Dand-Bethak

Dands and bethaks are two different exercises, but together they constitute the core wrestling vyayam regimen. Dands are jackknifing push-ups and bethaks are comparable to Western-style deep knee bends. Although dands and bethaks are done separately, they are usually referred to as a pair. As a set they provide a complete body workout.

One starts a bethak from a standing position with feet set at forty-five degree angles and heels about fifteen to twenty centimeters apart. While squatting down one should jump slightly forward onto the balls of one’s feet while lifting the heels clear off the floor. In the process of standing back up, one should jump backwards to the position from which one started. One’s arms should be relaxed. They should sway with the movement of the body in order to maintain balance. One’s eyes should be fixed on a point about four meters forward on the ground, so that one’s head will be stationary and balanced. One should do about sixty or eighty bethaks per minute and between sixty and one hundred at a stretch (Atreya 1974: 25). All of this depends, of course, on the degree of one’s strength and previous experience. Similarly, the number of bethaks one does is relative to personal strength, predilection, available time, and specific goals. Well-known champions do between two and three thousand bethaks a day. Average wrestlers often do as many as one thousand. At the very least a wrestler will do between five and eight hundred per day.

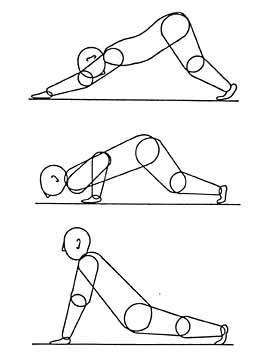

Dands are similar to certain aspects of surya namaskar. One starts a dand from a face-down, prone position with feet placed close together and palms flat on the ground directly below the shoulders about half a meter apart. To begin, one cocks the body back by lifting one’s buttocks into the air while straightening both arms and legs (see figure 2). Bending at the elbows, one dives forward so that the chest glides between the palms close to the ground. One then arches up while straightening the arms and thrusting the pelvis down towards the ground. One then recocks the body to the starting position.

According to Atreya one should do half as many dands as bethaks (1974: 21). Once one has assumed the position of doing dands one should not move until all dands are completed. A good wrestler in the prime of life can do about 1,500 dands per hour, and many do as many as 2,000 a day. Those wrestlers who swing joris and gadas as the main aspect of their routine do as many as 5,000 dands per day, but this is exceptional. Whereas bethaks are more often than not performed before jor (see below), dands are performed at the end of the morning practice session. However, there is no strict rule regarding the sequence of an exercise regimen. Many wrestlers do their dands and bethaks in the evening.

Figure 2. Dand

The most important feature of dands and bethaks is that they be done rhythmically and at a steady pace. The performance of thousands of these exercises produces a mental state not unlike that of a person who has gone into a trance through the rote recitation of a mantra or prayer. Thus, dands and bethaks transport the wrestler into an altered state of consciousness from which he derives psychic and spiritual purification. Vyayam is very much like meditation in this respect. I was told that Jharkhande Rai, a champion wrestler who used to be a member of Akhara Ram Singh, would concentrate so hard on doing his dands that his sweat would leave a perfect image of his body as it dripped onto the earth. This and similar stories were told in order to make the point that the wrestler involved was often not even aware of the extent of his exertion. Many times I have sat on the edge of an akhara and watched a wrestler bob up and down for half an hour or more without taking his eyes off an imaginary point on the ground in front of his face. It is not surprising that the beneficial effects of dands transcend the mere physical body and strengthen aspects of moral and ethical character. Atreya points out that dands strengthen the wrists, fingers, palms, neck, chest, and back. Dands also cure all kinds of illnesses relating to semen loss (impotence, infertility, and spermatorrhoea) and faulty digestion (1974: 19). Dands strengthen the sinews of the body, and they also develop character:

As one of the central exercises in a wrestler’s vyayam regimen, it is clear that dands do more than develop the gross body. They develop the personality of the wrestler as well. The wrestler’s personality derives its strength—as a charismatic social force and as personal self-confidence—through the symbiosis of a personal experience akin to enlightenment and a physical experience of muscular development. With regard to both dands and bethaks Atreya makes the following observation:Doing dands makes a person’s character and personality shine. The body takes on a powerful radiance. Not only this, but the person who does dands lives a fuller and more meaningful life. His personality is more attractive. He is liked by everyone. His whole attitude towards life is changed (ibid: 20).

Dands and bethaks make the muscles of the body so incredibly strong that the wrestler appears divine. Dands and bethaks are the mirror in which the aura of wrestling is reflected. They are the two flowers which are offered to the “wrestling goddess.” Dands and bethaks are the two sacrifices made to the goddess of wrestling. If she is pleased she will bestow great strength and turn mere men into wrestlers (ibid).