| • | • | • |

Response: Diana Delia

Alan Samuel has sensibly argued that the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship is connected with the way in which Egypt was administered. He has challenged the traditional claim that the Ptolemies absolutely dominated a tightly knit, rationally organized state. His conclusion that they did not is significant—not only for our understanding of the administration of Ptolemaic Egypt per se but because it inspires reappraisal of basic presuppositions about the interrelationship of monarchy and bureaucracy in practice and in theory.

At a symposium on Hellenistic history and culture, the Hellenocentric thrust of Professor Samuel's paper is, of course, appropriate. As a social historian of Greek and Roman Egypt, I nevertheless feel some concern. It is clear that the Ptolemies retained the traditional administrative nome divisions of Egypt and that the office of nomarch continued, although by the second half of the third century B.C. nomarchs would relinquish military and many other powers to the newly imposed nome officials known as strategoi.[1] Ptolemaic papyri attest to state monopolization of the cultivation and manufacture of papyrus, oil, and textiles, state control of the production of salt, and close supervision of quarries and mines. Other documents indicate that the cultivation of grain was controlled by means of state distribution of seed, in return for which farmers were required to pay a portion of their harvests. These subjects have been addressed in the prolific economic studies of M. I. Rostovtzeff and Claire Préaux as well as by other scholars.[2]P. Rev. Laws, dating to 259 B.C., further demonstrates that money taxes were levied on other manufactured goods and agricultural products as well.[3]P. Tebt. 703, dating to the late third century B.C., discloses the minute attention paid to all potential sources of revenue, including enumeration of livestock and the inspection of sown fields and weaving houses to assess productivity and to guard against peculation. Nevertheless, the intense interest of the Egyptian state in revenue matters did not spring full-grown out of the head of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in the manner of Athena, but instead ought to be understood as a continuation of pharaonic practice.[4] For example, the Palermo stone indicates that a biennial census of cattle took place as early as the Old Kingdom.[5] Middle and New Kingdom documents attest to an elaborate system of taxes and show that land was resurveyed after the annual Nile inundation to determine the liability of Egyptian peasants to pay a portion of their harvest to Pharaoh, as they later would to Ptolemy.[6] Moreover, royal officials regularly supervised expeditions to Egyptian quarries and mines.[7] The elaborate instructions imparted to royal viziers, especially Rekhmire, suggest that they carried out the functions which the Ptolemies would later apportion among their dioecetes,nome strategoi, and chrematistai.[8] Hence, as the Ptolemies indeed retained or adapted pharaonic administrative institutions,[9] it follows that their ideology of kingship to some extent also derives from pharaonic prototypes.

In response to Rostovtzeff's grand view that the Ptolemaic administration was more refined, more logical, more comprehensive, more, shall we say, quintessentially “Hellenic” than its pharaonic antecedents,[10] Professor Samuel now posits the claim that the Ptolemaic bureaucracy was not rationally ordered, that it was not planned, and that it developed on an ad hoc and piecemeal basis as specific needs arose and former methods, proving to be inadequate, were abandoned. He raised a similar suggestion some twenty years ago in connection with his seminal study of the nomarch's bureau in the third century B.C.[11]

The lack of distinction that existed between public and private activity has also been duly emphasized by Professor Samuel. To be sure, the Zenon archives demonstrate Apollonius' use of official authority to attain private ends and the deployment of his private resources to accomplish official tasks.[12] Nevertheless, as Dorothy Crawford has pointed out, since Ptolemaic officials appear to have received no regular salaries, this lack of distinction between public and private spheres of interest promoted corruption, as administrators abused their official positions in order to line their own pockets.[13] Reiterated exhortations to royal officials to be fair and just suggest that, although quite the contrary state of affairs frequently prevailed in fact, excessive exploitation was nonetheless condemned in principle as abusive.[14] As Hermann Bengtson aptly observed, every administration is only as good as the men who comprise it.[15]

What is most exciting is the way in which Professor Samuel links these two bold theories, arguing that administrative activity, far from being the coherent result of royal planning, was rather the aggregate of activities of exploitative officials, and that what has traditionally been touted as a system of administrative checks and balances actually represents “a desperate attempt on the part of the crown to get some control over a structure which, on the lowest village levels, was practically autonomous.” Hence the king, according to this theory, existed alongside the administrative bureaucracy, intervening only to check abuses or to curb the rapacity of his administrators. At the same time, however, I wish to point out that a symbiotic relationship continued between the two, since the king depended on his administrators to collect the revenue that he used for military and personal ends, and the administrators ultimately owed their appointments to the king; these selfish considerations, on occasion, surely reconciled the tension and conflict between royal and administrative objectives. Moreover, at least one pharaonic precedent for the discordant state of affairs that Professor Samuel has described comes to mind: the New Kingdom edict of Horemheb, which outlines the measures that this king intended to pursue to check the flagrant corruption of fiscal and other administrators similarly abusing their positions for personal gain.[16]

In keeping with Professor Samuel's premise that the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship was intimately connected with the way in which Egypt was administered, let us turn to some of the aspects of royal ideology mentioned by him.[17] The first of these is that, from the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus on, the king was worshipped as a god. This claim, while on the surface appearing to be “minimalist,” initially troubled me in view of the proverbial skepticism harbored by certain Greek intellectuals concerning the divinity of any living monarch. One need only recall Demosthenes' scathing response to the motion to deify Alexander at Athens: “Let him be a son of Zeus and Poseidon also, if he wishes” [18] or the Cynic Diogenes' provocative rejoinder, “Then make me Sarapis!” [19] Even if these anecdotes are totally apocryphal, they nonetheless reveal a certain resistance among Greek intellectuals to the substitution of theos for basileus.[20] As C. Bradford Welles succinctly observed, “no Greek, ancient or modern, ever thought that anyone was really superior to himself.” [21]

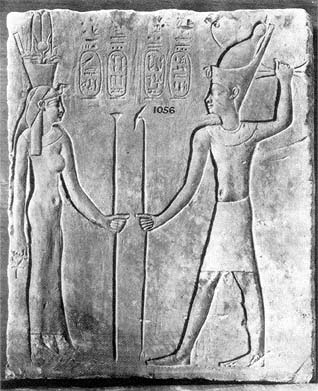

Nevertheless, in 279/8 B.C., the first Ptolemaiea was celebrated at Alexandria to honor Ptolemy II Philadelphus' deified parents, the “Savior Gods,” Θεοὶ Σωτῆρες, Ptolemy I Soter and Berenike I.[22] The seventeenth idyll of Theocritus similarly alludes to the institution of the cult of the defunct Soter at Alexandria by 270 B.C.[23] Claire Préaux's suggestion that the dynastic cult of the Ptolemies at Alexandria developed out of an original hero cult in honor of Alexander as founder of the city appears to be sound, and it implies that subsequent Ptolemies were incorporated therein by virtue of royal succession.[24] Nevertheless, as early as 272/1 B.C., Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Arsinoë II (figure 34) assumed the appellation Θεοὶ Ἀδελφοί (“Brother and Sister Gods”) and received a cult that was associated with the cult of Alexander.[25]

Fig. 34.Arsinoë II and Ptolemy Philadelphus as Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt. Tanis, 270–246 B.C. British Museum, London. From The Cambridge Ancient History, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), vol. 7, pt. 1, pp. 13–15, pl. 13.

How then can we explain the “great leap,” as Turner dubs it, from the cult of deceased ancestors to the veneration of living men? I would suggest that the two may be reconciled as distinct manifestations of divinity. The former was an extension of the hero cult instituted on behalf of Alexander; the latter was reverence generated by the manifestation of royal power.

In contrast with the Judaeo-Christian perspective of omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent divinity, the term theos possessed an extended range of meanings for an ancient Greek. It might denote an Olympian deity, a demigod, a hero, or a Hellenistic sovereign; it also was associated with miracle workers, the so-called divine men. Divinity was not construed as an absolute, but instead was an unstructured abstract signifying varying levels and nuances of power.[26] Hence it was in recognition of power, of achievements capable of exciting the popular imagination (to paraphrase Arthur Darby Nock),[27] that the earliest Greek ruler cult was established in 404 B.C. Even if the Ptolemaic dynastic cult originated as a form of royal propaganda, its continued success attests to popular belief.[28] As Simon Price, and now Professor Long, have both observed, it is futile to ask whether Greeks actually believed in the divinity of rulers; the only palpable evidence of their mental state is participation in cult or ritual.[29]

Although one might well be tempted to interpret the metaphorical description of Ptolemy II Philadelphus as θεὸς ἄλλος “another god,” by Callimachus in his Delian Hymn,[30] as hyperbole (representing either an expression of official propaganda or else a public manifestation of sycophancy, to both of which politically sensitive Greek administrators and beneficiaries of royal patronage would be wise to pay lip service), to dismiss it as such would probably be unsound. To call Philadelphus a god, given the broad range of nuances which characterized the significance of this term, was totally acceptable; theos merely implied recognition of a degree of authority in response to a ruler's mighty display of power.

What was the source of royal potency? Recently the traditional view that the ancient Egyptians considered their reigning pharaoh to be a deity in his own right has been challenged. Hans Goedicke maintains that it was not the king himself but rather the office of kingship that was divine.[31] Pursuant to numerous passages in Egyptian literature which emphasize the human nature of the Egyptian king, Georges Posener has argued that although the king was identified with certain deities—by means of representation in the form of a god or by exhibiting a feature or features unique to a specific divinity—the king himself was not divine.[32] It stands to reason, then, that the living Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt may have been similarly viewed: Ptolemy sat on the throne of Horus but it was the throne, not Ptolemy, that actually was divine.[33]

In his hymn to Zeus, Callimachus writes: “From Zeus come kings, for nothing is more divine than what issues from Zeus.” [34] Similarly, at Edfu, Kom Ombo, and Philae, Ptolemaic kings were depicted crowned by the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Buto; here, too, officially generated media portrayed the Ptolemies as divinely sanctioned, although in their own right they were not divine.[35] Kings were conceived as the representatives of traditional deities, especially Horus and Zeus, but not as their equals. This was the cutting edge of Demosthenes' and Diogenes' remarks.

The Socratic (Xenophon's Cyropaedia, Plato's Republic and Laws) and Aristotelian endorsements of the Good King's natural right to rule were no doubt well known to Greek intellectuals; but it was the Hellenistic philosophical schools that would elevate kingship from the natural to the divine plane—that is, kingship as a reflection of the divine—and catalog the Good King's many virtues.[36] Whether the position, voiced in the Letter of Aristeas, that the Ptolemaic monarch was human, ruling by the grace of God, owes more to the Jewish identity of the author or to his Greek education is, perhaps, a jejune question.[37] Various treatises of kingship were in general circulation, as confirmed by an anecdote preserved by Stobaeus: Demetrius of Phaleron is reported to have advised Ptolemy Soter to take an interest in books περὶ βασιλείας καί ἡγεμονίας on the grounds that “what friends do not dare to say to kings they write in books.” [38]

No doubt the portrayals of Ptolemaic kings and queens in the attitude of traditional Egyptian deities represent an attempt to conciliate old pharaonic traditions with the new regime. At Karnak, Edfu, and Philae, for example, the Ptolemies parade the same iconography as, are assimilated and identified with, and even receive life from, the traditional gods of Egypt.[39] The identification of the Ptolemies with Greek divinities and proclamations of their divine ancestry ought to be similarly understood.[40] These were advertisements of the divine origins of royal power.

The second aspect of the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship addressed by Professor Samuel is military leadership, especially the defense of Egypt from foreign enemies. These military exploits, recounted in the historical accounts of Polybius and Diodorus Siculus, were also celebrated by Theocritus in his seventeenth idyll.[41] On monumental architecture throughout Egypt, Ptolemaic kings may be observed grasping captured enemies by their hair with one hand, while the other is raised in a smiting position.[42] This scene is virtually identical to the numerous pharaonic ones.[43]

Another aspect of the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship addressed by Professor Samuel was philanthropia. Philanthropia might be exhibited in such diverse ways as the promotion of peace, the bestowal of liberal benefits on priests and temples,[44] grants of asylum or amnesty,[45] relief from famine,[46] tax exemption,[47] and protection against abuses[48]—the last of which neatly ties in with his thesis. Numerous royal prostagmata (ordinances) issued in response to petitions requesting favors or the correction of abuses attest to the concern of the Ptolemies for philanthropia.[49]

F. E. Adcock cynically claimed that Hellenistic kings traditionally represented themselves as benevolent toward their subjects because this was part and parcel of playing the game of proper royal etiquette,[50] while William Linn Westermann questioned whether Ptolemaic legislation, insofar as it is known to us, demonstrated any real concern for the welfare of Egyptian subjects.[51] Claire Préaux noted that philanthropia ordinarily occurs in societies in which there is an immense disproportion between the wealth and power of the few and the poverty of the masses.[52] More to the point, however, is Marie-Thérèse Lenger's observation that the basis of Ptolemaic philanthropia rested primarily on the concept of the king.[53] For Egyptians no less than for Greeks, Ptolemy was the protector of oppressed subjects; there is considerable evidence of Pharaonic precedent for this as well, most notably the Egyptian pharaoh's duty to ensure ma'at.[54] Consider the instructions of a Ninth or Tenth Dynasty pharaoh to his son, Merikare: “Do justice, then you endure on earth; calm the weeper, do not oppress the widow, do not expel a man from his father's property, do not reduce the nobles in their possessions. Beware of punishing wrongfully; do not kill, it does not serve you.” [55] I am not so rash as to suggest that philanthropia was a distinctly Egyptian as opposed to a Hellenistic concept, but rather that, at least insofar as the Ptolemies may have been concerned, there was already an established tradition for the pursuit of this ideal by the Egyptian king. Once established in Egypt, the Ptolemies appear to have dipped liberally into the springs of Greek philosophy—especially as supplied by the fourth-century Socratics, by Aristotle, and by Pythagoreans and Stoics—for rationalizations of their position as kings and of their philanthropia. Identical themes are echoed in Idyll 17, Theocritus' praising of his royal patron, Ptolemy II Philadelphus,[56] and in numerous papyri and inscriptions. Of course, the significant question (one that considerations of time prevent my addressing here) is the extent to which the Ptolemies actually lived up to the ideology of kingship they promoted—the fundamental distinction between Idealbild and Realbild.

As a social historian, I confess that I cannot imagine cultural exchange between the Greek and Egyptian inhabitants of Ptolemaic Egypt as having been one-sided. Nevertheless, the communis opinio among historians of Greek and Roman Egypt has traditionally been that Hellenic culture flourished in so alien an environment as Egypt as the result of a deliberate policy aimed at promoting Hellenization. As examples, I need only point to the Alexandrian libraries and Museum. It is, moreover, argued that since the Ptolemies regularly appointed and promoted Greeks to senior administrative positions, ambitious Egyptians would assimilate themselves with all possible speed to Hellenic culture if they hoped to advance their careers. Nevertheless, in a land such as Egypt, where terra sacra enjoyed such venerable antiquity, and where Hellenistic Greeks, no less than Egyptians, subscribed to the efficacy of the old Egyptian cults, it is, I would argue, hard to sustain the conclusion that Egyptian religion did not exert an influence on the Greek colonists.[57]

Throughout the pharaonic period, Egyptian religion and administrative tradition concerned themselves intimately with the ideology of Egyptian rulers. They appear to have contributed no less significantly to the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship. The Ptolemaic monuments at Karnak, Edfu, Kom Ombo, and Philae, situated in plain view of all subjects, Egyptians and Greeks alike, celebrated an ideology of kingship that deliberately emulated pharaonic prototypes. These monuments do not advertise an Egyptian ideology of kingship as distinct from a Greek one, but rather demonstrate a coalescence of the two.[58] To balance Professor Samuel's emphasis on the Hellenic component, I have stressed the Egyptian.

It would be unreasonable to assume that the Ptolemies were uninterested in Aegyptiaca. Consider the traditions that imply Ptolemaic patronage of the Egyptian priest, Manetho, whose treatises on Egyptian history and religion were frequently cited by subsequent classical authors.[59] Whose benefit, if not that of the Ptolemies, did Hecataeus of Abdera's reconciliation of Egyptian antiquities with Greek political philosophy serve?[60] Indeed, as early as the sixth century B.C., Athenians and Ionian Greeks had been exposed to Egyptian traditions by virtue of their commercial activities at Naukratis and further inland, while fully a century before Alexander cast his spear into Asia or the Macedonians set foot on Egyptian soil, Herodotus so marveled at Egyptian traditions that the entire second book of his Histories was devoted to a discussion of them. The accounts of Diodorus Siculus and Strabo demonstrate that Aegyptiaca continued to fascinate Greek intellectuals into the Roman period. And is it not the remarkable intellectual curiosity of the ancient Greeks that posterity has lauded as the essence of Hellenism?