| • | • | • |

The Political Basis of Mughal Culture in Bengal

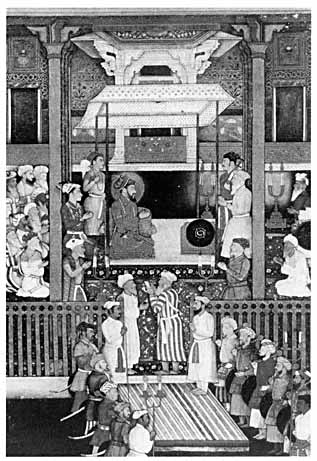

Miniature paintings of the seventeenth-century Mughal court typically depict rows of nobles neatly arranged and ranked by status, their eyes riveted on the raised figure of the seated emperor, while the latter, his head enveloped in a luminous halo, gazes benevolently over the gathered flock (see fig. 18). In our efforts to reconstruct the content of Mughal culture, it is well to consider the model of order and hierarchy evoked in such paintings. For Mughal culture as it evolved over the course of the sixteenth century was above all a courtly and imperial culture, one that, in the manner of those miniature paintings, focused on the person and charisma of the emperor.

Whereas the early Delhi sultans tended to rule as foreigners over a subjugated Indian population, the Mughals, beginning with Akbar (1556–1605), sought to knit North India’s many religious and ethnic communities into a single political system. This policy, which crystallized around 1580 in the wake of the emperor’s abortive experiment in posing as “king of Islam,”[1] inclined the court to an extraordinarily accommodative, even syncretic style of politics.[2] Elaborated by Akbar’s principal ideologue, Abu’l-fazl, the model of imperial authority projected from the Mughal court drew on both Indian and Perso-Islamic notions of kingship. It also drew on a Sasanian Persian model of imperial authority, according to which virtue and order radiated outward and downward from an all-benevolent and semi-divine emperor, supported politically and ideologically by a hierarchically graded corps of soldiers-administrators, the manṣabdārs.[3] While patronizing Islamic institutions as was expected of any premodern Muslim sovereign, Akbar presented himself to his subjects in the radiant glow of an Indian maharaja, appearing in public audience (darbār) seated on a raised platform (jharokhā) in the manner in which traditional Indian kings or images of Hindu deities were presented for public viewing (darśan). As a result, when Indian courtiers gazed upon the seated emperor, they could share a certain double vision, seeing either a pious Muslim sultan or a traditional maharaja tinged with divine power, or both simultaneously.

Splendidly articulated at imperial courts in Delhi, Agra, or Lahore, this hybrid model of political authority was duplicated in miniaturized form in Mughal provinces. In Dhaka, Islam Khan built a scaled-down replica of Jahangir’s imperial court, complete with a jharokhā. Located in the inner garden adjoining the governor’s palace, his jharokhā consisted of a window and enclosed space built on a platform elevated some twelve feet above the ground. Behind the window and raised above those in the garden below, the seated governor received those admitted for private or public audience, or darbār.[4] As a stage for enacting political rituals, the jharokhā thus expressed themes central to Mughal political culture: the subordination of all state servants (i.e., both imperial appointees and Bengali zamīndārs assimilated as imperial jāgīrdārs) to the governor, the corporate solidarity of the ruling class, and the precise position of each member relative to others in the graded hierarchy of state service. Mimicking the court of Jahangir, during formal review, officers would stand before the governor’s jharokhā according to rank, the highest officers situated closest to the jharokhā and the lowest officers furthest from it.[5]

Fig. 18. “Shah Jahan Honors Religious Assembly.” From Stuart Cary Welch, Imperial Mughal Painting (New York: George Braziller, 1978), 102, pl. 31. Reprinted by permission of George Braziller, Inc.

Mughal political culture was also expressed in pervasive categories of thought. From the emperor down to the lowest servant, parties were bound together by mutual obligations articulated through the ideology of “salt” (namak), a semantically rich term expressing notions of protection and dependency that operated simultaneously at social, political, and superhuman levels. Deeply embedded in the culture of the Middle East, this ideology can be traced to the ancient Mesopotamian world, where the Akkadian phrase meaning “to eat the salt of (a person)” expressed the act of making a covenant with a person or of permitting a reconciliation with another individual.[6] The ancient Hebrews considered that they were tied to God by a “covenant of salt,”[7] and that such a covenant legitimized and underwrote earthly kingship.[8] The ancient Persians, too, used the symbolism of salt in the sense of concretizing political covenants—in their case between the emperor and his corps of servants. Officials serving Artaxerxes I (465–425 B.C.) felt obliged to warn their sovereign of possible threats to the collection of imperial revenues, noting that “we eat the salt of the palace and it is not fitting for us to witness the king’s dishonor.”[9] Given these deep historical roots, it is hardly surprising that salt appeared as a metaphor for sociopolitical loyalty and dependence in high Perso-Islamic culture. We find the term used in this sense in the poetry of the Khurasani epic poet Firdausi (d. 1020).[10] From Khurasan, Persianized Turks brought the ideology of salt with them to North India, where in the early fourteenth century it appeared in the poetry of Amir Khusrau (d. 1325).[11]

In Mughal Bengal, the behavior of officers and their subordinates illustrates how thoroughly the ideology of salt had penetrated the ruling class. On one occasion in the early seventeenth century, two rival officers conducted a quarrel through messengers who were dependents of one of these two men. When the messengers were in the company of the other officer, the latter pointed out that their patron had already lost his honor and asked the two why they continued to ally themselves with him. Replied these lowly servants, “We know that our honour has also been lost and will (continue to) be lost; but what can we do? We are under the obligation of his salt.”[12] Here salt is used to convey its most ordinary, metaphorical sense: patrons gave protection to clients, who in turn gave loyalty to patrons.[13]

Within the corps of Mughal officers, salt was understood as a substance either ceremonially or metaphorically accepted and eaten at the hands of the emperor, exactly as in the case of the court of the Persian emperor Artaxerxes I in the fifth century B.C. Binding members of the imperial corps horizontally to one another and vertically to the emperor, the ideology of salt gave expression to corporate solidarity, especially at times when the group felt itself mortally endangered. In 1615, during an imperial invasion of Assam, for example, Mughal troops once found themselves totally surrounded by the army of the Ahom raja. On this occasion the commanding officer and his comrades wrapped their heads in shrouds and, preparing for death rather than surrender, cried out to the Assamese: “As we have taken the salt of Jahangir, we consider martyrdom to be our blessings for both the worlds.”[14]

This usage of the salt metaphor recalls F. W. Buckler’s discussion, in a 1926 essay, of the importance of “rituals of incorporation” in the running of the Mughal political system. The emperor, he wrote,

Within this conceptual framework, ingesting the salt of the emperor communicates the symbolic sharing in the body of the emperor, analogous to the Christian ritual of Communion, in which the believer ritually partakes of and thus shares in the body of Christ.stands for a system of rule of which he is the incarnation, incorporating into his own body, by means of certain symbolical acts, the persons of those who share his rule. They are regarded as being parts of his body, membra corporis regis, and in their district or sphere of activity, they are the King himself—not servants of the King but “friends” or members of the King, just as the eye is the man in the function of sight, and the ear is the realm of hearing.[15]

Finally, Muslims in the imperial corps regarded salt as a substance binding them both to their emperor and to their religion, thereby combining the ancient Persian sense of the “salt of the palace” with the ancient Hebrew sense of God’s “covenant of salt.” In 1612, after defeating the last Afghan chieftain in Bengal to resist Mughal authority, Islam Khan’s men faced the question of how to deal with their defeated Muslim foes. “It was decided,” wrote Mirza Nathan, “to extend hospitality to all the Afghans in the first halting place and to distribute to them the salt of the emperor according to their status: because there was no heavier burden on the neck of a Muslim than the burden of being true to the salt.”[16] Here again clients were bound to their patron—now the emperor himself—by receiving his “salt” in what appears to have been a formal political ritual in which actual salt was distributed and consumed. But in the statement that there was “no heavier burden on the neck of a Muslim than the burden of being true to the salt,” the ideology of salt is transposed to a religious context in which the patron may be understood as God, imposing obligations of loyalty on his community of believers just as the emperor imposed such obligations on his subjects, or as lesser Mughal officers did on their own clients.

Another Mughal ritual of incorporation was the conferral of the imperial cloak (khil‘at) upon a subject or former enemy. Authority, Buckler observes, “was exercised in virtue of this incorporation into the royal person by means of succession established by physical contact through royal clothing. Refusal to acknowledge this transmission of authority, by refusing the robe of honour was an act of independence, that is of treason to the King.”[17] This sort of ritual was dramatically enacted at the dawn of Mughal rule in Bengal, when Daud Karrani submitted to imperial forces in April 1575. Before prostrating himself in the direction of Akbar’s capital at Fatehpur Sikri, the defeated Bengali sultan donned a Mughal sword and an embroidered belt in addition to a cloak of Akbar. All of this symbolized Daud’s incorporation into Akbar’s person as well as Akbar’s empire.

To be sure, as political symbols the jharokhā, salt, and the khil‘at were already present in pre-Mughal Bengal. Both Chinese and Portuguese travelers to the Bengal capital had described raised platforms on which the sultan sat and reviewed his officials in a manner not unlike Governor Islam Khan Chishti in his Dhaka darbār. And we have noted the political usage of salt in the poetry of Firdausi and Amir Khusrau. Presumably, the early governors and sultans of Bengal carried into the delta the same notions of statecraft and political legitimacy that had informed their Persianized Turkish forebears in Khurasan and North India, including the ideology of salt. Finally, the political use of the royal cloak, or khil‘at, was also known to the Bengal sultans. In the course of an interview with a Portuguese mission in 1521, Sultan Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah embraced the European captain, laughed, and promised him favors. “Then,” narrated the European interpreter, “he turned to me and ordered that I be given a robe that he had worn.”[18]

But in other respects Mughal political culture in Bengal can be sharply distinguished from that of the sultanate. Down to the end of the sixteenth century, the Mughal ruling class had been predominantly non-Indian. In 1595, 61 percent of Akbar’s nobility were ethnic Iranians or Turks, of whom the vast majority had migrated directly from Iran or Central Asia. During the seventeenth century, however, the empire’s foreign character steadily diminished. By the end of that century, just over a third of the nobility were of known Iranian or Turkish ancestry, and fewer than a quarter of these were foreign-born immigrants.[19] Already by Jahangir’s reign there had emerged in the imperial corps an important and growing section of Muslims who, while claiming a paternal ancestry beyond the Khyber, had been born in India of Indian mothers. These persons not only spoke a form of vernacular Hindi-Urdu as their “mother tongue”; they also carried with them deeply held assumptions about life and death that for several centuries had been nurtured in North India within the matrix of Rajput culture.

Thus, for example, when the Mughal governor Qasim Khan faced imminent defeat in a bitterly fought battle near Dhaka in 1617, he personally beheaded his chief wives, after which many of his comrades similarly performed the rites of murdering their own families in one another’s presence.[20] The practice of jūhar, or the destruction of women and children as an alternative to suffering them to be captured by enemy forces, was a Rajput rite assimilated into imperial culture through Akbar’s policy of incorporating Rajputs into the Mughal corps and the inclusion of Rajput women in the Mughal harem. Now it was carried into Bengal. Similarly, too, Mughal officials in Bengal preferred Ayurvedic, or native Indian, medical theory over the Yunani, or Greek (“Yunani” is a corruption of “Ionian”), medical system inherited by classical Islamic civilization. The ailing Islam Khan, himself an Indian Muslim, requested an Indian physician when he neared death. There not being one available, the governor only reluctantly accepted a Muslim ḥakīm, who was later blamed for having administered the wrong treatment and unnecessarily killing him.[21] When the governor of Bihar suffered from an illness that paralyzed half his body, the Emperor Jahangir sent him two Indian physicians from amongst his personal staff.[22] And when illness seized Mirza Nathan, the officer’s advisors sent for a practitioner of Ayurvedic medicine (kabirāj) who successfully treated him by consulting the appropriate astrological signs and having him drink a poisonous drug mixed with lemon juice and ginger.[23] Such reliance on Indian systems of medical therapy in the face of fatal illness and on Rajput customs when faced with immanent annihilation in battle—both of them life-threatening situations—suggests how thoroughly Indian values had penetrated Mughal culture by the early seventeenth century.