| • | • | • |

Response: J. J. Pollitt

It would be appropriate to the taste and style of the Hellenistic Age if Martin Robertson and I were to confront and challenge one another with radically different views of Hellenistic art. Unfortunately, I find myself in substantial agreement with almost everything he has said, and even our minor differences of opinion—such as our differing view of the role of oriental art in the development of naturalistic portraiture—are really only matters of emphasis.

I think, however, that I can stage a confrontation of another sort that may turn out to be equally interesting. In correspondence and conversation with Professor Robertson it has become clear that this symposium has provoked both of us to take a fresh look at Hellenistic art and to reassess our earlier evaluations of its basic character. In a sense, this meeting seems to have forced us to have a confrontation not with one another but with ourselves. In his great history of the whole of Greek art[1] and in my recent book on Hellenistic art[2] both of us tended to dwell on how the innovative features of Hellenistic art could be explained as responses to new social and political conditions of the period—the wider geographical horizon in which Greek art flourished, the advent of Hellenistic kingship, the growth of large urban centers with mixed populations, and so on. It is quite natural, when you are writing books of that sort, to look for what seems new and distinctive in the period with which you are dealing. Now that we have stepped back from that task, however, both of us seem to have found that in trying to define what was new we tended to deemphasize the continuity between Hellenistic art and earlier Greek art, a continuity that we would now agree was, in fact, very strong.

In my own book on Hellenistic art I emphasize five new attitudes in the Hellenistic Age that played a role in shaping its art. A new instability in systems of government, in the settlement of populations, and in the expectations of individuals for a settled life, led, I argue, to an obsession with fortune that is reflected in such things as the popularity of images of Tyche, in the appeal of images of Alexander for their seemingly talismanic power, and in the fascination with dramatic reversals of fortune (as, for example, in the painting that was the source of the Alexander mosaic). I also point to a theatrical mentality that grew out of the conviction that life in the Hellenistic period had somehow become a play written by fortune in which one must play one's part. The popularity of images from the theater in the decorative arts; the fondness for dramatic portraits that conveyed trials of the spirit (e.g., the Lysippan portraits of Alexander); the love of dramatic narrative crises (the Granikos monument, the Alexander sarcophagus); dramatic settings both for buildings (the Pergamene acropolis, the temple of Athena at Lindos) and for sculptural groups (the “lesser Attalid group” in Athens, the Nike of Samothrace); and, on a purely stylistic level, the prevalence of the “Hellenistic baroque” style, can all be seen as emanations of this new mentality.

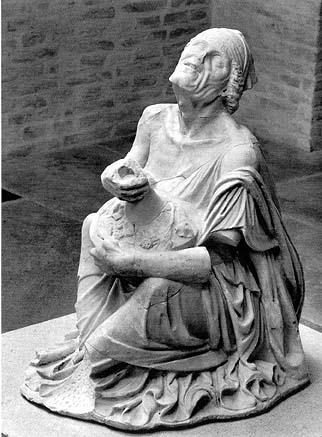

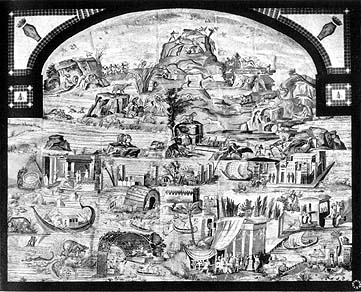

As others have long argued, the social instability of the Hellenistic Age and the decline of small, tightly knit communities contributed to the development of still another distinctive mind-set of the Hellenistic period, individualism. The interest in distinct personalities in portraiture; the concern for individual states of consciousness such as fear, pain, drunkenness (see figure 18), or erotic excitement; and the exploration of personal religious emotion in the images of Sarapis and in mysterious architectural spaces like the Arsinoeion and Hieron at Samothrace, all reflect this new concern for personal, rather than communal, experiences and values. The corollary, as Tarn put it,[3] of individualism was a cosmopolitan outlook, a sympathetic curiosity about the entire inhabited world that lay beyond one's own social and ethnic traditions. Thus foreigners, derelicts, and exotic fauna and flora are all treated with interest, and usually with sympathy, in Hellenistic art (see figure 19).

Fig. 18.Drunken old woman. Roman marble copy of third- or second-century-B.C. original. Glyptothek, Munich. Photo Chr. Koppermann.

Fig. 19.Nilotic mosaic from Palestrina, circa 80 B.C. Museo Prenestino-Barberiniano, Palestrina.

Finally, there was the scholarly mentality that grew out of royally subsidized intellectual centers like the Library and Museum of Alexandria, which brought a didactic, learned quality to Hellenistic art that is expressed in such things as complicated allegories—for example, the stele of Archelaos (figure 20)—and in the learned, evocative pleasure that was derived from reviving and playing with earlier artistic styles, archaism and neoclassicism (see figures 21 and 22).

Fig. 20.Marble votic relief by Archelaos of Priene, circa 150 B.C. British Museum, London. Photo British Museum, courtesy of Trustees.

Fig. 21.Neo-Attic Maenad relief. Marble, circa 100 B.C. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Photo Alinari.

Fig. 22. Terme Boxer. Bronze, second or early first century B.C. National Museum of the Terme, Rome. Photo Alinari.

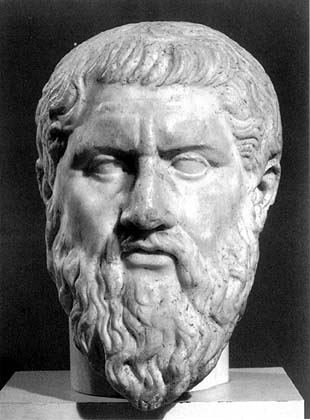

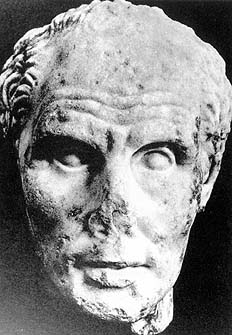

It is not my intention, like some beleaguered bureaucrat in a Marxist state whose policies have failed, to recant the line of thought that I have just sketched—I still think that it has basic validity—but I would like for a moment to look at Hellenistic art from another point of view. As Martin Robertson has emphasized in his paper, after one does one's best to identify what is really original about Hellenistic art, one keeps coming back to the unavoidable observation that most of the major developments of Hellenistic art grew quite explicably, if not entirely predictably, out of earlier Greek art. Until quite late in the period, when Hellenistic artists faced the challenge of satisfying the needs and taste of Roman patrons, there are no changes that one would be inclined to call revolutionary. Precedents for most of the major developments of Hellenistic art can be found in the art of the fourth century B.C. or even earlier. For example, a realistic trend in portraiture is anticipated in a number of portraits that belong to the fourth century. I would cite, in particular, those of Xenophon and Plato (figure 23)—although on the latter, let it be noted, Martin Robertson disagrees.

Fig. 23.Portrait of Plato. Roman marble copy of fourth-century-B.C. original. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. By permission.

Dramatic confrontations, and their accompanying pathos, can be found in the pedimental sculptures from Epidauros and Tegea, as well as in other sculptures, and literary sources suggest that they were explored in the paintings of Euphranor, Nikias, and Aristeides. The increasingly widespread use of personifications, including related groupings of personifications (e.g., Demokratia and Demos in the presence of Theseus in Euphranor's paintings in the Stoa Basileios in Athens) anticipate the didactic allegories of Hellenistic art. Personal religious emotions are anticipated in fourth-century images of Asklepios and perhaps in the unorthodox, mysterious interior of the temple of Apollo at Bassae. A retrospective view of style seems already to be present, on a limited scale, in the fifth century B.C. in the mannerism of the Pan Painter and the archaism of the sculptor Alkamenes. The “boy strangling a goose” type and other well-known Hellenistic images of children, while admittedly treated more playfully and lovingly than images of children had been in the classical period, represent the continuation of an earlier tradition of votive images of children. Even those images that are often thought to constitute social realism in Hellenistic art—old fishermen (figure 24), peasant women (figure 25), dwarfs, and the like—were anticipated in brief flashes in Greek vase painting (I think of the foreign-looking gentleman and his dog on the cup that is the name-vase of the Hegesiboulos Painter in New York [figure 26]) and apparently, judging by the literary evidence, in the art of the sculptor Demetrios of Alopeke.

Fig. 24.Old fisherman. Roman marble and alabaster copy of original of ? 200–150 B.C. Louvre, Paris. Photographie Giraudon.

Fig. 25.Old market woman. Marble, late second or early first century B.C. Metropolitan Museum, New York. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1909.

Fig. 26.Red-figured kylix attributed to the Hegesiboulos Painter. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1907.

In short, there are good reasons for concluding that what is “Hellenistic” about Hellenistic art is a matter of new emphasis rather than radical departure. There is a new look to many things, but continuity with the past is equally striking.

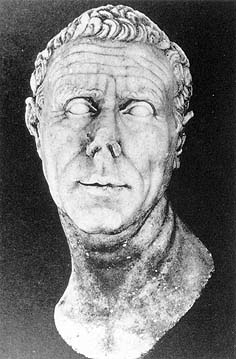

The one period in which this general observation seems not to be entirely true occurred, as I said earlier, in the late Hellenistic period when the resources of Hellenistic art were being put at the disposal of Roman patrons. In the Greco-Roman phase of Hellenistic art there were a few developments that seem to have had no clear Greek precedent and must be viewed as altogether new. A change that was clearly unprecedented, as Martin Robertson has observed, was the extension of the portrait sculptor's art to represent ordinary people who could claim no public distinction. We are, of course, familiar with such portraits in Roman art, where not only prominent public officials but also people of relatively low status—freedmen, for example—commissioned portraits. In the Greek world, on the other hand, portraits had always been reserved for people who were credited with some great achievement, such as military heroes, leaders in government, victorious athletes, or renowned philosophers, poets, and orators. In Greek portraiture, the “average person” was simply not of much interest. When viewed against this background, that remarkable series of realistic portraits found on Delos, dating from the late second and early first centuries B.C. and representing what seem to be Italian, Greek, and eastern Mediterranean businessmen (see figure 27a, figure 27b, appears quite remarkable and clearly constitutes something new. Such evidence as there is indicates that the artists who made them were Hellenistic Greeks; but they flourished in an international culture which was something other than traditionally Greek, and this culture challenged them to create an unprecedented genre.

Portrait from Delos, second or early first century B.C. Delos Museum. Exploration Archéologie de Délos, vol. xiii, pls. xxi, xxiii.

Portrait from Delos, second or early first century B.C. Delos Museum.

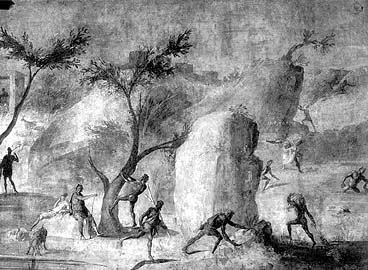

The atmospheric style of landscape painting that we find in the Odyssey landscapes (see figure 28) may be another example of an unprecedented development in Hellenistic art, although in this case, given the paucity of surviving Greek paintings, it could be argued that the Greek antecedents simply have not survived.

Fig. 28.Odyssey landscape: attack of the Laestrygonians. Vatican Museum, Rome. Photo Alinari.

A final thought. This symposium has provoked a number of interesting reflections on the role of frontiers in the Hellenistic world. The chief fountain of inspiration for the artists of the Hellenistic period was undeniably old Greece, but to the extent that they were affected by frontiers, I think it can be asserted that the most influential one was not the Sudan or the Hindu Kush; it was the Tiber.