| • | • | • |

The Character and Fate of Popular Protestantism

As popular protest gave way to civil war, the character and fate of popular political action varied considerably, and it is this pattern of variation that is our chief concern here. In retrospect, it is perhaps tempting to conclude, as Henry Heller (1991) does with regard to the French Huguenots, that the heavy hand of elite leadership in the context of open warfare sidetracked or even stifled the growth of an otherwise promising popular evangelical movement. At the local level and in the short term, however, it often seemed as if the popular movement was in the driver’s seat, forcing otherwise tentative or cautious elites to make choices or take risks that they would much rather have avoided (Benedict 1981:chap. 10). But rather than generalize in this strictly dichotomous fashion, let us look briefly at a series of examples that illustrate the range of variation and highlight the complex relationship between religious dissent and political revolt.

To the extent that religious conflicts in France and the Low Countries grew out of the political pressure of local reformation coalitions on variably receptive municipal authorities, they may be said to reflect the same political dynamics as were evident in the urban reformations in Germany (see fig. 4 above). As we shall see, however, the politicization and nationalization of the complex problems of religion and regime in France and the Low Countries produced a distinctive pattern of direct political and military contestation between two “religious” parties—Reformation and Counter-Reformation coalitions. Indeed, the long years of often violent struggle require us to imagine a rather different set of political interactions that tended toward rather different (though, in many cases, equally transient) outcomes, including both civil war and the formal accommodation of religious difference, which was conspicuously absent in the First Reformation.

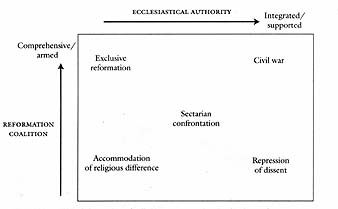

Thus, Figure 6 describes and accounts for the distinctive features of this second round of reformation conflict in terms not only of variations in the character and capacity of the Reformation coalitions—highlighting its social comprehensiveness as well as its military capacity—but also of variations in the character and capacity of established religious authority—highlighting especially the extent to which the Church was integrated with political elites and enjoyed the support of popular political actors within a larger Counter-Reformation coalition. We shall return to these broader comparisons later, but first we must disaggregate the larger historical constructs—the French Wars of Religion and the Dutch Revolt—and locate the variety of conflicts within concrete political spaces. Let us begin with the example of Toulouse.

Fig. 6. Political dynamics of political contestation in the Second Reformation

In the southern French city of Toulouse the leaders of the newly organized Reformed church—the consistory as well as some of the city’s notables—met urgently on the evening of May 11, 1562, and decided, in light of the rapidly accumulating evidence of civil war more generally between Catholics and Protestants in France, to take immediate action.[29] Armed Protestants were surreptitiously let into the city, occupied the Hôtel de Ville, and took several capitouls, the city’s chief magistrates, prisoner. They subsequently moved quickly to occupy several colleges of the university and to erect barricades across key streets so as to fortify those sections of the city in which they were able to establish themselves before dawn. Though this well-planned coup was initially successful, rumors of an armed Protestant uprising had compromised the element of surprise, and the Catholics were prepared to meet the Protestant challenge; indeed, the Catholics enjoyed a clear advantage in the numbers of armed men immediately available in the city, although the Protestants benefited from the armaments, including cannons, they captured in the arsenal of the Hôtel de Ville. Four days of very destructive urban warfare, beginning on May 13, finally yielded to a truce on May 16, which amounted to a capitulation by the Protestant forces.[30] A guarantee of limited safe passage afforded the Protestants only marginal protection from the vengeance of their Catholic enemies when their mass exodus from the city was completed by the evening of May 17. By the time the dust had settled, as many as four thousand people may have died.

These dramatic, albeit exceptionally fast-moving and destructive, events in Toulouse encapsulate clearly some of the most important general characteristics of political and religious conflict in the second phase of the European Reformation: the integral involvement of ordinary people at the community level; the deep religious/sectarian divisions within communities; and the final arbitration of armed might, more often than not in alliance with actors outside the community. But the conflagration at Toulouse also announced the more specific theme of short-term success followed by ultimate failure for the Reformed Protestants, a theme that was replayed with often devastating variations in many communities not only in France but in the Low Countries as well. In the Walloon town of Tournai, for example, we can see in rather slower motion and more vivid detail the political dynamics of what was essentially a revolutionary process that exploited the complex relationships among a popular religious movement, locally vulnerable magistrates, and an implacable but distant sovereign (see esp. Steen 1985; Le Barre 1989).

As early as 1563 a crowd of perhaps two thousand evangelicals openly chanted psalms and listened to sermons in the streets of Tournai after authorities had broken up clandestine meetings in the countryside; some in the crowd even boasted, “They [the authorities] do not wish us to sing in the woods where we bother no one, so we will sing in the city; and if they put in a garrison of one thousand, we will raise two thousand” (quoted in Steen 1985: 49–50). Such bravado notwithstanding, the local Reformed Protestant movement remained generally invisible until the surprising summer of 1566. Then, in Tournai as elsewhere in the Low Countries, the popular dimensions of the evangelical movement became fully visible in the massive crowds that thronged to worship services just beyond the immediate jurisdiction of the urban magistrates who were continually pressured to enforce the central government’s uncompromising placards against heresy. On one such occasion, Pasquier de Le Barre, a local notable who chronicled these events, reports, “In open defiance of the magistrates, the flower of Tournai was in attendance, leaving so few people of quality behind in the city that no one could remember the like, even during times of war and adversity that the place has suffered” (1989: 102).

Indeed, the steady growth of popular support for the evangelical movement produced a locally formidable coalition, led by the Reformed consistory and supported by the guilds, that local authorities were unable to resist.

And well they might be anxious, for after iconoclastic crowds “cleansed” the city’s churches in August, the Reformed Protestants not only moved their services inside the walls and indoors, but the preachers and members of the consistory who claimed to speak for the movement forced their way into the exclusive domain of the local town council’s deliberations, pressing a program of popular armament and religious reform. Still, a hastily assembled citizen’s militia of about four thousand appeared to be no match for the small royal garrison and the army that Margaret of Parma raised to support it. Thus, following the defeat of a rebel “army” near Lille on December 27, Tournai was quietly occupied by royal troops in January 1567. Though there was little bloodshed inside Tournai, the city paid a very high price for its brief Reformed Protestant rebellion: a period of harsh persecution (with more than 1,000 condemnations) was followed by the complete dissolution of Tournai (and the Tournésis) as a separate province.Recognizing their own inadequacy in the face of the problem, some magistrates began to worry about [the governor general’s] repeated warnings that the King would someday demand an account of their regime and find them wanting. However, the King who was far away inspired much less concern than did the people of Tournai itself, for the fervor of the masses of people who went to sermons began to make the magistrates anxious. (Steen 1985: 70–71)

A similar scenario was played out in nearby Valenciennes where, in the absence of a local garrison, it took a siege that lasted until March 24, 1567, to end the city’s defiance of Philip’s authority (Clark 1972; Parker 1985: 93–98). Likewise, at Rouen during the first French civil war, a royal siege forced the surrender of a rebel Huguenot regime (Benedict 1981). At Lyon, by contrast, the rebel Huguenot regime that seized power in the spring of 1562 lasted until 1567, but it, too, ultimately failed under pressure from a potent countermobilization in defense of the established Church (Davis 1975). What all of these cases have in common is that a locally formidable reformation coalition—which brought together notables, bourgeois, and artisans under the leadership of the local Reformed consistory—opted, in the heady atmosphere of escalating political crisis during the 1560s, for a course of action that amounted to local revolution;[31] yet lacking outside help in the face of a spirited defense of the established regime, these revolutionary regimes ultimately failed not only to bring on the Calvinist millennium but also to preserve even a limited space for public evangelical worship. In the terms suggested by figure 6, all of these cases moved quickly from a common starting point in the lower right—the repression of dissent—toward sectarian confrontation in the center; in addition, each was engulfed in the larger pattern of civil war that thrust them back toward the forceful repression of dissent.

In other cases, of course, the defeat of the Reformed Protestant movement was not predicated on a sudden coup or even the apparent pretense to found a revolutionary regime. In Amiens, for example, though Protestantism appealed to a broad spectrum of the local population, the Reformed community never joined the political alliances or took on the political aspirations of their coreligionists in Toulouse or Rouen—which had roughly similar levels of popular support in the total urban population—at the beginning of the French civil wars (Rosenberg 1978); having remained politically discreet at the height of Huguenot strength, then, the local reform movement quickly found itself on the defensive in Amiens as the conflict and warfare escalated elsewhere. Similarly, across the border in the Habsburg Netherlands, despite a sizable evangelical movement in the region, Reformed Protestantism was held in check in Lille (a close neighbor of Tournai and Valenciennes) as the local elite remained firmly united in its resistance to religious change; thus even in the summer of 1566 the Reformed Protestants of Lille were unable to exploit the fleeting opportunities for bold dissent that others seized where elite loyalties were more clearly divided or their policies uncertain (DuPlessis 1991). At the heart of the Valois domain, the city of Paris presents yet another variation on this theme. Home to a sizable Reformed community and torn by sectarian violence throughout the 1560s, Paris nevertheless remained the political and cultural capital of the “most Catholic” French kingdom; indeed, short of conversion of the monarchy to Protestantism and conquest by Huguenot armies, it is hard to imagine a scenario in which the people of Paris might have been free to establish an entirely new religious regime or even a publicly dissenting church.[32] In these cases, then, evangelical dissent did not in fact connect with political revolt in the experience of ordinary people for a variety of reasons, each of which reflects the locally specific structures of political opportunity as much as the absolute strength of the movement itself.

It would surely be mistaken, however, to dwell on examples of the failure of religious dissent during the Second Reformation, for eventually dissenting communities established themselves as public churches and drew on both elite alliances and popular support in large stretches of both France and the Low Countries. Here again, the character and the fate of local interaction were quite variable. La Rochelle, an important port on the west coast of France, is illustrative of a number of French cities, primarily in the south and southwest, where in the early 1560s Reformed Protestantism quickly attracted majority support among the urban population without serious resistance from the religious and political establishment.[33] Indeed, despite considerable division between the oligarchical corps de ville and the city’s bourgeois citizens over alleged abuses of power by municipal officials earlier in the century, the Reformed church, which claimed at least forty-two of the one hundred members of the corps de ville among its congregation, boldly but peaceably inserted itself into the public arena without an open break with the local political regime. What is more, during the first civil war in 1562–1563 and against the backdrop of very serious municipal conflicts with the Crown in the 1540s and 1550s, this openly Protestant city managed to resist considerable pressure to ally itself with the Huguenot rebellion more generally and even continued to proclaim its loyalty to the king. Thus it was that the successful establishment of Reformed Protestantism in La Rochelle invoked neither the “Great” nor the “Little” tradition of revolt, both of which had been prominent features of recent Rochellais history. The “moderates” who had managed to steer this remarkable course were, however, temporarily swept aside in the second war (1567–1568) by “zealots,” who insisted on alliance with the Huguenot party and the suppression of the Catholic church, and although the moderates quickly returned to power, they also formally negotiated an alliance with the Huguenot party when the city was threatened with a royal garrison in the third war (1568–1570). Henceforth, La Rochelle remained an important Huguenot stronghold until the Edict of Nantes guaranteed its position as a place of Reformed worship and surety in 1598.

Although the experience of La Rochelle was in some sense exceptional, it nevertheless illustrates the experience of those communities in which the popular evangelical movement enjoyed explosive growth, with or without the active support of local elites, and an increasingly Protestant community as a whole managed to avoid outside intervention to restore the Catholic church, with or without the support of the broader Huguenot alliance. Thus Reformed Protestantism quickly gained the upper hand and remained in a dominant cultural position in cities like Nîmes, Montpellier, and Montauban as well as a broad range of small towns in the south and west of France. In the course of the civil wars, and especially in the aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew’s massacres in 1572, the religious and political leaders of these places where Protestantism had gained the upper hand moved to establish not only a new national church but also a politically independent confederation—what Janine Garrisson (1980) has called les Provinces Unis du Midi—outside the immediate domain of a severely crippled monarchy. Although these self-governing communities would certainly be considered rebellious from the point of view of the monarchy, in the experience of ordinary people within these Huguenot strongholds, a fully institutionalized Reformed Protestantism, with its corporate discipline and generally austere morality, undoubtedly seemed the very opposite of rebellious (see, e.g., Segui 1933). In all these cases, then, amid the genuine uncertainty of the early 1560s, we can see an exit from the starting point of repressed dissent in the direction of initially local and informal accommodations of religious differences followed by locally variable movements in the direction of exclusive reformations.

Yet another scenario for Reformed Protestant success may be seen in the experience of the rebel cities of the northern Low Countries after 1572. Following the hedgepreaching and iconoclasm of 1566, the notoriously repressive regime of the duke of Alva had driven both religious dissenters and political opponents either underground or into exile. Yet the capture of the small town of Den Briel on April 1, 1572, set off what Geoffrey Parker (1985) calls the Second Revolt in which the Beggars established a more or less permanent territorial base within the Low Countries from which to challenge the Habsburg regime militarily. This outcome was far from certain as, at first, only widely scattered cities took the side of the Beggars (see Parker 1985: 139 map). By September, following a strategic retreat toward the south by the duke of Alva, the map of rebel-held territory had begun quite dramatically to fill in especially in the north, only to be pushed back by a Spanish counteroffensive almost exclusively into the provinces of Holland and Zeeland by the end of the year—with the notable exception of cities like Middelburg and Amsterdam that remained loyal to the king (see Parker 1985: 143 map). In this new cycle of revolt some cities like Valenciennes replicated the wonderyear experience of only short-lived success for religious and political revolt. In Holland and Zeeland, however, a number of cities established new political and religious regimes that survived the test of time and the depredations of intermittent civil war.[34]

In cities like Leiden and Delft, which had experienced both the iconoclasm of 1566 and the repression that followed, there was a residue of resistance to Spanish tyranny that quickly reemerged in the form of popular demonstrations in 1572 in response to the news of rebel success elsewhere, but an official shift to the rebel cause awaited the arrival of rebel troops and a change in the local magistracy (Boogman 1942; Kooi 1993). Then, of course, religious dissenters suddenly enjoyed opportunities for both demonstrative and organizational activity, the latter aided by both the return of exiled leaders and the organization of district-level classes and regional synods on the Calvinist model. Even in places like Gouda, Dordrecht, and Rotterdam, which had not been touched by the iconoclasm of 1566, churches were “cleansed” of idolatrous images, Reformed pastors were installed, and consistories were organized, sometimes in opposition to local magistrates who advocated a less stringently confessional reformation (Hibben 1983; Ten Boom 1987; see also Spaans 1989). Though the newly public Reformed Protestant congregations usually attracted only very small minorities of the local populations as full members, the experience of local church building and intercommunity networking “under the cross” gave them enormous advantages in the contest for local position, virtually assuring them the biggest churches and eventually a formal monopoly on public worship.[35] Yet the same organizational discipline and confessional rigor that strengthened them internally made it difficult for these essentially voluntary congregations to assume the role of a community church: zealous and aggressive consistories often kept local magistrates at arm’s length while the requirement of submitting to the spiritual discipline of the consistory appears to have made the transition to full membership in the worshiping community a comparatively difficult one for most people (Parker 1985; Duke 1990; Pettegree 1994). In each of these cases the local trajectory of the process of religious contestation went from repression (via sectarian confrontation) toward civil war and quickly veered toward exclusive reformations before reaching various forms of accommodation of sectarian difference.

By the mid-1570s, then, the basic geography of Reformed Protestant success had begun to take shape in the south and west of France and in the north of the Low Countries—that is, on the peripheries of the Valois and Habsburg regimes where rebels enjoyed their greatest military success. In these areas, the Huguenot and Beggar coalitions began to fashion revolutionary governments that consolidated their political power on a regional scale and served to underwrite still costlier and more destructive civil wars.[36] In the southern Netherlands, which had always been the heartland of popular support for Reformed Protestantism, there would be one more round of popular religious/political revolution. There, in the context of the Pacification of Ghent (1576),[37] locally variable Reformation coalitions once again seized the initiative in Brussels, Antwerp, and Ghent, forcing reluctant elite leaders to open up new opportunities for popular political action as well as religious choice (Decavele 1984; Marnef 1986, 1987, 1994, 1996). In Ghent, which had lost its chartered self-governance in 1540, a radical Reformed Protestant regime came to power in 1577, reasserted the city’s political independence, and in alliance with Holland and Zeeland anchored a significant pocket of rebellion in Flanders and Brabant until 1584. By the mid-1580s, however, the political/military tide had once again turned; in particular, the Walloon nobility had made a separate peace with the Spanish regime by the Treaty of Arras (1579), and with the urban rebels cut loose from their former allies, the Spanish were able to consolidate their reconquest of the southern provinces by attacking the towns one by one (Parker 1985). And by the same token the waves of popular evangelical mobilization, which had begun so dramatically and with great promise in the 1560s, had finally ended—either crushed by military failure or co-opted by the consolidation of elite leadership in rebel enclaves.