| • | • | • |

Late Fourteenth-Century Latinate Jewish Wills

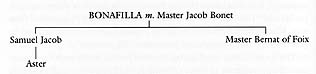

Bonafília or Bonafilla, “wife of Master Jacob Bonet,” in her testament of 18 January 1370 at Puigcerdá appoints as her executors Master Boniac Abraham and Yitzhak Astruc (“Itzah Struch”). “Master” here is ambiguous but probably indicates status in the aristocracy of the ḥakīm class as savant-physician. Besides burial in the Jewish cemetery, Bonafilla leaves 10 sous for oil for the lamps of the synagogue (scola) and “10 in alms for the Jewish quarter [call] of Puigcerdá.” One son, Master Bernat of Foix, receives 5 sous; the other, Samuel Jacob, gets 5 sous plus an immediate payment of 50 pounds.[4]

The name Bernat in a Catalan-Occitan Jewish family seems unprecedented and suggests an error of some kind. The careful index by Yom Tov Assis for the catalog by Régné, covering nearly 3,500 charters about Jews for over a hundred years (1213–1327) of Arago-Catalan crown registers, does not turn up a single Jew named Bernat; even the short index of converts to Christianity has none. Among Catalan Christians the name was very popular; a first-name index for the documents of Jaume the Conqueror lists over 150 Bernats plus nearly 70 more in abbreviated form. Of Germanic origin, the name has none of the equivalence value of a name such as Benet (“Benedictus”), paralleling Hebrew Baruch or the then popular Berachya. Was this Bernat a convert? It is highly improbable that an apostate son could have appeared in a public Jewish will at this period. Could the scribe have intended the Catalan name Bonat, common to Jews and Christians then?

Paleographically, all letters of this name in the will are clearly present in Romance form, except for the first e, which an overstroke indicates: BRNAT. Since Bonat/Bonanat has a deformation or variation as Brunat, Boronat, and Bornat, such readings of the name would solve the puzzle. It is not necessary to fall back on that analysis, however, since Seror has found a Jewish Bernart and a Benaart in Paris and a Bernardus in Marseilles while compiling his lexicon of medieval French Jewish names. The dates of appearance of these names are instructive—respectively 1291, 1292, and 1351—as they are relatively late and therefore suggest the acculturative pressures then increasing. Since Jews of this time and place took various kinds of nonreligious names, including many popular also among their Christian neighbors, perhaps we ought not to cavil at “Bernard.” But the name does fall outside almost all contemporary patterns for Jews in the realms and invites in its family context a strong suspicion of undue influence from and deformation by the surrounding Christian culture.[5]

In this testament, 20 sous go to Joia, daughter of Samuel (ben) Abraham Cohen (Joi, like Goig, is Catalan for “joy”). Everything else, movables and real property, goes to Samuel Jacob’s daughter Aster, granddaughter of Bonafilla. All seven witnesses are Christians. All money is in Barcelonan sous. All the principals are Jews of Puigcerdá. The family structure is

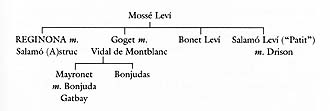

Ten years later, on 24 March 1388, Regina or Reginona drew up her will at Inca on Majorca island.[6] She was the daughter of Mossé Leví and the wife of a tailor of Inca named Salamó (A)struc. Gravely ill but with faculties intact, she declares her husband both executor and universal heir. Her first concern is that all her debts and obligations be met from the estate “without legal form or fuss.” She wishes to be buried in the Jewish cemetery at Inca “before the grave of my said father,” with suitable ostentation: “well and elegantly [and] according to Jewish custom.” Reginona’s sister Goget, wife of Vidal de Montblanc of Majorca, receives 3 pounds “to buy clothing for mourning.” Twenty sous each go to Goget’s son Bonjudas (“Boniuetes”) and her daughter Mayronet, the wife of Bonjuda (“Beniuha Gatbay”). Twenty more apiece go to Reginona’s brother Bonet Leví, to another brother Salamó Leví “alias Patit,” and to the latter’s wife Drison. Reginona also gives 10 sous, “for the love of God,” to buy oil to burn “in the lamps of the synagogue.” Six witnesses sign, with the notary doubling as a seventh witness; all six seem to be Jews.

Several new names occur. Reginona is simply a diminutive or intensifier of Regina, as Meironet (“Mayronet”) is of Hebrew Meir. Beniuha and Boniuetes are variants of Bonjuda(s), bon slipping into ben. Patit is Catalan Petit, for the Hebrew name Katan (“small”); it is also a Catalan Christian lineage. Three names pose a challenge. Goget seems to be a diminutive of Goig in its variant Gog; Drison may relate to the Occitan name Treysona, cited by Seror only once, at Manosque. The masculine surname Gatbay, despite its intrusive t not untypical in Catalan, is the common Jewish surname Gabbai, with an Aramaic etymology as tax collector or as synogogue functionary. The immediate family, in order of appearance, is small:

Ten years later Jacob Boniac drew up his will at Puigcerdá. Dated April 1398, it leaves a series of small legacies to friends and relatives, including 30 sous for one grandson and 20 to another, 20 sous “to my relative or cousin Ana Goya,” 10 to her son, and dowries of 40 sous for each of the daughters of his great grandson Deglossal (Deulosal) Vidal. He returns a dowry of 40 Barcelonan pounds to his wife Marcona and names her universal heir for the bulk of his possessions. For charity he leaves 5½ sous for “the abashed poor,” and “all my clothing to my poor relations at the discretion of my executors.” Clothing in the Middle Ages was often valuable and cherished, handed down through several generations. Two pieces here are held out for favorite relatives. Twenty sous are set aside as a fund for oil, to be burned “in the synagogue of the Jews of the said town to honor God,” at the rate of 5 sous yearly over four years. The seven witnesses include Guillem Gueca taverner and two Jews, Samuel ben Abraham Cohen and Bondit ben Samuel Cohen. In his codicil of 30 February 1401 he selects as executor “Master Meir Bonet physician,” a Jew of Perpignan. The witnesses are divided under the rubrics “Christians” and “Jews,” the latter comprising the physician Bonet, Deglossal Vidal, and Jacob Cohen. New names here are Catalan Anna from Hebrew Chana/Ana, Marcona as feminine diminutive of Catalan Marc, and Bondit as the past participle of Catalan dir in the sense of “well said,” unless it is variant here for Bendit (“blessed,” for Hebrew Barukh).[7]

Three years later the wills continue. Vidal Bonafos senior (pater), for example, a Jew of Perpignan taken ill at Puigcerdá, drew up a long will on 27 February 1401, adding a codicil on August 31.[8] The codicil expands his largesse by giving 2 sous apiece to those assisting him in his last illness. A number of money gifts, some in florins, include: “I leave [money for] a lamp which is to burn in the synagogue or scola.” But all such post–Black Death wills mirror a different society, both Christian and Jewish. They are not so precious as the early models.