Chapter 9

Unarmed Struggle

The political configuration of Campo Muslim is uncommonly accordant with its physical arrangement. The community faces the Pulangi River and the riverside thoroughfare leading to the center of the city. On that road, directly opposite the main entrance to Campo Muslim, lies the large house of Datu Kamsa, the barangay captain (see map 4). Traditional and modern bureaucratic authority merge in the person of Datu Kamsa. Together with his barangay council, composed mostly of elder datus, he adjudicates community disputes in much the same manner as his precolonial predecessors. As a government functionary, he also implements state policies in the community (to the extent he is able) and coordinates the government assistance infrequently provided to Campo Muslim.

An unpaved main road bisects Campo Muslim, running perpendicular to the paved riverside road. The forepart of the community, that closest to the river and the barangay captain, is very densely populated. Here, behind the buildings lining either side of the main road, the crowded and partially flooded interior (sa lusud) residential areas are found. Farther down that road, houses become less tightly spaced, and small rice fields appear. By the section of road farthest from the Pulangi River, the community assumes a nearly rural appearance. Here, away from the immediate borders of the road, rice fields and coconut trees predominate, with houses thinly distributed among them. Electricity and city water taps are scarce this far from the city road, but

Map 4.

Campo Muslim

the clamor and squalor of the forepart of the community are also mostly lacking. Here, at the end of the road, and at the edge of the community and city, lies the Mahad al-Ulum al-Islamia (known by community residents as "the Mahad"), the largest Islamic school (madrasah) in Cotabato.[1] The school was founded by Omar Pasigan, an Islamic teacher who graduated from al-Azhar University in Cairo. One of the first scholars (alim ) hired to teach at the Mahad was Ustadz Ali Abdul Ajiz Naga,[2] also a graduate of al-Azhar, and a classmate of Hashim Salamat, one of the founders of the Moro National Liberation Front. Ustadz Ali spent much of the rebellion in Cotabato City and was arrested four times by the military. He taught Arabic, Qur'anic exegesis (tafsir ), as well as other courses. At the Friday noon assembly prayer (Salatu'l-Jumah ) he often gave the sermon (khutbah ) at the mosque on the grounds of the Mahad. In those sermons he typically counseled community members to become "genuine Muslims" (tidtutidtu a Muslim) in their behavior and instructed them in the fundamentals of Islamic equality and justice. Ustadz Ali also occasionally traveled "inside" (sa lusud), to the mountain headquarters of the Cotabato rebels—a daylong round-trip journey—to attend meetings and seminars. His affinity with the rebel leadership derived from kinship and school ties with members of the "inside" ulama—those Islamic clerics who remained with the rebels in the hills or in exile abroad—as well as from his commitment to the goal of political autonomy for Philippine Muslims under Islamic governance.

The residence of the barangay captain and the Mahad demarcate the political as well as the territorial antipodes of Campo Muslim. The former is situated on the riverside road near the city center and nearby regional military headquarters, the sites of Christian ascendancy and state order. The latter sits at the edge of the community, far from the Christian core of the city and close to the place of escape; the wide, roadless floodlands lying south and west of the city proper that have sheltered so many Muslim rebels.

This chapter examines the mostly unarmed struggle waged in Cotabato from 1980 until 1986 between the political alliances expressed spatially by these polar positions in Campo Muslim. It was a struggle between Muslim contenders fought almost entirely in cultural arenas but with the same final stakes as in the armed rebellion—the right to rule Muslim Cotabato. Unlike the armed rebellion in Cotabato, it was an aboveground ideological struggle over nothing less than the moral authority to command Cotabato Muslims. For the first time in the

history of Cotabato, a consolidated Muslim counterelite challenged in public (though not traditionally political) arenas the political legitimacy of the datu establishment.

That cultural conflict is viewed here through the eyes of the Muslim subordinates who found themselves caught between the contending alliances (quite literally so in the case of Campo Muslim). While the struggle occurred to various degrees throughout Muslim Cotabato, Campo Muslim once again offers a convenient point of departure, especially insofar as the ideological contest was especially attuned to the Muslim urban masses. My main purpose in this chapter is to demonstrate the ways in which ordinary Muslims actively evaluated and responded to the ideological arguments of the two contending elite groups—arguments concerning the fundamental issues of Islamic authority and Muslim identity in Cotabato. I begin by considering a development significant for both community and regional politics: the emergence of an ulama independent of datu supervision.

The Rise of an Independent Ulama and Islamic Renewal

I closed the previous chapter by noting that the Cotabato rebel leadership regained popular support in the early 1980s with the assistance of Islamic teachers, who had begun to play an increased public role. Here I trace the emergence of Islamic clerics in Cotabato whose religious and political views differed sharply from those of the datu establishment.

The history of the modern ulama in Cotabato dates from 1951. That was the year Maulana Mohamed Abdul Aleem Siddiqui, an Egyptian missionary, visited Cotabato City. According to Imam Akmad, the head imam at the Campo Muslim mosque, the Maulana was the first alim to have arrived in Cotabato in his lifetime. Imam Akmad and his wife vividly remember that short visit:

The Maulana gave a speech in the city plaza during his visit. He spoke in Arabic, which was translated into English and then into Magindanaon.[3] During the speech there were rain clouds approaching, but the Maulana told the crowd not to worry about them. When he finished his speech he walked to his hotel and the rain clouds were right at his back. As soon as he entered the hotel rain began to fall in torrents, causing flooding in the city.

The Maulana held a public debate with a Catholic priest in Buluan. After that debate the priest removed his crucifix and threw it in the river.

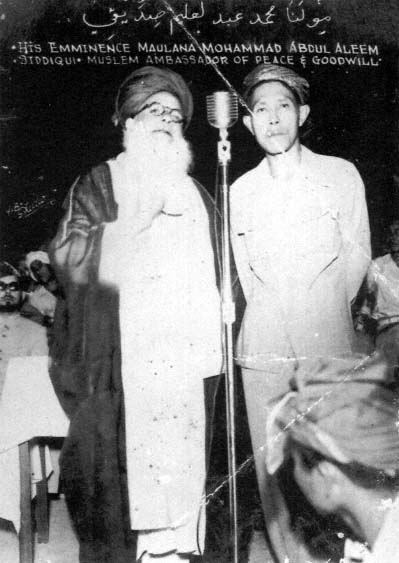

8.

Photograph commemorating the 1951 visit of Maulana Mohammad

Abdul Aleem Siddiqui (left) to Cotabato. The Maulana, the first Middle

Eastern Muslim missionary to visit Cotabato in the modern era, is pictured

here in the city plaza, accompanied by an unidentified Magindanaon datu.

The Maulana went from house to house in Muslim communities in the city to urge the men to come to Friday noon prayers. He was also the first person ever to instruct women to wear hijab [head coverings] in the mosque.

In 1952, the first resident Islamic missionary in local memory arrived. As Ustadz Ali recalled, "In 1952, a missionary from al-Azhar was sent here—Abdul Ghani Sindang, an Indonesian. He remained here in Cotabato for more than four years and was the first Islamic teacher ever to be called ustadz.'"[4] Ustadz Sindang arrived in the Philippines in 1950 along with another missionary from al-Azhar. Their first school in Malabang closed within a year and Sindang proceeded to Cotabato City (Muslim Association of the Philippines 1956, 106). He is almost certainly the same missionary referred to by Hunt in his brief account of Muslim religious education in Cotabato in the early 1950s: "In 1950, a formal Islamic school was set up in Cotabato, housed in a residence donated by a local datu and headed by a Muslim missionary sent by the Egyptian government. In addition to learning to read the Qur'an in Arabic, the students are taught to understand the language" ([1957] 1974, 205). Imam Akmad remembers the first ustadz born in Cotabato: "The first local ustadz was Ustadz Hadji Salik Badruddin. He returned from Saudi Arabia after World War II, in the 1950s. He founded the Nakdah [a madrasah] in Mabini."

As these accounts illustrate, the emergence of a new ulama in Cotabato resulted from the reestablishment of ties with Islamic religious centers after World War II, and an unprecedented intensification of ties with al-Azhar University in Egypt. The Islamic scholars who returned from al-Azhar were regarded collectively as a new species of religious specialists and were addressed by the new title "ustadz." Before the 1950s, religious teachers were usually referred to by the non-Islamic term (of Sanskrit origin) "guru." The aims of religious education also began to be altered with the growth of madrasahs headed by missionaries and, eventually, by local al-Azhar graduates. Prior to the development of madrasahs, religious education took place at the home of the guru and had as its goal the reading and memorization—but not the translation or interpretation—of the Holy Qur'an. This traditional Islamic education was widespread but very rudimentary; the great majority of students studied just two or three years, and those who studied longer were still rarely able to understand what they read.[5] The low level of religious education was reflected in Friday services. Pas-

sages read from the Qur'an were not typically translated and genuine khutbah (commentaries based on the passages read) were rarely given.

By contrast, the new madrasahs emphasized the understanding of Arabic and the textual exegesis of the Qur'an. Instruction at the secondary level has come to include courses in Islamic History, Exegesis (Tafsir), and Tradition of the Prophet (Hadith), all taught primarily in Arabic. The advancement of Islamic education altered contemporary religious services. Qur'anic passages are now almost always translated and regularly commented upon in khutbahs by ustadzes. The transformation of religious services eventually came to include changes in the political arrangements associated with community prayers. By tradition—one reinvigorated in the postwar economic boom in Cotabato—community mosques were endowed, sustained, and controlled by local datus. As we have seen (and as indicated in the passage from Hunt just quoted) datu sponsorship extended to religious schools as well (Hassoubah 1983). Under traditional arrangements, in place as recently as the late 1970s in some areas, Friday assembly prayers would not begin until the arrival of the datu or his representative. The imam (prayer leader) of the mosque paid his respects first to the datu, who sat at the very front of the congregation, before beginning the service. Imams were considered functionaries of the ruling datu and, in most cases, belonged to datu families.

The close association between nobility and religious leadership gradually began to weaken with the emergence of the ulama. For one, clerics used Friday sermons to advance an alternative, egalitarian ideology as part of their program for Islamic renewal.[6] The following passage from my field notes illustrates the use of Friday sermons to emphasize equality and social justice in Islam. The passage paraphrases the contents of a Friday sermon given by Ustadz Ali in Campo Muslim:

The sermon given today by Ustadz Ali concerned the true meaning of being a Muslim. His talk was based on the ayah [Qur'anic verse] "Do not die until you become a Muslim." He stated that to become a Muslim one must act like a Muslim at all times. Behaving like a Muslim consists of much more than merely praying and fasting. It means practicing social justice.

He related a story about Caliph Ali. Ali was involved in a legal dispute with a non-Muslim and both parties went before a qadi (Islamic jurist) to resolve the matter. When Ali entered the hearing room the qadi received him with lavish servility. When the non-Muslim arrived the qadi acknowledged him brusquely. Ali became quite angered at this behavior

and reminded the qadi of his duty to dispense justice and treat all men equally before the law.

Imam Akmad put such messages in perspective in the course of discussing changes in the office of imam: "The institution of imam has existed from the time of the Prophet. Here [in Cotabato] it was believed that the imam had to be from the datu class because he needed to be a strong man. If he did not belong to a datu family it was thought that there would be punishment from God. This changed when the ustadzes came. They said: 'There are no differences among people in the eyes of God.'"

In one of my conversations with Ustadz Ali, he commented on the claim of traditional elites to politico-religious leadership on the basis of descent from the Prophet Muhammad:

The ustadzes do not like such claims. Muhammad did not appoint his successor. He did not believe in blood relatedness as the criterion for leadership. The blood relation of the caliphs to Muhammad was a distant one. What the ustadzes want to see are honorable leaders, trusted leaders, not leaders chosen solely on the basis of blood inheritance. We are not attempting to do away with the role of descent. We do not deny the tarsilas [genealogies]. But we do try to support the good datus. To attempt to remove the datus would create difficulties. The issue of noble inheritance is a problem we have long had. Good people with good minds have had little chance if they were not royal descendants. We cannot remove the problem of inheritance overnight. It must be a gradual process.

The ideological project of the ulama, advanced at Friday sermons and other public forums, did not directly challenge the myth of sanctified inequality as inscribed in the tarsilas. It did not deny the existence of a nobility, for such a frontal assault on the core element of the ideology of traditional rule would have alienated them from potential supporters (including, in some cases, their relatives) as well as invite the ire of powerful political figures. Instead, they disputed the claim that nobility was the single criterion for politico-religious leadership. This argument was presented in a gradual and indirect manner by emphasizing populist aspects of Islamic doctrine and by supporting "good datus"—those few who meet the ulama's criteria for Islamic leadership.

The connection between nobility and religious leadership has also been interrupted by the increasing availability of alternative sources of funding for religious purposes. External funds arrived first in the form of the scholarships from the government of Egypt in the 1950s, a flow

that expanded rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s. Virtually all the later funding came about as a direct consequence of the armed struggle during the 1970s. As early as 1971, the Libyan government provided funds for mosque and madrasah construction, and in 1978 the Organization of the Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers (OIC) dispensed funds for the building of thirteen new mosques in the South and the repair or expansion of a great number of mosques and madrasahs (Majul 1985). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia also contributed (and continues to provide) financial support for various religious projects. Middle East governments have provided missionaries to the Muslim Philippines since the 1950s, and Egypt continues to send teachers for one- or two-year assignments in Cotabato. More significantly for the development of an independent local ulama, the governments of Libya and Saudi Arabia began to support a small percentage of local ulama as long-term missionaries. Ustadz Ali received a small salary from the government of Libya.

Since the late 1970s, significant additional funding has come from private institutions and individuals in the Middle East through contacts developed by both the Muslim separatist rebels and local ulama. The Mahad al-Ulum al-Islamia in Campo Muslim has been the beneficiary of such funding. The Mahad, when it was founded in late 1979, relied at first on local funds alone but soon obtained external financial support from private donors in Saudi Arabia. As a result, it rapidly expanded, even adding an English program.[7] Today the Mahad, with more than four hundred students in its Arabic program, is one of the largest Islamic schools in the Philippines and attracts students from all the southern provinces. With its well-constructed two-story buildings and its large cemented courtyard, it is far and away the most impressive establishment in Campo Muslim.

Before moving on, let me reemphasize a point made previously. While their origins may be traced to the early 1950s, it is not accurate to speak of the ulama as a significant religious force before 1980. Despite the accelerated construction of mosques and establishment of madrasahs in the 1950s and 1960s, there is reason to doubt claims (see, e.g., Bauzon 1991; Gowing 1979) for any substantial advancement in Islamic education or orthopraxy prior to that year. In an extensive survey conducted in Muslim Mindanao in 1980, Hassoubah found that "madrasah graduates [were] still unable to use the Arabic language with proficiency" (1983, 74).[8] In respect to religious orthopraxy, Islamic observance for the large majority of Cotabato Muslims

prior to 1980 resembled, with local modifications, that described for ordinary Muslims in other parts of the southern Philippines and in much of the rest of Islamic Southeast Asia (see, e.g., Kiefer 1972; Fraser 1960; Djamour 1959). While there was strict compliance with certain aspects of Islamic doctrine, alcohol use and gambling were widespread, Arabic prayers seldom understood, beliefs in spirits common, Qur'anic education extremely rudimentary, and mosque attendance slight.

The principal reason for the absence of substantial Islamic renewal prior to the 1980s despite the presence of reform-minded clerics was a lack of opportunity. While numbers of Middle East-educated clerics returned to the Philippines in the late 1960s, they were almost immediately engulfed in the armed conflict of the 1970s. It was nearly 1980 before conditions existed that allowed local ustadzes to teach and preach unconstrained by datu influence or military harassment. When they finally spoke out publicly, they not only promoted an Islamic populism but strenuously championed the reform of particular cultural practices. As we shall see, those efforts at religious reform have been the source of some contention in Campo Muslim and throughout Cotabato.

In 1985–86, the ustadzes of the Mahad provided services to their host community that were for the most part limited to spiritual guidance and religious education. Although located in Campo Muslim, the Mahad was not altogether a part of it. The relative elegance of its structures contrasted with the plainness and poverty of the rest of the community. The Mahad was built in Campo Muslim but never primarily intended to serve community residents. While it was not unusually expensive, most families in Campo Muslim could not afford the tuition to send their children to the Mahad and, while I lived there, very few scholarships were available to community residents. An observer standing in the main road of the community could easily discern this in the busy two-way morning traffic, as students from relatively more affluent locales within and outside the city entered Campo Muslim to attend the Mahad, while most Campo Muslim children left the community to attend public, state-run schools.

The lack of engagement of the local ulama with the immediate and material problems of the community may be partly explained by limited resources. Unlike Christian educational and charitable organizations, the ulama possessed no linkages to international community development organizations. According to Ustadz Ali, the private overseas

donations received by the Mahad carried spending restrictions that tied their use to narrowly defined religious purposes. A second factor was that most of the local ulama lacked experience with nonreligious community affairs and paid limited attention to the pressing economic problems of the community. Most had no education in, or practical experience with, community development. At least one influential ustadz expressed his awareness of this shortcoming. After certain of the local ulama accused Nur Miskin, a student activist, of being, alternatively, a Sbia[9] or a communist, he went "inside" to talk with Ustadz Salim, the highest-ranking cleric in the Cotabato rebel leadership. On hearing of the accusations, Ustadz Salim commented, "Da pan ustadz siya" (There are no ustadzes here yet), by which he meant that local ustadzes had yet to attain the knowledge he thought an ustadz should have. Ustadz Salim added that many young ustadzes knew nothing about community problems and needed to be educated about those problems and their causes.

The MILF and the New Opposition Alliance

A new Muslim separatist organization, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) first announced its independent existence (as distinct from the MNLF) in 1984. The establishment of a rival Moro "liberation front" resulted from a political schism between Hashim Salamat and Nur Misuari, the chairman and vice-chairman respectively of the MNLF. The rift, which had been developing for some time, first became public in December 1977, after the collapse of the second round of talks in Tripoli, Libya, aimed at implementing the peace accord and cease-fire agreement. By 1980, the "New Leadership" (Salamat quoted in Mastura 1985, 16) faction of the MNLF had moved its headquarters to Lahore, Pakistan, and Salamat was having success promoting his leadership to international Islamic organizations and "moderate Arab states" (Mastura 1985, 15. Salamat's faction also engaged in talks with the Philippine government on reopening negotiations to implement the Tripoli Agreement. While the Misuari faction had become intransigent after the failure of the 1977 Tripoli negotiations, reverting to a separatist stance after having previously agreed to a negotiated autonomy within the framework of the Philippine republic, the Salamat faction maintained a conciliatory posture, endorsing "a peaceful resolution of differences on the issue of autonomy" (Salamat quoted in Mastura 1985, 15).

In early 1980, Salamat's group suffered a stunning political blow. Amelil Malaguiok (alias "Commander Ronnie"), the chairman of the Kutawatu Revolutionary Committee (KRC), defected to the government with a number of his field commanders and received as his prize the premier position in the newly formed regional autonomous government of Region 12, encompassing Central Mindanao. The Kutawatu Revolutionary Committee had been the largest regional unit in the MNLF, and the only one effectively controlled by the Salamat faction. Although it never recovered its momentum on the diplomatic front, the Salamat group did rebuild its command structure and regain its popular support in Cotabato. This success was due in part to the personal popularity of Hadji Murad, the man who assumed the chairmanship of the KRC (the name of which was changed at about this time to the Kutawatu Regional Committee). As we shall see, the revitalization of the KRC was also aided by the development of an aboveground political support structure. In mid-1984, six years after his "takeover" (Mastura 1985, 15) of the MNLF, Salamat officially changed the title of his organization to the "Moro Islamic Liberation Front" to "underscore Islam as the rallying point of the Bangsamoro struggle" (1985, 17). In a letter to the secretary general of the Organization of the Islamic Conference, Salamat elaborated: "All Mujahideen under the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) adopt Islam as their way of life. Their ultimate objective in their Jihad is to make supreme the WORD of ALLAH and establish Islam in the Bangsamoro homeland" (emphases in the original; 1985, 18). Salamat's principal aim of establishing Islam in Muslim Mindanao varied markedly from that of his rival, Misuari, who sought first the creation of a separate state in the Moro homeland. It is doubtful, however, whether the stated objective of the newly formed MILF was really different from the goals formulated by Salamat and the al-Azhar group twenty years earlier. The name change of the Salamat faction represented less an alteration of goals and more a recognition that, after six years of challenges to his leadership of the MNLF, Nur Misuari retained a tenacious grip as chairman. Salamat's only option was to relinquish his claim to sole leadership of the original front and develop another organization. Here it was politic to choose a name that best emphasized the differences between his new front and the original Moro National Liberation Front.

When I began my field research in 1985, the members and supporters of the Cotabato MILF faced arrest and detention without trial as

participants in an illegal armed organization. Because of that political reality, I did not question Campo Muslim residents about the activities of the MILF, nor did I seek interviews with its current members. Even so, community residents volunteered a good deal of information about the MILF and I engaged in informal and often unexpected conversations with active rebels. Nevertheless, as a result of my approach, and because the MILF operates as an underground organization, I know less about the MILF than I do about other political associations.

In 1984, the Salamat faction had undergone a reorganization before taking on a new name. In the letter quoted above, Salamat also explained that reorganization, and included the following passage: "The MILF operates as a parallel government vis-à-vis the enemy government within its area of responsibility and exercises influence extensively among the Bangsamoro masses in a degree more effective and binding than that of the enemy administration" (quoted in Mastura 1985, 18). An MILF "shadow" government did exist in Campo Muslim. A clandestine MILF barangay committee paralleled the one headed by Datu Kamsa. While I lack specifics of its day-to-day operation or influence, my impression is that, as with many other Philippine political associations, it functioned in an ad hoc and informal manner. In addition to shadow-governing offices, there were also "invisible" MILF workers, active agents who operated secretly in the city (or elsewhere away from rebel-held areas). Invisible workers kept track of developments in their areas of operation and performed other assignments, which almost certainly included the selective use of intimidation. The Kutawatu Regional Committee published a local underground news sheet, Tantawan[10] —a mimeographed bulletin written in English with some Tagalog, which appeared monthly or bimonthly. It carried editorials and reports of local incidents—particularly of armed clashes between MILF units and the military.

Although it is difficult to determine with any precision how "effective and binding" was the influence exercised by the MILF in Campo Muslim, the MILF was more influential in most matters than the "enemy administration." No collective political activities (e.g., rallies or demonstrations) were undertaken without at least the implicit approval of the MILF, and few individual decisions that had political implications were made without consideration of the likely reaction of the MILE Those community members summoned to MILF headquarters always endeavored to respond promptly and in person. During my

stay in Campo Muslim, a number of these summonses concerned the politically volatile issue of the conspicuous operation of a Christian charitable organization in Campo Muslim.

Child Sponsorship and Christian Hegemony in Campo Muslim

The efforts of Sister Theresa to aid victims of the 1976 earthquake first brought representatives of the Catholic diocese to Campo Muslim. Their presence continued in a more institutionalized form after her departure in 1981 (it was widely rumored that the new bishop had removed the popular Sister Theresa because he disliked her independent manner). In 1983, Reconciliation House, the community service program established by Sister Theresa, was expanded and redesignated as "the Reconciliation Center." The new bishop secured external funding for the expanded community program from the Christian Children's Fund (CCF).

By 1986, the Reconciliation Center program supported 165 students in Campo Muslim, or one child each from just less than one-fourth of the households in the community. Operating with a monthly budget of fifteen hundred dollars, the program was intended to educate children, develop community leaders, train local health workers, and provide parental education in child care, nutrition, and home economics. As articulated by its director, the program guided recipient households in value formation and social responsibility. The principal form of assistance provided to recipient families was educational support for one child per household. CCF "scholars" received the equivalent of five to ten dollars a month in tuition fees (often for Catholic schools), clothing, and school supplies. Overseas funds were generated by means of individual sponsorship arrangements. Participating children received letters from their American sponsors and were required to respond to them with the assistance of program staff members. School clothing and supplies were purchased with vouchers at the Reconciliation Center store. Parents of supported children could also receive small loans and free instruction on topics such as money management and herbal medicine.

Although this support represented more material assistance than provided by any other agency or association in Campo Muslim, the tangible results of the program as of 1986 were questionable, even perverse.[11] CCF-sponsored children did tend to be members of some of

the poorest families in the community, but after three years of participation in the program, the average monthly household income of CCF members remained well below the community average.[12] Child sponsorship arrangements had also generated new tensions and dependencies in the community.

The often ambivalent attitudes of recipients toward the CCF program were revealed most clearly to me in a conversation I had with a couple living in the very poorest interior portion of Campo Muslim. When I arrived at their house seeking census information, Andig, a laborer caring for his four-month-old son while his wife was away, invited me in. While we were talking, his wife, Taya, returned from bathing. She wrapped her wet hair in a piece of cloth, then sat and began to breast-feed her baby. As the baby nursed, Taya took a small packet of tobacco from underneath her malong (skirt), sprinkled some tobacco on a strip of newspaper, and rolled a long thin cigarette. She joined the conversation, supplementing her husband's often hesitant responses with animated comments.

She told me, "I have borne seven children but only three survive. I have my own work as a labandera [washerwoman]. I earn as much in a day as my husband." When I asked her about CCF, Taya complained about the program and brought letters and pictures from her child's sponsor to show me. I translated the letters for her and she had questions: "Is it true, as some of the ustadzes say, that children in the CCF program are sometimes sold to foreigners"? I told her I didn't think that was true. "Is it true that the Sisters change the children's names to Christian names in their letters to their sponsors"? I told her I did not know whether that happened but that many of the sponsors were not aware that the children they sponsored were Muslims, or even that they lived with their families. "What is the real reason that the sponsors' names are torn off the envelopes before their letters are given to the children?" she asked. I said that I thought it was because the CCF wanted to be able to control the correspondence between sponsors and recipient families. "You know," she said, "the sponsor of the daughter of Babu Amina visited them a few months ago. She was an old woman from America. After that woman left, Amina and her husband enlarged their house. I heard she was given one hundred dollars by the sponsor. Tell me, how can I invite the sponsor of my child to visit?" I had no answer.

Program recipients viewed themselves as clients receiving resources from mysterious and powerful outsiders. They reciprocated with the

deference, obedience, and attendance required to maintain the relationship. They complained about their powerless position vis-à-vis the program workers above them and the foreign sponsors beyond their reach, but they also defended the program against those who would remove it from the community. As it was the only source of external funding available to them, recipient families expressed a strong material interest in its continuation.

The physical as well as fiscal presence of the Catholic diocese in Campo Muslim was a political affront to the MILF and the ulama. They were unable, however, to provide comparable resources to community residents. Disapproval of the CCF program by the MILF was a cause of some considerable anxiety among its participants. Two entries from my field notes provide illustration:

Nur [my research assistant] and I went to zone four this morning to interview a man who lived there. He was not at home so we left a message with his daughter. Nur told her vaguely that we wanted to talk to him, and we made an appointment for the next morning. We then went off to another interview and returned one hour later to our house. An older woman, somewhat agitated, arrived soon after and asked for Nur. She was the wife of the first man we had intended to interview. Her daughter told her we had been asking for her husband and had described us. She recognized Nur from the description and knew that he was active in rallies connected to the "inside" (she thought I was "an Arab"). Her daughter is a CCF scholar, and she knew that there were problems concerning the "inside" and the Reconciliation Center. She thought we had come from the MILF and was worried, so came looking for Nur to see what the problem was. We explained to her the purpose of the research. I hadn't anticipated that I would be mistaken for an MILF official.[13]

[Kasan] told me that he was tired and had broken his [Ramadan] fast early today because he had made a long hard trip to Bumbaran to talk with the vice-chairman of the Kutawatu Political Office of the MILE The vice-chairman had sent him a typed letter in Magindanaon [four days earlier] asking him to come to talk about the CCF program in Campo Muslim. Kasan left very early in the morning. He went first to Parang, then took another long jeep ride east, then rode in a pedicab into the mountains to the "liberated area." At their meeting, the vice-chairman simply asked him for an "update" on the CCF program. Kasan gave him that and added his opinion that it would put great hardship on recipient families to remove the program. The vice-chairman replied that "it is best to be practical now," which Kasan took to mean that he thought that the CCF program should remain for the time being. Kasan also received an endorsement from him in the form of a signed, dated letter stating that they had met.

The most frequent services provided by the MILF involved adjudication. MILF courts heard cases on topics from homicide to land disputes to adultery. One outgrowth of the MILF's adjudication services was its registration of marriage contracts. Philippine Muslims very seldom registered births or marriages with governmental agencies. Muslim children became officially known to state authorities only when registered at public schools. Beginning in 1983 or so, the MILF provided a marriage contract form that asked for the names of the bride and groom and witnesses and the amount of the bridewealth. One copy of the contract was left with the bride and the other sent "inside" to the Kutawatu Regional Committee. Such MILF services, it may be noted, involved the direct participation of the ulama. All MILF adjudication was conducted by "inside" ulama, using Sharia (Islamic) law in a more stringent (although still locally modified) manner than it was traditionally applied. MILF marriage contract forms were provided to local ustadzes, who presided at most marriages.

The Counterelite Consolidated: The MILF-ULAMA-Professional Coalition

Crucial to the MILF recovery in Cotabato in the 1980s was an alliance of ulama and pro-MILF professionals working aboveground to advance its interests. The reason for the cooperation of the new ulama with the MILF is easy to discern. Most al-Azhar-educated ustadzes in Cotabato were, like Ustadz Ali, connected to their underground ulama colleagues by kinship links, cohort ties, and shared convictions. Although the underground ulama—who preached only at mosques in the countryside—spoke much more radically than the aboveground clerics, the latter tended to support the position of the MILF and were generally viewed as public spokesmen for the MILF.

Less obvious is the reason for the coalescence of interests between the MILF, the independent ulama, and a number of Manila-educated Cotabato professionals. While their affinity may be traced ultimately to their shared antagonisms toward the Marcos regime and its (primarily) datu collaborators in Cotabato, those shared interests were forged into a political coalition through the catalyzing efforts of a single individual. As a former political appointee of the martial law regime and the son of a datu, Zacaria Candao seemed an improbable candidate to organize an alliance of the Cotabato counterelite. At the same time, his

professional training, political experience, and kin connections furnished him with a political tool kit possessed by few other public figures in Cotabato, Muslim or Christian. Candao was a native of Cotabato City and member of a prominent city family. His father, Datu Liwa Candao, served for many years as vice-mayor of the city. Candao graduated from a Manila law school in the late 1960s, and in 1976, in the midst of the Bangsamoro Rebellion, was appointed governor of Maguindanao Province by Ferdinand Marcos on the recommendation of Simeon Datumanong, whom he replaced. Less than one year later he resigned the governorship to join the MNLF cease-fire negotiating panel in Tripoli. As he relates it, in 1977 he was asked by Nur Misuari to act as a technical advisor to the MNLF for negotiations concerning the details of the Tripoli Agreement that had been signed in December of 1976. Four months of intensive negotiations produced only stalemate, and the talks were abandoned. December of 1977 brought the split in the MNLF leadership. Candao supported the Salamat "takeover" and remained with Salamat in Cairo for one year. In 1979, Candao led a team from the Salamat faction that held exploratory talks with the Philippine government aimed at reopening formal negotiations. Those talks collapsed with the surrender of the chairman of the Kutawatu Revolutionary Committee, Amelil Malaguiok, to the government. Soon after, Candao returned to Cotabato as legal advisor to the Central Committee of the MNLF.

One of the few concrete results of the Tripoli talks was the establishment of official committees to monitor the cease-fire: one each from the government and MNLF in each region of the South. By 1978 the cease-fire arrangement had disintegrated and the original function of the committees was rendered moot. Nevertheless, Salamat decided to maintain the Cotabato cease-fire committee to document "military atrocities" in the region. Yearly reports were submitted to the Organization of the Islamic Conference. Two of the most prominent aboveground Islamic clerics in Cotabato—Ustadz Yahiya and Ustadz Pasigan, the founder of the Mahad al-Ulum al-Islamia—led the Cotabato cease-fire committee. Zacaria Candao worked closely with these men after his return and together they became the first entirely public and aboveground spokesmen for the MNLF (soon to be the MILF) in Cotabato. They also formed the core of a coalition being developed quietly but energetically by Candao.

Candao forged wider links with the Cotabato ulama by organizing and sponsoring large da'wah (call to faith) conferences. At the confer-

ence I attended in 1985, religious and regional political issues were intermingled, and copies of the official organ of the MILF Central Committee were included in every attendee's information packet. One important offshoot of the conferences was the establishment of a popular nightly da'wah radio program that provided religious and political information to listeners.

Candao also had close kinship and friendship ties with the new Muslim commercial and professional elites of Cotabato City and its environs—those who had provided so much support in the past to the Muslim rebels. He encouraged the formation of Islamic-oriented family organizations among these friends and relatives. With the help of the local ulama, he also began to build a base of support among the Muslim urban poor, particularly in Campo Muslim. A major accomplishment of the new opposition alliance organized by Zacaria Candao was the introduction of a new potent political vocabulary into Muslim politics in Cotabato. "Islamic Unity" became a catchphrase for the local opposition, and, for the first time, Islamic phraseology began to be used in everyday political discourse in Muslim Cotabato. The aboveground coalition combined an Islamic message with well-developed kinship and economic ties among two rising elite groups—the ulama and the professionals and entrepreneurs, who were, in many cases, the sons of successful smugglers. Joined with the underground MILF, the alliance presented a new and formidable challenge to the collaborative traditionalism of the datus who monopolized formal political posts in Muslim Cotabato in the early 1980s.

An extraordinary event that occurred in conjunction with the 1985 "Da'wah Conference" illustrates the Muslim opposition's unprecedented use of Islamic renewal as a cultural frame for public political protest against the martial law regime and the datu establishment. The organizers of the conference staged a large parade through the city to celebrate its opening. As many as ten thousand madrasah students from throughout the province marched from the Mahad in Campo Muslim, through the city plaza to the parade ground of the Central Elementary School, where they were reviewed by a number of dignitaries including the Muslim military commander of the region and the Muslim governor of the province.

As the very first event of its kind in Cotabato, the parade was remarkable in itself, displaying the exceptional growth in Islamic education in the province in the previous five years. However, it also included a political demonstration by Muslim college students that had

been planned weeks earlier at the Mahad in Campo Muslim. At that meeting, representatives from various Muslim student organizations at local colleges were addressed by Ustadz Ali, who spoke about the courage required to demonstrate publicly and told stories of his days as a student in Cairo demonstrating against Nasser. The students gathered again at the Mahad on the day before the parade to prepare placards and banners. Some of those carried messages (in English), such as "Allah Hates Oppressors" and "We support the Mujahideen in Afghanistan," and a few had quotations in Arabic from the Qur'an. Others held slogans that pointedly though obliquely protested the martial law regime ("Muslims and Christians Have a Common Enemy"), while still others voiced explicit criticism ("Military Out of Mindanao"). The most directly confrontational slogan stated: "MMA = Ministry of Munafiq Affairs." This message denounced the Ministry of Muslim Affairs, a new government agency created as part of the Marcos regime's unilateral implementation of the Tripoli Agreement, as a hypocritical, anti-Islamic (munafiq) institution. Zacaria Candao arrived at the Mahad later in the day and reviewed the banners. He asked that the four most controversial not be carried in the parade but approved their display at the school ground afterward. While it is not clear that Zacaria Candao or Ustadz Ali actually initiated the student demonstration, they clearly approved and facilitated it. With the addition of the student demonstrators, the parade represented not only the largest Islamic event ever held in the province but also the very first mass political action engaged in by Cotabato Muslims.[14]

Traditional Elites and the Post-Rebellion Establishment

By 1980, with the end of the active rebellion and the relaxation of stringent military rule, the datus of Cotabato had reestablished themselves to a remarkable degree in positions of political power. Members of datu families long allied with President Marcos held positions as minister of Muslim Affairs (a recently created cabinet-level post), representative to the Batasang Pambansa (or National Congress, created in 1978 by presidential decree), and governor of the province. Members of datu families more recently affiliated with the Marcos regime (i.e., since the declaration of martial law) held positions as provincial board member, regional assemblyman, and chairman of the Philippine

Amanah Bank (a government development bank operated on Islamic guidelines), and as vice-mayor and city council member of Cotabato City. Additionally, rebel returnees who were members of datu families held prominent positions in the regional autonomous government. In all, six of eight regional assemblymen from Maguindanao Province were members of prominent datu families,[15] and six of the seven officers of the provincial committee of the ruling party, the KBL (Kilusang Bagong Lipunan, or New Society Movement), were traditional elites. Of seventeen municipalities in Maguindanao Province, twelve were headed by datus. On the whole, traditional elites appeared to have survived martial law and the Bangsamoro Rebellion with little permanent damage to their political capabilities. With effective one-party rule and an increase in development funds channeled from the central government to Cotabato, the political positions of many collaborating datus were, in fact, more secure and potentially more profitable than before martial law.

Datu Ali Dimaporo, the Maranao governor of the neighboring province of Lanao Del Sur, anchored the government-datu alliance throughout Muslim Mindanao. Dimaporo's ties with President Marcos had made him both enormously wealthy (his holdings reportedly included apartment buildings in Los Angeles) and a national political figure. He ruled his province as a traditional domain and maintained a sizable private army. By the early 1980s, Ali Dimaporo was widely acknowledged to be the most powerful politician in Mindanao. He not only had a direct line to the presidential palace (he was, it was said, the only Muslim whom President Marcos really trusted) but maintained a warm relationship with the Philippine military. He flew on military airplanes, gave his blessings to military operations against Muslim rebels, and reportedly engaged in mutually beneficial business deals with high military officers. He was the leader of the KBL in Mindanao and the sole gatekeeper between the Marcos regime and Mindanao Muslims. All successful petitions by Muslims to the Marcos administration were said to pass through him.

In August 1982, Ferdinand Marcos appointed Dimaporo as the only Muslim member of the National Executive Committee—a body that served in a special advisory role to the president (McAmis 1983). Later in the year Dimaporo—whose genealogical claims to nobility were equivocal at best—arranged to have his preeminent political role in Mindanao traditionally validated. He had himself "enthroned" as "His Royal Highness, the Sultan of Masiu" (in some accounts, as the

Sultan of all the Sultans) in a lavish ceremony attended by President and Mrs. Marcos and much of the traditional nobility of Muslim Mindanao (McAmis 1983).[16] The self-proclamation of All Dimaporo is credited with encouraging a series of similar proclamations in Cotabato. Old titles were resurrected and new "royal descendants" organizations sprang up at a rapid rate between 1982 and 1986.

The collaborating datus of Cotabato and the administration they served provided few, if any, discernible services to ordinary Muslims between 1980 and 1986. The Regional Autonomous Government had no power of taxation and little government money to spend. Most of what budget it had was spent on itself. The expansive RAG complex at the edge of the city included, among other things, a bowling alley and tennis courts for the use of representatives and employees. Because the RAG had no real power or funds to implement projects, it was viewed by many as simply an "unnecessary, expensive bottleneck to getting projects approved and implemented" (McAmis 1983, 37). The agency established by the martial law administration to manage economic development in the Muslim South—the Southern Philippines Development Authority—was, by 1980, officially headed by Imelda Marcos. Its only recognizable accomplishment in Cotabato City was a large housing development located just south of the city, not far from the RAG complex. The prices of homes built there were far beyond the economic capabilities of low-income families. Virtually all were owned by middle-income government employees.

Government assistance to residents of Campo Muslim was scarce and irregular. A number of government projects had been promised over the years in the community, and some had even been initiated, but none was ever fully implemented. The only governmental material assistance I witnessed in Campo Muslim occurred during the 1986 presidential election campaign when a KBL campaign van arrived in Campo Muslim to distribute free medicine. A large crowd of residents gathered and signed their names on KBL lists in order to receive medicines marked prominently with labels that read: "For government use, not for sale." I heard stories of other assistance provided during election campaigns by certain local officeholders seeking reelection who installed streetlights or water pumps in the community. The only regular service provided by Datu Kamsa, the barangay captain, was adjudication. During the time I lived in Campo Muslim, Datu Kamsa began to charge money for his adjudication services, ostensibly to discourage frivolous claims.

The opposed political coalitions I have just described did not constitute neatly delineated camps. They were, for one, thoroughly crosscut by kin connections. The complex political attachments among Zacaria Candao—the leader of the opposition alliance—and his datu relatives (some of whom live in or near Campo Muslim) provide illustration. Candao and Datu Kamsa—the barangay captain of Campo Muslim and a Marcos loyalist—were second cousins. Datu Kamsa was opposed in the 1980 election for barangay captain by Datu Mokamad, his first cousin who was also the first cousin and close ally of Zacaria Candao. The election was fiercely contested, with community observers remarking that had the two candidates not been so closely related there would surely have been bloodshed. The brother of Datu Mokamad, Datu Simeon, had joined the KBL and occupied a high provincial office. Another brother, Datu Monib, fought with the rebels and still actively supported the MILE As a direct descendent of the Umarmaya sa Magindanao, one of the highest officeholders of the Magindanao Sultanate, Zacaria Candao possessed a closer descent relationship to the Magindanao core nobility than any of his datu cousins, yet he had chosen not to call himself "datu."

Such tangled relationships demonstrate that political loyalties did not divide cleanly along family lines, with the result that close relatives were sometimes aligned with bitterly opposed political factions. While I found no direct evidence that such alignments were the outcome of family-based strategies to spread political risk, the presence of close relatives among one's political antagonists did undoubtedly facilitate not only interfactional communication but also personal political realignment under changed conditions. The one clearly discernible kinbased political pattern in post-rebellion Cotabato was found among members of the most powerful and well-established datu families in the province, who tended overwhelmingly to align with the government-datu coalition.

The Struggle for Moral Authority in Cotabato

With the political arena so narrowly circumscribed by the authoritarian state regime in the early 1980s, the counterelite alliance confronted the datu establishment in cultural arenas, disputing their right to exercise moral authority over Cotabato's Muslims. The challenge to traditional moral authority was extended incrementally by the newly active

ulama in the form of recommended alterations to accepted local practices. Recognizing that the proposed reforms were an attempt to undermine the core of the myth of sanctified inequality—the axiom that as direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad moral authority was constituted only in them—datus countered with an intensified traditionalism. While this ideological struggle was waged over the right to command the faithful, voices from Campo Muslim reveal that Muslim subordinates often held independent opinions and acted upon them.

In Campo Muslim, contestations occurred in three cultural arenas: religious ritual, popular culture, and adjudication; disputes in the first two arenas concerned ritual and celebratory activities surrounding two very important life crises: weddings and funerals. In Campo Muslim in 1985, I found that certain core Islamic practices—fasting during the month of Ramadan, strict abstention from pork, ritual circumcision of males, and the virtual absence of apostasy—had existed prior to the emergence of the ustadzes and were little affected by them. Other areas of religious practice and personal behavior had undergone appreciable change that community members agreed was entirely positive. In the estimation of residents, the attendance of male community members at Friday congregational worship had increased and a greater number of individuals were attentive to daily prayers. Incidents of public drinking and gambling by community residents had apparently declined. Certain other beliefs and practices—particularly those concerning spirits and magic—had yet to be addressed by religious reformers.

But some aspects of the cultural life of Campo Muslim were strongly (though not always loudly) contested. These were cherished (and usually well-established) practices that the ulama wanted to modify or eliminate. One contested area concerned traditional mortuary rituals. As with other Islamic peoples in Southeast Asia (see, e.g., Bowen 1993), Muslims in Cotabato have added local accretions—involving additional prayers, the use of incense, and ritual ablutions at the grave site—to the conventional Islamic burial service. The ustadzes strongly disapproved of these practices as adulterations. More highly contested were the extended death commemoration rituals—the most important funerary ceremonies in the community. In common with a number of other Southeast Asian societies—both Islamic and non-Islamic—traditional belief requires propitiation ceremonies for the deceased at intervals of 3, 7, 40, 100, and 365 days after death. In Cotabato, these ceremonies take the form of ritual meals (kanduli ) at which prayers (duwa; in Arabic, du'a ) are recited for the deceased.[17] In the

most traditional form of the kanduli, ritual specialists (panditas ) chant the prayers in a version of the Sufi tahlil , or prayer litany (Reid 1984), in which the first words of the confession of faith, "La ilaha ilia Allah" (There is no god but God), are recited repeatedly at various tempos accompanied by the swaying of the body from side to side. The rhythmic voices and movement produce a peaceful, entrancing effect in participants and listeners.

After initially objecting to all such propitiation ceremonies for the deceased, the ustadzes later modified their position and condoned the third day (telu a gay ) death commemoration ceremony. They have nonetheless strongly criticized further ceremonies as ritually improper and wasteful of resources and disapprove of the traditional Sufic content of the kanduli. The economic argument of the ulama, that extended death commemorations were unduly expensive, pertained to customary ritual practice prior to 1972. Ritual feasts before that time involved very substantial costs for the relatives of the deceased, and it was not unusual for individuals to incur major debts as a consequence of sponsoring such feasts. Since 1972 the expenses associated with death commemorations had been substantially reduced (without a concomitant reduction in the number of commemorations) as the result of moderations in the scale of ceremonies necessitated by the calamitous economic losses of that period.

The ustadzes' strong disapproval of extended death rituals distressed many ordinary Muslims, who worried about losing the means to ensure that the spirits of their dead relatives were at peace. One community elder expressed the general uneasiness of many residents at the pronouncements of the ustadzes: "First they said that traditional [religious] practices would remain. Then they announced that they would all be removed, then that only some would be kept. People are confused." Trading on this unease, traditional elites took the lead in defending traditional practices as integral aspects of Magindanaon culture and accused the ulama of extremism in their efforts at religious reform. The comments of Datu Adil are representative of their assertions:

Our elders had a saying: "Amayngka madakel niya a ulama nakauma, a magkapir tanu [When many clerics come among us we will become unbelievers]." Before [the emergence of the ulama], I didn't know what this meant, but now I do. It means that the ulama cause trouble. If one hundred clerics return to the Philippines [from studying in the Middle East], one hundred different translations of Islam will develop.[18]

The ulama are trying to destroy our culture. They are influenced by Saudi Arabia, and the Saudi government is controlled by Wahhabis.[19] Wahhabis are not Sunnis [the major sect of Islam, to which belong virtually all the Muslims of Southeast Asia] . . . According to the ustadzes, the death commemoration is not allowed, but it is a beautiful practice . . . What has happened now is that, on the seventh day after a death, people report that they hear the voice of the deceased crying; "I am hungry, give me food." I have been told about one case where the ghost of the deceased appeared, and ran after an ustadz.

Despite the misgivings of ordinary Muslims and the active resistance of datus, the number of extended death rituals beyond seven days after a death seems to be declining. Of the ten or twelve death rituals I attended or was told about during my stay in Cotabato City, only two occurred later than seven days following a death—one at one hundred days and the other at one year. Both were held by datu families, and both included traditional tahlil chanting, which is also becoming less common. At most of the kandulis I attended, traditional chanting did not occur. In general, only relatively wealthy datu families—those most anxious to counter the influence of the ustadzes and best able to afford the expense—continued to hold the full range of traditional death celebrations. It is an ironic development, though not a surprising one in light of the history of Cotabato datus in the modern period, that those who have most energetically defended traditional religious ceremonies have also been the most thoroughly Westernized.

Implicit in the assertions of traditional elites about the religious reforms of the clerics is that they deprive local Muslims not only of cherished cultural meanings but of occasions for celebration. That implication seems justified when the range of attempted reforms is examined. The traditional celebrations (common throughout Muslim Southeast Asia) associated with two holy days—Maulid en Nabi (the birthday of the Prophet—Arabic Maulidu'n-Nabi) and the Layatul Kadir (the Night of Power—Arabic Lailatu'l-Qadr) have been de-emphasized or simplified due to the influence of the ustadzes. They have also discouraged elaborate celebrations for those returning from the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj). Additionally, clerics strongly disapproved of at least three indigenous cultural activities that were particularly enjoyed by young people. One concerns the death vigil traditionally kept by family, friends, and neighbors for seven nights after the death of a community member. Although the body (in accord with standard Islamic practice) is normally buried within twenty-four hours, it is be-

lieved that the spirit of the deceased remains at the family house for seven days and requires company. The vigil was an important social occasion for adolescent girls and boys, who stayed awake the entire night playing cards, mah-jongg, and other group games, occasionally even gambling for money stakes. A passage from my field notes describes one such vigil: "Tonight I attended a vigil for Kasan's mother. About twenty young people, most of them boys, played cards for pieces of candy. Two separate card games were in progress and the noise level was quite high. Kasan's brother-in-law had to hush them twice because of the Qur'an reading going on in the back room. There three imams read separate sections of the Qur'an simultaneously. The goal is to have the Qur'an recited completely once, and ideally twice, during the seven-day vigil."

The second activity, known as panguyaw , occurred on a wedding night. It was a postwedding parlor game in which the groom playfully pursued the bride around a sitting room to the noisy encouragement of the unmarried female friends of the bride. On the occasion I witnessed, the unmarried friends of the bride and groom gathered after the wedding ceremony at the house where the bridal chamber was located. As photographs were being taken, the young female friends of the bride encouraged the groom to show affection to his new wife by putting his arm around her, holding her hand, or kissing her on the cheek. The young spectators would shriek with glee when he complied with their requests. These popular practices have by no means been eliminated by the objections of the ustadzes, but clerical disapproval has clearly decreased their incidence and social intensity.

The third offending activity was an innovative form of indigenous popular entertainment first developed during the rebellion. The dayunday ("song duel") is an exceedingly popular form of public entertainment most often found in association with wedding celebrations. It is a modern adaptation of a traditional song form using Western instruments (guitar) and some aspects of Western showmanship, yet is still unmistakably an indigenous non-Western entertainment.[20] The dayunday involves a song contest between a man and a woman, or more commonly a three-way competition between two women and one man (or vice versa), with the singers trading off extemporaneous verses of romantic repartee. Dayunday singers are professional entertainers hired most commonly to perform at wedding celebrations. Ordinary Muslims would walk miles to attend dayunday performances that typically continued throughout the night.

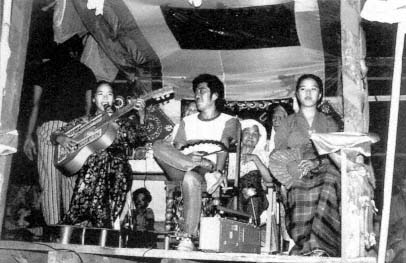

9.

A wedding procession near Campo Muslim. The bride,

with head bowed as prescribed by custom, is accompanied

by female attendants holding decorated umbrellas.

The ustadzes were offended by the dayunday and campaigned without success to ban it. They objected to men and women performing together and singing openly about love and romance. They claimed that dayunday performances encouraged unlawful sexual relations and elopements. Dayunday lyrics express sexual attraction indirectly, employing deep metaphors and archaic language.[21] Stage gestures—winks, nods, and nudges—depict flirtatiousness without being sexually suggestive. The overt sexual content found in the Western movies and music so pervasive in Cotabato City is entirely absent in dayunday performances. The ustadzes nevertheless attacked the dayunday more frequently and vehemently than they objected to Western entertainments because they viewed the dayunday as a pernicious cultural departure. It represented a revitalization (and, to some extent, a Westernization) of traditional popular culture at a time when the ulama were attempting to refashion social behavior to conform with the tenets of Islam. As an indigenous development it was more troubling than fully external influences because it represented a cultural drift directly away from the politico-religious project of the ulama. When it became clear that their denunciations had done nothing to lessen the popularity of

10.

A 1988 dayunday performance in Campo Muslim. This public performance,

given by three professional dayunday singers in conjunction with a wedding celebration,

lasted from dusk till dawn and was attended by hundreds of community residents.

the dayunday, many ustadzes simply refused to attend weddings where the dayunday was performed. As clerics condemned dayundays, datus embraced them. Traditional elites sponsored every one of the dayundays I attended and, with the resumption of electoral politics in 1985, they became the most popular way to ensure large crowds at political rallies.

Another major area of cultural contention between clerics and traditional elites was adjudication. Datus pointed to instances of the austere application of Islamic law by certain clerics as evidence for ulama judicial extremism, as opposed to the more flexible penalties associated with traditional Magindanaon jurisprudence, where religious and social transgressions were "cured" by fines. During the latter part of the rebellion and in the years following the cease-fire, corpses (most often of females) would regularly be found floating down the Pulangi River from areas under rebel control. During my stay in Cotabato City fishermen still occasionally retrieved corpses from the river. It was widely accepted that these were the bodies of individuals punished for unlawful sexual relations by particularly strict ustadzes operating with the rebel forces. Many Muslims were troubled by this evidence of severe

compliance with the dictates of Sharia law, because it represented a serious escalation from the fines and forced marriages or beatings traditionally imposed for such transgressions. A story told by Datu Adil about one of his acts of adjudication illustrates the differences between traditional customs and the presumed adjudication practices of the MILF:

A man who was married with four children eloped with a woman to Davao. A party with guns was sent after him. The couple came to me in the middle of the night and asked me to help them. The man said: "I am a traveling insurance salesman, and while I was traveling I met this young woman and fell in love and we eloped." She was related to the Nuling datus, and ten years younger than the man. Her father was my friend. That was why they came to me.

When the parents of the woman heard of my involvement they asked that the distribution of the bantingan [bridewealth] be held at my house and the wedding at their place. The bridewealth was seven hundred pesos. I fined the man three hundred pesos. I could have taken the whole fine for myself but I distributed most of it. They were in trouble when they came to me. The girl's parents had contacted Hadji Murad and the MILF was looking for them. The man would probably have been killed.

Despite stories such as these, and the clear evidence of a certain number of incidents of harsh punishments meted out by members of the "inside" ulama, the majority of MILF adjudicators reportedly did not dispense legal decisions resulting in penalties that were significantly different from those traditionally imposed. The reason most often given for their leniency was that local Muslims were not yet genuine Muslims and so did not deserve strict Islamic sanctions.

Popular Opinions and Pragmatic Responses

Ordinary urban Muslims were not passive recipients of the cultural assertions of competing elite groups. On the contrary, they had distinct views of their own and responded with a good deal of pragmatic resistance to the moral imperatives of the ulama or the traditional appeals of the datus.

Scrutinizing the Independent Ulama

As I walked with Nur Miskin one day along the busy river road connecting Campo Muslim with the rest of the city, we happened to pass a prominent ustadz walking toward the community. The sight of the us-

tadz unaccompanied and on foot prompted Nur to remark, "See there, he is not like the datus, who travel only in cars and with bodyguards."

The residents of Campo Muslim found much that was appealing about the new ulama. As with Nur, they often expressed their approval to me in the form of a negative comparison: ustadzes are unlike datus. Residents also respected the ustadzes for the Islamic learning they had acquired, and they appreciated the social messages contained in some of the Friday sermons at the Mahad mosque.[22] Their admiration for the ulama notwithstanding, community members were, on the whole, quite resistant to ulama attempts to purify ritual practice or restrict popular celebration. The various proposed reforms caused confusion and apprehension as individuals were torn between abandoning identity-affirming rituals and practices and engaging in what the ustadzes had characterized as un-Islamic behavior.

The mediator in many of these cultural disputes in the community was Imam Akmad, the head imam of the Campo Muslim mosque. The imam maintained close relationships with local ustadzes and had been much influenced by their teachings. At the same time, he identified with community members who were confused by the changes promoted by the ustadzes. In counseling community members, Imam Akmad distinguished between behavior that is un-Islamic and that which is anti-Islamic, and he suggested that there was nothing anti-Islamic in traditional rituals. He also expressed the sentiments of many community members by drawing a distinction between Islamization and Arabization. He advised members of his congregation that they were obliged to follow the injunctions of the Qur'an but not the practices of the people of the Middle East, and that the ustadzes sometimes confused these two. I once heard him comment that Allah revealed himself to the Arabs precisely because their behavior was so wicked. On balance, the imam sincerely respected the ustadzes and counseled others to listen to their teachings. Yet he did not urge community members to change traditional practices, noting that the ustadzes were still young and lacking in practical knowledge. He himself had not ceased performing the "emergency" marriages traditionally required for unmarried women who had become pregnant. The ulama had disallowed these, declaring that what is haram (forbidden) cannot be made halal (permissible) by means of post-hoc authorization.[23] Imam Akmad was sympathetic to the principle guiding the ustadzes' pronouncement but was also well aware that strict compliance with their prohibition would be impractical—even injurious—insofar as emergency

marriages were most often arranged to avert violent retribution for the grave offense to the honor of the family of a pregnant but unmarried girl. The imam, a man possessed of considerable spiritual potency, had made his own compromise with the new ritual order by choosing not to exercise his supernatural powers lest doing so be construed as a form of the sin of shirk , or attempted partnership with the divinity.[24]

The one-quarter of community households with children who were CCF recipients also quietly but firmly resisted two attempts by the local ulama to force the removal of the program from the community. Community ustadzes were understandably threatened by a large and well-funded program that promoted (intentionally or not) Christian cultural hegemony in a Muslim community. Community recipients held some similar feelings but recognized as well that most of the ustadzes neither shared their poverty nor seemed concerned to alleviate it. Although many of the parents of CCF recipient children were acutely anxious at being associated with activities that had been characterized as anti-Islamic by the community ulama and the MILF, they nevertheless made known to the ustadzes that they would not cooperate in the program's removal unless another could be provided in its place.[25]

As teachers rather than ritual specialists, the ustadzes did not play an especially active role in the daily religious life of the community. The effect of their disapproval of so many activities associated with marriage and funeral ceremonies was to diminish their participation at ritual events they might otherwise have attended. Consequently, although the ustadzes were acknowledged as the most prominent religious figures in the community, they were not viewed by residents as specifically "community" leaders, nor indeed were they regarded as integral to community life. That fact was dramatically illustrated at the single most important community religious service of the year—the assembly prayers to celebrate Idul Fitr, the holy day marking the end of the Ramadan fast. The service was conducted in the community mosque rather than the Friday mosque at the Mahad and without the participation of a single ustadz.

Although I did not directly solicit community sentiments about the MILF, a number of community residents volunteered their opinions. From them I received the impression that there was a great deal of community support for the leaders of the Cotabato MILF forces who, despite their popularity, remained somewhat shadowy figures. I also sensed concern among community members to avoid offending (intentionally or unintentionally) representatives of a powerful armed under-

ground organization. The only open (though quietly expressed) resentment I heard regarding MILF policies concerned the appropriation of community pitra (Arabic: fitrah , zakat al-fitr ) contributions by the local MILF. Pitra payments, made at the end of the Ramadan fast, consisted in Cotabato of a quantity of polished rice equal to about two quarts (or its cash equivalent) per person in a household. One interpretation of the Islamic notion of zakat (almsgiving), of which pitra payments are a part, is that the giving of alms is obligatory and those alms should flow directly to mujahideen (those who struggle in defense of Islam) in periods of active conflict with nonbelievers.[26] On that basis, MILF representatives had, each year since the beginning of the Bangsamoro Rebellion, claimed the largest portion of the pitra payments collected by local imams, who were required by the MILF to keep a list of contributing households. Some Campo Muslim residents commented that the continued appropriation was unfair because many of the people in the community had greater economic needs than the rebels, who grew food for themselves in their rural camps. They also disputed the MILF-ulama interpretation of the contemporary situation, noting that the faithful were only obliged to support the mujahideen when they were actively fighting, and the war in Cotabato had been inactive for some time.[27]

Disregarding Traditional Authority

Despite their hesitancy about the reform program of the ulama, ordinary Muslims were not enthusiastic about the various appeals to shared tradition made by the datu elite. As mentioned above, I found little community regard for the traditional nobility, and some vocal disregard. Younger community residents, in particular, gave little heed to what they often referred to as "datu business." Some young people openly mocked the flowery speech of the elderly Sultan sa Magindanao when he occasionally gave speeches on the radio. Others hastened to point out to me that the paired words "da "and "tu "(meaning "absence" and "to grow") amounted to "no growth." Even community elders expressed their dislike of behavior they referred to as datu-datu —the social posing and status competition associated with traditional elites.

Opinions gathered from structured interviews provide a revealing pattern of attitudes concerning traditional elites. When asked to name the most powerful datu they knew of, 36 percent of community respondents could cite no one. Another 24 percent cited Zacaria

Candao, who at the time of the interviews had just been appointed governor of the province by the newly elected Corazon Aquino. Candao, as I have noted, neither referred to himself as a datu nor identified himself with the traditional nobility. Eighteen percent of respondents cited Datu Kamsa, the barangay captain. These responses indicate that a significant number of community residents no longer associated datus with political power (about 10 percent of respondents cited datus, such as Datu Udtug, who were no longer living), and that many of those who did continued to understand the term "datu" pragmatically, as one who rules.[28]

While a majority of Campo Muslim respondents (59.8 percent) reported that they would seek adjudication from Datu Kamsa, the barangay captain, in the event of a dispute with their neighbors, I also found that individuals brought different varieties of minor disputes to a range of adjudicators that included Imam Akmad, Kasan Kamid (in his capacity as formal leader of an organization of Campo Muslim neighbors), and other influential community members. For more consequential legal cases, residents relied on various forums, including both the Philippine legal system and the MILF courts. It was not, in fact, unusual for an individual to present a single claim successively in more than one forum in an attempt to receive a single favorable ruling. One community resident (an unusually litigious individual) became involved in a land conflict and first argued his case in the local provincial court where he received an unfavorable ruling. He then brought his claim "inside" to the MILF courts, where the decision again went against him. Subsequently, he presented his case before the government Sharia Court, a body of the regional autonomous government that applied a special law code loosely based on Sharia law. The Sharia Court had been labeled a "fake Islamic court" by the MILF and, at the time this case was brought before it, was very little used by Cotabato Muslims (the government Sharia Court also denied the man's claim).