The Malagasy

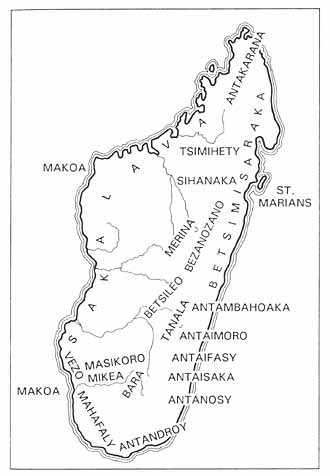

Today in Madagascar there are eighteen[1] (Covell 1987: 12) officially recognized ethnic groups (FR: ethnie,tribu; HP: foko,karazana; SAK: karazan̂a) which are relevant for census purposes (figure 3.1).

| Group Name | Population % | Group Name | Population % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1. Malagasy Ethnic Groups. Sources: Covell (1987: 12), after Nelson et al. (1973), figures from the Institut National de la Statistique in Madagascar, and Thompson (1987). Reproduced by permission of Pinter Publishers, Ltd., London. All rights reserved. | |||

| Merina | 26.1 | Sihanaka | 2.4 |

| Betsimisaraka | 14.9 | Antanosy | 2.3 |

| Betsilio | 12.0 | Mahafaly | 1.6 |

| Tsimihety | 7.2 | Antaifasy | 1.2 |

| Sakalava | 5.8 | Makoa | 1.1 |

| Antandroy | 5.3 | Benzanozano | 0.8 |

| Antaisaka | 5.0 | Antakarana | 0.6 |

| Tanala | 3.8 | Antambahoaka | 0.4 |

| Antaimoro | 3.4 | Others | 1.1 |

| Bara | 3.3 | ||

The use of the term ethnic group is problematic from an anthropological point of view, since all of these groups are actually subgroups of the general category Malagasy, whose members share common cultural elements such as language and religious beliefs. In other words, the concept of ethnicity is one of perspective and scale. Outside Madagascar, Malagasy are viewed as the dominant ethnic group of the country, and Sakalava, Merina, and other peoples are considered subgroups of this larger category. From a Malagasy point of view, however, Merina, for example, are viewed as the dominant ethnic group, and other non-Malagasy peoples (Arabs, Indo-Pakistanis, Chinese, Comoreans, and Europeans) are grouped separately as “strangers” or “foreigners” (étrangers). Since this study is concerned primarily with Malagasy peoples, I will use ethnic group as the Malagasy themselves do. These ethnic divisions are significant in everyday discourse, as Malagasy use them to define themselves in relation to each other. Ethnic groups also overlap with other categories based on geographical, economic, and religious differences.

Ethnic categories have changed over time. As Covell points out, they are flexible constructs, and although they are in part a reflection of changes in the political climate of Madagascar, it would be false to conceive of them solely in these terms:

This form of identification hardly constitutes a key to Malagasy politics. The groups themselves are riddled with internal subdivisions and several are, in fact, political constructions created from small groups in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the Merina, Sakalava, and Betsimisaraka are the most important of these. Others, such as the Betsileo and Bara were first grouped together as administrative subdivisions of the nineteenth-century Merina empire. (1987: 12)

The French also made use of these categories. They did not begin systematically to take official censuses, with Malagasy broken down into different ethnic groups, until 1949, following the 1947 revolt. This practice was continued by the government of the Malagasy Republic after Independence (1960) up until the time of the Socialist Revolution in 1972. For approximately a decade afterward, no census information was collected (publications in general came to a halt in Madagascar at this time). In the Sambirano Valley it is only in 1985 that new efforts were made to gather census data in preparation for national elections that occurred in early 1989. On these recent censuses, the ethnic categories no longer appear, although logbooks kept of Ambanja’s neighborhood residents, for example, still make note of ethnic affiliation. In everyday discourse these categories are used by Malagasy to label one another.[2]

Today certain factors unite members of each ethnic group: a shared dialect of Malagasy; similar religious customs, most notably in regard to mortuary rituals and a strong regard for local ancestors; observation of fady or taboos; characteristic regional dress; economic activities; and affiliation with a specific geographical territory (figure 3.2). These categories and their associated characteristics are used by Sakalava as they define themselves in opposition to others. Ultimately, these differences define boundaries between insider and outsider. Among some peoples the boundaries are fluid, while among others they are very rigid.

3.2. Present Distribution of Malagasy Ethnic Groups. Sources: After Brown (1978: 16); Kottak (1986, frontispiece); and Société Malgache (1973).