The Struggle for Moral Authority in Cotabato

With the political arena so narrowly circumscribed by the authoritarian state regime in the early 1980s, the counterelite alliance confronted the datu establishment in cultural arenas, disputing their right to exercise moral authority over Cotabato's Muslims. The challenge to traditional moral authority was extended incrementally by the newly active

ulama in the form of recommended alterations to accepted local practices. Recognizing that the proposed reforms were an attempt to undermine the core of the myth of sanctified inequality—the axiom that as direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad moral authority was constituted only in them—datus countered with an intensified traditionalism. While this ideological struggle was waged over the right to command the faithful, voices from Campo Muslim reveal that Muslim subordinates often held independent opinions and acted upon them.

In Campo Muslim, contestations occurred in three cultural arenas: religious ritual, popular culture, and adjudication; disputes in the first two arenas concerned ritual and celebratory activities surrounding two very important life crises: weddings and funerals. In Campo Muslim in 1985, I found that certain core Islamic practices—fasting during the month of Ramadan, strict abstention from pork, ritual circumcision of males, and the virtual absence of apostasy—had existed prior to the emergence of the ustadzes and were little affected by them. Other areas of religious practice and personal behavior had undergone appreciable change that community members agreed was entirely positive. In the estimation of residents, the attendance of male community members at Friday congregational worship had increased and a greater number of individuals were attentive to daily prayers. Incidents of public drinking and gambling by community residents had apparently declined. Certain other beliefs and practices—particularly those concerning spirits and magic—had yet to be addressed by religious reformers.

But some aspects of the cultural life of Campo Muslim were strongly (though not always loudly) contested. These were cherished (and usually well-established) practices that the ulama wanted to modify or eliminate. One contested area concerned traditional mortuary rituals. As with other Islamic peoples in Southeast Asia (see, e.g., Bowen 1993), Muslims in Cotabato have added local accretions—involving additional prayers, the use of incense, and ritual ablutions at the grave site—to the conventional Islamic burial service. The ustadzes strongly disapproved of these practices as adulterations. More highly contested were the extended death commemoration rituals—the most important funerary ceremonies in the community. In common with a number of other Southeast Asian societies—both Islamic and non-Islamic—traditional belief requires propitiation ceremonies for the deceased at intervals of 3, 7, 40, 100, and 365 days after death. In Cotabato, these ceremonies take the form of ritual meals (kanduli ) at which prayers (duwa; in Arabic, du'a ) are recited for the deceased.[17] In the

most traditional form of the kanduli, ritual specialists (panditas ) chant the prayers in a version of the Sufi tahlil , or prayer litany (Reid 1984), in which the first words of the confession of faith, "La ilaha ilia Allah" (There is no god but God), are recited repeatedly at various tempos accompanied by the swaying of the body from side to side. The rhythmic voices and movement produce a peaceful, entrancing effect in participants and listeners.

After initially objecting to all such propitiation ceremonies for the deceased, the ustadzes later modified their position and condoned the third day (telu a gay ) death commemoration ceremony. They have nonetheless strongly criticized further ceremonies as ritually improper and wasteful of resources and disapprove of the traditional Sufic content of the kanduli. The economic argument of the ulama, that extended death commemorations were unduly expensive, pertained to customary ritual practice prior to 1972. Ritual feasts before that time involved very substantial costs for the relatives of the deceased, and it was not unusual for individuals to incur major debts as a consequence of sponsoring such feasts. Since 1972 the expenses associated with death commemorations had been substantially reduced (without a concomitant reduction in the number of commemorations) as the result of moderations in the scale of ceremonies necessitated by the calamitous economic losses of that period.

The ustadzes' strong disapproval of extended death rituals distressed many ordinary Muslims, who worried about losing the means to ensure that the spirits of their dead relatives were at peace. One community elder expressed the general uneasiness of many residents at the pronouncements of the ustadzes: "First they said that traditional [religious] practices would remain. Then they announced that they would all be removed, then that only some would be kept. People are confused." Trading on this unease, traditional elites took the lead in defending traditional practices as integral aspects of Magindanaon culture and accused the ulama of extremism in their efforts at religious reform. The comments of Datu Adil are representative of their assertions:

Our elders had a saying: "Amayngka madakel niya a ulama nakauma, a magkapir tanu [When many clerics come among us we will become unbelievers]." Before [the emergence of the ulama], I didn't know what this meant, but now I do. It means that the ulama cause trouble. If one hundred clerics return to the Philippines [from studying in the Middle East], one hundred different translations of Islam will develop.[18]

The ulama are trying to destroy our culture. They are influenced by Saudi Arabia, and the Saudi government is controlled by Wahhabis.[19] Wahhabis are not Sunnis [the major sect of Islam, to which belong virtually all the Muslims of Southeast Asia] . . . According to the ustadzes, the death commemoration is not allowed, but it is a beautiful practice . . . What has happened now is that, on the seventh day after a death, people report that they hear the voice of the deceased crying; "I am hungry, give me food." I have been told about one case where the ghost of the deceased appeared, and ran after an ustadz.

Despite the misgivings of ordinary Muslims and the active resistance of datus, the number of extended death rituals beyond seven days after a death seems to be declining. Of the ten or twelve death rituals I attended or was told about during my stay in Cotabato City, only two occurred later than seven days following a death—one at one hundred days and the other at one year. Both were held by datu families, and both included traditional tahlil chanting, which is also becoming less common. At most of the kandulis I attended, traditional chanting did not occur. In general, only relatively wealthy datu families—those most anxious to counter the influence of the ustadzes and best able to afford the expense—continued to hold the full range of traditional death celebrations. It is an ironic development, though not a surprising one in light of the history of Cotabato datus in the modern period, that those who have most energetically defended traditional religious ceremonies have also been the most thoroughly Westernized.

Implicit in the assertions of traditional elites about the religious reforms of the clerics is that they deprive local Muslims not only of cherished cultural meanings but of occasions for celebration. That implication seems justified when the range of attempted reforms is examined. The traditional celebrations (common throughout Muslim Southeast Asia) associated with two holy days—Maulid en Nabi (the birthday of the Prophet—Arabic Maulidu'n-Nabi) and the Layatul Kadir (the Night of Power—Arabic Lailatu'l-Qadr) have been de-emphasized or simplified due to the influence of the ustadzes. They have also discouraged elaborate celebrations for those returning from the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj). Additionally, clerics strongly disapproved of at least three indigenous cultural activities that were particularly enjoyed by young people. One concerns the death vigil traditionally kept by family, friends, and neighbors for seven nights after the death of a community member. Although the body (in accord with standard Islamic practice) is normally buried within twenty-four hours, it is be-

lieved that the spirit of the deceased remains at the family house for seven days and requires company. The vigil was an important social occasion for adolescent girls and boys, who stayed awake the entire night playing cards, mah-jongg, and other group games, occasionally even gambling for money stakes. A passage from my field notes describes one such vigil: "Tonight I attended a vigil for Kasan's mother. About twenty young people, most of them boys, played cards for pieces of candy. Two separate card games were in progress and the noise level was quite high. Kasan's brother-in-law had to hush them twice because of the Qur'an reading going on in the back room. There three imams read separate sections of the Qur'an simultaneously. The goal is to have the Qur'an recited completely once, and ideally twice, during the seven-day vigil."

The second activity, known as panguyaw , occurred on a wedding night. It was a postwedding parlor game in which the groom playfully pursued the bride around a sitting room to the noisy encouragement of the unmarried female friends of the bride. On the occasion I witnessed, the unmarried friends of the bride and groom gathered after the wedding ceremony at the house where the bridal chamber was located. As photographs were being taken, the young female friends of the bride encouraged the groom to show affection to his new wife by putting his arm around her, holding her hand, or kissing her on the cheek. The young spectators would shriek with glee when he complied with their requests. These popular practices have by no means been eliminated by the objections of the ustadzes, but clerical disapproval has clearly decreased their incidence and social intensity.

The third offending activity was an innovative form of indigenous popular entertainment first developed during the rebellion. The dayunday ("song duel") is an exceedingly popular form of public entertainment most often found in association with wedding celebrations. It is a modern adaptation of a traditional song form using Western instruments (guitar) and some aspects of Western showmanship, yet is still unmistakably an indigenous non-Western entertainment.[20] The dayunday involves a song contest between a man and a woman, or more commonly a three-way competition between two women and one man (or vice versa), with the singers trading off extemporaneous verses of romantic repartee. Dayunday singers are professional entertainers hired most commonly to perform at wedding celebrations. Ordinary Muslims would walk miles to attend dayunday performances that typically continued throughout the night.

9.

A wedding procession near Campo Muslim. The bride,

with head bowed as prescribed by custom, is accompanied

by female attendants holding decorated umbrellas.

The ustadzes were offended by the dayunday and campaigned without success to ban it. They objected to men and women performing together and singing openly about love and romance. They claimed that dayunday performances encouraged unlawful sexual relations and elopements. Dayunday lyrics express sexual attraction indirectly, employing deep metaphors and archaic language.[21] Stage gestures—winks, nods, and nudges—depict flirtatiousness without being sexually suggestive. The overt sexual content found in the Western movies and music so pervasive in Cotabato City is entirely absent in dayunday performances. The ustadzes nevertheless attacked the dayunday more frequently and vehemently than they objected to Western entertainments because they viewed the dayunday as a pernicious cultural departure. It represented a revitalization (and, to some extent, a Westernization) of traditional popular culture at a time when the ulama were attempting to refashion social behavior to conform with the tenets of Islam. As an indigenous development it was more troubling than fully external influences because it represented a cultural drift directly away from the politico-religious project of the ulama. When it became clear that their denunciations had done nothing to lessen the popularity of

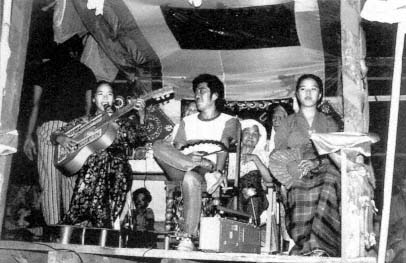

10.

A 1988 dayunday performance in Campo Muslim. This public performance,

given by three professional dayunday singers in conjunction with a wedding celebration,

lasted from dusk till dawn and was attended by hundreds of community residents.

the dayunday, many ustadzes simply refused to attend weddings where the dayunday was performed. As clerics condemned dayundays, datus embraced them. Traditional elites sponsored every one of the dayundays I attended and, with the resumption of electoral politics in 1985, they became the most popular way to ensure large crowds at political rallies.

Another major area of cultural contention between clerics and traditional elites was adjudication. Datus pointed to instances of the austere application of Islamic law by certain clerics as evidence for ulama judicial extremism, as opposed to the more flexible penalties associated with traditional Magindanaon jurisprudence, where religious and social transgressions were "cured" by fines. During the latter part of the rebellion and in the years following the cease-fire, corpses (most often of females) would regularly be found floating down the Pulangi River from areas under rebel control. During my stay in Cotabato City fishermen still occasionally retrieved corpses from the river. It was widely accepted that these were the bodies of individuals punished for unlawful sexual relations by particularly strict ustadzes operating with the rebel forces. Many Muslims were troubled by this evidence of severe

compliance with the dictates of Sharia law, because it represented a serious escalation from the fines and forced marriages or beatings traditionally imposed for such transgressions. A story told by Datu Adil about one of his acts of adjudication illustrates the differences between traditional customs and the presumed adjudication practices of the MILF:

A man who was married with four children eloped with a woman to Davao. A party with guns was sent after him. The couple came to me in the middle of the night and asked me to help them. The man said: "I am a traveling insurance salesman, and while I was traveling I met this young woman and fell in love and we eloped." She was related to the Nuling datus, and ten years younger than the man. Her father was my friend. That was why they came to me.

When the parents of the woman heard of my involvement they asked that the distribution of the bantingan [bridewealth] be held at my house and the wedding at their place. The bridewealth was seven hundred pesos. I fined the man three hundred pesos. I could have taken the whole fine for myself but I distributed most of it. They were in trouble when they came to me. The girl's parents had contacted Hadji Murad and the MILF was looking for them. The man would probably have been killed.

Despite stories such as these, and the clear evidence of a certain number of incidents of harsh punishments meted out by members of the "inside" ulama, the majority of MILF adjudicators reportedly did not dispense legal decisions resulting in penalties that were significantly different from those traditionally imposed. The reason most often given for their leniency was that local Muslims were not yet genuine Muslims and so did not deserve strict Islamic sanctions.