Chapter 5

America's Moros

In his 1983 work on early American colonial rule in the Muslim Philippines, Peter Gowing cites a passage from a 1909 report to General Tasker Bliss, the second governor of the "Moro Province": "I find that the Moros who attended the St. Louis Exposition bought and brought in, apparently without question, no less than fifty rifles and revolvers of the very latest models . . . [M]any of them have changed hands, thus making it a very profitable business for the Moros who were lucky enough to have visited the United States" (Lt. Jesse Gaston to Bliss, January 8, 1909, cited in Gowing 1983, 177). While not remarked upon by Gowing, this short passage says much about the responses of Philippine Muslims to the early American occupation of the southern Philippines. It refers to the one hundred "Moros" (certainly many datus among them) who, with representatives of other subject groups of the American-held Philippines (one thousand individuals in all), were brought to the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair and placed on exhibit. The report complains of the behavior of the Moros, who apparently did not content themselves with their assigned roles in a "living ethnological display" but also spent their time shopping for the most sophisticated firearms that American industry had to offer (Rydell 1984, 162). It is tempting to imagine them making their way from their "ethnological village" in the "Philippine Reservation" to the Palace of Manufactures, there to regard those gleaming, high-calibered benefits of Western technological progress (1984, 167).

This depiction of subjugated Philippine Muslims as both objects of colonial intentions (quite literally so in this instance) and strategizing subjects is characteristic of political relations in Cotabato throughout the American period, especially those between Muslim notables and colonial agents. The most successful Cotabato datus of the colonial period publicly collaborated with American colonial authorities and used American resources to consolidate both their economic bases and their political control over the Muslim populace. This chapter examines Cotabato datus as both colonial subjects and local rulers—as points of articulation between two conjoined fields of force. It depicts the complex power relations of colonial Cotabato and the construction during the colonial period of a transcendent Philippine Muslim identity.

The story of the incorporation of the Cotabato sultanates into the Philippine colonial state has been told from the perspective of the colonizers as part of broader studies of American colonial policy toward Philippine Muslims, by Peter Gowing (1983) and Benjamin Thomas (1971). It has been related in a more specific, ethnohistorical form by Reynaldo Ileto (1971) and Jeremy Beckett (1982). I have chosen to tell the story primarily by means of political biographies of four twentieth-century datus. I do so to avoid retreading previously explored historical terrain and for more substantive reasons as well.

First, in Cotabato, more than in any other Muslim province, colonial pacification and assimilation were expedited by the strategic actions of particular datus, with the result that there was less concerted armed resistance to American colonialism there than anywhere else in the Philippine South. Second, despite the context of profound socioeconomic changes—including the formal abolition of slavery and the introduction of private property in land—the basic character of political relations between Magindanaon datus and subordinates changed hardly at all between 1890 and 1968. Accordingly, even those datus most closely associated with the colonial regime were able to maintain traditionally based followings and exercise control over followers in much the same way as they had in precolonial times. Magindanaon datus—in sharp contrast to the collaborating traditional elites (uleebelang ) of the same period in Aceh (Siegel 1969) but similar to contemporary Christian Filipino elites (Beckett 1982)—were not socially isolated by their connections to alien authority and remained soundly at the center of regional politics during the colonial period. An examination of the careers of selected twentieth century datus thus offers a fruitful approach for comprehending the political dynamics of the period.

Third, as we shall see, American colonial authorities, especially in the first years of their occupation, ruled indirectly through cooperating datus, concerning themselves little with the Muslim populace but rather intensely with those who claimed to be their leaders. In the case of colonial Cotabato in particular, reports concerning local elites comprise the great majority of primary source materials in colonial archives.[1]

Fourth and most significant, the investigation of the political careers of selected Cotabato datus during the colonial period provides additional insight into the twin myths of Philippine Muslim nationalism introduced in the foregoing chapters. These colonial lives chronicle, on the one hand, the remarkable persistence of precolonial relations of domination—including the justificatory myth of sanctified inequality—despite the virtual dissolution of the core nobility and the formal transformation of local political structures. On the other hand, they reveal the gradual development, with the active encouragement of colonial agents, of a new transcendent ethnoreligious identity as "Moros."[2]

Cotabato Under Spanish and American Rule: The Emergence of a Collaborationist Elite

Effective Spanish political control of the Cotabato Basin was shortlived and lightly felt. Although the Spaniards occupied the delta in 1861, it was not until 1888 that they were able, with the help of some early datu collaborators, to splinter the powerful alliance constructed by Datu Utu, the de facto Sultan of Buayan, and pressure him into retirement in 1890, thus finally attaining military supremacy of the entire region (Ileto 1971). Spanish colonial control consisted almost exclusively of the establishment and maintenance of military garrisons, with little attempt made to administer the native population. By 1899, the Spaniards were withdrawing from Cotabato, leaving it, after a brief independent interlude, to a new colonial power.

Early rule by Americans in the Muslim Philippines followed a pattern quite similar to their governance of the rest of the colony—pious paternalism punctuated by often brutal pacification operations. In the Muslim South, however, pacification took longer to achieve, requiring even harsher methods, while paternalism was also more pronounced. Military government gave way to civil rule in the Visayas and Luzon in 1901, but continued in Muslim areas until 1913. In 1906 in Sulu, more than six hundred men, women, and children were killed by

American forces in the battle of Bud Dajo, prompting American journalists to decry the carnage (Gowing 1983, 164).[3] Gowing observes that the slaughter at Bud Dajo—the consequence of a local rebellion against the imposition of a head tax—"was simply the last, most dramatic and most publicized of a long list of military operations" authorized by General Leonard Wood, the first military governor of the Muslim Philippines (1983, 164). In all, at least three thousand Philippine Muslims were killed by American forces between 1903 and 1906 (Gowing 1983, 164).[4] Violent repression was supplemented by an administrative paternalism grounded in the colonial perception that, as non-Christians, Muslim Filipinos were among the most benighted members of a backward people and required additional tutelage and protection to bring about "their advancement into civilization and material prosperity" (Philippine Commission Act No 253, Oct. 2, 1901, quoted in Thomas 1971, 9).

That Mindanao did not became an American planter colony, despite the wishes of a considerable number of colonial administrators and businessmen (and notwithstanding its demonstrated suitability for rubber cultivation—see Pelzer 1945, 105), is attributable to the same complex of causes that saw America's Philippine colony persist for more than forty-five years while purportedly on the verge of decolonization virtually since its inception. The peculiar policy that undergirded American colonial rule in the Philippines is termed by David Steinberg "self-liquidating imperialism" (1987, 276). That policy was originally shaped and periodically reconfigured as the result of contention between two domestic political blocs divided along party and sectoral lines. Arrayed around the Republican Party were interest groups in favor of American imperialist expansion: industrialists searching for markets and cheap sources of raw materials, and military analysts mindful of the strategic advantages of Far Eastern naval bases. Aligned against them were interests associated with the Democratic Party: a powerful lobby consisting principally of domestic beet-and cane-sugar producers (but also tobacco, hemp, and fruit growers, fearing competition from foreign crops), and the considerable political influence of the Anti-Imperialist League, headquartered in Boston (Pelzer 1945; Wernstedt and Simkins 1965; Constantino 1975; May 1987; Walton 1984).

With its dual doctrines of "free trade (especially sugar for manufacturers) and scheduled decolonization (at least in its formal trappings)," American colonial policy reflected a compromise between

those opposed domestic interests (Walton 1984, 49). The anticolonial political bloc strongly opposed the large-scale entry of plantation capital into the Philippines and succeeded in limiting the maximum amount of public land that could legally be acquired to 16 hectares per individual and 1,024 hectares for corporations and associations. Philippine nationalist politicians (with the help of a reluctant American Congress) resisted all later attempts (including strong lobbying by American administrators of Muslim areas) to relax limits on the size of private landholdings (Pelzer 1945; Thomas 1971). Those limits effectively foreclosed the development of plantation agriculture on any significant scale in Mindanao until the end of the American period. Instead, Mindanao was developed as a settler colony. The homestead system instituted under the Americans had little impact on Muslim areas during the colonial period, but its successor programs under the Philippine Commonwealth and Republic were to have profound consequences for the indigenous inhabitants of the Cotabato Basin.

Colonial Policy and the Cotabato Triumvirate

The course of colonial policy in the region that the Americans termed "Moroland" (Gowing 1983) was altered abruptly more than once as American aims in the rest of the archipelago (and Philippine nationalist opposition to those aims) evolved. The earliest American governance in the Muslim South was an indirect rule similar to that found at the time in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. It was a strategy intended to neutralize Muslim groups in the South in order to concentrate on overpowering Philippine independence forces in the North. In 1899, a formal treaty, the Bates Agreement, was signed with the Sultan of Sulu in which the Americans promised not to interfere in Sulu religion, law, and commerce (and to pay the sultan and his datus monthly stipends) in exchange for the sultan's acknowledgment of United States sovereignty. Informal agreements of a similar nature were made during that period with Muslim leaders in the rest of the Muslim South, including Cotabato (Gowing 1983).

The colonial policy of indirect rule was soon modified and not long thereafter abandoned. In 1903, a tribal ward system was established in the newly constituted Moro Province wherein local headmen were placed under the direct supervision of a district governor (Gowing 1983). The rationale for the administrative shift toward direct rule was given by General Leonard Wood, the first governor of the Moro

Province, in a 1904 letter to an English friend: "You are quite content to maintain rajahs and sultans and other species of royalty, but we, with our plain ideas of doing things, find these gentlemen outside of our scheme of government, and so have to start at this kind of proposition a little differently. Our policy is to develop individualism among these people and, little by little, to teach them to stand on their own two feet independent of petty chieftains. In order to do this the chief or headman has to be given some position of more or less authority under the government, but he ceases to have any divine rights" (Wood quoted in Gowing 1983, 115).[5] The Bates Agreement was unilaterally abrogated by the United States in 1905 with the Sultan of Sulu retaining only colonial recognition as the "religious head" of Sulu Muslims (Wood quoted in Gowing 1983, 119). The policy of indirect rule was entirely abandoned in 1914 when the administrative act that inaugurated civilian colonial governance in Mindanao and Sulu also explicitly repealed the previous official recognition of the customary (adat) law of Muslim populations.

In what follows I illuminate the earlier colonial period in Cotabato by means of biographies of the three principal collaborating datus of the early twentieth century. These three datus have been called the "triumvirate" of Cotabato (Millan 1952, 9). While they lived contemporaneously and their careers overlapped, their major contributions to the transition from sultanate to colony occurred at different periods. I will therefore introduce them chronologically.

Datu Piang

The first and most influential of the colonial datus of Cotabato was Datu Piang. According to the hagiographic biography of Piang contained in the 1952 Cotabato Guidebook (Millan 1952), he was born circa 1850, the son of a Chinese trader from Amoy named Tuya Tan and a Magindanaon mother. Datu Adil relates the following story about the birth and boyhood of Datu Piang: "The trader Tan came to Dulawan [the capital of the Buayan Sultanate] selling China goods. He presented silks and perfumes to Datu Utu and they became friends. Datu Utu gave one of his concubines to Tan and called a pandita [religious practitioner] to marry them. The girl became pregnant but Tan went off trading and never returned. The child that was born was unique—it had fair skin, so it was believed he was the child of Tan. He was named Piang and was an industrious child. He cultivated the

friendship of the officers of the Spanish garrison at Bakat by running errands for them." Throughout his life Piang was unashamedly aware that he had little or no noble blood in his veins. The 1952 biography notes that he never used the honorific "datu," instead calling himself "Ama ni Mingka" (or its shortened form "Amai Mingka"), or father of Mingka, the name by which he is still best known among the Magindanaon.[6]

Piang became a fast-rising protégé of Datu Utu, the Sultan of Buayan, who made him his "Minister of Lands" (Ileto 1971, 63). By 1890, however, the Spanish tactic of establishing forts in Cotabato to dissolve local lines of communication had proved successful and Datu Utu's inged was encircled, cutting him off from all sources of slaves and firearms (Ileto 1971). Piang as well as other of his lieutenants broke with Datu Utu when he was no longer able to provide them with firearms (Ileto 1971). Oral tradition relates that Utu's other followers deserted him in favor of Datu Piang because they could no longer tolerate his cruelty (see also Millan 1952). Piang very quickly replaced Datu Utu as the most powerful datu in the upper valley by forming an impressive alliance that included Utu's most forceful former confederates. Utu retired downriver to "spend his last years under Spanish protection" (Beckett 1982, 399).

Piang also quickly allied himself with Spain and sought the goodwill of Spanish authorities. His turugan (palace or stronghold; literally "sleeping place") was a short distance from the new Spanish fort at Reina Regente (just south of present-day Datu Piang). The fort provided him a shield from his Magindanaon enemies while he supplied its garrison with foodstuffs in exchange for cash (Ileto 1971; Beckett 1982). Equally important were Datu Piang's downriver ties in Cotabato town, particularly with Chinese traders. Beckett cites a 1901 American dispatch reporting 204 Chinese in the town of Cotabato, primarily engaged in the export of rice, beeswax, coffee, almaciga, and gutta-percha, the aggregate value of which was estimated at 150,000 Mexican dollars (1982, 402). Most of these products originated in upriver areas under the command of Piang, who apparently controlled both their production or collection as well as the terms of their export via Chinese merchants. Another contemporary American chronicler, Najeeb Saleeby (see below) reported that by "the time of the Spanish evacuation [Piang] had become the richest Moro in Mindanao and the most influential chief in the island" (Saleeby 1908, 292).

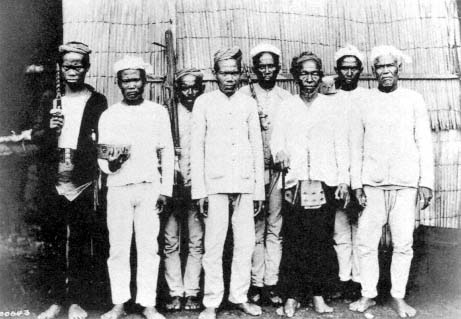

3.

Datu Utu (seated center) with his wife, Rajah Putri, and retinue, circa 1890.

This photograph was probably taken on the occasion of the elderly Utu's move

downriver to live under Spanish protection in Cotabato town in 1890. Datu Utu's

severely crossed eyes may be the source for some of the stories told about

his fierce appearance. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

Piang's loyalty to Spain lasted just as long as the physical presence of Spanish soldiers. With the Spanish evacuation of Cotabato in 1899, the men of Piang and his allies sacked Cotabato town, and a number of Christian Filipinos were killed or forced to flee. The Cotabato Chinese remained under Piang's protection and were spared. Ileto (1971) reports that Piang also declared himself Sultan of Mindanao in spite of his lack of genealogical precedent. Whether or not Piang made such a formal declaration it appears clear that at that point he was the effective ruler of Cotabato.

Piang's independent leadership of Cotabato lasted only a few months. The American occupying forces arrived in late 1899, and within a short time Piang was on his way to becoming—as described in his 1952 biography—"America's Great Friend" (Millan 1952, 292). One of the early significant services rendered by Piang to the

Americans was his assistance in eliminating the threat to American policies posed by his son-in-law, Datu Ali, the highborn nephew of Datu Utu. Between 1903 and 1905, Datu Ali led the only large-scale armed resistance to American rule in Cotabato.[7] Ali commanded a large number of armed followers, was skilled in guerrilla warfare, and, as heir apparent to the sultanate of Buayan, seemed capable of mobilizing the entire upper valley in revolt against the Americans. Datu Piang provided the intelligence that allowed Ali, stricken with malaria, to be surprised and slain by American soldiers. Oral tradition asserts that the Americans obtained Piang's assistance only by torturing him. Nevertheless, as Beckett points out, "Ali's death saw [Piang] on the winning side, the authorities in his debt, and his aristocratic rival out of the way" (Beckett 1982, 401).

By 1908, Cotabato was reported to be the most peaceful district in the Muslim Philippines, due in large part to the influence of Piang (Mastura 1979; Beckett 1982). Piang was also exceptionally responsive to American programs. The great majority of high-ranking datus were deeply distrustful of Western education and, when told they must have their sons educated at colonial schools, sent slaves in their place.[8] Piang, however, sent his own sons all the way to Manila to study (Beckett 1982). He also supported the settlement of Christian immigrants from northern islands and the establishment of agricultural colonies, which began in 1913 (Thomas 1971).

In 1915, with the end of the tribal ward system and the establishment of colonial administration in the South similar to that in the rest of the colony, Datu Piang was appointed as the only Muslim provincial board member for what was now the province of Cotabato. In the following year he was appointed to the National Assembly by the American governor general. These two positions had few formal responsibilities and conferred virtually no legal authority. They were, however, emblems of official American recognition of Piang as the preeminent leader of Cotabato Muslims as well as incentives to assure his continued cooperation with the now expressly stated colonial policy of integrating Muslims into the national political structure.

The political potency achieved by Datu Piang through his association with the armed might of the Americans, and before them the Spaniards, was symbolized by Magindanaons in their representations of Piang's index finger as supernaturally efficacious. According to Datu Adil: "It is said that the index finger of Piang was magical. If he pointed it and said 'enemigo,' people were killed; if he said 'amigo'

4.

Datu Piang (front row, second from right, with cane) and his officials and attendants,

circa 1914. Despite his quite considerable wealth and power, Datu Piang is reported always

to have dressed quite simply, in contrast to the more elaborate attire worn by most

Magindanaon datus of the period (see, for example, the dress of Datu Utu in Figure 1). The

datu's attendants include two kris bearers, a kampilan (long sword) bearer (second from left,

rear), and two men carrying brass containers for betel nut. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

they were saved. He was feared because of that."[9] Piang's economic achievements under American rule were comparably impressive. He continued his lucrative connections in the Chinese-controlled export trade while expanding into rice-milling and lumber (Beckett 1982). He also maintained his base in the upper valley and by 1926 was reported to have accumulated massive wealth that included "42,000 coconut trees (they are good for $1 per tree each year) thousands of carabao [water buffalo] [and] thousands of hectares of rice land . . . to say nothing of the tithe paid him by his loyal subjects."[10]

Evidence from various sources suggests that Datu Piang was an exceptionally shrewd and independent-minded collaborator, ever mindful of the opportunities for personal gain made available through his

gatekeeper role. A 1906 letter from the American governor of the Moro Province to the district governor of Cotabato expresses anger and exasperation at Datu Piang's attempt to collect rent from the superintendent of schools for the use of a school building that Piang had constructed in his inged at Dulawan. The letter states in part: "You will tell him, furthermore, that if he and his people cheerfully paid the cedula [head tax] and other taxes due from them to the government, we would ask from him no such assistance, but that in view of their dereliction in this and in view of the further reasons set forth above, it is believed to be a fair proposition that he should give the free use of this building for school purposes" (Bliss to the district governor of Cotabato, August 14, 1906, quoted in Gowing 1983, 198). Datu Adil tells of a road that Datu Piang contracted to build for the Americans across a swampy tract in the upper valley for twenty thousand pesos: "Piang called on his [client] datus to assist him. They arrived with their followers and enough food to feed them. The road took more than two months to build but Piang never shared any of the money he received with his datus."

These stories illustrate how collaborating datus were often able, relying on traditional power relations, to call out corvée labor in order to avail themselves of new opportunities to enrich themselves during the early colonial period. Datu Piang seems to have been more successful at this strategy than any of his contemporaries. He died in 1933 at the approximate age of eighty-four (Millan 1952). Five of his sons became either politicians or professionals.

In 1918, Piang's niece, Bai Bagungan of Buluan, became the first female municipal district president (a colonial-era post comparable to mayor) in the Philippines. Though her late husband preceded her in the post, she did not automatically succeed him. Shortly after her husband's death she married a younger man of much lower status who had served in his household. Datu Piang was furious that he had not been consulted in the matter and ordered the couple confined in the provincial jail to force Bagungan to change her mind. She remained steadfast and Piang eventually gave way and sanctioned the marriage. When the datu appointed by Piang to fill the municipal post resigned, Bai Bagungan was appointed municipal district president after receiving an overwhelming vote of confidence from the male electors of the district. Bai Bagungan was an active official who, in the words of Philippine Governor General Cameron Forbes, "became a vigorous partisan of public schools, especially for girls, and in other ways a

valuable influence in the extension of American administration in Mindanao" (Forbes 1928).[11]

Datu Ignacio Ortuoste

Datu Ignacio Ortuoste was the most extraordinary member of the Cotabato triumvirate in that he was entirely a product of colonialism. His career, which spans the years between 1904 and 1935, illustrates most dramatically the disjunctions wrought by colonialism in Cotabato. There is very little written information available on Datu Ortuoste. Beckett (1982) does not mention him and Gowing (1983) assumes him to be a Christian Filipino. According to Datu Adil, Ortuoste was neither a Christian Filipino nor a Magindanaon nor originally from Cotabato. He was a Maranao from the Lanao Plateau who was captured as a child in a skirmish between Spanish soldiers and Maranao warriors. He was brought to the Jesuit mission at Tamontaka, on the south fork of the Pulangi River. There he was reared and educated, baptized and given a Christian name.[12]

Like his contemporary Datu Piang, Ortuoste made a very successful transition from Spanish to American rule. Unlike Piang, his main assets were his ability to read, write, and speak Spanish as well as local languages, and his familiarity with colonial as well as local culture. Utilizing these attributes, Ortuoste became a highly effective intermediary between the local representatives of colonial authority and those who militantly resisted that authority. His singular personal background made him an ideal cultural and political broker, negotiating the subjugation of defiant local leaders to an occupying foreign power.

The first reported occasion for Ortuoste's mediation occurred in 1904 when he reportedly played a prominent role in dissuading Datu Ali from attacking the American military garrison in what was then the town of Cotabato (Millan 1952). Ortuoste's next recorded assignment for the Americans was in 1914, when he assisted in negotiating the surrender of Datu Alamada, an Iranun insurgent who had fought the successive colonial regimes for twenty years in the mountainous area between Cotabato and Lanao with a force of more than five hundred men (Gowing 1983).

American administrators again sought the assistance of Ortuoste in 1923 as a mediator in the surrender of another Iranun insurgent, Datu Santiago, the last leader of resistance to American rule in Cotabato. Santiago had rebelled against the imposition by the Americans of a

head tax (cedula ), the compelling of Muslim girls to attend Christian schools, and the practice by school authorities of using forced labor without compensation to construct and repair school buildings (Hurley 1936; Tan 1982). Datu Adil remembers stories told by Ortuoste that, in this instance at least, he played a double role, simultaneously assuring colonial authorities of Santiago's imminent surrender and advising Santiago on the concessions he should demand from the Americans in return for his submission.

At some point after this, Datu Ortuoste was accorded the title Datu sa Kutawatu (Datu of Cotabato) by Sultan Mastura, who was installed as Sultan of Magindanao in 1926. Sometime after helping secure the surrender of Datu Alamada he was also appointed assistant to the governor of Cotabato.[13] In his political career, Datu Ortuoste enjoyed considerable influence among colonial administrators and gained the recognition of the Muslim elite of Cotabato. He accumulated large tracts of property in and around Cotabato City before he died, sometime before 1952. Two of his sons became civil servants in Cotabato.

That Datu Ortuoste was, in all important respects, a colonial creation is evidenced in the exceptional title bestowed upon him by the reigning Sultan of Magindanao. The office of Datu sa Kutawatu was unusual not only in that it was newly created—the creation of new royal offices was uncommon but not unheard of (see below). It was also the first traditional title that in its very nomenclature acknowledged colonial domination. "Cotabato," after all, was the Spanish and American term for the territory locally known as Magindanao. As the ceremonial Datu sa Kutawatu; Datu Ortuoste personified the new colonial construct called Cotabato. He was the first purely colonial datu.

Datu Sinsuat Balabaran

After Datu Piang, Datu Sinsuat Balabaran was the most influential indigenous ruler of the American period. He was the central consolidating figure in a three-generation dynastic line that began with his uncle, the nineteenth-century Datu Ayunan—described in a contemporary account as belonging "body and soul" to the Spaniards (Rincon 1894 quoted in Ileto 1971, 92)—and extends to his sons, three of whom at various times in the past thirty years have held the most powerful political positions in Cotabato.

Datu Sinsuat was the son of Balabaran, the younger brother of Datu Ayunan. Ayunan led the pro-Spanish, anti-Utu faction in the mid1880s. Saleeby (1908) suggests that because Ayunan was much lower in rank than Datu Utu he intended to use an alliance with Spain to strengthen his own position. Datu Ayunan died in 1898, just at the close of the Spanish period. Before he died he passed on to his brother Balabaran the title gobernadorcillo del delta (petty governor of the delta), an office conferred on him by the Spaniards and one that he dearly prized (Ileto 1971; Beckett 1982).

There is little historical information on Balabaran. Datu Adil recalled a story about his demise: "There is a legend that Datu Balabaran was devoured by crocodiles because he tried to proclaim himself sultan. Balabaran had gathered his datus and told them to assemble at Dimapatoy for his proclamation. The crocodiles overheard this and ate him. They knew he had insufficient maratabat to rule as sultan, so they punished him for his brashness. Only one forearm was found. It was taken to his inged at Taviran [near Dinaig] and buried."[14]

Datu Sinsuat was born in 1864 and his political career spanned the entire American colonial period. His official biography states that as a boy he was adopted by Datu Piang and that as a young man he served as "a delegado of the Spanish Military Governor" (Millan 1952, 296). In 1916 he was appointed municipal district president of Dinaig, his home territory. Between 1923 and 1931 he served as special adviser to the governor of Cotabato Province.

Datu Sinsuat's ascent to power was due almost entirely to his close cooperation with colonial authorities. His prominence among Cotabato Muslims was achieved in part by strategic marriages designed to cement relationships with influential allies and elevate the status of his children.[15] He did not attain a preeminent position among Cotabato Muslims until the death of Datu Piang, a man in whose shadow he had long remained (Beckett 1977).

Sinsuat was also engaged in economic endeavors that included control of smuggling and gambling operations in his municipality and the acquisition of large tracts of land for cattle raising and coconut farming. Having secured his economic and political base in Dinaig, Sinsuat moved to Cotabato town, the seat of provincial government, during his tenure as assistant to the governor. As a colonial center since the late nineteenth century, the former capital of the Magindanao Sultanate had been without effective traditional rule for some time. The

current sultan and high nobility of Magindanao lived, most of them in much-reduced circumstances, either north of town across the river in Nuling or even farther away across Ilana Bay in Sibugay. Datu Sinsuat used his affinity with colonial authorities to expand his sphere of influence from the neighboring municipality of Dinaig and fill that void.[16]

While in Cotabato town, Sinsuat reportedly derived a considerable proportion of his income from the levying of traditional fines. Such practices had apparently become so widespread among datus who had been appointed as local officials in the colonial government that they were specifically prohibited in a 1935 directive from the Director of Non-Christian tribes: "It has come to our attention that in certain districts inhabited by Mohammedans, provincial and district officials and employees . . . taking advantage of their official positions, try and adjudicate the so-called religious cases. Such officials, it has been reported to us, when trying those cases impose fines upon the persons involved, collect those fines which they keep and appropriate for themselves and in those cases where the fines cannot be satisfied, the persons concerned are imprisoned and required to work for their personal benefit. This practice is not sanctioned by any of our laws."[17]

Datu Sinsuat was the first of the colonial datus to develop considerable political connections at the national level. In 1934 he was appointed to the Philippine Senate. That appointment was likely the result of his acquaintance with Senator Manuel Quezon, soon to be the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth. For some time, Quezon had cultivated the support of a few datus whom he could reasonably rely on to be supportive of Philippine independence, a position opposed by most Philippine Muslims, who feared (with good reason) the prospect of direct rule by Philippine Christians (Thomas 1971). Datu Sinsuat, in his political career, pursued a strategy that resembled that of his uncle Ayunan, who consolidated a strong traditional following and local base before moving on to expand his political power "within the framework of submission to the colonial master" (Ileto 1971, 92). However, Sinsuat far surpassed Ayunan in his success at advancing the myth of his own nobility and that of his descendants and antecedents. It was a myth directed at both Cotabato Muslims and Christians as well as at the colonial rulers. We find evidence for it in an excerpt, entitled "A Man of Royalty," from a ceremonial volume presented to Elpidio Quirino, the second president of the Philippine republic, shortly after Datu Sinsuat's death in 1949:

The name Sinsuat in Cotabato and for that matter the whole length and breadth of Mindanao is more than the mere inference of a family name . . . For the fact is that the brand Sinsuat is a family dynasty that conjures in the trained mind a nobility, a well-guarded family tradition encased in honor and fame, imbedded in illustrious and amazing achievements, silkened in the tender and luminous carpet of distinction and treasured by the glorious and exemplary exhilarating breeze and potency of fame and honor . . . And the history of this family name is as old as the history of Mindanao itself. To speak of a Sinsuat is almost a temptation to call it Mindanao in rabid generalization.

Beneath the breathless hyperbole may be found an unmistakable instance of nobility by assertion, a modern variant of what Beckett has described for the precolonial period as the "post hoc ennoblement of the powerful" (1982, 398).

Colonial-Era Datus and the Continuation of "Traditional" Rule

The careers of the "Cotabato triumvirate" provide the basis for assessing the effect of American colonialism on indigenous political and economic relations in the Cotabato Basin. The biographies indicate, first, that the colonial datus generally had only tenuous ties to the high nobility of the Cotabato sultanates, and some had none at all. While the old high nobility was permanently devitalized by the colonial order—surviving only as dignitaries—the "new datus . . . created their own maratabat [rank honor]," as well as purchased it for their children through intermarriages with noble families, often facilitated by extraordinarily high bridewealth payments (Beckett 1982, 408). This process is clearly evident in the dynasty-building careers of Piang and Sinsuat.

The new datus of the colonial period were able to enhance their traditional status because of the power and wealth they had obtained through collaboration with American colonial authorities.[18] With the early abandonment of the policy of indirect rule, their political positions were not predicated on any official American recognition of their traditional right to rule Cotabato Muslims. Instead, they were bestowed with new ceremonial offices—as municipal district president, assemblyman, or (occasionally) senator—as tokens of their political ability to mediate between ordinary Magindanaons and an alien colonial authority, and as rewards for their political willingness to ensure

Muslim compliance with colonial aims. In return for these services they received, besides the trappings and privileges of office, the opportunity to exploit new potential sources of wealth. They also retained control over the agrarian sector during the colonial period. They were none the less a dependent and sectional elite. Commerce was almost entirely controlled by the Chinese, and public administration remained exclusively in the hands of Christian Filipinos (Beckett 1982).

Despite their diminished political autonomy the new datus were able to amass significant wealth. We have seen that Datu Piang greatly increased his wealth under the Americans and that Datus Ortuoste and Sinsuat gained theirs. Some of this wealth, such as that derived from the imposition of fines and the drafting of corvée labor for colonial projects, resulted from the extension of traditional relations to new contexts. Other sources were novel, such as datus' advantaged opportunities to create or acquire private property. Another source, neither traditional nor entirely new, was the intensification of agriculture. In 1908, exports from Cotabato were reported at 21,246 pesos. In 1911 they were 311,043 pesos, and in 1919, 760,428 pesos (Forbes 1928, 28; Beckett 1982, 403). Rice was the most important item in this dramatic expansion of exports, followed by copra and corn. Between 1920 and 1935, the area under rice cultivation increased from 1,864 hectares to 24,630 hectares (Beckett 1982, 403).[19]

It seems unlikely that the expansion of rice production in colonial Cotabato followed the pattern that occurred either earlier in the mainland deltas of Southeast Asia or simultaneously on the Central Luzon Plain. In those cases expansion was accomplished by rural smallholders or tenants with capital advanced by landlords, mill owners, or middlemen (the latter two often Chinese) and involved the restructuring of traditional production relations. Because commercial rice production had existed for some time in Cotabato, and because private property in land was not well established until after 1930, it is more likely that the expansion of rice production in the early American period occurred within the traditional production relations established between datus and their subordinates. Despite the abolition of slavery, many datus of this period retained their existing banyaga slaves and continued to acquire debt-bondsmen (Beckett 1982). Datus also maintained control over the endatuan subordinates who comprised their ingeds. It seems reasonable to imagine that datus responded to the new commercial opportunities of the American period in the same way they reacted to the earlier demand for foodstuffs to supply Spanish garrisons—by intensi-

fying agricultural production to the extent of their capabilities.[20] Although the exact outlines of the intensification process are not known (Chinese merchants did own rice mills and may have made crop loans directly to producers), it is likely that datus were the major beneficiaries of the agricultural expansion of the early American period.

The wealth and political connections of the new datus were used to launch family dynasties. Generally, this was accomplished by their acquisition of a mix of old and new durable resources. They secured new resources such as tracts of land and other productive property, new commercial connections, new extralocal political patrons, and new colonial educations for at least some of their sons. They were also careful to secure more traditional sorts of resources: political allies and subordinates and, just as important, maratabat (rank honor) for their children and grandchildren by obtaining high-ranking wives for themselves and their sons.

One of Datu Piang's sons became the first Magindanaon attorney. Two others obtained college educations and became politicians. However, with the death of the most dynamic of these sons, Congressman Gumbay Piang, in 1949, the dynasty was irreversibly weakened, and the Piangs are no longer a powerful political force outside their home municipality. The Sinsuat family dynasty has exhibited the most political endurance. The sons of Datu Sinsuat have held positions as congressman, governor, and mayor (of Cotabato City and Dinaig), and continue to be powerful players in regional politics. The sons of the non-Magindanaon Datu Ortuoste were, predictably, an exception. They chose Philippine Christian culture (their mother was almost certainly a Christian), were educated in Manila, and became local civil servants. The family dynasty founded by Datu Ortuoste thus became a Christian one and the title of Datu sa Kutawatu lapsed with his death.

As the colonial-era datus established their names and consolidated their local political domains they invariably embraced the myth of sanctified inequality. They came to regard themselves as a traditional nobility, as the legitimate successors of the precolonial rulers of Cotabato. This accentuation of ancient roots and illustrious bloodlines was not only (or even primarily) for the benefit of Magindanaon subordinates. As illustrated colorfully in the portrayal of Datu Sinsuat as "A Man of Royalty," it was also intended to impress American colonial agents and Christian Filipino nationalists by confirming their preconceptions about the continued importance of a potent and exotic Muslim nobility.

Colonial Agents and the Constitution of Moro Identity

An inconsistency may be evidenced in American colonial policy toward Philippine Muslims that was at least partly occasioned by the "self-liquidating imperialism" that formed the basis of America's overall Philippine colonial policy. After their brief experiment with indirect rule, American colonial authorities explicitly refused any formal recognition of the aristocracies of the Philippine sultanates or of indigenous legal systems. Muslims were not to be excepted from direct colonial rule; close American supervision was required in order for Philippine Muslims to achieve a level of "civilization" sufficient to allow their integration with their Christian counterparts in an eventual Philippine republic. Despite the official denial of traditional rights of rule, however, American colonial agents came to place great emphasis on the Muslim nobility as implementers of colonial policies intended specifically for Philippine Muslims.

Throughout the course of American rule in the Philippines, a particular set of policies was formulated in reference to a category of colonial subjects denominated as "Moros." Although official American attitudes toward Philippine Muslims lacked the holy war complex that prompted the Spanish use of that designation (and despite the fact that the term was well established as a pejorative among Philippine Christians), American authorities adopted the usage "Moro," with all of its conglomerating and epithetic connotations, as the exclusive term of reference for the entire thirteen Muslim ethnolinguistic groups of the Philippines. It is nearly impossible to find in official documents, even among the writings of the most sensitive American observers, any clear indication of the distinct histories and cultures possessed by the various subject peoples designated as "Moros."[21]

One of the most influential agents in the early American colonial administration of Philippine Muslims was Najeeb Saleeby, a Syrianborn physician who came to the Philippines as a U.S. Army doctor in 1900 (Thomas 1971). Saleeby was assigned to Mindanao and became fascinated with its Muslim inhabitants. He made the acquaintance of numerous prominent Muslims and learned two local languages—Magindanaon and Tausug. He used his knowledge of those languages, and of Arabic, to translate entitling genealogies (tarsila, salsilah ) and law codes (Luwaran) for the main sultanates of the region, including the Magindanaon and Buayan Sultanates. Saleeby was quickly recognized

by colonial authorities as the resident American specialist on Philippine Muslims and in 1903 was appointed Agent for Moro Affairs. In 1905, the same year he published his Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion (the first scholarly work on Muslim Filipinos published in English), he became the first superintendent of schools of the Moro Province.

Saleeby opposed the move to direct administration of the Muslim regions of the South and, though overruled, he was instrumental in conditioning official attitudes about the governance of Philippine Muslims, and particularly about the utilization of traditional Muslim elites to implement colonial policy. Saleeby's views on the "development" of the Muslims of the Philippines were expressed most cogently in a 1913 essay entitled The Moro Problem .[22] In that work he disputes the popular perception of Moros as savages and religious fanatics. Moros, he observes, "have so little religion at heart that it is impossible for them to get enthusiastic and fanatic on this ground" (1913, 24). Moros do, however, possess relatively sophisticated, if "feudal," political communities ruled by datus. "The datu is God's viceregent on earth. He is of noble birth and the Prophet's blood runs through his veins. The people owe him allegiance and tribute" (1913, 17). He notes further that, for the most part, the datus had not been actively opposed to American aims and that "religion has never been a cause of conflict between Americans and Moros"(1913, 24). Moreover, "the Moros are greatly disunited . . . [E]ach district is inhabited by a different tribe and these tribes have never been united" (1913, 15). It is in the Americans' interest, in fact, to unite the Moros under their traditional leaders in order to initiate a "process of gradual development" (1913, 17). In furtherance of such a goal Saleeby, himself a Christian, declares that "religion" (meaning Islam) "can be encouraged and promoted" for the benefit of both the colonial government and the Moro people (1913, 24). As envisioned by Saleeby, with the reestablishment of "datuships" and "Moro courts," "the individual Moro would find himself well protected and would become more thrifty and intelligent. Moved by a natural tendency to imitate superior civilization, he would unconsciously reform his customs and home life and gradually acquire American ideas and new ambitions. An enlightened Moro community, wisely guided by efficient American officials, would undoubtedly work out its own destiny, and following the natural law of growth and development would gradually rise in wealth and culture to the level of a democratic [meaning Philippine Christian] municipality" (1913, 30).

In these remarkable passages, Saleeby outlines nothing less than the colonial genesis of Morohood. Saleeby was more knowledgeable about the history, culture, and contemporary political culture of the separate Muslim peoples of the Philippines than any other colonial administrator. He knew that the various Muslim ethnolinguistic groups were in no sense united, nor did they possess—jointly or individually—a politically potent oppositional Islamic consciousness. He urges the promotion of Muslim unity, not through the preservation or restoration of individual traditional polities (i.e., by means of straightforward indirect rule), but through the formation of a new transcendent Philippine Muslim identity: through the development of Morohood.

In his essay, Saleeby proposes the creation of Muslim unity for the sole purpose of propelling Philippine Muslims along a path of development parallel to that of Christian Filipinos in order to prepare their eventual integration into an inevitable postcolonial Philippine nation. They should be led on that path by members of their traditional nobility because, regardless of American attitudes toward aristocracies, the Muslim populace affirms their indefeasible right to rule by fact of their hallowed ancestry.[23] Saleeby's account of Muslim political culture accentuates the myth of sanctified inequality and couples it with Morohood. Islam should be encouraged by colonial authorities because it is that which binds the Muslim populace most indelibly to their leaders—leaders who for the most part have been inclined toward cooperation rather than confrontation with the American regime. Moro religion, law, and customs do, of course, require rationalization by imitation of "superior" culture. Through that process of rationalization by imitation, American principles working on this distinct Philippine population—unique primarily because it had not experienced three hundred years of Spanish colonial rule—would achieve an outcome analogous to that devised for Christian Filipinos.

Although Saleeby's specific proposals were never formally incorporated into colonial policy toward Filipino Muslims, many of his recommendations substantially influenced the attitudes and practices of key colonial administrators.[24] Among those was Frank Carpenter, the first governor of the Department of Mindanao and Sulu, who took office in 1914 shortly after the publication of Saleeby's essay. Carpenter expressed his views in a 1919 letter to the colonial secretary of the interior requesting that Princess Tarhata Kiram, the adopted daughter of the Sultan of Sulu, be sent to the United States as a government student. After reporting the "generally accepted" conclusion that it is "practically

futile to attempt the conversion of "a Mohammedan people as such to Christianity," Carpenter restates Saleeby's suggestions about guided development through the agency of Muslim notables.

[It] is essential to the efficiency, commercially as well as politically, of the Filipino people that all elements of population have uniform standards and ideals constituting what may well be termed "civilization"; and as the type of civilization of the Filipino people in greatest part is that characteristic of the Christian nations of the world, the bringing of the Sulu people from their primitive type of civilization to the general Philippine type may be stated as the objective of the undertaking of the Government in its constructive work among them. No more effective and probably successful instrumentality appears for this undertaking than the young woman who is the subject of this communication.

In suggesting particular arrangements for the American education of the princess, Carpenter goes on to list two considerations of "fundamental importance":

That she be not encouraged nor permitted to abandon her at least nominal profession of the Mohammedan religion, as she would become outcast among the Sulu people and consequently her special education purposeless were she to become Christian or otherwise renounce the religious faith of her fathers. . . .

That she be qualified to discuss intelligently and to compel respect from the Mohammedan clergy she should be encouraged to read extensively and thoroughly inform herself, so far as possible from the favorable point of view, not only the Koran itself and other books held to be sacred by Mohammedans, but also the political history of Mohammedanism.[25]

James R. Fugate, the American governor of Sulu from 1928 to 1936, also acted upon Saleeby's suggestions by implementing colonial policies through individual Sulu datus (Thomas 1971, 189). No colonial administrator was more apparently influenced by the views of Saleeby than Edward M. Kuder, who, beginning in 1924, spent seventeen years as superintendent of schools in the three Muslim provinces of Cotabato, Lanao, and Sulu. Like Saleeby, Kuder endeavored to learn local languages and eventually gained proficiency in Magindanaon, Maranao, and Tausug, the languages of the three main Muslim ethnolinguistic groups of the Philippines.

Kuder expressed his views on the education of Philippine Muslims in a 1935 report to the Educational Survey Committee on "the present education of the non-Christian Filipinos," observing that "[t]he chief value . . . of education among the non-Christians has been the

establishment of a linking element among them, very close in thought, feeling and national identity with the country as a whole, while still conscious of the good things in its own cultural background."[26] Writing as the Philippines were about to be granted partial independence (see below) and amid growing Western concerns about Japanese aggression in Asia, Kuder proposes an additional potential political benefit (one not articulated by Saleeby) to be obtained from the education of Muslims. "Through the proper treatment and education" of Philippine Muslims, valuable ties may be established with neighboring Malay nations (all still under Western colonial tutelage), forging a regional compact able to withstand "alien" (i.e., Japanese and Chinese) forces: "And here lies the hope of the Philippines for survival—coalition into eventual Malay solidarity . . . And here lies the value of . . . maintaining . . . by means of education, that linking element of non-Christian Filipinos . . . [F]or this Non-christian Filipino element is largely Mohammedan and the great Malay races . . . are overwhelmingly Mohammedan—not the gloomy and fanatic faith of Arabia, but tempered and moderated by the genial Malay hospitality and courtesy and hence compatible, through a proper and common education, with the Christian Philippine civilization."[27]

Kuder put Saleeby's ideas about datu-led development into practice by undertaking personally the training of a generation of Philippine Muslim leaders. In his travels throughout the Muslim provinces he sought out honors students (all of them boys) from various Muslim groups, most usually the sons of datu families, and fostered them, bringing some of them to live under his roof to be tutored by him. In this manner, Kuder personally educated a considerable number of the second generation of Philippine Muslim leaders of the twentieth century. Datu Adil, who had a distinguished career as an officer in the Philippine Constabulary, was one of Kuder's students. He recalled with fondness his time spent as Kuder's "foster son" fifty years earlier, recollecting that he was "strengthened by Mr. Kuder's discipline." In the course of one of our conversations Datu Adil produced a treasured keepsake, a beautifully bound volume of Burton's translation of The Thousand and One Nights . Mr. Kuder had presented the complete set to him when he left the University of the Philippines, telling him it was important that he appreciate his religion.

In a scholarly paper (entitled The Moros in the Philippines ) published in 1945 on the eve of full formal independence, Kuder looked back on his accomplishments. He observes initially that the term "Moro" is an exotic label affixed by Europeans to Philippine Muslims

in general and one not used among them. He also notes, echoing Saleeby, that more than three centuries of Spanish hostility had failed to bring about an overall alliance among the separate Muslim societies of the Philippines. There follows a revelatory passage: "Within the decade and a half preceding the Japanese invasion of the Philippines increasing numbers of young Moros educated in the public schools and collegiate institutions of the Philippines and employed in the professions and activities of modern democratic culture had taken to referring to themselves as Mohammedan Filipinos" (Kuder 1945, 119). Kuder is here referring indirectly, but with detectable pride, to his protégés, the Muslim students he brought together and personally trained in his seventeen-year career prior to World War II. These young men, he avers, are the very first generation of Muslims in the Philippines to possess a shared and self-conscious ethnoreligious identity that transcends ethnolinguistic and geographical boundaries. Kuder's statement is an oblique assertion that he had accomplished in less than two decades what Spanish aggression was unable to provoke in more than three centuries. He had developed a core group of "Mohammedan" Filipinos. The use of that most emblematic of Orientalist terms suggests that the content of this new shared identity had been at least partly formed by his instruction.

It is apparent that Kuder, following Carpenter's lead, not only educated his students in the arts of "modern democratic culture" but also encouraged them to approach Islam (in Carpenter's words) "from the favorable point of view"—that is to say, through the eyes of Western arts and sciences. That at least some of Kuder's students referred to themselves as Mohammedans is attested to by the formation in 1932 of the "Mindanao and Sulu Mohammedan Students' Association," a small organization composed of Philippine Muslim students at the University of the Philippines in Manila, many of them former students of Edward Kuder. In a 1835 letter to Joseph Ralston Hayden, the then vice-governor general of the Philippines, Salipada Pendatun, Kuder's star pupil (see below) and a principal organizer of the association, described its aims: "Our primary purpose in view is to act as the unofficial representative of our people at home; in order to protect their rights and interests, to help them realize the value of education; to inculcate in them the value of cooperating with the leaders of Christian Filipinos in working for the common welfare of the country."[28]

Kuder's aim was to create an educated Muslim elite trained in Western law and government and able to represent their people in a single Philippine state—a cohort ready to direct Muslim affairs through

enlightened forms of traditional rule. That goal was realized in great measure in the careers of Kuder's students. Most became lawyers, civil servants, and politicians; married Christians; and remained formally monogamous. At the same time, they conserved their traditional roles as Islamic adjudicators in what were now nongovernmental tribunals and as sources of moral authority.

Datu Salipada K. Pendatun

The most prominent of Kuder's former students in Cotabato, and one of the most successful of any of his "foster sons," was Salipada K. Pendatun.[29] Datu Pendatun (more commonly known as Congressman Pendatun) became one of the most nationally prominent and influential of the postcolonial datus of Cotabato. Pendatun was born in 1912 at Pikit, Cotabato, of noble parentage. His father, the Sultan of Barongis, a small upriver sultanate, died when he was still a boy and Pendatun was brought to live with Edward Kuder, becoming one of his first students. Pendatun retained a close relationship with his former teacher until Kuder's death in the early 1970s.

After leaving Kuder's tutelage, Pendatun studied law at the University of the Philippines in Manila. In 1935, the Philippine Islands were granted partial independence under Commonwealth status by the United States, with the promise of independence in ten years' time. In that year, Pendatun, still a law student, wrote another letter to Vice-Governor General Hayden noting the rush of immigrants to Cotabato induced by the Commonwealth's new road-building policy and the increasingly disadvantaged position of Muslims vis-à-vis Christian settlers in attempting to acquire public lands. He urged (unsuccessfully) that a special agent be appointed to help Muslims with the registration process (Thomas 1971). Datu Pendatun graduated from the University of the Philippines in 1938 (the first Magindanaon to do so) and was appointed by Philippines President Quezon to the Cotabato Provincial Board to replace Datu Sinsuat, recently elected to the National Assembly. Pendatun was elected to the same post in 1940 (Glang 1969).

The transitional Commonwealth period of American sovereignty in the Philippines was profoundly disrupted in 1941 by the Japanese invasion and occupation. During the war against the Japanese, Pendatun led one of the most active guerrilla units in Mindanao, a group that included Americans and Christian Filipinos as well as Magindanaons. In 1942, his fellow guerrilla leaders selected him as their "General"

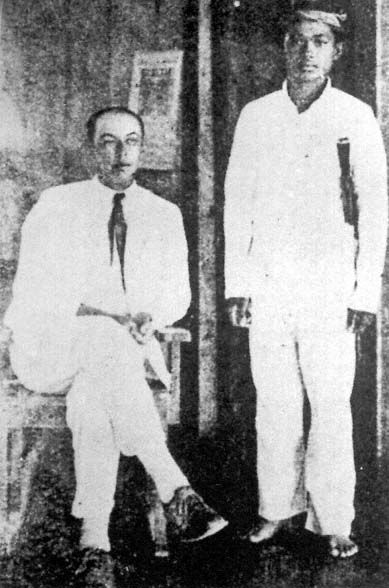

5.

Edward Kuder (seated) with the young Salipada Pendatun, 1927. Pendatun,

shown here in the simple garb of a Muslim schoolboy, was the son of the Sultan

of Barongis, as well as Kuder's foster son and star pupil. He went on to become

the most prominent and influential Philippine Muslim politician in the post-

independence period. Courtesy of Phillipines Free Press .

(Thomas 1971, 301). In recognition for his war efforts, Pendatun was appointed governor of Cotabato in 1945 by President Sergio Osmena.

Datu Pendatun's early career was one of the most successful of any of the second-generation colonial datus. He is representative, however, of a number of other Philippine Muslim political figures of his generation (some of them also former students of Edward Kuder). By the founding of the Philippine republic in 1946 they were politically well established with ties to the apparatus of national rule in Manila and able to command local allegiance on the basis of traditional social relations. This new Western-educated Muslim elite had also begun to develop a self-conscious transcendent identity as Philippine Muslims. That consciousness derived not from opposition to American rule but rather from studied adherence to its objectives.

The peculiar form of direct colonial rule established by the Americans for Philippine Muslims—combining official repudiation of the authority of traditional rulers with a wardship system for certain Muslim elites specifically designed to enhance their abilities as "Mohammedan" leaders—produced effects inverse to those found in another Southeast Asian colonial system attempting to rule Muslims. The Dutch development of adatrecht for colonial Indonesia was intended to de-emphasize Islam by "constituting local particularisms in customary law [and] favoring the traditional authority structures linked to them."(Roff 1985, 14). While Dutch policies fostered (indeed created) ethnic divisions among Indonesian Muslims, the attempts by various American colonial agents to rationalize and objectify the Islamic identities of a generation of Muslim leaders provided the basis for ethnicizing Islam in the Muslim Philippines. As we shall see, that newly cultivated Muslim ethnic identity acquired particular saliency when Muslim political leaders found themselves representing a small and suspect religious minority in an independent nation dominated by Christian Filipinos.