| • | • | • |

Selfhood and Personhood in the Context of Possession

Tromba possession affects identity on multiple levels. As a medium moves in and out of trance, she experiences shifts in her identity on three different levels: the first is what Mauss (1987: 2) referred to as the idea of moi or “self,” that is, her private (and psychological) sense of who she is as an individual operating in the world. The second is her “person” (personne; again, see Mauss 1987: 2ff), or what I will refer to as her social persona: how she is perceived by others within her social milieu.[1] For example, as a medium a woman elevates her social status when she becomes a healer. She also shifts from being a commoner to a royal personality. The third shift is one that is experienced by mediums who are migrants. They experience a shift in their ethnic identity, that is, their cultural persona. A complex fictive kinship system associated with tromba enables a medium to make these shifts in her social and cultural personae.

Shifting Selves

A medium, because she is a vessel or “house” (trano) for spirits, has multiple selves: her personal (unpossessed) self and each of her spirit’s selves. Thus, a medium with two spirits has, essentially, three selves. Gender is also an important elements of selfhood. As a medium she is female; when possessed, she is usually male. The boundaries between these different states of selfhood are clearly demarcated for the observer as a woman goes in and out of trance, yet these multiple selves blend into one another and carry over into her daily (unpossessed) life.

As the last chapter illustrated, spirit possession provides fertile ground on which to record and interpret collective experience. In turn a dynamic may also develop between collective and personal histories. As Brown deftly illustrates in her study Mama Lola (1991), in the context of Haitian vodou there are multiple layers of history recorded, shaped by Haitian history, generations of mediums within a given kindred, and the personalities of the spirits that possess them. As we learn through the unraveling of the personal and family history of her key informant, Alourdes, different spirits (who are African and Haitian, male and female, and so forth) are, for example, more appropriate for particular time periods, settings, and temperaments of mediums. In this way, not only is possession subjectively experienced, but history, as well, is interpreted from a subjective point of view by a medium, through her spirits. This process in turn has a profound effect on the medium’s sense of selfhood.

This overlapping of histories is also central to tromba possession. A tromba medium, as well as others around her, perceives herself as a composite or a gestalt of interlocking and overlapping selves. This is evident in the way that tromba mediums and their spirits recounted their personal histories during my interviews with them. I found that the events in mediums’ personal lives were often reflected in their versions of their spirit’s personal histories. At times, tromba stories provided a more appropriate arena for articulating a medium’s personal problems. For example, in interviews with a medium named Mariamo, I had great difficulty in collecting any details on her life. After numerous attempts one afternoon proved futile, I asked her to call up her spirits so that I might interview them. Two appeared: the first was a prostitute spirit named Mbotimahasaky, whom I quickly learned had had serious conflicts with her father, brother, and lover, and she had killed her first and only baby as a result of neglect. The second spirit was a soccer player named Djaomarengy. After these two spirits had departed, her assistant (rangahy) and I retold the spirits’ stories to Mariamo, who then explained that she herself had worked as a prostitute for sixteen years in Mahajanga. Previous to this event she had sometimes alluded to her inability to have children, but it was only during (and then after) these interviews with the spirit Mbotimahasaky that Mariamo was able to articulate the great sadness she felt about her barrenness. As I later learned, the antics of the spirit Djaomarengy usually paralleled events in the life of Mariamo’s lover, who was an avid soccer player. As this story illustrates, there is a richness in narrative form here that may allow for a deeper level of introspection than is generally possible in daily social discourse among Malagasy. In essence, mediums may in fact experience a deeper or more integrated sense of self than do non-mediums (cf. Obeyesekere 1981).[2]

The Social Persona, or Mediumship and Personhood

For Mariamo, this overlapping of selves is one that carries over into her everyday life, and which affects her social persona (person) or how she is viewed by others in her social world. Mariamo perceives herself as being composed of all of these personalities, and others do as well: she is both male and female, royal and commoner. This is especially true since she works as a healer. Even in her unpossessed state she experiences this shift, because she is respected and feared by others who are aware of her association with ancestral spirits. Possession also affects how a medium is defined structurally in relation to others. As will be made clear below, her personal relationships with kin and friends are temporarily altered as she shifts in and out of trance yet, by virtue of her being a medium, they are permanently altered as well.

Gender, Age, and Possession

Historically, the majority of mediums for tromba spirits have been adult women. At Nosy Faly, for example, saha are usually women in their forties or older, while men play complementary roles as interpreters for the spirits. In general, a Sakalava ritual cannot be performed if the two are not present and represented.[3] This is evident, for example, during activities that take place at the royal tombs on Nosy Faly. There are both male and female tomb guardians (male: ngahy; female: marovavy or ambimanan̂y), each with their specified duties. When living royalty come to pay tribute to their ancestors, both male and female guardians must participate in order for the spirits to be invoked. Similarly, when the greatest of the royal tromba spirits are consulted, both the female saha and the male ngahy must participate.

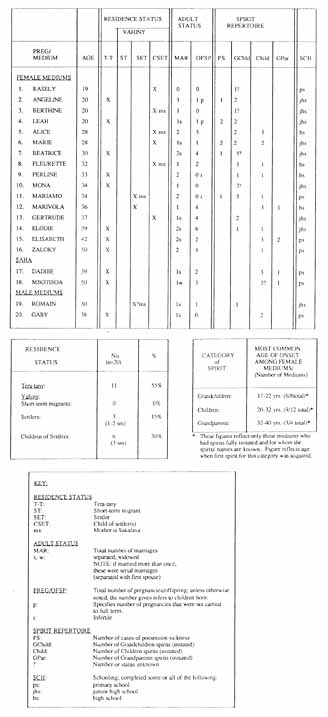

Thus, in the precolonial context, possession in Sakalava culture was not evidence of marginal status (cf. Giles 1987 on possession on the East African coast). Instead, it was a central institution associated with adult female status. Similarly, in Ambanja today, tromba possession continues to be almost exclusively a female experience. Tromba spirits may possess men, but this is unusual. Only four (of a total of ninety-eight) of the mediums I encountered throughout the course of my fieldwork were male. In addition, different categories and generations of spirits are associated with different ages and statuses. Possession sickness, involving njarinintsy and other malicious spirits, occurs most often during adolescence, their crises coinciding with troubled or failed love affairs and pregnancy outside of marriage (see chapter 9). Tromba mediumship, however, is associated with culturally sanctioned adult female status: out of eighteen female tromba mediums I interviewed in detail, nearly all had been married (by ceremony or common law) at least once before the onset of tromba, and thirteen had had at least one pregnancy that may or may not have been carried to full term at the time of having a tromba spirit instated (see figure 7.1 and Appendix A).[4] Marriage itself is the idiom that is used to describe tromba possession: a medium and her spirit are defined as each other’s spouse (vady). As will be explained below, this concept of marriage has significant implications for household dynamics. It also provides a framework for a medium to expand her social networks.

The age of onset for tromba possession is typically between eighteen and thirty years, although I did encounter two cases involving girls under fourteen years of age.[5] In addition, different categories of tromba spirits make their debuts at different stages in a medium’s career, so that mediums accumulate more powerful spirits over time. Grandchildren spirits frequently arrive in women who are seventeen to twenty-two, Children arrive most often in women twenty to thirty-two, and Grandparents are almost exclusively seen for the first time in mediums who are thirty-two to forty years of age (again, see figure 7.1).

Boddy’s (1988, 1989) work on zar possession among women in northern Sudan provides clues for understanding gender as a factor in possession experience. She argues that zar is related to concepts of female identity and selfhood and that possession occurs in response to women’s attempts to cope with circumcision and the overwhelming demands associated with adult status: in the Sudan, female “selfhood is…culturally overdetermined” (1988: 16). Even when women have been properly socialized and circumcised, they may still fail to be fertile. As Boddy explains, “When a woman’s fertility mandate is impaired—for whatever reason—her self-image, social position, and ultimately general health are threatened”; it is zar spirits that are “held responsible for procreative mishap” (1989: 186, 188). Within this context it is married and childless women who are most likely to become possessed by zar spirits.

7.1. Table of Mediums. Note: See Appendix A for more details and for descriptions of women who have experienced only possession sickness.

Tromba in Ambanja is likewise associated with female status, but in this case it serves as a confirmation that female status has been achieved. As a woman takes on the role of tromba medium, her identity is transformed in terms of the way it is perceived subjectively and collectively. While in a state of trance, her personality and behavior change in ways that are only limited by the boundaries of her spirit repertoire. Her spirit(s) also impose(s) a new order on her daily life through the complicated categories of taboos that are part of each spirit’s identity and history. Furthermore, as a powerful and respected healer, a medium imposes order on the lives of others: her family, her friends, and her clients are all within her sphere of influence. If she is possessed by a very powerful spirit, then she may affect the actions of living royalty as well. Finally, she joins a special collective of mediums who share the same spirits or who have other spirits from the same genealogies. As will be described below, these women, as spouses to their respective spirits, are redefined in relation to one another as sisters, mothers, and co-wives. Power is inherent to the tromba world, and social integration is also an essential characteristic.

The Cultural Persona: Changing Ethnic Identity

Since it is ancestors that are pivotal in defining Sakalava (and, more generally, Malagasy) identity, it is exclusively through tromba that outsiders may be structurally recognized as Sakalava. Through this process they also gain access to local ancestral power. The significance of tromba in the context of migration is evident in the types of people who experience possession. In the past, tromba possession was exclusively a Sakalava experience; in recent years, non-Sakalava mediums have become involved. They are either settlers or the children of settlers. For these reasons it is not surprising that half of the mediums interviewed during 1987 were themselves migrants, participating in what is viewed as a Sakalava institution. The involvement of migrants in tromba possessionhas occurred through an unusual set of kinship principles that are activated by the spirits. The reasons for this have much to do with local notions of social identity and status and Sakalava conceptions of gender and adulthood.

Migrants as Mediums

Although tromba possession is regarded as a Sakalava institution in Ambanja, the recent proliferation of possession in this town has occurred in part as a result of the active participation of vahiny. As noted earlier, Bemazava royalty especially bemoan the popularity of new and less important Grandchildren spirits, saying that Tsimihety migrants are to blame for bringing them to Ambanja. Nearly all tromba spirits continue to be members of Sakalava royal lineages, either by birth or honorary incorporation (as with Raleva, Raovoay, and their offspring), but tromba mediums are peoples of diverse origins. They include, for example, many Tsimihety, as well as Antakarana, Betsileo, Antaimoro, and métisse. Only Merina are denied the possibility of ever participating, regardless of their personal networks. This is because Merina are taboo to many spirits (they are “fady Merina”). As a result, members of the most powerful ethnic group on a national scale remain among the most peripheral locally in Ambanja. They can never fully participate in tromba, and they are never welcome as members of the Sakalava tera-tany community.

Although I estimate that approximately half of mediums participating in tromba today are of migrant status, they are not short-term (temporary) migrants but settlers or the children of settlers (see figure 7.1 and Appendix A). Drawing again from the sample of twenty mediums (male and female) whom I interviewed in detail, eleven were tera-tany (born locally of a Sakalava mother and father) and nine were vahiny. These vahiny can be broken down into two subgroups: three were settlers (two of whom had Sakalava mothers), and six were the children or grandchildren of migrants (three of whom had Sakalava mothers). All nine were born in the Sambirano. I encountered no short-term (temporary) migrants who had become tromba mediums.

Possession as a means for social integration in Madagascar has been described elsewhere by other authors. Althabe (1969), in his study of possession among the Betsimisaraka of the east coast, has argued that in an area where exogamous virilocal settlement was the rule, possession served as a means to incorporate women into local lineages. Mediumship guaranteed a woman’s participation in her husband’s ancestral lineage, providing her with a way to be involved in local decisions that affected her and her affines. In Ambanja, this incorporating nature of possession has taken one further step. Through tromba, outsiders are incorporated into local Sakalava culture and society. Unlike Althabe’s example, they are not simply affines who are, in a sense, strangers, but more distant non-Sakalava migrants and neighbors. The reason why tromba is so successful in integrating non-kin migrant women is that it operates on kinship-based principles.