The Rise of an Independent Ulama and Islamic Renewal

I closed the previous chapter by noting that the Cotabato rebel leadership regained popular support in the early 1980s with the assistance of Islamic teachers, who had begun to play an increased public role. Here I trace the emergence of Islamic clerics in Cotabato whose religious and political views differed sharply from those of the datu establishment.

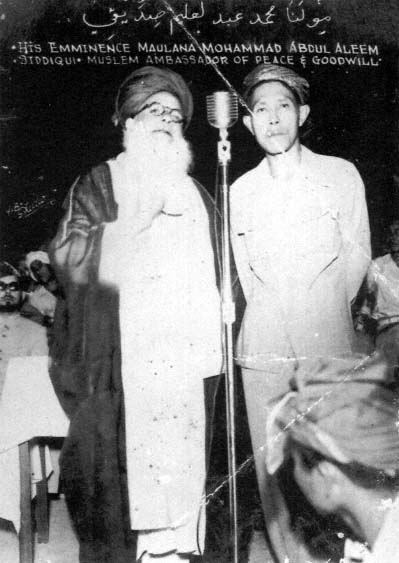

The history of the modern ulama in Cotabato dates from 1951. That was the year Maulana Mohamed Abdul Aleem Siddiqui, an Egyptian missionary, visited Cotabato City. According to Imam Akmad, the head imam at the Campo Muslim mosque, the Maulana was the first alim to have arrived in Cotabato in his lifetime. Imam Akmad and his wife vividly remember that short visit:

The Maulana gave a speech in the city plaza during his visit. He spoke in Arabic, which was translated into English and then into Magindanaon.[3] During the speech there were rain clouds approaching, but the Maulana told the crowd not to worry about them. When he finished his speech he walked to his hotel and the rain clouds were right at his back. As soon as he entered the hotel rain began to fall in torrents, causing flooding in the city.

The Maulana held a public debate with a Catholic priest in Buluan. After that debate the priest removed his crucifix and threw it in the river.

8.

Photograph commemorating the 1951 visit of Maulana Mohammad

Abdul Aleem Siddiqui (left) to Cotabato. The Maulana, the first Middle

Eastern Muslim missionary to visit Cotabato in the modern era, is pictured

here in the city plaza, accompanied by an unidentified Magindanaon datu.

The Maulana went from house to house in Muslim communities in the city to urge the men to come to Friday noon prayers. He was also the first person ever to instruct women to wear hijab [head coverings] in the mosque.

In 1952, the first resident Islamic missionary in local memory arrived. As Ustadz Ali recalled, "In 1952, a missionary from al-Azhar was sent here—Abdul Ghani Sindang, an Indonesian. He remained here in Cotabato for more than four years and was the first Islamic teacher ever to be called ustadz.'"[4] Ustadz Sindang arrived in the Philippines in 1950 along with another missionary from al-Azhar. Their first school in Malabang closed within a year and Sindang proceeded to Cotabato City (Muslim Association of the Philippines 1956, 106). He is almost certainly the same missionary referred to by Hunt in his brief account of Muslim religious education in Cotabato in the early 1950s: "In 1950, a formal Islamic school was set up in Cotabato, housed in a residence donated by a local datu and headed by a Muslim missionary sent by the Egyptian government. In addition to learning to read the Qur'an in Arabic, the students are taught to understand the language" ([1957] 1974, 205). Imam Akmad remembers the first ustadz born in Cotabato: "The first local ustadz was Ustadz Hadji Salik Badruddin. He returned from Saudi Arabia after World War II, in the 1950s. He founded the Nakdah [a madrasah] in Mabini."

As these accounts illustrate, the emergence of a new ulama in Cotabato resulted from the reestablishment of ties with Islamic religious centers after World War II, and an unprecedented intensification of ties with al-Azhar University in Egypt. The Islamic scholars who returned from al-Azhar were regarded collectively as a new species of religious specialists and were addressed by the new title "ustadz." Before the 1950s, religious teachers were usually referred to by the non-Islamic term (of Sanskrit origin) "guru." The aims of religious education also began to be altered with the growth of madrasahs headed by missionaries and, eventually, by local al-Azhar graduates. Prior to the development of madrasahs, religious education took place at the home of the guru and had as its goal the reading and memorization—but not the translation or interpretation—of the Holy Qur'an. This traditional Islamic education was widespread but very rudimentary; the great majority of students studied just two or three years, and those who studied longer were still rarely able to understand what they read.[5] The low level of religious education was reflected in Friday services. Pas-

sages read from the Qur'an were not typically translated and genuine khutbah (commentaries based on the passages read) were rarely given.

By contrast, the new madrasahs emphasized the understanding of Arabic and the textual exegesis of the Qur'an. Instruction at the secondary level has come to include courses in Islamic History, Exegesis (Tafsir), and Tradition of the Prophet (Hadith), all taught primarily in Arabic. The advancement of Islamic education altered contemporary religious services. Qur'anic passages are now almost always translated and regularly commented upon in khutbahs by ustadzes. The transformation of religious services eventually came to include changes in the political arrangements associated with community prayers. By tradition—one reinvigorated in the postwar economic boom in Cotabato—community mosques were endowed, sustained, and controlled by local datus. As we have seen (and as indicated in the passage from Hunt just quoted) datu sponsorship extended to religious schools as well (Hassoubah 1983). Under traditional arrangements, in place as recently as the late 1970s in some areas, Friday assembly prayers would not begin until the arrival of the datu or his representative. The imam (prayer leader) of the mosque paid his respects first to the datu, who sat at the very front of the congregation, before beginning the service. Imams were considered functionaries of the ruling datu and, in most cases, belonged to datu families.

The close association between nobility and religious leadership gradually began to weaken with the emergence of the ulama. For one, clerics used Friday sermons to advance an alternative, egalitarian ideology as part of their program for Islamic renewal.[6] The following passage from my field notes illustrates the use of Friday sermons to emphasize equality and social justice in Islam. The passage paraphrases the contents of a Friday sermon given by Ustadz Ali in Campo Muslim:

The sermon given today by Ustadz Ali concerned the true meaning of being a Muslim. His talk was based on the ayah [Qur'anic verse] "Do not die until you become a Muslim." He stated that to become a Muslim one must act like a Muslim at all times. Behaving like a Muslim consists of much more than merely praying and fasting. It means practicing social justice.

He related a story about Caliph Ali. Ali was involved in a legal dispute with a non-Muslim and both parties went before a qadi (Islamic jurist) to resolve the matter. When Ali entered the hearing room the qadi received him with lavish servility. When the non-Muslim arrived the qadi acknowledged him brusquely. Ali became quite angered at this behavior

and reminded the qadi of his duty to dispense justice and treat all men equally before the law.

Imam Akmad put such messages in perspective in the course of discussing changes in the office of imam: "The institution of imam has existed from the time of the Prophet. Here [in Cotabato] it was believed that the imam had to be from the datu class because he needed to be a strong man. If he did not belong to a datu family it was thought that there would be punishment from God. This changed when the ustadzes came. They said: 'There are no differences among people in the eyes of God.'"

In one of my conversations with Ustadz Ali, he commented on the claim of traditional elites to politico-religious leadership on the basis of descent from the Prophet Muhammad:

The ustadzes do not like such claims. Muhammad did not appoint his successor. He did not believe in blood relatedness as the criterion for leadership. The blood relation of the caliphs to Muhammad was a distant one. What the ustadzes want to see are honorable leaders, trusted leaders, not leaders chosen solely on the basis of blood inheritance. We are not attempting to do away with the role of descent. We do not deny the tarsilas [genealogies]. But we do try to support the good datus. To attempt to remove the datus would create difficulties. The issue of noble inheritance is a problem we have long had. Good people with good minds have had little chance if they were not royal descendants. We cannot remove the problem of inheritance overnight. It must be a gradual process.

The ideological project of the ulama, advanced at Friday sermons and other public forums, did not directly challenge the myth of sanctified inequality as inscribed in the tarsilas. It did not deny the existence of a nobility, for such a frontal assault on the core element of the ideology of traditional rule would have alienated them from potential supporters (including, in some cases, their relatives) as well as invite the ire of powerful political figures. Instead, they disputed the claim that nobility was the single criterion for politico-religious leadership. This argument was presented in a gradual and indirect manner by emphasizing populist aspects of Islamic doctrine and by supporting "good datus"—those few who meet the ulama's criteria for Islamic leadership.

The connection between nobility and religious leadership has also been interrupted by the increasing availability of alternative sources of funding for religious purposes. External funds arrived first in the form of the scholarships from the government of Egypt in the 1950s, a flow

that expanded rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s. Virtually all the later funding came about as a direct consequence of the armed struggle during the 1970s. As early as 1971, the Libyan government provided funds for mosque and madrasah construction, and in 1978 the Organization of the Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers (OIC) dispensed funds for the building of thirteen new mosques in the South and the repair or expansion of a great number of mosques and madrasahs (Majul 1985). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia also contributed (and continues to provide) financial support for various religious projects. Middle East governments have provided missionaries to the Muslim Philippines since the 1950s, and Egypt continues to send teachers for one- or two-year assignments in Cotabato. More significantly for the development of an independent local ulama, the governments of Libya and Saudi Arabia began to support a small percentage of local ulama as long-term missionaries. Ustadz Ali received a small salary from the government of Libya.

Since the late 1970s, significant additional funding has come from private institutions and individuals in the Middle East through contacts developed by both the Muslim separatist rebels and local ulama. The Mahad al-Ulum al-Islamia in Campo Muslim has been the beneficiary of such funding. The Mahad, when it was founded in late 1979, relied at first on local funds alone but soon obtained external financial support from private donors in Saudi Arabia. As a result, it rapidly expanded, even adding an English program.[7] Today the Mahad, with more than four hundred students in its Arabic program, is one of the largest Islamic schools in the Philippines and attracts students from all the southern provinces. With its well-constructed two-story buildings and its large cemented courtyard, it is far and away the most impressive establishment in Campo Muslim.

Before moving on, let me reemphasize a point made previously. While their origins may be traced to the early 1950s, it is not accurate to speak of the ulama as a significant religious force before 1980. Despite the accelerated construction of mosques and establishment of madrasahs in the 1950s and 1960s, there is reason to doubt claims (see, e.g., Bauzon 1991; Gowing 1979) for any substantial advancement in Islamic education or orthopraxy prior to that year. In an extensive survey conducted in Muslim Mindanao in 1980, Hassoubah found that "madrasah graduates [were] still unable to use the Arabic language with proficiency" (1983, 74).[8] In respect to religious orthopraxy, Islamic observance for the large majority of Cotabato Muslims

prior to 1980 resembled, with local modifications, that described for ordinary Muslims in other parts of the southern Philippines and in much of the rest of Islamic Southeast Asia (see, e.g., Kiefer 1972; Fraser 1960; Djamour 1959). While there was strict compliance with certain aspects of Islamic doctrine, alcohol use and gambling were widespread, Arabic prayers seldom understood, beliefs in spirits common, Qur'anic education extremely rudimentary, and mosque attendance slight.

The principal reason for the absence of substantial Islamic renewal prior to the 1980s despite the presence of reform-minded clerics was a lack of opportunity. While numbers of Middle East-educated clerics returned to the Philippines in the late 1960s, they were almost immediately engulfed in the armed conflict of the 1970s. It was nearly 1980 before conditions existed that allowed local ustadzes to teach and preach unconstrained by datu influence or military harassment. When they finally spoke out publicly, they not only promoted an Islamic populism but strenuously championed the reform of particular cultural practices. As we shall see, those efforts at religious reform have been the source of some contention in Campo Muslim and throughout Cotabato.

In 1985–86, the ustadzes of the Mahad provided services to their host community that were for the most part limited to spiritual guidance and religious education. Although located in Campo Muslim, the Mahad was not altogether a part of it. The relative elegance of its structures contrasted with the plainness and poverty of the rest of the community. The Mahad was built in Campo Muslim but never primarily intended to serve community residents. While it was not unusually expensive, most families in Campo Muslim could not afford the tuition to send their children to the Mahad and, while I lived there, very few scholarships were available to community residents. An observer standing in the main road of the community could easily discern this in the busy two-way morning traffic, as students from relatively more affluent locales within and outside the city entered Campo Muslim to attend the Mahad, while most Campo Muslim children left the community to attend public, state-run schools.

The lack of engagement of the local ulama with the immediate and material problems of the community may be partly explained by limited resources. Unlike Christian educational and charitable organizations, the ulama possessed no linkages to international community development organizations. According to Ustadz Ali, the private overseas

donations received by the Mahad carried spending restrictions that tied their use to narrowly defined religious purposes. A second factor was that most of the local ulama lacked experience with nonreligious community affairs and paid limited attention to the pressing economic problems of the community. Most had no education in, or practical experience with, community development. At least one influential ustadz expressed his awareness of this shortcoming. After certain of the local ulama accused Nur Miskin, a student activist, of being, alternatively, a Sbia[9] or a communist, he went "inside" to talk with Ustadz Salim, the highest-ranking cleric in the Cotabato rebel leadership. On hearing of the accusations, Ustadz Salim commented, "Da pan ustadz siya" (There are no ustadzes here yet), by which he meant that local ustadzes had yet to attain the knowledge he thought an ustadz should have. Ustadz Salim added that many young ustadzes knew nothing about community problems and needed to be educated about those problems and their causes.