| • | • | • |

§ 2. The Mechanician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805–1871)

The automaton-builders who made imitations of skilled human beings had a variety of purposes. Vaucanson probably conceived his automata, at least originally, as scientific projects. The Jaquet-Drozes conceived theirs as lux-ury products. Kempelen conceived his to impress his sovereign. But gradually the conception of automata as exhibition pieces, Maelzel’s conception, prevailed over all others. And gradually the show prevailed over the machinery, so that many builders exhibited quasi-automata and pseudoautomata in place of true automata. Although the pseudo-automaton seems degenerate, a soulless copy of the true automaton, it retained two of the most attractive charms of the true automaton: imitation and deception. The pseudo-automaton, just like the true automaton, imitated something else and in doing so deceived people into believing it could do what that something else did. Automata were a kind of magic trick, and they and magic shows had their vogue together.

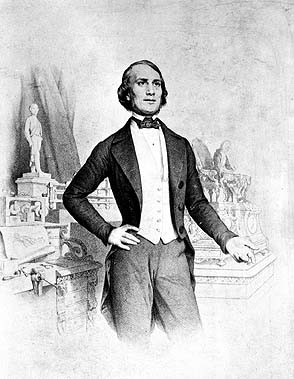

Portrait of Robert-Houdin. Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Photograph by the Library of Congress Photoduplication Service.

If the name Robert-Houdin is familiar at all to Americans, it is because America’s most famous magician, Harry Houdini, born Ehrich Weiss, renamed himself after this most famous magician of France, born Jean-Eugène Robert. “When it became necessary for me to take a stage-name, and a fellow-player, possessing a veneer of culture, told me that if I would add the letter ‘i’ to Houdin’s name, it would mean, in the French language, ‘like Houdin,’ I adopted the suggestion with enthusiasm.” From the very beginning of his career Houdini strove to imitate Robert-Houdin: “My interest in conjuring and magic and my enthusiasm for Robert-Houdin came into existence simultaneously. From the moment that I began to study the art, he became my text-book and my gospel.” As of the late nineteenth century, when Houdini was growing up, not many first-class magicians had written books about conjuring techniques, as Robert-Houdin had; fewer still had written an autobiography describing their experiences, as Robert-Houdin had; and none of their lives had been as fascinating as Robert-Houdin’s had been. Houdini in turn wrote books about conjuring techniques, one of which he called The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin: “In the course of his ‘Memoirs,’ Robert-Houdin, over his own signature, claimed credit for the invention of many tricks and automata which may be said to have marked the golden age in magic. My investigations disproved each claim in order.” [53] But Robert-Houdin’s claims were no more exaggerated than those of the other stage magicians discussed by Houdini, whose inventiveness generally consisted of reworking or reclothing old tricks. Houdini eventually came to realize that the real deceptions in his book were his, not his model’s, although he could only bring himself to acknowledge one: “The only mistake I did make was to call it the name I did when it ought to have been ‘The History of Magic.’” [54] Everything having to do with stage magic, even writing about it, comes down to imitation and deception.

Robert-Houdin remains today one of the revered masters of the “tricks and automata which may be said to have marked the golden age in magic,” to use Houdini’s phrase, which reflects the consensus of historians of magic on the advanced state of that art in the early and mid-nineteenth century.[55] So was the Frenchman essentially a magician and only incidentally a mechanician? Houdini’s phrase implies the answer: Legerdemain and automaton-building were considered two branches of the same tree of magical knowledge. From the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, most conjurers worth their saltpeter presented mechanical humans or animals in their shows. After all, both sleight-of-hand tricks and mechanical marvels demonstrated manual dexterity. And both legerdemain and automata featured deception: The power of the former depended on the implication that something supernatural was happening; the power of the latter on the implication that a machine could do what a human being or an animal can do. Watching a feat of legerdemain, the spectator’s mind was not persuaded of the presence of something supernatural, but the spectator’s senses were baffled. Watching an automaton, the spectator’s senses were not persuaded of the presence of a living being, but the spectator’s mind was perplexed by the thought that a living being might be no more than a very complicated machine. In neither case was the implication demonstrated, but in both cases it seemed to have been. As for Robert-Houdin, he built machines of one sort or another throughout his life and gave magic shows for only around a decade.

Jean-Eugène Robert was born in 1805 in the small town of Blois, which lies on the Loire River about a hundred miles south-southwest of Paris. His father, Prosper Robert, who had his own business, practiced clockmaking and related arts: “an excellent engraver, a jeweler of taste, he could even if need be sculpt an arm or a leg for a mutilated statue.” So boasted the son, anyway, who as a child wanted nothing more than to imitate his father. “I am tempted to believe that I came into the world with a file, a compass, or a hammer in my hand, because from my earliest childhood, these instruments were my toys, my playthings.” His early inclinations notwithstanding, his father sent him to Orléans, a large town nearby, to attend its collège, a secondary school designed to prepare its students for either higher education or direct entry into a professional career. Prosper Robert had the normal ambition to push his child at least one rung further up the social ladder from his own position. Jean-Eugène studied diligently if unenthusiastically and returned to Blois a graduate at the age of eighteen. His father, pleased by this success, allowed him to idle away a few months doing whatever he wanted, during which time he saw a sleight-of-hand artist perform on the street. “It was the first time I ever attended such a spectacle: I was amazed, stupefied, dumbfounded.” Finally Prosper asked his son to choose a profession and found that Jean-Eugène stubbornly clung to his desire to become a clockmaker.[56]

The equally stubborn father placed his son in a notary’s office. A notary in nineteenth-century France was a kind of second-class attorney, handling a lot of routine legal documents; the occupation was low in the ranks of the professions, but it was a profession. “I leave the reader to imagine how this automaton’s labor suited my nature and my mind: pens, ink, nothing was less appropriate to the execution of the inventions for which I ceaselessly generated ideas.” Jean-Eugène suffered a notary copyist’s boredom for three years, spending much of his free time and some of his work time building mechanical gadgets. Finally, whether because his son had bowed to his wishes for so long, because his son’s stubbornness had proven superior to his own, or because he had ceded all further resistance in ceding his business to his nephew—Jean-Eugène’s cousin—the retired clockmaker agreed to allow his son to apprentice in his old shop under the supervision of its new owner.[57]

Jean-Eugène Robert had found his way to half of his vocation. The other half, at least according to his autobiography, Confidences et révélations, found its way to him. Going out to a bookstore one day to buy a book on clockmaking, he returned with a book on conjuring that the bookseller had wrapped up for him by mistake. This “wrong book” enchanted him, so he set out to learn legerdemain.

After completing his apprenticeship under his cousin, Jean-Eugène went to work for a clockmaker in nearby Tours. Whenever he had a free hand, sitting at his workbench, he continued to practice card and coin manipulation.[58]I had often been struck by the facility with which pianists were able to read and execute, even at first sight, a melody and its accompaniment. It was clear to me that through practice one could create both an ability to see at a glance and a skill at the keyboard that allowed an artist to read several different things simultaneously while at the same time his hands were doing something very complicated. Now it was a similar ability that I wanted to acquire in order to apply it to prestidigitation; however, as music could not provide me with what I needed, I had recourse to the art of juggling.

I placed a book in front of me, and while my four balls flew in the air, I accustomed myself to reading without hesitation.

In conformity with the style of the period, I had on each side of my frock coat, called a frock coat à la propriétaire, pockets large enough so that I could easily move my hands around inside them. This was advantageous to me in that whenever one of my hands was not occupied with something outside, I could slide it into one of my pockets and begin to work with cards, coins, or one of the other objects that I have mentioned.

The wrong-book episode in Robert-Houdin’s autobiography is followed by the still less believable Torrini episode, which takes up almost a quarter of his book but not even a year of his life. Once, he writes, he fell sick from food poisoning. He became feverish, delirious, possessed by the idea that he was going to die and then by the desire to die at home in Blois. He managed to get into a public coach, fortunately empty, but the jolting of the vehicle gradually made the ride more and more unbearable to his rebellious intestines, and he finally jumped out, rolling unconscious to the side of the road. He came to himself after an unknown period of time in an unknown moving vehicle. It turned out to be a large wagon that when closed up served as living quarters and when opened out served as a small stage for an itinerant magician who gave performances in provincial towns and villages. The magician, named Torrini, and his assistant, Antonio, had picked him up out of the road and were now nursing him back to health. He repaired an automaton for Torrini, proved himself generally useful with his mechanical skills, toured with the pair for an unspecified number of months, and was gradually initiated into the secrets of professional conjuring. Torrini told him many stories of his travels and of other magicians, including an absurd tale involving Giuseppe Pinetti, whom he claimed to have driven out of business with his superior magic. Pinetti had been the most famous magician in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century, surpassing even “Comus,” Vidocq’s childhood employer. Eventually Torrini confided that his real name was Edmond de Grisy; that his father had been a count; that he himself was a doctor turned magician; that the young clockmaker he had found half-dead in the road reminded him of his dead child; that he had accidentally killed the latter on stage doing a William Tell trick; that his wife—Antonio’s twin sister—had died of grief soon thereafter; and that Torrini was really Antonio’s surname, the whole implying that he, Grisy, was doomed to wander aimlessly for the rest of his life in a state of self-alienation. Finally returning to his own story, Robert-Houdin tells us that he substituted for Torrini/Grisy on stage after the latter was hurt in a crash of his wonderful all-purpose vehicle. The young clockmaker quickly earned enough to pay for the restoration of both the magician and his wagon. Bodies and souls healed all around, Torrini/Grisy drove off into the sunset and Robert-Houdin returned to Blois. “I found my father quite calm with respect to me. The reason was that, in order not to arouse his anxiety, I had used a ruse: A clockmaker of my acquaintance had forwarded my letters to him as though they came from Angers, and this friend likewise took the responsibility of sending me his responses.” [59]

The many improbabilities in the Torrini episode tell the reader that it is a deception. The episode’s final story of how Robert-Houdin deceives his father, both by its extreme improbability and by the fact that it says outright that Robert-Houdin is a deceiver, drives the point home. There are undoubtedly elements of truth in the episode, but no one has yet succeeded in finding a historical trace of Torrini/Grisy. The Torrini episode is the wrong-book episode writ large. In both episodes, destiny, or at least events outside the young clockmaker’s control, lead him to the study of magic. That is, he cannot be blamed for any inconstancy toward the career he had insisted to his father so stubbornly on pursuing. Besides, magic is something he practices under the table or inside his pocket, in the wrong-book episode, or while recovering from an illness or on leave from his job, in the Torrini episode; in short, it is not to be counted as part of his real life. It is only a dream: a secret life, an imaginary life, an ideal life. He will continue to satisfy his duty toward his father, represented by his father’s nephew, under whom he serves his apprenticeship in the wrong-book episode, and by Torrini/Grisy, in the Torrini episode. But he will also satisfy his own desire to have a successful career as a magician. Both episodes are deceptions, but like those of a stage magician they are harmless, entertaining deceptions: The audience experiences the comfort both of seeing the conventions of society observed and of being informed that a deception is taking place, while at the same time it experiences the excitement of knowing it is being deceived without being able to figure out exactly how. For Robert-Houdin, the entertainer’s goal is to arouse wonder in his audience, or, put negatively, to avoid boring it with humdrum reality on the one hand or shocking its sensibilities on the other. An autobiography, like an automaton, should be a transparently deceptive, but still deceptive, copy of life.[60]

His adventure having arrived at its happy conclusion, the young mechanician is placed by his older self back into his former position as a cog in a clockmaker’s workshop. Back to the boredom of the daily round of cleaning and repairing clocks. Back to familial Blois. But soon he was to meet a local clockmaker who had moved to Paris and built up a thriving business there, and who had a daughter. In 1830, the year of the July Revolution, of which there is no mention in his autobiography, Jean-Eugène Robert married Mademoiselle Houdin and went to work for Monsieur Houdin. In order to distinguish himself from the many other people in Paris named Robert—some of them also clockmakers—he appended his bride’s name to his own, an addition he later legalized, becoming Robert-Houdin.[61]