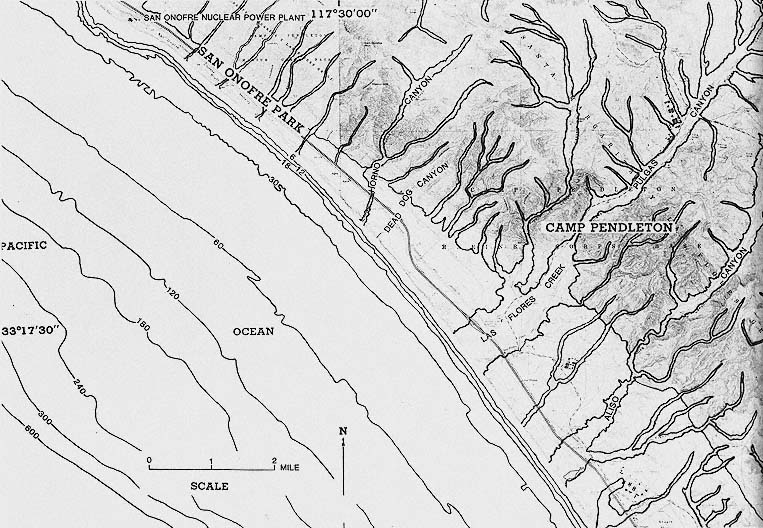

Figure 12

Location map of San Onofre State Park and Camp Pendleton.

NOTE: ocean bottom contours are in feet on this and other maps in the book.

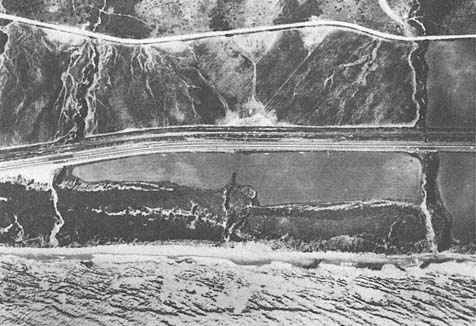

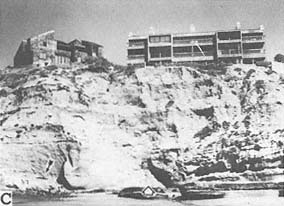

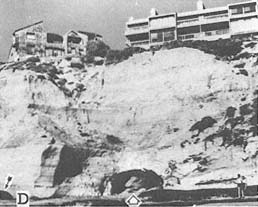

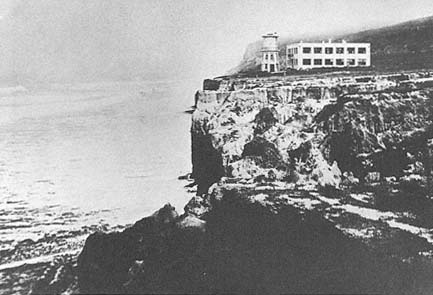

Figure 13

Oblique aerial view looking northwest at San Onofre Nuclear

Power Plant, located directly north of Camp Pendleton, 1970.

Since 1970, two additional units (nos. 2 and 3) have been built

at this nuclear power plant.

Photo : California Coastal Commission.

of the nuclear plant had been completed. The power plant is located on the coastal terrace, which is underlain by Miocene marine rock capped by Pleistocene marine and nonmarine sediments. These Pleistocene sediments are essentially horizontal and are easily eroded from the bluff face and along the canyons.

Approximately 80 percent of the cliffs between the power plant and Target Canyon six miles to the south, on Camp Pendleton, consist of landslides. The Cristianitos Fault is a major structural feature of the region and extends to within about five miles of the construction (not begun at the time of fig. 13) on the seaward side of the plant site. There is considerable difference of opinion among geologists as to the stability of the region relative to recent faulting (Converse, Davis and Assoc. 1970; Western Geophysical Co. of Amer. 1972; Fugro 1974; Hunt and Hawkins 1975; Ehlig 1977a , 1977b ; Fugro 1977; Woodward-Clyde Consultants 1978; Berggreen 1979; Greene et al. 1979; Legg and Kennedy 1979; Greene, Clarke, and Seekins 1980; Green and Kennedy 1981).

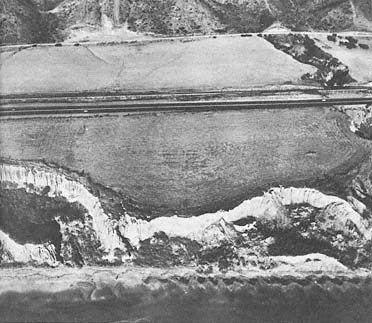

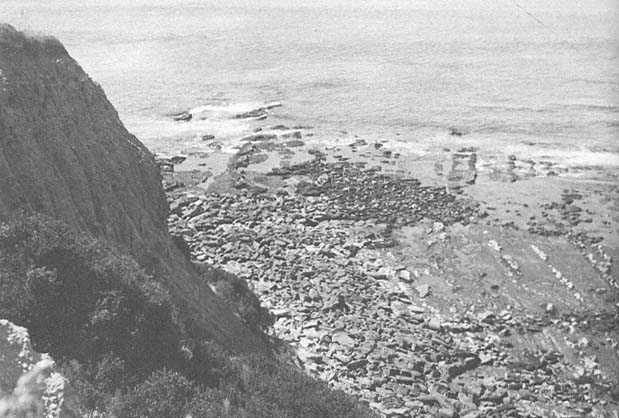

Figure 14

Vertical aerial view of the landslide of 1941 along the cliffs at Camp Pendleton, taken in 1953.

Photo : U. S. Dept. of Agriculture.

Nature of Coastal Cliffs and Canyon Erosion

Early studies of the area conducted by the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (1889a ) concluded that the bluffs eroded during each storm. They also noted that beaches from Los Angeles almost to San Diego were sufficiently wide and continuous to be traveled by horse-drawn vehicles.

The U. S. Army Corps of Engineers (Newton 1960) found that all triangulation monuments set out in 1934 were recoverable in 1958, suggesting that erosion during that period was slight. There were, however, only a few monuments, and they were apparently located outside the landslide zone. Thus a conclusion that there was minimal erosion is not well justified. Actually, there was one major landslide and considerable canyon cutting and bluff-face sloughing. Landslides appear to be directly related to intense sediment saturation and large storm swells. These conditions occurred only during the two wet

Figure 15a

Oblique aerial view along the bluff at San Onofre State Park, 1954.

Photo : U. S. Navy.

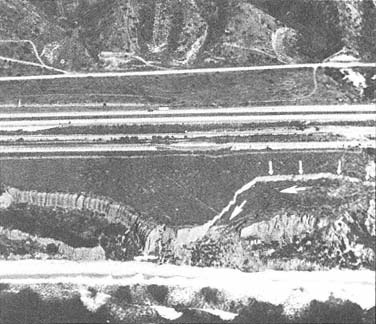

Figure 15b

February 1980 oblique aerial photo showing a landslide measuring 700

feet long by 300–320 feet wide, which occurred in the winter of 1978.

The small arrows show the direction of movement of landslide debris

toward the beach.

Photo : U. S. Navy.

years of 1941 and 1978 (Kuhn, Baker, and Campen 1980). The 1941 landslide measured 1,700 feet in length and 350 feet in width and was along a seaward-dipping plane (fig. 14).

More recently, in February 1978, a landslide measuring approximately 700 feet long by 320 feet wide occurred (figs. 15a and 15b ). The slide apparently was initiated by heavy rain which fell in January 1978. Since the slide, water has ponded on the head of the slump and produced a landward tilting of the bedrock, as shown by the only exposure at the lower end of the block, which dips into the slope. The scarp on the lateral margin on the upper part of the slide is

Figure 16

February 1980 view of the debris fan contributing sedimentary material directly to the beach.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

steep enough that slump blocks separate and move on the outer fringe of the main slide. Landslide debris continues to feed the beach as the toe is removed by wave action. Debris fans form in front of small gullies after every storm (fig. 16).

Accelerated Erosion Caused by Man

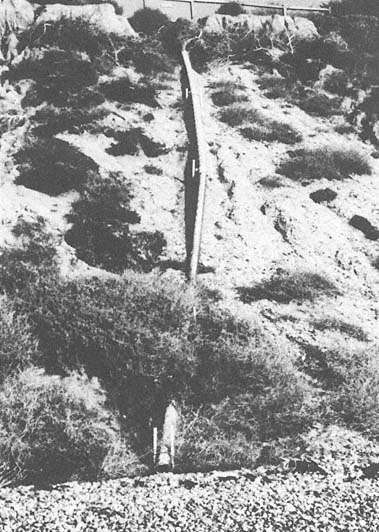

Since 1885 normal erosion along all drainage avenues has been drastically altered by man. Railroad trestles were built across canyons as early as 1885, but they did not alter the drainage patterns as far as we can tell. The construction of Highway 101, from 1912 to 1918, first altered the natural drainage patterns with the installation of culverts under the highway to channel surface runoff. In the wet years that followed, gully erosion accelerated where culverts concentrated water flow. In the early 1960s, still larger drains were installed under the new Interstate 5. These drains concentrated surface runoff from numerous drainage avenues, channeling it parallel to the highway and then west, under the highway and railroad tracks. There were no severe wet years following the completion of Interstate 5 until 1978, when rainfall was above average and was more concentrated than usual from January to April, and headward erosion along the altered drainage avenues greatly accelerated. The following are some of the

Figure 17a

Vertical photo of the canyon along the bluffs at San Onofre

State Park, 1969. The arrow points to the canyon head.

Photo : U. S. Navy.

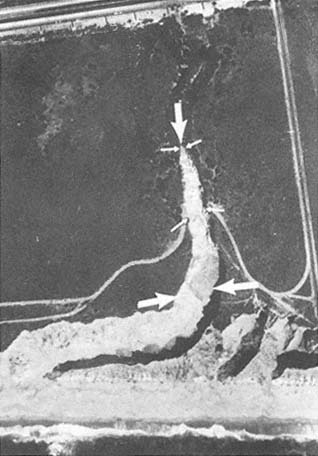

Figure 17b

March 1980 vertical aerial photo showing the development of

a 460-foot canyon perpendicular to the shoreline. It was

extended 235 feet on 20 February 1980 alone.

Photo : U. S. Navy.

more drastic results of this engineering practice.

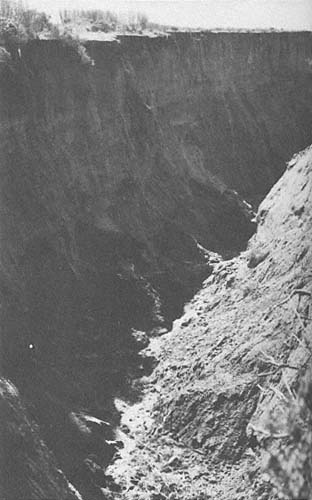

At Horno Canyon the southbound lanes of old 101 collapsed, leaving a seventy-five-foot deep scarp. At one location, no canyon with an axis perpendicular to the shoreline existed prior to the 1969 storms (fig. 17a ). Sometime between 1968 and 1976, a new canyon was cut perpendicular to the shoreline, about 60 feet headward. Then in January and February 1978 approximately 160 feet of headward erosion occurred, and on February 20, 1980 alone, the canyon eroded another 235 feet landward; this new canyon was 50 to 100 feet deep and 60 to 90 feet wide (figs. 17b and 17c ).

Figure 17c

February 1980 view of the canyon cut into the unconsolidated

colluvial bluff forming terrace deposits at San Onofre State

Park. The evening after the canyon was cut, a park ranger

nearly drove his jeep into the new canyon just before

dark, since it had not been there the previous night.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 18

January 1983 view looking down the newly formed canyon, showing how the

sand from the offshore bars has moved onshore to form a wide, new beach.

Dead Dog Canyon, south of Horno Canyon on Camp Pendleton, eroded approximately 560 feet headward between 1932 and 1977. During a two-week period in January and February 1978, this same canyon eroded another 100 feet, and approximately 100 feet more in February 1980. These are just two examples of man-induced erosion which have occurred during the wet years.

Bar System Formed by Rapid Canyon Cutting and Landslides

Prior to 1978 the beaches in this area varied in width from 40 to 60 feet, with few sandbars offshore. This changed in 1978, however, when stormy weather caused extensive erosion of the bluffs and canyons, which in turn provided sediment that widened the beach by at least 40 feet and caused sandbars to form offshore. There were more storms in 1980, and eight to ten bars parallel to the shore were observed afterward. This source of sediment had not been recognized previously, nor had it figured into the sedimentary budget of this part of the littoral cell. Since at least 1950, the predominant longshore transport direction had been from north to south. Had this continued to be the case, large quantities of sediment would have been deposited on the beach in Oceanside and to the south, but since 1980 the net longshore drift has been virtually balanced (Seymore 1980–1982). After the very stormy period from January through March 1983, the beaches along this fourteen-mile stretch of coast were markedly widened and presently vary from 60 to 100 feet wide. It appears that sediment derived from erosion of bluffs and canyons, and landslides between 1978 and 1982 moved back onshore in 1983 (fig. 18).

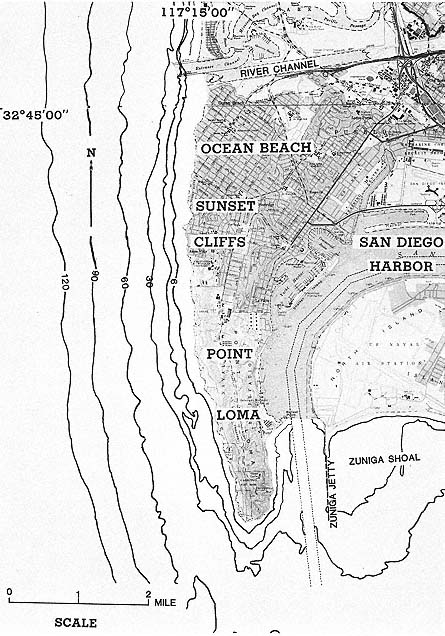

Figure 19

Location map of Santa Margarita River south through Oceanside and Carlsbad.

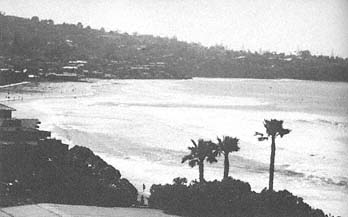

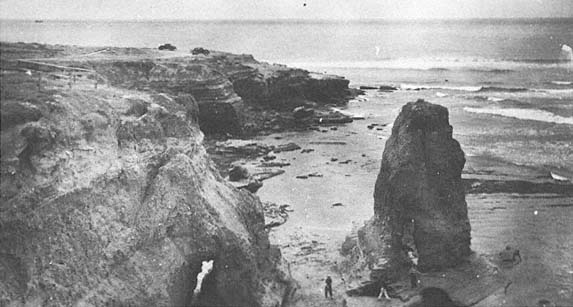

Figure 20

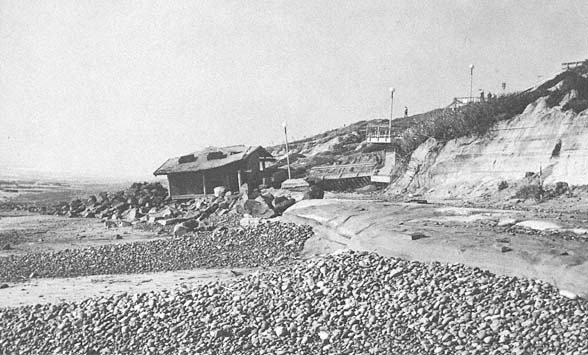

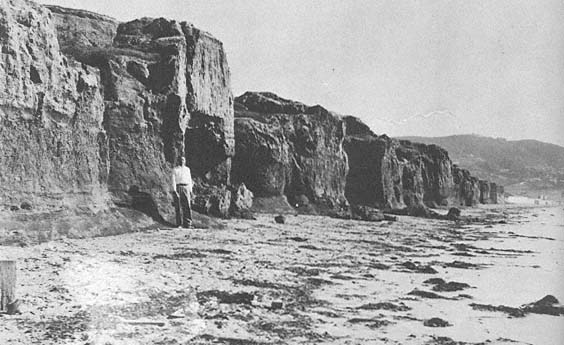

Summer 1885, photo looking north along the bluffs at Oceanside with the wide

beach below. Note the extensive landslide material fronting the cliffs, showing

a predominance of subaerial erosion and a lack of wave erosion.

Photo : SIO Archives, 4 July 1885.

5—

Santa Margarita River South through Oceanside and Carlsbad

Description of the Area

The terraces of the Camp Pendleton area terminate with the entrance of the San Luis Rey and Santa Margarita rivers which come to the coast just north of Oceanside. The City of Oceanside is built on the low terrace margin of Pleistocene nonmarine origin which extends on into Carlsbad and is about 30 feet above sea level (fig. 19). During the late 1880s the beach off Oceanside was approximately 300 feet wide (USCGS 1889b ). In former times this beach, which was practically unbroken from San Diego to Los Angeles, was used as part of a highway for horse-driven vehicles. The cliffs above the beach were retreating during the wet years of the 1880s as the result of subaerial erosion (fig. 20).

Works of Man

In 1888 a supply wharf extending approximately 1,080 feet into the water was built, and with it the first coastal construction began. This wharf, however, was destroyed by rough surf two years later. Nevertheless, local interests rebuilt the wharf, and it was altered and improved several times in the course of the next thirty years without detrimental effect to beach processes (Hales 1978). In 1927, a 1,132-foot open-pile recreational pier was constructed by the city of Oceanside at the foot of Third Street, just north of where the former wharf had been destroyed. The new pier has been severely damaged many times, during periods when depletion of the beach sand berm coincided with large storm swells and high tides. Some 200 feet of the pier collapsed in March 1978 during a perigean spring tide, and in 1983 another large section was destroyed.

In 1922 Lake Henshaw, the largest reservoir in San Diego County, was completed. The structure reduced the sediment-carrying capacity of the San Luis Rey River and thereby diminished the natural supply of beach material to Oceanside beaches. By 1925 the usable beach was quite narrow, and the beach width could be correlated with the stream runoff rate from the river (Hales 1978). The last storm-flood year to contribute appreciable amounts of sediment to southern California beaches was 1938 (Troxell et al. 1942). Following the floods the beaches were considerably widened, and the tourist trade flourished at Oceanside.

From 23 December 1940 through 7 January 1941, a series of storms originating in the Aleutian Islands moved into southern California and considerably damaged beachfront and bluff-top property (Kuhn and Shepard 1979a ). Houses in Oceanside were damaged or destroyed (fig. 21), and the beach berm was severely eroded elsewhere. A thirty-foot swell running along the coast coincided with gale-force winds and the perigean spring tide. Near Wisconsin Street in Oceanside, Sereno Court was damaged. The San Diego Union (27 December 1940) noted:

Figure 21

January 1941 beach erosion initiated by a severe storm.

Photo : D. L. Inman.

High tides and a pounding sea continued to damage the Oceanside shoreline. Combers broke over the end of the pier at high tide today. A crew of men worked all day yesterday and today to save El Sereno Court from being swept out to sea. Sandbags have been piled high against the buildings. The Arthur Neff home, which has been protected by a retaining wall, has received a severe buffeting from the sea. Foundations of the Guy Sensaba home are menaced. Precautions were taken today to hold back the sea.

Figure 22

Aerial view looking north across Oceanside toward the Camp Pendleton Boat Basin and the Oceanside Harbor, 1974. Note that

the width of the beach decreases south of the harbor.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Harbor Construction:

At Camp Pendleton and North of Oceanside

In 1942, under emergency wartime conditions, Camp Joseph Pendleton was created by the federal government with the purchase of Rancho Santa Margarita y Los Flores, immediately adjacent to the northern limits of Oceanside. In conjunction with the establishment of a Marine Corps camp, the federal government built a jetty and boat basin on the beach, just north of the city limits, in order to provide Camp Pendleton with a harbor facility and boat-turning basin.

The harbor began silting up immediately after the jetties were constructed, and much of the sediment which had been carried south to preserve the wide beaches of Oceanside was lost, necessitating continual dredging of the harbor and pumping the spoils to the south to replace the lost material (Inman 1976) (fig. 22). Despite clear evidence that jetties for the boat basin north of Oceanside would cause difficulties for the wide beach off Oceanside, pressure was applied, and in the early 1960s a small boat harbor was constructed south of the ill-fated turning basin at Camp Pendleton. In March 1960, Marine Advisors (1960) made a study for the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers relating to the size of storm waves that would be likely to hit the small-craft harbor site. They showed that waves of over twenty-five feet were recorded at Oceanside during the tropical storm of 23–25 September 1939. In spite of the danger of such storms, the harbor was authorized. In 1963, four million cubic yards of material were dredged to construct the Oceanside small-craft harbor and deposited on what were then the downcoast beaches. This dredge spoil material contained many cobbles, derived from floods of the San Luis Rey River (Hales 1978:20). Approximately ten million cubic yards of sediment, including cobbles, have been dredged from the Camp Pendleton Basin and Oceanside Harbor between 1942 and 1980 (Shaw 1980). Despite this large fill, erosion began almost immediately. In 1965, cobbles made their first appearance on the beach in front of Oceanside, as the beaches eroded.

Figure 23a

April 1981 view from the Palomar Airport Road looking south along the beach.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 23b

February 1983 view from the same vantage point as that in 23 a . Note the extensive cliff erosion.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Cobble Beaches

In southern California beach cobbles are derived from two sources: from rivers as the result of floods, and from sea cliff erosion (Emery 1955). The longest cobble beach in southern California is found in south Carlsbad (Emery 1960:184) (fig. 23a ). During the storms of January 1983, the beach cliff eroded six to ten feet in places (fig. 23b ). In 1960, Emery noted that the cobbles of this beach, which is presently owned by the State of California, were the result of local cliff erosion. Today, however, the cobbles are much larger and were most likely dredged from the Oceanside small-boat harbor to the north, as early as 1963.

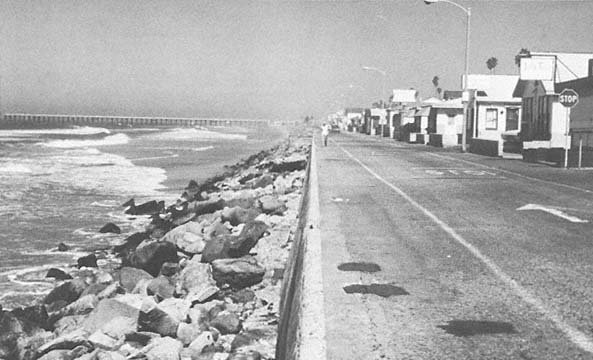

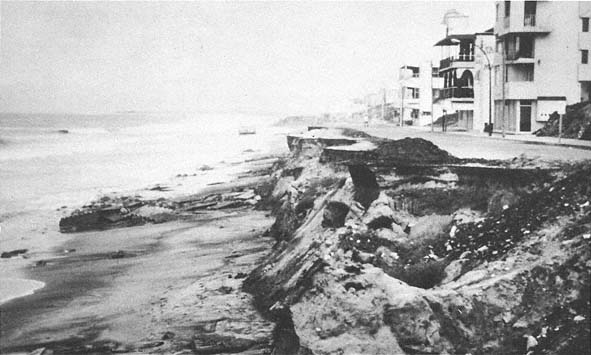

Figure 24a

September 1979 view looking north along The Strand at Oceanside. The structure and road were located on the

former beach. Riprap was placed to protect the concrete seawall and road.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 24b

February 1980 view looking at the same site as that in 24 a . The road and seawall were undermined and collapsed

between 12 and 15 February 1980; the waves were less than six feet high.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

During the storms of 1978 from the south, the beach sand was rapidly removed by storm surge, and the cobbles were withdrawn by the waves and thrown like artillery against houses at Oceanside (Kuhn and Shepard 1980). The cobbles became a destructive element again in the winter of 1980, contributing to the undermining and collapse of the beach road (figs. 24a , 24b ) and to the damage to apartments and homes along the shore (figs. 25a , 25b ). In south Oceanside, roofs collapsed and windows were broken as the cobbles again became projectiles (fig. 26), although the waves were consistently less than six feet in height. Even where riprap protected the shore, the cobbles moved as far as twenty feet up the beach (fig. 27a ). The stones were seen to move along the shore and by June 1978 had largely disappeared (fig. 27b ).

The Army Corps of Engineers (Hales 1978:27–32) suggested several alternatives for stabilizing the sand and creating a buffering beach at Oceanside. These included rock revetments, concrete seawalls, groin systems, sand-fills, breakwaters, and a permanent sand bypass system. At the present time sand-fills are the only method being attempted.

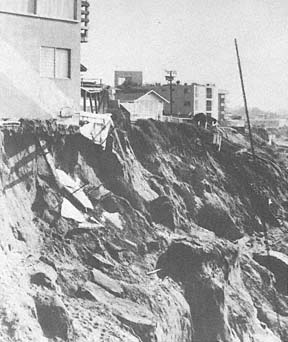

Figure 25a

View of beach cottages south of Wisconsin Street in Oceanside, 4 January 1978.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

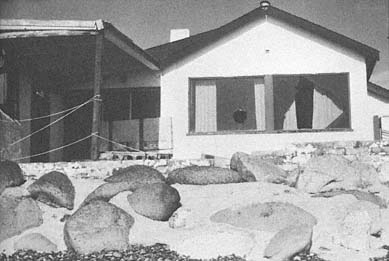

Figure 25b

View at the same site as that in 25 a , taken 17 February 1980. Wave and beach cobble

abrasion damaged houses along the shore during the February storms. Property damage

occurred as the result of cobbles being thrown by waves less than six feet in height.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 26

February 1980 view of the damaged beach cottage in south Oceanside.

Note that the windows were shattered and the roof collapsed as a result

of cobbles being thrown by relatively small waves.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 27a

January 1978 photo of beach cobble abrasion in south Oceanside. Cobbles

moved up the beach eighteen to twenty feet, covered the riprap seawall in

places, and eroded lawns behind the seawall.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 27b

June 1978 view at the same site as that in 27 a . Only remnant

pockets of cobbles remain.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 28a

April 1978 view of eroding beach at Carlsbad.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 28b

July 1980 view of the same site in Carlsbad. The sand did not return to the beach this year during the summer.

The cobbles have eroded behind and around the seawalls and the riprap and adjacent to the building.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Failure of Sand to Return to Beaches During Summer 1980

Beach processes monitored prior to 1978 indicated that sand levels drop during the winter (fig. 28a ) and return again approximately to their usual level in the summer. In the summer of 1980, however, the sand did not return to its usual level along the Oceanside-Carlsbad area (fig. 28b ). As noted previously the longshore currents changed after 1980 at Oceanside (Seymore 1980–1982). An additional factor may be that the Carlsbad Submarine Canyon to the south intercepted the sand offshore.

Figure 29a

December 1977 view of the storm drain designed to carry surface water

down and away from the slope face at Carlsbad State Park.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 29b

February 1979 view at the same site as that in 29 a , following the

collapse of the drain pipe, which caused severe erosion of

the bluff face.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Many cliffs in the area are actively retreating today, not in response to wave action, but primarily because of solution by groundwater and the fact that man has installed storm drains on the bluffs, which were designed to divert surface water away from the bluff face (fig. 29a ). However, in 1978, 1980, and again in 1983, many of these drains collapsed, and escaping water severely eroded the bluff face (fig. 29b ).

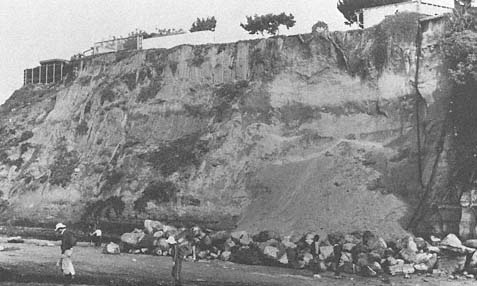

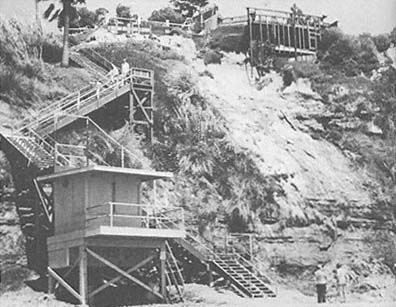

Figure 30a

January 1978 view looking north along Carlsbad beach.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 30b

February 1983 view at the same site as that in 30 a . The lifeguard tower is gone, the restroom and the stairway

have buckled and collapsed, and the cliff has retreated fifteen to twenty feet.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

If the formerly predominant southern transport of sand is not restored, it is difficult to estimate what will happen to the large quantities of sediment found off portions of the inner shelf south of the San Dieguito River (Fischer et al. 1981). At any rate, the beaches from Leucadia south to La Jolla grew during February 1982. An explanation is elusive at this point, but it may have something to do with the change of the longshore current direction. Erosion of the beaches and cliff retreat accelerated during the stormy months in early 1983. At Carlsbad Beach, where concrete restroom facilities and lifeguard towers were built directly on the beach prior to the 1978 storms (fig. 30a ), in 1983 two concrete restrooms were undermined and bombarded by cobbles and small riprap, and eventually collapsed and subsequently were removed. The adjacent cliff retreated by as much as fifteen to twenty feet during one storm (fig. 30b ). The coast highway near the Carlsbad Encino Power Plant was severely damaged and collapsed in places during this storm. Most of this very rapid erosion occurred during the storms of late January and early February 1983, which coincided with the perigean spring tide, a ten- to twelve-foot swell coupled with extremely strong winds.

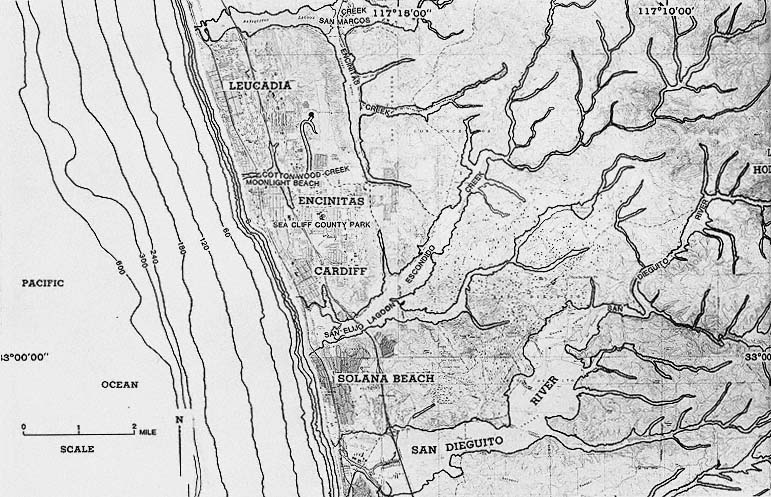

Figure 31

Location map of Leucadia, Encinitas, Cardiff-by-the-Sea, and Solana Beach.

6—

Leucadia South through Solana Beach

Description of the Area

The communities of Leucadia, Encinitas, and Solana Beach to the south are located on beach and dune ridges of Pleistocene marine and nonmarine origin, about 80 to 120 feet above sea level (fig. 31). Cliffs on the seaward side consist of ancient lagoonal-barrier sand bars and open coast sediments. Rapid erosion has occurred in recent years as a result of extensive grading of the iron-oxide cemented dunes and soil horizon along the bluff top. In several areas, the dune has been entirely removed by grading. As a consequence, the natural drainage patterns were altered, and where water had previously flowed landward, away from the bluff edge, it was allowed to flow over and down the bluff face, causing erosion during even the early stages of construction. Once a dune has been removed, the underlying uncemented sand is eroded rapidly.

Old Surveys and Maps of Encinitas Showing Extensive Coastal Changes

The California Southern Railroad surveyed the coastal route from Colton south to San Diego many times between 1880 and 1891, and it was during this time that the county surveyor, L. L. Lockling, surveyed the first coastal town between the city of San Diego and San Juan Capistrano. This town was called Encinitas (Little Green Oaks). John Pitcher had purchased the land of 244 acres at one dollar per acre. The surveys, dating from 1880 to 1883, show more land than exists today: especially large changes took place before 1892.

Five very wet and stormy years followed the surveys, and the county tax assessor records show marked devaluation of seaward property, with a corresponding short-term increase in property value for lots directly inside the bluff edge. By 1889 the coast had changed dramatically as shown on a U. S. Coast Survey map and on composites of the maps from 1880 through 1891 (fig. 8b ).

Of particular interest is the effect of the highly localized storm of 12 October 1889, when 7.58 inches of rain fell at Encinitas in eight hours, while only .04 inch fell at Los Angeles and .44 inch at San Diego during the same period. A water storage reservoir up-canyon from the present-day Moonlight Beach on Cottonwood Creek collapsed, and a great wall of water roared down the canyon, washing away the railroad bridge and destroying ranches in its path (U. S. Signal Service 1889:279). Subsequent county assessor records indicate a devaluation of downstream property and a short-term increase of property directly inland.

As previously noted, in 1884, following the eruption of the Krakatoa Volcano in Indonesia, a short-term climate change occurred in southern California. The weather changed from semiarid and very dry to subtropical, and world-record rainfall levels were recorded. During February 1884, storms lashed the coast, causing flooding of all rivers, and all but two of the railroad

trestles between San Bernardino and San Diego were destroyed. For obvious reasons there was no building being done on the bluffs, beaches, or flood plains, or in the canyons during this period.

Construction on Bluff Tops and Methods for Preventing Bluff Erosion

Beginning in about 1973 condominiums and apartments have been constructed along the bluff tops, many within ten feet of the edge. Numerous recent geologic studies done by consultants for real estate developers indicate negligible erosion of these bluffs since 1928, based on early aerial photographs. What was not readily apparent to the investigators is that bluff and cliff erosion is episodic, site-specific, and directly related to climate changes. The impact of urbanization on the cliffs was also not taken into account.

Examination of sequences of photographs of a specific site revealed not only that erosion occurs sand-grain by sand-grain but also that it is largely episodic in nature, often involving failure of 100 feet along the cliff at one time. In 1973 it became apparent that in the middle of a drought period, cliff collapse was caused at least as much by groundwater and the effects of man as it was by wave erosion.

The groundwater table began rising in 1973, commensurate with urbanization of the adjacent areas. This rise resulted largely from an excessive watering of lawns and the introduction of non-native vegetation to the region. Other contributing factors include agricultural irrigation, leach lines, and cesspools. Sorbon and Sherrod (1977) indicate that overirrigation of landscaping in residential subdivisions alone is equivalent to fifty to sixty inches of rain per year on each lawn. This extensive overwatering in coastal areas has at least three important effects: it has caused a slow but steady rise in the water table, even during the driest period preceding the rainy year of 1978; it adds

Figure 32a

Views of landslide along the bluffs in south Del Mar, 1977. Note that the groundwater

caused movement of the landslide directly seaward from the new construction during

this drought year.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 32b

February 1978 view of block fall and debris at H Street in Encinitas.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

weight to the cliff material and increases pore pressure; and this in turn contributes to landslides (fig. 32a ) and blockfalls (fig. 32b ).

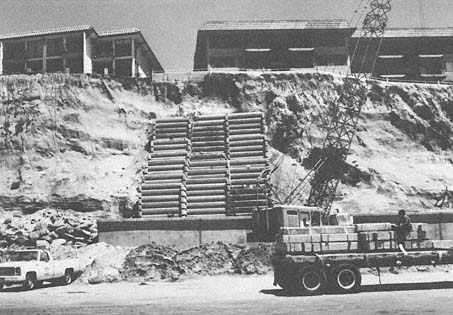

At one location condominiums were constructed over an unrecognized ancient river channel fill (figs. 33a , 33b ). Erosion at the base of the cliff, at the southern end of the condominium site, amounted to ten feet between 1971 and 1978 in two separate five-foot episodes. The homeowners in the project have gone to great expense to stabilize the cliff base and bluff face. In April 1978 a concrete crib wall, designed to prevent further erosion, was near completion (fig. 34a ). However, during the first week of May the crib wall collapsed, severely eroding the bluff face (fig. 34b ). A concrete seawall now exists at the cliff base, and the upper bluff face has been terraced with concrete (fig. 34c ) at a cost of over $2 million to the homeowners.

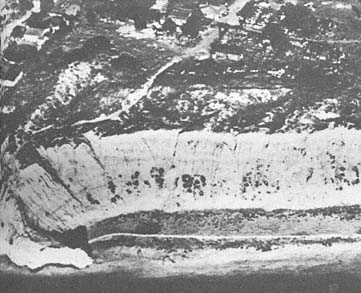

Figure 33a

Oblique aerial view of a portion of south Solana Beach prior to the

bluff-top development, 1954.

Photo: U. S. Navy.

Figure 33b

View of the same site as that in 33 a following development of the bluff

top, 1974. Note that the bluff face began eroding during the construction.

Photo: B and A Engineering.

Figure 34a

April 1979 view of the concrete crib wall being installed on the bluff face at Solana Beach.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 34b

May 1979 view of the same site as that in 34 a . Note that the crib wall collapsed

before completion.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 34c

View of the same site, 1980. The bluff face has been terraced with concrete, and the adjacent bluff face south of the terraces

has been planted.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 35a

View of a cave forming above sea level along a remnant of shear zone

in Leucadia, 1980. The cave was formed primarily as result of inland

groundwater exiting the cliff face.

Photo: G. Kuhn, January 1980.

Figure 35b

View in the vicinity of 35a , showing the extensive cliff erosion that occurred during the storms of

January through February 1983.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

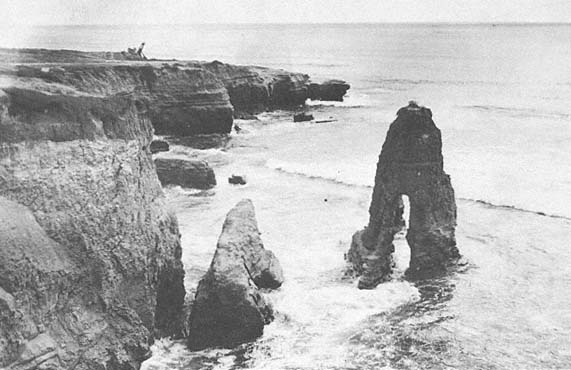

Formation and Collapse of Caves and Arches

A unique feature of this section of coast is its caves and seldom-formed arches. The caves are of three different types. First, in Leucadia, the caves are formed along weak rock shear zones four to eight feet above sea level and are solution-formed in origin rather than entirely caused by wave erosion (fig. 35a ). These caves enlarge laterally into the cliffs. They may grow downward and enlarge rapidly as they are abraded by beach cobbles and waves. Accelerated cave and cliff erosion occurred during the stormy period of January to March 1983 (fig. 35b ). Many cave roofs collapsed and cliff retreat amounted to ten feet in places.

Figure 36a

Oblique vertical photo of condominium

construction in south Solana Beach, 1974.

Note the small cave at the base of the cliff.

Photo: B and A Engineering.

b . View of the same location as that in 36 a , 1975. The sea

cave was formed by beach cobble abrasion and marine

erosion along the vertical remnant shear zone and along

the essentially horizontal weak bedding plane. Note the

recent collapse of the upper unconsolidated sands.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

c . View of the same site as that in 36 a and 36b , 1977.

Note that the sea cave on the left has collapsed.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

d . June 1978 view at the same site as that of 36 a –c ,

following the storms of February through April

1978. The recently enlarged sea cave is the result of

beach cobble abrasion during high tides.

Photo: Sea Grant/G. Kuhn.

Figure 36e

April 1983 view at the same site as that at 36 a –d following the

latest collapse of the massive sea cave roof.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Second, exposed caves in Encinitas and Solana Beach are mainly marine in origin and are seen to enlarge and collapse as a result of beach cobble abrasion with relatively small wave activity (figs. 36a –36d ). During the storms in January to February 1983, a massive sea cave roof collapsed, endangering the buildings on the bluff above (fig. 36e ). Third, a recent geological investigation in Solana Beach (Libby 1978; Shepardson 1978) indicates the presence of a large subsurface cavern inland of the cliffs (fig. 37). Concrete was poured into the void that had been encountered during construction. When it was not filled after forty-five minutes, it was assumed that the concrete was flowing into an intricate passageway. Normally such caverns occur in limestone or other soluble rock, not in sandstone. Solana Beach also has sea caves and tunnels caused by wave, sand, and cobble erosion.

Figure 37

Map showing locations of the sea cave in the cliff face and the

cavern located directly inland. During construction, concrete was

poured into the cavern for forty-five minutes before it was realized

that an intricate passageway had been encountered. From Libby 1979.

Figure 38a

December 1982 photo showing the early stages of a rapidly

enlarging sea arch forming in weakly consolidated rock.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 38b

January 1983 photo showing the same site after the arch

collapsed.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

During the storms in January 1983, many of these caves and tunnels were enlarged in as little as two days. Surprisingly, an arch was seen to form in the slightly consolidated Del Mar formation of Eocene age. It enlarged rapidly between 27 and 30 December, 1982, and collapsed on 1 January 1983 (figs. 38a , 38b ). As far as we know, this arch was formed by the hydraulic effect of moderate and excessively high tides, and without any cobble or sand abrasion. In late January and early February 1983, six feet of cliff face directly adjacent to the arch site also collapsed (fig. 39).

Figure 39

View of the cliff collapse at north Solana Beach, 1983.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 40

April 1983 view of the public stairway to the beach. The stairs,

in north Leucadia, were crushed by a mass that separated from

the cliff.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 41

View of the private stairway that collapsed in Leucadia, 1978. Note that

the stairs failed as a result of a small storm-drain collapse.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 42

Photo of the stairway at D Street in Encinitas which collapsed as a result of surface

water flowing down the adjacent street end, undermining the underlying buried water

main and causing it to buckle, break, and erode the cliff, 1978.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Loss of Beach Access Stairs

Public and private stairs of various types of engineering design were located along this section of coast. In March 1983 a section of cliff collapsed, crushing a public stairway and injuring several people who were on it at the time (fig. 40). This apparently was the result of a combination of wave erosion at the cliff base and groundwater sources inland. Along this same section of Leucadia, almost every homeowner, at one time, has had a private stairway to the beach. Most of these stairways have collapsed in recent years, often because of their proximity to broken storm drains and pipes (fig. 41), and many have fallen victim to storm waves. The severe winter storms of 1983 crushed many stairways and caused as much as ten feet of cliff retreat.

In Encinitas the cliffs are much steeper than elsewhere, and not many stairways, either public or private, have been built. One public stairway was constructed in 1977 at D Street at a cost of $100,000. This collapsed during the February 1978 storms (fig. 42), and it cost over $80,000 to remove the debris and replant the slope. This collapse, which resulted from surface runoff eroding an underground water main, should have been anticipated, since waterfalls had been observed at the site during winter storms in the 1940s. At the time of this writing, the county of San Diego has proposed to reconstruct the stairway at the same site.

Figure 43

November 1977 photo of the apartment complex at F Street

in Encinitas. In the fall of a drought year 110 feet of cliff

collapsed as a result of subaerial erosion (groundwater

table rise) rather than marine erosion.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 44

View of the public stairway at the Sea Cliff County Park in Encinitas, 1978.

A similar stairway collapsed and was crushed by a cliff failure at this

location in 1963. Note the recent cliff failure to the right of the stairs.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 45

June 1977 view of the public concrete stairs at Solana Beach. The

stairway was located in the northern end of the embayment and was

thus semiprotected from direct wave action.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Directly south a private stairway collapsed and was crushed by a 110-foot section of cliff in November 1977 (fig. 43). Stairways in Encinitas are subject not only to erosion by wave action and surface runoff but also to erosion by groundwater, as was the case when the stairway at Sea Cliff County Park collapsed in 1963. There was no public beach access at this location until the following year. The supports for the stairway now in use are being undermined and are separating again as the result of groundwater erosion (fig. 44).

At Cardiff State Park to the south, access stairways are partially protected at the base of the cliff by large blocks of stone, but the cliff itself is eroding around the stairway as water flows over the bluff and down the wooden stairway supports. Of the three public stairways in Solana Beach, two were thought to be particularly well designed in that the base of the stairs was located in protected cove areas away from direct wave action (fig. 45). During storms in late January 1983, however, the base of one stairway was completely destroyed by large waves (fig. 46).

Figure 46

February 1983 view of San Diego County public beach access stairway at Tide Park in

Solana Beach. Note that the lower portion of the stairway was destroyed during

the storms of January 1983.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 47a

Oblique aerial view of the Self-Realization Fellowship temple at Encinitas, 1938.

Photo: Self-Realization Fellowship.

Figure 47b

View of the temple collapse in the early 1940s following significant sea storms

accompanied by intense sediment saturation of the bluff top.

Photo: Self-Realization Fellowship.

Erosion History at the Self-Realization Fellowship Property

In 1938 the Self-Realization Fellowship built a temple on the bluffs at Encinitas (fig. 47a ). Following storms in 1941 the temple, which had been constructed thirty feet back from the bluff edge, was a victim of frontal landslides and collapsed to the beach (fig. 47b ). This property is especially prone to erosion, and numerous landslides have occurred as a result of wave action as well as from a rise in the groundwater level. Piezometers, placed in wells on the site, clearly indicate a rise in the water table beginning in about 1973, commensurate with the inland urbanization (fig. 48). This rise began during the end of a drought period that lasted from 1946 to 1977.

Figure 48

Piezometric well readings from three locations on the Self-Realization

Fellowship property in Encinitas. The small arrows indicate landslide

or block-fall occurrence. There has been a slow but steady rise in the

water table that began in 1973. This corresponds to extensive

urbanization and a marked increase in water use inland from this site.

Figure 49a

February 1978 view of the cliff at the Self-Realization Fellowship. Note that the cliff face is not abnormally

undercut but that excessive wet conditions are visible.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

Figure 49b

May 1978 view of the same site as that in 49 a , following the cliff collapse of 26 April 1978.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

In April 1978, a cliff collapse measuring 110 feet along the bluff and 12 to 15 feet landward, with a maximum height of 40 feet, occurred at this same site (figs. 49a , 49b ). Saint and Turner (1980) investigated conditions at the site, including the 1978 event, and indicated that the cliffs in the area are subject to collapse because of a combination of factors. They state "large blocks, bounded by weakened joints, fractures, and bedding planes move out laterally following a build-up of pore pressure under the attack of wave action."

Figure 50

Subsurface groundwater movement along the old erosion surface. The arrows

indicate the approximate direction of the subsurface water.

From Saint and Turner, 1980.

Figure 51a

View of the bluff face at the Self-Realization Fellowship, 1981. Note that the bluff face

was illegally graded and, as could have been predicted, it collapsed.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

After the storms in 1980, subterranean drains were installed around this property to intercept inland groundwater. Saint and Turner (1980) ascertained from a geological investigation that underground water was flowing directly under the Self-Realization property (fig. 50). An extensive stone seawall was installed along the cliff face in 1980. The bluff top was graded the following year, and, as could have been predicted, the cliff collapsed (fig. 51a ). Subsequently, it was covered with plastic sheeting to slow erosion of the bluff face (fig. 51b ). Since then the bluff face has been seeded and appears to be at least temporarily stabilized. Fortunately the winter of 1982 was very mild, with only a few storms and relatively little rainfall, so that not much erosion occurred. During the severe storms of January to March 1983, this was one of the few sites along the coast that was not damaged.

Figure 51b

May 1982 view at the same site as that in 51 a . Note that sheet plastic has been placed on

bluff face to slow erosion.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 52

March 1983 view of the bluff face at Cardiff-by-the-Sea. The highway collapsed at this location in the late 1950s.

The slope was stabilized, subsurface drain pipes were installed to intercept groundwater, and the slope toe was

semiprotected by installation of riprap. Note that riprap was scattered by the high surf in various places during the

storms of January through March 1983.

Collapse of Highway 101 and Subsequent Stabilization

In April 1958, a landslide occurred along the cliffs between Sea Cliff County Park and Cardiff State Beach. A section of Highway 101 collapsed, and one lane was lost for a distance of about 300 feet. The cliffs in this area, prior to the failure, were nearly vertical and were eroding as the result of groundwater from inland sources. In 1960, subsurface drains were installed parallel to the existing railroad track, inland from the cliffs, and pipes were run down the cliffs to remove the groundwater. The base of the slide was removed, the slope face cut back and stabilized, and rocks were placed along the base to slow future erosion. Many of the large rocks were scattered during the winter storms of January through March 1983, effectively cutting off lifeguard service even at low tide (fig. 52).

Figure 53

April 1983 view looking north along the beach at Cardiff. Note that the restaurants were severely damaged during the storms

of January through February 1983, when beach cobbles and riprap rubble became artillery and were thrown by large

waves into buildings and onto the coast highway.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

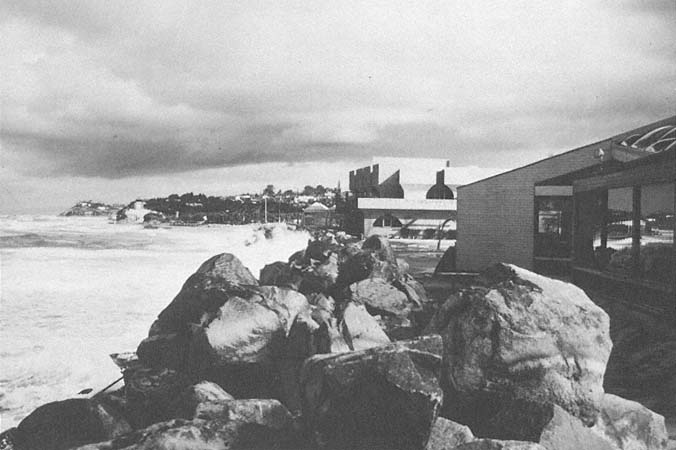

The Precarious Existence of Restaurant Row at Cardiff-by-the-Sea

During the past few years, numerous large restaurants have been constructed directly on the beach at Cardiff. This low-lying area has been inundated in the past when large storms breached or even temporarily removed the fragile sand barrier. During the last week in January and early February 1983, large storm swells, which coincided with the perigean spring tide, began to set the stage for extensive destruction along this area. Beach sand levels dropped markedly, and cobble rocks became projectiles, breaking out windows in the restaurants, undermining other places, and covering Highway 101 elsewhere to the south. The riprap rock that had been placed in front of one restaurant was ineffective in protecting the buildings and, in fact, many boulders weighing as much as 1,200 pounds were thrown through the air by the waves. This occurred where a large rampart of cobbles was formed in front of buildings; the large blocks of stone were first rolled seaward and then were catapulted through the structures. Some of these large rocks even came to rest in the middle of Highway 101 more than 80 feet inland. Since March 1983, larger riprap has been placed in front of the buildings and cemented (fig. 53). A great storm would probably break this barrier up leaving the restaurants in a definitely hazardous position.

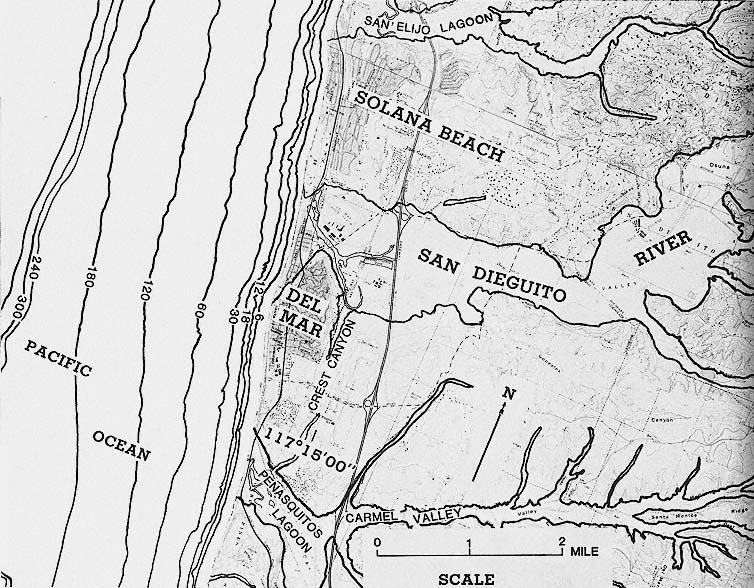

Figure 54

Location map of Del Mar and vicinity. Note: Bathymetry in feet

7—

Del Mar and Vicinity

Description of the Area

The city of Del Mar is situated partially on an inland coastal terrace and partially on a delta bordered by a low-lying beach to the north (fig. 54). It is adjacent to the flood plain of the San Dieguito River. The coastal terrace has a seaward margin with vertical to near-vertical cliffs consisting of weakly cemented, highly fractured ancient lagoonal barrier bar sediments of Eocene age. These sediments are capped by Pleistocene sand that is well cemented with iron oxide that tends to stand vertically even when undercut and appears to be more resistant to erosion than the underlying Eocene shale and sandstone. Inland and upland from the first coastal terrace, numerous canyons and gullies have been cut.

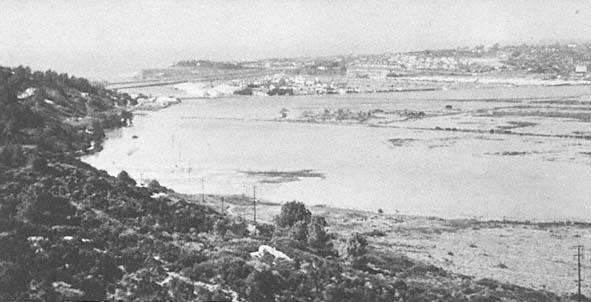

Figure 55

View of the low-lying Del Mar area which was flooded in February 1980. The view is looking across the San

Dieguito flood plain toward the Del Mar Racetrack which was partially underwater at the time.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

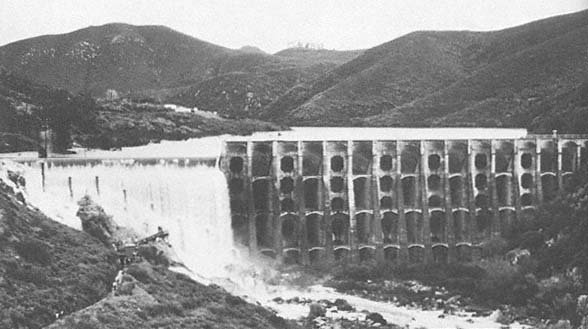

Figure 56

View of Hodges Dam on the San Dieguito River, inland of Del Mar, 1980. Note that this dam was designed for

agricultural purposes, not flood control, and has no flood control gate. The only means of releasing

water is a spillway. This dam could be breached by a major flood.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

San Dieguito River Flood Plain

The San Dieguito River is one of the largest rivers in San Diego County. Major floods occurred in past years, the most recent in March 1938. At present two water-storage dams, Lake Hodges and Lake Sutherland, are located on the river. Little usable beach sand or other sedimentary material reaches the coast today; instead it is deposited behind the dams. The State of California Department of Water Resources (1967) estimates that the sediment thickness of the flood plain varies from 100 to 150 feet.

When the water receded after the flood of 1938, a number of backers including Bing Crosby financed the building of the Del Mar Racetrack on the lower reaches of the flood plain. Exceptionally heavy rainfall occurred in February 1980, and once again the lower areas were flooded (fig. 55). Neither dam is equipped with flood control valves, and thus, when their reservoirs fill up, there is no way to let the water out gradually. It can escape only when the dams fill to overflowing (fig. 56), which may cause excessive scouring along the lateral margin, as during the flood of 1916 at Sweetwater Dam (fig. 9) (McGlashan and Ebert 1918). In recent years, business interests have exerted more and more pressure on the community to develop a large section of the flood plain. Should there be a recurrence of a major flood such as the one in 1938, and should the dams be full, it could be disastrous not only for the agricultural interests and the golf course, now located on the flood plain, but also for the racetrack and the major highways that cross the plain.

Figure 57

View of the glass-enclosed Natatorium on the beach at the foot of

Tenth Street in Del Mar, 1890s. This structure was designed to

protect the bathers from "the dreaded sting-a-ray."

Photo : Fletcher Collection, University of California, San Diego.

Figure 58

March 1978 view of the eroded beach at Del Mar. Note that the

wooden seawall collapsed and that adjacent lots were eroded.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 59

February 1980 oblique aerial view of the low-lying parts of Del Mar and the beach, which were

eroded both by waves and the flooded river.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

The Beach and Its Sand Replenishment

As mentioned previously, most beach sand in the area is deposited during river floods. Early settlers did not build homes on the beach, although they did construct some recreational facilities, such as the glass-enclosed wading pool at the foot of Tenth Street (fig. 57), along with other bathing facilities. By contrast, during the past quarter-century there has been extensive building on the sand beach. Many people, including some scientists, have overlooked the somewhat obscure evidence of past storms when the beach was deeply scoured.

Storms in 1978 and 1980 severely eroded the beach and undercut wooden seawalls, lifeguard towers, and even fences, patios, and homes (fig. 58). In February 1980, river flooding, combined with large storm swells, made the beach almost uninhabitable (fig. 59). Homeowners in the area periodically have sand transported in to rebuild the beach at their own expense. At one location an unusual method of beach stabilization was employed. A sand-filled tube approximately six feet in diameter was placed on the beach. Between 1980 and 1982 the sand levels had been high and the tube was usually covered. During storms in late January 1983, however, the tube was undermined and then collapsed, and was later struck by a bulldozer that was placing riprap rock revetment along the beach. The sand at this location had built up during February and March of 1982 as the result of the predominant south-to-north sand transport mentioned previously. However, sand levels again dropped in the winter of 1983, causing immediate panic along the shore as property was once again threatened. After seeing the damage done in 1978, 1980, and again in 1983, one questions what would happen to the homes along the shore during a really major storm, with waves larger than the maximum ten-foot heights recorded at fairly recent dates.

Figure 60

Oblique aerial view of Crest Canyon adjacent to the San Dieguito River, 1978. Storm

drains located up-canyon concentrated surface runoff and exhumed an old, filled

canyon which caused a massive alluvial fan to form in a portion of the filled

San Dieguito Lagoon.

Photo: G. Kuhn.

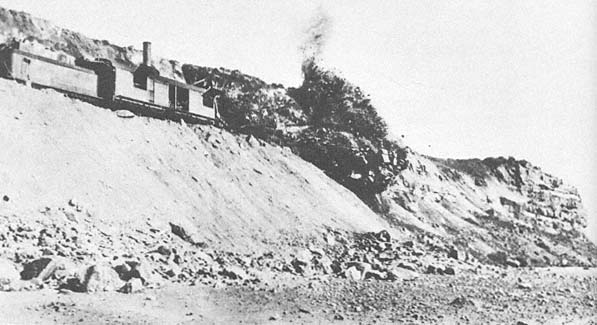

Figure 61

February 1910 view looking north along the bluff top at Del Mar, showing construction of the railroad bed.

Photo : Santa Fe Railway Company.

Coastal Canyon Erosion and Lagoon Siltation

The canyons surrounding the uplands of Del Mar have, for the most part, been formed by erosion during storms. Presently they appear to be inactive, as they are filled with alluvium. Erosion and down-canyon cutting of alluvial sediments occurred at Crest Canyon behind Del Mar in February 1978 (fig. 60). Storm drains that had been located on the upper slope of the canyon concentrated the water flow down-canyon from a housing subdivision, causing extensive erosion which exhumed an old canyon. As a result a massive alluvial fan, approximately 50,000 cubic yards, was deposited in the San Dieguito Lagoon, which is now a wildlife preserve (PRC Toups Corp. 1979). The lower part of the eroded canyon was artificially filled during 1979, but it eroded again in 1980. The same action was repeated in 1983. This is but one canyon on the coast where renewed erosion is a direct result of subdivision storm drains placed up-canyon.

Threat to the Railroad Along the Cliff and General Changes

Prior to 1900, the Santa Fe Railroad line was placed a block inland from the bluff. In 1910, the railroad relocated the route seaward because the grade inland was too steep and because the rail company wanted to accommodate the growing city of Del Mar (Atcheson, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway Co. 1978). To create a more level right-of-way, the bluffs were steam-shoveled and dynamited (fig. 61). Since then three trains have crashed to the beach, as the cliffs have been undercut by waves and by runoff from streets ending at the bluff, as well as by increasing subsurface groundwater pressures. The most recent train derailment occurred on 1 January 1941 when the bluff collapsed. This specific location in Del Mar is particularly susceptible to erosion, as surface water,

Figure 62a

August 1979 view of the cliff collapse at Del Mar. Note that this

failure was a direct result of subaerial erosion (groundwater sources

inland of the sea cliff) and not wave erosion.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 62b

September 1979 view along the bluff top at Del Mar. Note that the

block in the foreground has partially separated from the cliff face.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

especially during the wet years, flows directly down the street end, ponds east of the tracks, and then exits the cliff face atop impermeable clay layers. In 1978, during the January storms, this site collapsed, and the bluff face had to be stabilized again landward; subsequently the tracks were relocated still farther inland.

Recent Summer Cliff Failures

The vertical cliffs in the Del Mar area began collapsing in 1979, even during the summer, on account of increased groundwater flow (fig. 62a ). Tensional fractures occur along the top, parallel to the cliff face, and future failures appear imminent (fig. 62b ). Since 1980, very little sand is found on the beaches along this section of the coast, even during summer months, so that large waves at any period actively erode the cliff base.

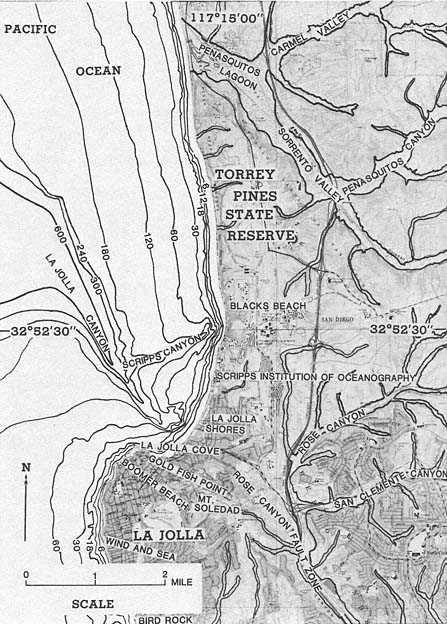

Figure 63

Location map of the Sorrento Valley south through Torrey Pines State Park,

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla Shores and north La Jolla.

8—

The High Cliffed Area between Sorrento Valley and North La Jolla

Description of the Area

The spectacular cliffs along this section of the coast reach a maximum height of over 350 feet and extend from Sorrento Valley (Penasquitos Lagoon) to La Jolla Shores. These cliffs consist of ancient lagoonal marine and terrestrial sediments of Eocene age, with a capping of iron oxide—cemented terrace deposits of Pleistocene age (fig. 63). At the south end, a volcanic dike of Miocene age cuts the sediments, and south of the dike there is an infilled embayment of late Pleistocene sediment, including iron oxide—cemented alluvial sands and gravels.

Figure 64

April 1983 view looking north along the undermined, collapsed portion of Highway 101, at the mouth of the Sorrento

Valley.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

History of the Lower Reaches of Sorrento Valley

Among the earliest inhabitants of the area were the San Diegueño Indians. Numerous shell midden deposits have been found along the high slope surrounding the valley. Shells have been dated by amino acid method to about 4,500 to 10,000 years old (Masters and Bada 1978).

The northwesterly trend of the valley is thought to be structurally controlled as it parallels the La Nacion Fault to the south, and as it is oriented in an anomalous direction toward the lagoons to the north. In 1874, Judge Benjamin Hayes described the extensive cobble barrier that completely sealed off the mouth of the lagoon and noted that its height exceeded forty feet above sea level. In 1889, the California Southern Railroad installed a beach shingle railroad siding in order to mine cobbles for use as abrasives and as paving material for the streets in the city of San Diego. The highway at this location was severely damaged between January and April of 1983 as storm waves launched beach cobbles and riprap against and onto the road (fig. 64).

In 1883 the railroad company located its right-of-way through the valley. During the great storms and flood of 1884, the railroad had to be dug out after massive landslides sealed off the lower valley and buried the track (San Diego Union , 2 March 1884). Since then, Sorrento Valley has been flooded on several occasions, the last time in 1938. At that time, only ranches and farms existed there, and the structures were high up the slopes, safe from the floodwaters. In the late 1960s, however, extensive development took place in the eastern section of the valley, and it is now a huge industrial park. Future floods could be rather serious, since there is no adequate flood control channel to handle a large volume of water.

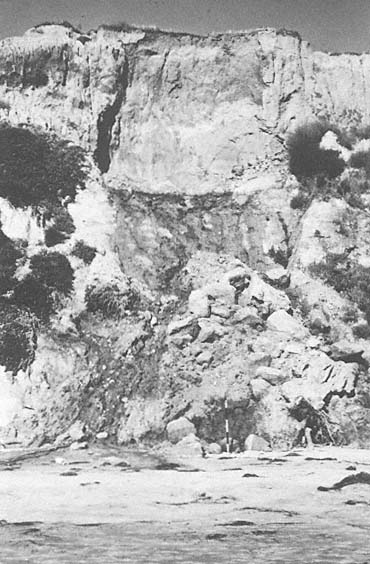

Figure 65

Oblique aerial view of the cliffs looking south at Torrey Pines State Park, south of Del Mar.

Bathtub Rock is visible at the far right.

Photo : California Coastal Commission.

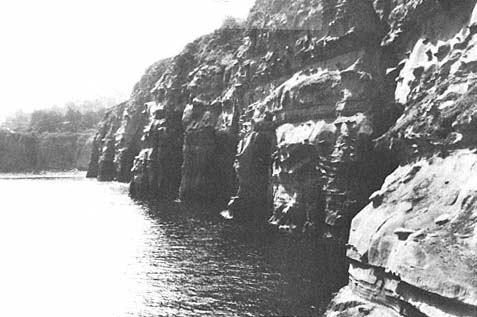

Figure 66

View of Torrey Pines landslide which measures approximately 1,700 feet along the

cliff, 1949.

Photo : F. Shepard.

Torrey Pines State Preserve and Its Cliffs

Thanks to the generosity of Miss Ellen Scripps, Torrey Pines was purchased as a state preserve in the 1920s. These magnificent cliffs and canyons thus have been preserved in their natural state and may be enjoyed by the general public. Cliff retreat along this area occurs in small rockfalls, as far north as Bathtub Rock (fig. 65). Bathtub Rock itself was hollowed out by a Welsh coal miner who thought it looked promising for a coal seam, but nothing of the sort was found. Just north of Bathtub Rock, a path leads up to the Torrey Pines State Park Center. To the left of the trail, as it leaves the cliffs, is a small sand deposit with many beach-type shells at an elevation of sixty-five to seventy feet above the present sea level. These sediments show the typical beach laminae. The shells have been dated at approximately 120,000 years B.P ., both by uranium thorium and amino acid dating methods (Masters and Bada 1978). This is an uplifted remnant of the beach from a period of relatively high sea level during the latest interglacial stage.

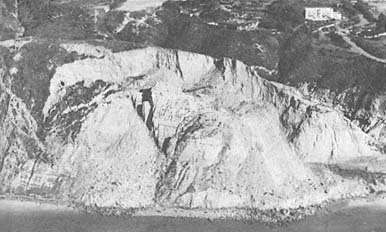

Torrey Pines Landslides

South of Torrey Pines the cliffs are disturbed by extensive landslides. The largest of these measures approximately 1,700 feet along the cliff and several hundred feet landward and is called the Torrey Pines Park landslide (fig. 66). When the U. S. Coast Survey mapped the area in 1889, this landslide and others to the south appeared to be quite recent, as talus and debris extended far out on the beach. The Torrey Pines Golf Course is located along the top of the bluff just south of this point, and in 1982 new fractures were noted directly inland from the old landslide.

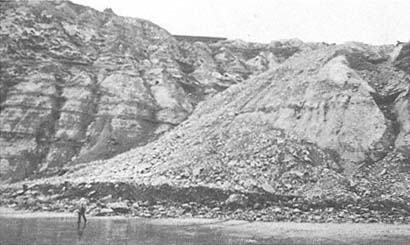

Blacks Beach Landslides

Blacks Beach (now Torrey Pines City Beach) has vertical and near-vertical cliffs over 350 feet high. During the summer, as many as 50,000 people may be on the beach at one time. For many years Blacks Beach was the only legal nude beach in southern California, and even today the practice is not entirely eliminated. It is fortunate, considering the large numbers of sunbathers, that few landslides have occurred in recent years. In the past, Blacks Beach has apparently experienced very large landslides, as noted by Sumner and Ross (1930). They described a failure between 1917 and 1922 with dimensions of 450 feet along the shore, 175 feet to the base of the cliff (75 or 100 feet wide higher up), and approximately 200 feet of the vertical cliff face. Prior to 1940, a large talus buildup allowed access to a hanging valley. During the storms at the end of 1940, this talus was completely removed (Kuhn and Shepard 1979a ) and was not reconstituted until about 1970.

In February 1982, a massive landslide occurred at this same location, measuring approximately 750 feet along the cliff by 280 feet into the cliff (fig. 67). This slide carried material, including large boulders, across the beach to the water, cutting off one side of the beach from the other except at low tide. The fallen material comprised acres of sandstone and provided a large future source of sand for the beach. Prior to this movement, groundwater was seen on the cliff face, and tensional fractures were noted along the top by San Diego city lifeguards. A local engineering geology firm, Leighton and Associates (1981), had completed a reconnaissance study of the area in May 1981 and had mapped an existing old landslide at the site. At the time of their report, fractures existed farther back from the landslide head scarp, indicating sections of future failures.

The 1982 landslide occurred during a very benign winter with little rainfall and few storms. Interestingly, on the evening prior to the cliff collapse, the seismograph at Scripps Institution of Oceanography registered a surface wave, with no earthquake being reported. It therefore appears that collapse of this

Figure 67

Landslide at Blacks Beach north of Scripps Institution of Oceanography

(SIO) which occurred January 29, 1982. Note the recent slide material on

the beach and the fresh vertical scarp behind the slide.

Photo : Ron McConnaughey.

Figure 68

February 1978 view of the fall of 1977 landslide debris along the cliffs in front

of the former Drell residence.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

slide was forthcoming, as the earth shock indicated that a major section had broken loose. In 1977, before the heavy rains of 1978, a landslide occurred directly in front of the former Drell residence in the La Jolla Farms area (fig. 68) (SCT Consultants 1979). This slide included approximately forty-five feet of the yard on the seaward side of the house, and debris from the slide reached far across the beach below.

Figure 69a

March 1978 oblique aerial view of the National Marine Fisheries Building. Note the funicular tram built at a

precarious position north of the building, and the rockfall directly in front of it. An old landslide was

discovered to be under the building after it was constructed.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Spectacular Location of the U. S. Fisheries and Wildlife Buildings, and the Cliff Margin of Scripps IGPP Building

When Andy Anderson purchased the property along the sea cliffs just north of the Scripps Institution grounds, he developed the property to have spectacular views from his home of the cliffs to the north and beautiful Point La Jolla to the south. He never gave a thought to the possibility that a large building might be constructed next to his property and thus completely block his view to the south, but that is exactly what happened. The National Marine Fisheries Building was constructed in the 1960s just above the cliffs, north of Scripps Institution (fig. 69a ). The structures were exempted from local building code requirements for a preconstruction engineering geology study because it was a U. S. Government complex (Moore 1973). In 1963, geologists from Scripps Institution noted

Figure 69b

Sketch of the same site as that in

69a , showing the mapped and

the inferred structural relations

at the National Marine Fisheries

Building landslide, 1973. From

Moore 1973.

the possibility that the buildings were on a landslide (Frautschy 1963). A thorough study, conducted after the architects received a letter from the concerned geologists, ascertained that the Fisheries buildings did indeed stand on a block-glide landslide (Moore 1963). Periodic micrometer measurements were made between each of the four buildings of the complex, from September 1967 to April 1973. It was noted that during that period Building B moved down, relative to Building D, at a rate of 2.2 millimeters per year (Moore 1973) (fig. 69b ). However, it was noted by Moore (1968) that much of the measured movement was related to rather distant earthquakes. Previous investigators of the area (Hanna 1926:233; Vaughan 1932) noted the gross instability of these cliffs during wet years and the concomitant hazard of situating not only buildings but even access roads along the fragile margins.

There did not appear to be a good site for another building to the south of the Fisheries Building, since there was a ridge along the seaward side and a longitudinal valley on the landward side. However, on the suggestion of Dr. Walter Munk, who wanted a building in this location, and with the help of his architect wife, the University filled in the valley and constructed the building for the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP). In recent years, the west end of the building has developed a lean toward the ocean.

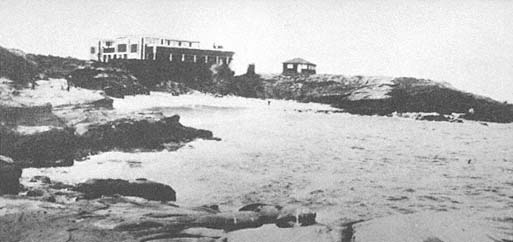

Figure 70

View of the low cliffs bordered by the wave-cut terrace at La Jolla, 1948.

Photo : F. Shepard.

9—

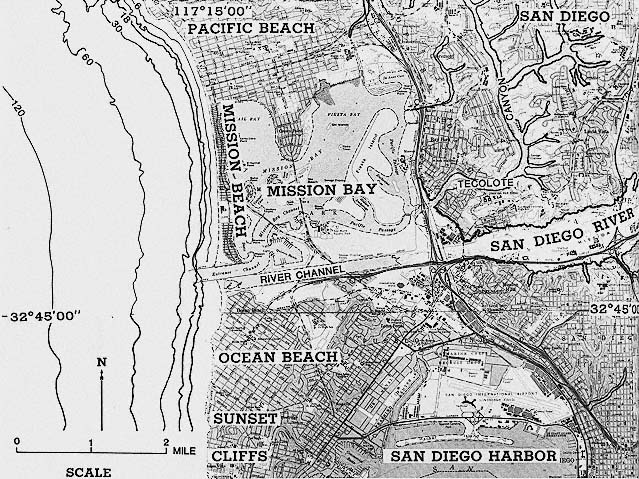

La Jolla and Its Projecting Point

Description of the Area

The La Jolla coast, with its northern boundary at the original Scripps Institution campus (now expanded considerably to the north), extends along the alluvial cliffs, now almost entirely guarded by seawalls, to the old barrier beach which historically enclosed a lagoon at the mouth of Hidden Valley (fig. 63). The lagoon now consists of only an artificial pond at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club, but it is low enough that it occasionally floods during heavy rains, temporarily submerging what is now a completely built-over area on the marshy soil.

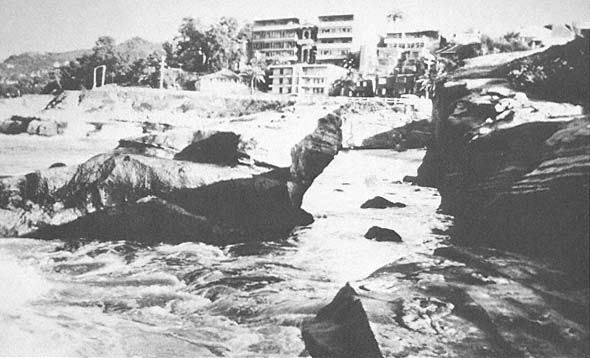

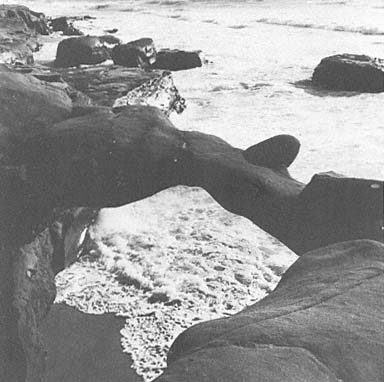

To the south, rocky cliffs with terraces rise above this low area and are bordered by a wave-cut terrace which is exposed at low tide (fig. 70). There is a right-angle bend in the coast where these terraces terminate. Point La Jolla extends seaward with an escarpment face that is based with deep reentry caves extending far back under the forty-foot high terrace which terminates at La Jolla

Figure 71a

View looking east at Goldfish Point, LaJolla, 1916. Note the unique development of the

caves for this part of the coast. They have presumably formed through a combination

of marine and solution erosion along pre-existing fractures.

Photo : SIO Archives.

Figure 71b

View of the same site as that in 71 a , 1978. Note that very little change is evident.

Photo : F. Shepard.

Figure 72

Early 1950s view looking south across Pacific Beach, Mission Beach, Point Loma, and

into Mexico. Note the Mexican Coronados Islands offshore in the upper right of

the photo.

Photo : F. Shepard.

Cove (figs. 71a , 71b ), one of the few protected swimming areas along the coast. Farther south, the point recedes but continues to be rocky with relatively low terraces and is indented by a few coves with steep, sandy beaches which derive their coarse sand from the local cliffs (fig. 72).

Figure 73

View of the original Scripps Building and water tower, SIO, 1910. Note the

absence of a talus at the base of the cliffs, indicating active wave erosion.

Photo : SIO Archives.

Figure 74a

View of low-lying alluvial cliffs south of Scripps, 1936. Cliffs were retreating at that time at a rate of about

one foot per year.

Photo : U. S. Grant IV.

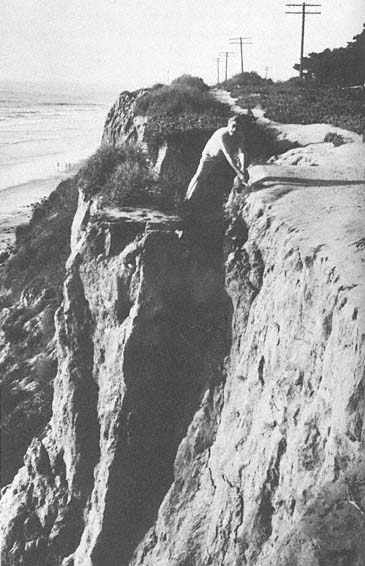

Alluvial Cliffs Near Scripps Institution

We have considerable knowledge of the history of the alluvial cliffs at the northern end of the La Jolla section of coast. The first buildings of the Scripps Institution were located just a few feet inside this terrace (fig. 73). Apparently the builders did not realize that this area was subject to rapid retreat, on the order of a foot or more per year, as was established by repeated measurements (Vaughan 1932). This was actually known earlier than Vaughan's work because seawalls had already been constructed in front of the Scripps buildings (Hanna 1926:233); nonetheless, retreat continued north and south of the wall until about 1946.

The erosion was found to be related to the fact that the sand beach was several hundred feet wide at low tide in the summer and was subject to depletion during winter storms (Shepard and Grant 1947). Generally the erosion began as a series of sand cusps, after which the waves completely removed the sand from the beach to expose underlying gravel and sometimes the underlying semiconsolidated alluvial formation (fig. 74a ). During late winter storms, this allowed the waves, with the help of cobbles, to undercut the alluvial cliffs and thereby produce the annual retreat. Beginning in 1946, however, the storms became less violent, and the beaches were not appreciably cut away in the winters, so the smaller waves that reached the cliffs were not capable of undermining them. Instead, over the next thirty years, most of the bluffs gradually became less steep, and vegetation became well established on the slopes. Only an occasional storm did any cutting, and then it was at the cliff base.

As a result, the builders, who rarely show interest in anything that may have happened more than a few years in the past, began building homes all along these apparently stable bluffs and filled canyons, some even extending support columns out over the inner beach. This practice was curtailed by the California Coastal Commission, however, in the 1970s.

In January 1978 the first severe storms in thirty years occurred and panic followed (Kuhn and Shepard 1979b ). Desperate measures of all sorts were tried in an effort to stop the erosion of the alluvial bluffs, which had been postponed for so long. In one threatened area, the homeowners obtained old cars and drove them onto the beach, hoping they would buffer the cliffs from the waves (fig. 74b ). The cars were soon smashed to pieces, posing little resistance to the high surf and leaving a pile of glass and steel frames on the beach. The steel frames were removed by the homeowners, and concrete was poured over riprap in another attempt to stop the waves (fig. 74c ), but the waves broke over the existing concrete wall, causing it to collapse (fig. 74d ) and greatly accelerating erosion of the adjacent property (fig. 74e ).

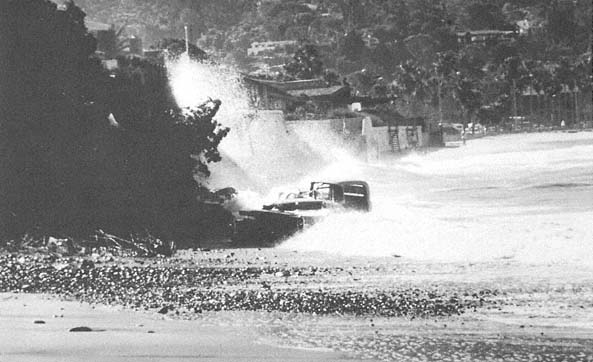

Figure 74b

January 1978 view at the same location as that in 74 a . A long, benign period with little erosion had just ended

with the severe storms of 1978. Note the remnants of old automobiles which were driven onto the beach

in an attempt to stop renewed erosion.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

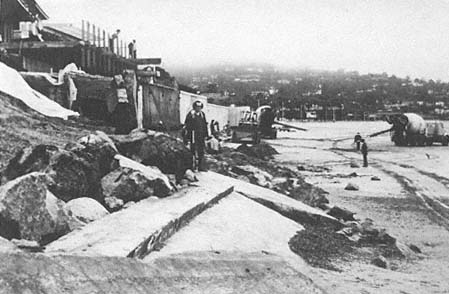

Figure 74c

February 1978 view at the same location. Automobiles have been removed from the beach, riprap was placed along

the slope toe, and the slope face was covered with gunnite.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 74d

February 1978, same location. Note the partial seawall collapse.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 74e

March 1978 view at the same location. 1978 storms produced local retreat of fifteen to eighteen

feet in this general area.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Elsewhere seawalls were begun. This method, however, was only partially successful, as some collapsed while being built. As this book is being written, most of the homes are protected by a substantial, continuous seawall (fig. 74f ), and only one small section at Scripps Institution remains unprotected. This last site is now being threatened, as evidenced by a number of cracks that became visible in the winter of 1982 in the pavement of the parking lot there. These cracks have since been filled. During the large storms of January to March 1983, however, the alluvial cliffs retreated about three feet as a result of cobble abrasion, and the Scripps wooden stairs collapsed, necessitating their closure for public safety.

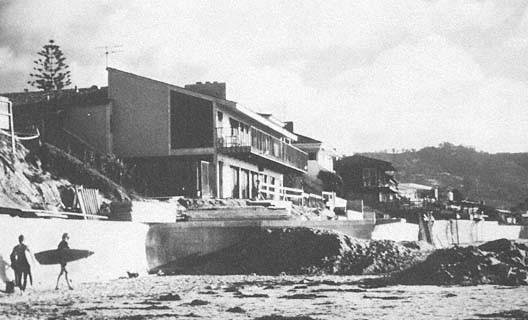

Figure 74f

October 1979 view at the same location. Victory achieved at a considerable expense: an almost

continuous seawall constructed along the cliffs.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 75

View of the recently constructed Marine Biology Building at SIO, 1979. Note that the cliff

had retreated approximately fifty-six feet since 1912.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

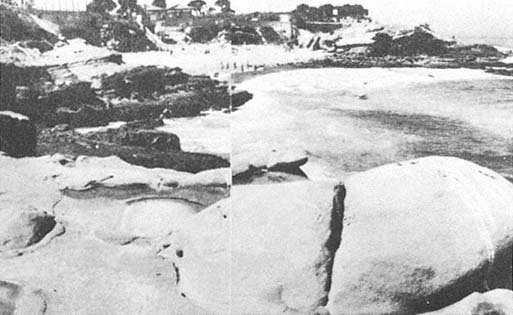

Figure 76

The unmodified lagoon shoreward of the La Jolla Submarine Canyon as it appeared in 1930.

Photo : F. Shepard Collection.

One of the last sections to be protected by a seawall was the Marine Biology Building at Scripps (fig. 75). This was a sore point with university architects who located the building on a low terrace of alluvium, about fifteen feet from its cliffed margin. They apparently failed to utilize studies showing that this margin had retreated some fifty-six feet over a sixty-three-year period from 1912 to 1975 (Hannan 1975). They even graded the outer terrace, which added to the erosion potential, and allowed pipes that drained water from the laboratories of the building to run out under the building margin, which only further eroded underlying semiconsolidated rock formations. The results should have been anticipated. The terrace margin was cut away during the first year the building was occupied, and serious sagging of the floor occurred. A seawall was then built, and other measures were taken to prevent further damage to the new building. Just north of the building, over fifty Indian burial sites have been uncovered in the cliffs. Carbon-14 dating shows them to be from 5,460 to 7,370 years old (Shumway et al. 1961). A fossil horse bone found directly south of the building yielded an age of 55,000 years as determined by amino acid (Bada et al. 1974).

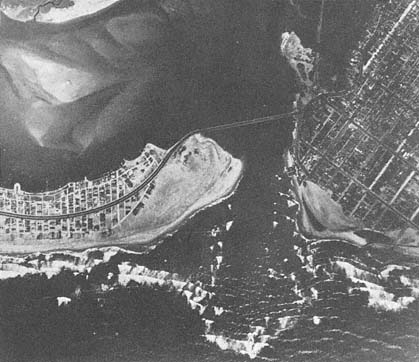

A curiosity observed in the beach north of Scripps Institution pier is the long, concretionary rock extending out from the shore. It forms a sort of dike that is well exposed each winter, when the sand is cut away from either side. Photographs dating back to 1943 show that erosion has gradually removed the outer portion of the concretion and, as blocks became detached, they were ground into sand (Emery and Kuhn 1980). South of the alluvial cliff zone is a barrier beach. It continues for more than half a mile, where it terminates south of the beach club in the sandstone cliffs. There is evidence that a considerable lagoon once existed inside this barrier, as indicated from soil foundation cores and from the fact that the lower part of the old lagoon became submerged in heavy rains (fig. 76). Extensive artificial infilling occurred during the recent dry decades, and a portion of what is now known as La Jolla Shores was created. This lagoon was partly filled by the runoff from Hidden Valley. There are

Figure 77

January 1949 photo of waves breaking against the Marine Room, La Jolla

Shores. Much more extensive damage occurred during the

stormy winter of 1982–83.

Photo : F. Shepard.

Figure 78

Locations of the La Jolla and the Scripps Submarine Canyons offshore at La Jolla, and their

relation to the land canyons. From Shepard and Emery 1941.

indications that at one time a barrier also existed at a somewhat higher level, to the north, as can be observed by the small terrace level when following the road south from Scripps Institution. The Marine Room Restaurant at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club was damaged by several storms in the 1940s (fig. 77) and sustained extensive damage again in 1983.

Submarine Canyons off La Jolla

The La Jolla coast is somewhat unique in having two submarine canyons that extend virtually in to the beach (fig. 78). One of these canyons is located off the cliffs north of Scripps Institution, and the other is off the south end of the long beach at La Jolla Shores. Both canyons are rather clearly related to the land valleys at their heads. The northern one, Scripps Canyon, extends southward in an almost straight line and has vertical, and even overhanging, walls all along its length for about a mile out, where it joins the less precipitous La Jolla Canyon. One unique feature of Scripps Canyon is its constantly changing depths. It fills gradually for a number of feet, and then a slide, sometimes combined with a turbidity current, carries the sediment seaward, often with enough force to remove large boulders along its course. It has several side canyons at its head and, from time to time, new or old buried tributaries are apparently uncovered, which may subsequently be refilled.

La Jolla Canyon has steep sides and a vertical headwall but is generally less precipitous than Scripps Canyon. It extends for thirty-three miles seaward in a general southwest direction and enters San Diego Trough twenty-seven miles off the coast at a depth of 3,600 feet. Dives into the head of the canyon show it to be unstable, and the character of the bottom changes at frequent intervals of time. The surrounding terrace has yielded many artifacts, some dated at approximately 4,200 years old. There is substantial evidence that the head has been retreating shoreward at an average rate of about one inch per year for the past few thousand years (Shepard and Dill 1966:57–58). Shepard and Dill (1966) also showed that the retreat from 1950 to 1964 was over two feet

Figure 79

View looking south toward La Jolla Shores, 1978. Note that the

rip currents can be seen in the center of the photo. They form

between the lowest and the highest waves near the La Jolla

Submarine Canyon.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 80

Sea cliff retreat by removal of the joint blocks of the sandstone bed in the lower-middle Eocene Ardath

shale that caps a bench projecting from the sea cliff 300 feet north of SIO pier; the top is about seven feet

above high-tide level. The sequence of retreat at the edge of the sandstone capped bench: July 1940, May

1944, June 1953, and July 1979. Maximum retreat was twenty-three feet in forty years, but none of the

blocks remain at the foot of the bench front. From Emery and Kuhn 1980.

per year. An interesting feature of La Jolla Canyon is the effect it has on the waves on the long beach at La Jolla Shores. The waves are almost always much smaller at the head of the canyon, owing to wave divergence as the crests move shoreward up the canyon. Conversely, they are much larger at the north end of the beach where the waves converge, so there may be two-foot breakers at the canyon head and ten-foot breakers in the northern convergence, half a mile up the beach. Thus, swimming is easier at the canyon head, and huge numbers of bathers swim there every day in the summer, whereas surfers are relegated to the northern convergence, where they abound. The effects also relate to the rip currents which are an ever-present danger. These rips are in the area between the lowest and highest waves, and the lifeguards are on constant alert for unwary bathers in this zone (fig. 79).