| • | • | • |

Knowing the City: The Bureau d’Hygìene

Perhaps the most long-lasting and widely imitated of Siegfried’s social reforms was the Bureau d’hygiène, France’s first municipal health department, created in 1879. After 1902, every French city of more than twenty thousand inhabitants was required by law to establish a health bureau modeled on that of Le Havre; its pathbreaking work earned it national and international acclaim among doctors, hygienists, and politicians. As a precursor and, later, outpost of the War on Tuberculosis, the Bureau d’hygiène attempted to translate the medical and hygienic knowledge of the dominant etiology into local knowledge and to track the disease administratively through the city and through the years.

Along with Siegfried, the person most responsible for the establishment of the Bureau d’hygiène was Joseph Gibert, a Swiss-born physician who settled in Le Havre after attending medical school in Paris. Gibert is known to some historians of France as a principled convert to the cause of revisionism in the Dreyfus case; the doctor interceded with his friend and fellow Havrais Félix Faure, president of the republic, and was shocked and dismayed when Faure admitted that Dreyfus had been convicted based on secret “evidence” but invoked raison d’état in refusing to reopen the case.[45] But Gibert spent most of his career, outside of his private practice, seeking ways to improve the desperate sanitary situation of his adopted city. In 1878, the first year of Siegfried’s tenure as mayor of Le Havre, the two friends first put the idea of a municipal health department before the city council, on which Gibert also served. The doctor spoke eloquently about the need to preserve the country’s human resources, a need that was especially acute in light of the country’s demographic and political decline as a world power. “If we are not first [among nations] in the production of human life”—a reference to the country’s falling birthrate—“let us strive to be first in the saving and husbanding of this incomparable treasure, and preserve it, through a practical and serious organization of public hygiene, from the scourges that constantly threaten it.” Gibert told the council members that the nation would applaud Le Havre’s initiative “if every year more healthy and robust defenders are saved for its battalions, more hands are saved for its workshops, [and] more young girls are prepared by a salutary education for their role as mothers.”[46] From the very beginning, then, concerns over national decline, military might, productivity, and parenthood conditioned the fight against tuberculosis and other causes of death, on the local as well as the national level.

Although several members of the city council suggested modifications to Gibert’s and Siegfried’s proposal to reduce its cost, the only real opposition to the plan came from Louis Brindeau. (Twenty-four years later, as mayor, Brindeau would praise the bureau and its work in glowing terms.) The councilman objected that the creation of a new city department would entail excessive expenses. Mayor Siegfried intervened to suggest to the council some specific benefits the bureau would bring. It would monitor, he said, the day-to-day sanitary topography of the city. “Thanks to the reports of the Bureau d’hygiène, it will be possible to compile a synoptic map of the progress and intensity of diseases in [our] neighborhoods.” Gibert concurred that only through detailed knowledge, by mapping the incidence of diseases such as tuberculosis in the city’s streets and neighborhoods, could science determine their true causes. Brindeau insisted that “to create a special office of hygiene is to spend a great deal [of money]…for statistical information.” He suggested instead that the same amount of money be spent on sewers, public baths, and other material sanitary improvements, while existing commissions and departments could compile all necessary statistics without the additional expense.[47]

Brindeau could not stem the positivist tide, however, and the reformers’ arguments regarding the need to collect more comprehensive and systematic information won the day. Le Havre inaugurated its new Bureau d’hygiène in 1879 and began an era of exactly what Lecadre had called for: “incessant observation.” The bureau was given authority and responsibility over all health-related matters, and its day-to-day functions included maintaining France’s first casier sanitaire, a record of the place, time, and cause of every death in the city, as well as keeping track of births; disinfecting the lodgings and personal effects of victims of contagious diseases (including tuberculosis); inspecting samples of foods and beverages for quality; administering smallpox vaccinations; following up complaints concerning various causes of insalubrity; inspecting schools, other public facilities, and industrial establishments; and surveillance of registered prostitutes for venereal diseases.[48]

Right from the start, the bureau was forced to come to grips with tuberculosis, the city’s leading killer. During the 1880s, its periodic reports gradually elaborated all three elements of what would later become the dominant etiology of the disease (contagion, housing, and immorality), while at the same time the major French medical journals and the professors at the Paris faculté were only taking the first tentative steps toward the same ultimate conclusion. The bureau’s very first report, on its operations in the first three months of 1880, placed great emphasis on tuberculosis, pointing out that no epidemic or any other cause ever approached it in the number of deaths it accounted for. This early report, marking a sober realization of the difficult tasks facing the bureau, singled out two particularly pernicious causes of tuberculosis. Though it mentioned heredity, contagion (two years before Koch), poor nutrition, and lack of ventilation as contributory factors, the report denounced above all “venereal excesses among adolescents and alcoholic excesses,” often found doing their damage together in the same person. Four years later, in 1884, the bureau’s director, Dr. A. Launay, lamented in a brief passage on tuberculosis that “alcoholism continues its ravages” and otherwise shed no new light on the matter.[49] In Le Havre, one of the most “alcoholic” cities in France,[50] the moral etiology of tuberculosis took hold quite early.

By 1887, five years after Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus, as most of the medical profession was slowly being won over to the contagionist perspective on tuberculosis, the view from Le Havre had further evolved in the direction of what would become the dominant etiology. Doctor Gibert, in summarizing the epidemiological evidence gathered by the Bureau d’hygiène, cast the decades-old concern over slums and overcrowding in the new light of contagion. “There is a constant relationship,” he wrote, “between…population density and pulmonary phthisis.” To illustrate his point, he compared the figure of 1 tuberculosis death per thousand population in the cités ouvrières to 5 per thousand in Notre-Dame and Saint-François. (Reformers preferred this particular comparison to strict neighborhood-to-neighborhood ratios, because it purported to encompass socially identical populations in different environments.) While allowing that “we must admit the influence of contagion,” which had been scientifically proven, Gibert could not yet bring himself to abandon completely some older miasmatist notions, as in this equivocal statement: “Overcrowding, whose importance is so great in Le Havre, acts no doubt through the vitiation of the air, but also…through contagion.” The moral etiology, too, had progressed in terms of sophistication and statistical certainty; here Gibert contended that “alcoholism, by weakening the individual who indulges in it, prepares the way for contagion, and this can explain the enormous number of consumptives in Le Havre.” It was not until roughly ten years later that this formulation became the widely accepted dogma of official French medicine. Interestingly, this 1887 report is one of the extremely rare official documents from Le Havre to actually make reference to the city’s standing as tuberculosis capital of France and probably all of Europe. In partial explanation of that status, Gibert also claimed that Le Havre “appears to be the European city where the most alcoholic beverages are consumed.” For the most part, local officials preferred not to call attention to the city’s unenviable standing, while still insisting on the need for public health reform.[51]

Ten years after the bureau’s creation, the new etiology of tuberculosis had taken hold in Le Havre, and the local manifestations of contact with bacilli, substandard housing, and immoderation assumed preeminent importance in the bureau’s reports. The degree of emphasis accorded to any individual factor varied with local circumstances; for example, in 1890, the bureau’s advisory committee made the bold claim that the true causes of tuberculosis were only known (and knowable) thanks to the establishment of the bureau itself. “Nobody knew, before the creation of the bureau, what its topographical distribution was. Today…it is easy to know the true causes of its propagation.” The meticulous mapping of every death from tuberculosis revealed that its primary cause was overcrowding (which facilitated contagion), since mortality was highest in the most densely populated districts of the city. When commenting on the sexual distribution of the disease, the bureau invoked alcoholism to explain the significantly higher incidence among men than among women.[52]

Several points that went unacknowledged throughout the history of the bureau’s work on tuberculosis should be addressed here. The advisory committee’s assertion notwithstanding, observers such as Lecadre had linked the disease to overcrowding and housing conditions long before the creation of the Bureau d’hygiène, although without framing the issue in the language of contagion. Moreover, by deciding to investigate tuberculosis geographically, that is, by using the casier sanitaire data to represent its incidence spatially through the streets and neighborhoods of the city, the bureau predetermined the outcome of its inquiries. Had similar records been kept regarding differential tuberculosis mortality by occupation, wage level, place of birth, or any other variable, different conclusions certainly would have been reached. However, given the novelty of Le Havre’s Bureau d’hygiène, even in 1890 the advisory committee may have felt the need to justify its continued existence and rightful place in the municipal administration. It had to claim that important progress was being made, if not in material changes at street level, then in the realm of local knowledge.

Similar claims of progress continued into the 1890s and beyond, despite occasional administrative difficulties and Le Havre’s persistently high death rate from tuberculosis. A shortage of office staff forced the bureau to suspend the maintenance of the casier sanitaire in 1893; it was not until mid-1901 that temporary outside assistance brought the records fully up to date, whereupon they lapsed again for at least nine more years.[53] “Little by little, we are making progress,” Gibert reported in 1897, “but it is still not enough.” Other officials shared his optimism but not his caution; shortly after taking office in 1908, with Le Havre still ranking consistently at or near the top among French cities in both tuberculosis mortality and overall mortality, Mayor Henri Genestal confidently proclaimed, “The state of public health in our city is excellent.”[54]

Throughout its early years, the Bureau d’hygiène attempted to preach the antituberculosis gospel of prudence and cleanliness to the population of Le Havre. Its functions included supervising the municipal disinfection service, a service for which the bureau constantly strove to incite demand. Gibert was “pleased to report” to the advisory committee in 1896 that “the population is taking up the habit of having their lodgings disinfected after deaths from pulmonary tuberculosis.” He urged his fellow doctors to encourage this practice further, until the time when all tuberculosis deaths would be followed by disinfection as a matter of course. At the same meeting, other members of the committee pursued Gibert’s line of reasoning and called for mandatory declaration of all diagnosed cases of tuberculosis. Declaration to local authorities was already required by law for several other contagious diseases and would have facilitated universal disinfection. While one doctor called for mandatory declaration along with the isolation of tuberculosis cases within hospitals and the distribution of spittoons and anticontagion instructions to all those afflicted with the disease, another committee member demurred. Any measure that singled out tuberculosis victims, he argued, would rob them of hope. Many patients who showed signs of the disease had been carefully shielded from that fact by their physicians, and so strong was the popular association of tuberculosis with despair and death that to reveal the truth would shatter their illusions of possible recovery and a normal life.[55] These were precisely the same dilemmas and controversies that the entire French medical profession was facing—although the critical mass of activist doctors and social reformers in Le Havre seems to have caused the issues to appear there several years earlier than elsewhere in France—and despite the energy and money spent, the Havrais came up with no unique or original practical solutions to the problem of tuberculosis. In the domains of administrative surveillance and statistical knowledge of the disease, however, as in mortality, Le Havre far outdistanced all other French cities and the central government as well.

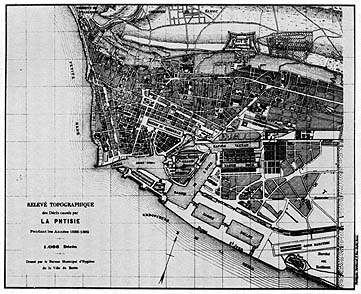

The health department’s crowning achievements in this regard were its two published decennial reports, the first covering the 1880s (published in 1893) and the second the 1890s (published in 1903). Prosaically entitled Relevé général de la statistique démographique et médicale, each was a prodigious accomplishment, an encyclopedic monument to the statistical quadrillage of a city and its population. For example, each volume contained detailed foldout maps of Le Havre; each map was marked with a pattern of dots, each dot representing a death from tuberculosis, for the years covered in that volume. (See fig. 11.) Together, the maps testify not only to the bureau’s thoroughness in collecting data but also to its leaders’ passionate commitment to medical topography as a means of fighting disease. Such maps of disease incidence, also known as “spot maps” or “dot maps,” were not new in the 1880s. Epidemics of yellow fever and cholera had previously given rise to case mapping in various British and American cities. But Le Havre’s tuberculosis maps of the late nineteenth century signaled a shift in the object of mapping from the exotic, exogenous, and epidemic to the familiar and endemic.[56]

11. Spot map showing deaths from tuberculosis in Le Havre, 1888-1889. From Relevé général de la statistique démographique et médicale, 1880-1889.

Mayor Brindeau wrote the preface to the first decennial report in 1893. As a city councilman fourteen years before, Brindeau had been the lone voice in opposition to the establishment of the Bureau d’hygiène. In his lengthy preface, he recalled that the proposal had “encountered a fairly intense opposition.” “Some keen minds contested the usefulness of an institution whose organization, costly as it was, would only produce…statistics which were quite interesting from a scientific point of view, to be sure, but would bring no practical result.” Without ever admitting that these were precisely his own objections (or that he was the only member of the city council to voice them at the time), Brindeau suggested that the experience of fourteen years had shown them to be well intentioned but unjustified. The wisdom and diplomacy of the bureau’s collaborators, he wrote, had succeeded in convincing private interests—here he was presumably referring to the proprietors of factories and plants classified as unsanitary establishments—to conform their practices to the principles of public hygiene, even though the bureau lacked the legal authority to enforce its policies. Brindeau further pointed to a two-thirds decline in diphtheria deaths since the bureau began its disinfection service in 1885 as evidence that the office had had a positive practical impact. Yet notwithstanding his earlier skepticism regarding the utility of statistics, even Brindeau had to admit that the bureau’s statistical work, as summarized in the decennial volume, was the pride of its brief history. In approving the publication of the volume, he pointed out, the city council had agreed to use it as the basis for considering sanitary improvements. “We can therefore say that the cleaning up of Le Havre will be the practical conclusion, so to speak,” of the bureau’s massive statistical compilations.[57] This was the great and largely unfulfilled promise of the Bureau d’hygiène. In the end, even the most sophisticated statistics could not raise money, expropriate a slumlord, or house and feed a day laborer and his family.

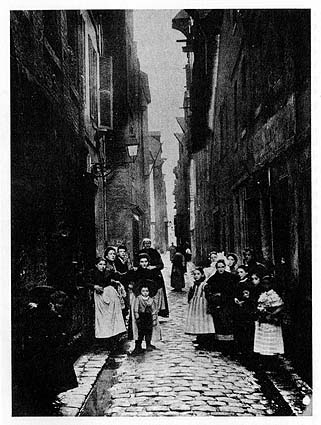

12. Rue du Petit Croissant, a street that perennially accounted for many tuberculosis deaths in Le Havre, ca. 1900. Photo courtesy of Jean Legoy, Le Havre.

As far as tuberculosis was concerned, the body of the two decennial reports was concerned with elaborating the street-by-street, house-by-house understanding of the disease, in which all components of the dominant etiology took their place. In the chapter of the 1880–1889 volume entitled Mortality by Street, recognizing that poverty, poor housing, and disease often went hand in hand, Doctor A. Lausiès questioned the true role of poverty in determining mortality. “If poverty [la misère] means a shortage of the material things in life and entails a lowered resistance to causes of death, it is difficult to appreciate the part played by those too-often concomitant phenomena, ignorance and vice.” To untangle the web of factors, Lausiès called attention to the seven streets at the top of the mortality list.

The tragedy of poverty seems to have been altered in its moral status, in the view of Lausiès, when ignorance and vice were also present, as in the rue des Boucheries. “More than anywhere, it seems that the residents, deprived of air, sunlight, and cleanliness in this narrow street, wallow in their misery and abandon themselves with a kind of fatalism to the inability of ever getting out.”[59] In other words, Lausiès hinted, economic poverty is one thing; but the moral defects of the rue des Boucheries population made them truly different, much as the unsanitary housing commission perceived some slum dwellers as a race apart.Without a doubt, poverty is extreme in all of them, but they suggest some quite different [nuances]. The rue de la Vallée is full of Bretons, poor for the most part, whose passion for alcohol is well known; the rue d’Albanie has never evoked images of a comfortable life; as for the rue des Boucheries, it brings together all the causes of insalubrity. The social milieu is perhaps poorer there than anywhere else, and ignorance plays a role there along with alcohol.[58]

Elsewhere in the 1880–1889 report, Doctor Gibert stressed a different theme within the dominant etiology, momentarily downplaying specifically local factors. “What dominates the entire question of phthisis, in Le Havre as in London and Paris and in all human agglomerations, is contagion and nothing but contagion.” Gibert called for a single “social remedy” to combat contagion and eliminate tuberculosis: housing reform. The cités ouvrières should be multiplied, he wrote, and spacious, well-built workers’ apartments should be constructed on the outskirts of the city, so that “air could circulate freely, and so that contagion from house to house could be avoided.”[60] In this one volume, then, in 1893, a fully elaborated version of the dominant etiology was put forward in Le Havre, well before its diverse elements were assembled in coherent form elsewhere.

By the time the second decennial report (covering the years 1890–1899) was published in 1903, there appears to have been a subtle shift in the attitudes of the city government and the Bureau d’hygiène toward health and mortality. In his preface, Mayor Marais struck a defensive posture from the start. “The city of Le Havre has never been unhealthy [and] is making progress in terms of salubrity, [while] new improvements must be pursued and will be obtained.” Marais obviously felt the need to contradict a certain perception of his city, whether through specific criticisms from the outside or simply a general image of Le Havre as diseased and unclean. In his discussion of the bureau’s statistics, he proudly noted a decline in overall mortality from the 1880s to the 1890s of 30.9 to 29.7 per thousand per year.

The claim that Le Havre’s high mortality was due in large part to nonresidents who transited through the port or otherwise found themselves in the city when they died (of illnesses contracted elsewhere) dates back at least as far as the reports of Adolphe Lecadre; however, it came to be asserted with greater frequency and insistence in the first decade of the twentieth century.A proportion still too great, certainly, whose significance must be attenuated to some extent by the contribution of the transient population [le contingent fourni par la population flottante], but which justifies in any case our continuous search for improvement.[61]

Later in the same volume, the bureau’s director, Dr. Henri Pottevin, sought further explanations for Le Havre’s death rate—from tuberculosis in particular—that might absolve the city’s health policy of blame, or at least mitigate its responsibility. Other cities such as Paris “exported” their tuberculosis patients, Pottevin contended, either to the suburbs or to family members in the provinces. Because these former Parisians died outside the city limits, their deaths were not included in the capital’s statistics, thereby artificially depressing its mortality figures. In contrast, “Le Havre keeps all of its tuberculeux,” Pottevin explained, “and therein lies one of the primary causes of our [high] tuberculosis mortality.” He pointed to “the predominance of the poor element” in the city’s population as an additional reason for the misleadingly high statistics, along with the fact that most Havrais were of Norman or Breton origin. Since nationwide, these were “the French races most heavily afflicted” with tuberculosis, Le Havre’s high rate was understandable.[62]

All of these protestations seem intended to explain away or make excuses for the city’s continually high mortality figures. They are also part of a broader pattern that goes beyond the interpretation of statistics. Local officials consistently downplayed both the role of material well-being in the incidence of tuberculosis and the need for remedial material action to fight it. In the same report, Pottevin reviewed a wide array of strategies recommended by various medical authorities—from sanatoriums to wage increases for workers—only to conclude that “the essential part of the antituberculosis program, and perhaps the only one in which our immediate action can be effective, is the work of social education.” Teaching the poor not to spit on the ground, to have their lodgings disinfected, and in general to avoid infecting those around them when they became sick—this was the bureau’s crucial duty in the War on Tuberculosis.[63] If the welter of social factors that contributed to the spread of disease could be distilled for the most part into a matter of personal negligence, the failure of the state or private philanthropy to commit substantial resources to the battle would be to some extent justified.

The hypersensitivity of Havrais officials to their city’s death rate continued through the years preceding World War I. In 1911, for example, Dr. Adrien Loir (then director of the Bureau d’hygiène) went to great lengths to explain away the overall mortality figure from the previous year. In the bureau’s annual report, Loir explained that several circumstances beyond the administration’s control inflated the numbers for Le Havre, especially in comparison to other cities. “Our mortality statistics in Le Havre are augmented by three important causes”: (1) counting residents of suburban towns who died in the city’s hospitals as part of Le Havre’s total deaths; (2) a peculiarity of major ports, the influx into the city of would-be emigrants from the “interior,” who took up temporary residence in Le Havre pending departure only to fall ill and die in its hospitals; and (3) assigning to Le Havre the deaths of foreigners who drowned in the port area, who disembarked from ships already ill, or who died aboard ship less than two days before arrival in Le Havre.[64]

Although many cities made similar claims about being unfairly burdened in official statistics with deaths that rightly belonged to other jurisdictions, there may well have been some truth to Loir’s contentions. Nevertheless, the insistence of city officials in pressing these claims and the variety of excuses invoked suggest that other factors were at work in these years. For one thing, a national public health law passed in 1902 not only required all cities to establish health offices modeled on that of Le Havre but also mandated special inquiries and remedial measures for those cities that exceeded the national average in mortality for three years in a row.[65] Furthermore, health statistics (including overall mortality and tuberculosis mortality) for all major French cities had been compiled and published by the Ministry of the Interior only since the late 1880s; this Statistique sanitaire des villes de France for the first time allowed cities to be compared in matters of health and disease. In Le Havre, the defensive attitude surfaced especially in the decennial report covering the 1890s. The compilation of the report coincided with a period of intense public discussion and debate concerning public health—and tuberculosis in particular—with governmental commissions investigating various problems and possible reforms and with parliament debating at great length the public health law finally passed in 1902. If ever Le Havre’s status as tuberculosis capital of France were exposed to public view, this was the time.

In fact, the fate of the 1902 public health law parallels the course of antituberculosis efforts in Le Havre and of the French War on Tuberculosis as a whole. The law seemed to pursue an aggressive strategy in the area of information gathering and surveillance alongside a cautious approach to material intervention. Its principal provisions included the establishment of bureaux d’hygiène, the mandatory declaration by physicians to local authorities of all cases of certain contagious diseases (tuberculosis was not among them), and requiring special investigations whenever a city’s mortality rate consistently exceeded the national average.[66] In a circular to departmental prefects in 1907 concerning the application of the law, Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau insisted that one of the chief roles of government in public health matters was as “propagandist” and “apostle,” educating the population to ease the acceptance of hygienic ideas and practices.[67] Moreover, several years after its passage, the nation’s public health authorities agreed that the law was rarely enforced and that without enforcement, it could have little effect. Even the new bureaux d’hygiène created by the 1902 law remained nothing more than “phantom boards” and accomplished very little, some hygienists complained.[68] In Le Havre, where the health board was much more than a mere phantom, the enforcement of public health regulations was still no sure thing, ranging from vigorous to half-hearted.