| • | • | • |

The Early Bengal Sultanate, 1342–ca. 1400

In 1258 Mongol armies under the command of Hülegü Khan sacked Baghdad and executed the reigning caliph, al-Musta‘sim, thereby formally extinguishing the ultimate font of Islamic political legitimacy. Nonetheless, for a half century after this disaster, coins struck in India continued to invoke the phrase “in the time of the caliph, al-Musta‘sim,” suggesting the inability of Indo-Muslim rulers to conceive of any legitimizing authority other than that stemming from the titular Abbasid caliph. But finally, in 1320, Qutb al-Din Mubarak, the Delhi sultan, broke from tradition and boldly declared himself to be the caliph of Islam. Although the title did not stick, and was in fact harshly received, the principle was now established that Islam could have multiple caliphs, and that they could reside even outside the Arab world. This revolution in Islamic political thinking occurred just about the time when Bengal again asserted its independence from the Delhi sultanate. In 1342 a powerful noble, Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah (1342–57), wrested Bengal free from Delhi’s grip and established the first of several dynasties that remained independent from North India for the next two and a half centuries. The break with Delhi was marked by a shift of the Ilyas Shahi capital from Lakhnauti, the provincial capital throughout the age of Delhi’s hegemony, to the new site of Pandua, located some twenty miles to the north.

Initially, Delhi did not allow Bengal’s assertions of independence to go unchallenged. In 1353 Sultan Firuz Tughluq took an enormous army down the Ganges to punish the breakaway kingdom. Although Firuz slew up to 180,000 Bengalis and even temporarily dislodged Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah from his capital at Pandua, he failed to reannex the delta. Six years later, Firuz made another attempt to restore the delta to Delhi’s authority, but he was again rebuffed, this time by Shams al-Din’s son and successor, Sikandar Shah (r. 1357–89).[28] These inconclusive invasions of Bengal, and the successful tactics of the two Bengali kings to elude the North Indian imperialists by fading into the interior, finally persuaded Firuz and his successors of the futility of trying to hold onto the distant province. After 1359 Bengal was left undisturbed by North Indian armies for nearly two centuries.

In reality, the emergence of the independent Ilyas Shahi dynasty represented the political expression of a long-present cultural autonomy. In the late thirteenth century, Marco Polo made mention of “Bangala,” a place he had apparently heard of from his Muslim informants, and which he understood as being a region distinct from India, for he described it as “tolerably close to India” and its people as “wretched Idolaters” who spoke “a peculiar language.”[29] Our first indigenous reference to “Bengal” appears in the mid fourteenth century, when the historian Shams-i Siraj ‘Afif referred to Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah (1342–57) as the “sultan of the Bengalis” and the “king of Bengal.”[30] The coins of this ruler, and the architecture of his son and successor, clearly reflect the new mood of independence. Shams al-Din’s coins are inscribed:

Here the sultan not only proclaims an association with the caliphate but lays claim to imperial glory, calling himself “the second Alexander.” Though perhaps not measuring up to the accomplishments of Alexander the Great, Shams al-Din certainly did a creditable job of “world-conquering” in the politically dense theater of fourteenth-century India: in addition to resisting repeated invasions from Delhi, he defeated a host of neighboring Hindu rajas, namely those of Champaran, Tirhut, Kathmandu, Jajnagar, and Kamrup (corresponding to modern Bihar, Nepal,Orissa, and Assam).

[Obverse]:The just sultan, Shams al-dunya va al-din, Abu’l Muzaffar, Ilyas Shah, the Sultan. [Reverse:] The second Alexander, the right hand of the caliphate, the defender (or helper) of the Commander of the Faithful.[31]

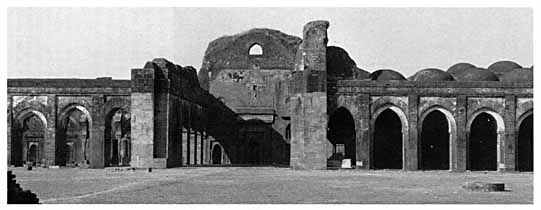

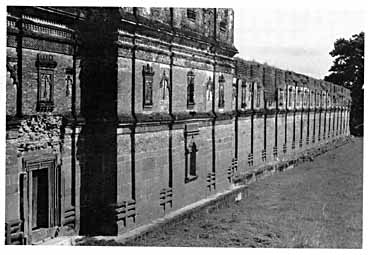

The most spectacular evidence of the dynasty’s imperial pretensions is seen in a single monument built by the founder’s son and successor, Sultan Sikandar (r. 1357–89). This is the famous Adina mosque, completed in 1375 in the Ilyas Shahi capital of Pandua (figs. 6 and 7). Although its builders reused a good deal of carved stone from pre-conquest monuments, the mosque does not appear to have been intended to convey a message of political subjugation to the region’s non-Muslims, who in any event would not have used the structure. In fact, stylistic motifs in the mosque’s prayer niches reveal the builders’ successful adaptation, and even appreciation, of late Pala-Sena art.[32] The imposing monument is also likely to have been a statement directed at Sikandar’s more distant Muslim audience, his former overlords in Delhi, now bitter rivals. Having successfully defended his kingdom from Sultan Firuz’s armies, Sikandar projected his claims of power and independence by erecting a monument greater in size than any edifice built by his North Indian rivals. Measuring 565 by 317 feet externally, and with an immense courtyard (445 by 168 feet) surrounded by a screen of arches and 370 domed bays, the Adina mosque easily surpassed Delhi’s Begumpur mosque, the principal mosque of Firuz Tughluq (1351–88), in size.[33] In fact, the Adina remains the largest mosque ever built in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 6. Interior of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Interior facing western wall, showing collapsed barrel vault. Photo by Catherine Asher.

Fig. 7. Exterior of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Exterior of western wall, showing fac^lade of barrel vault.

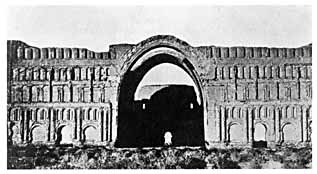

Fig. 8. Taq-i Kisra, Ctesiphon (near Baghdad, third century A.D.). Façade in the late nineteenth century. From Arthur Upham Pope, A Survey of Persian Art (Ashiya, Japan: Jay Glück, 1964), vol. 7, pl. 149. Reprinted by permission of Jay Glück.

Its style, moreover, signals a sharp break from the Delhi-based architectural tradition. The western, or Mecca-facing, side of the mosque projects a distinctly imperial mood, reminiscent of the grand style of pre-Islamic Iran.[34] This wall is a huge multistoried screen, whose exterior surfaces utilize alternating recesses and projections, both horizontally and vertically, to produce a shadowing effect. Whereas such a wall has no clear antecedent in Indo-Islamic architecture, it does recall the external façade of the famous Taq-i Kisra palace of Ctesiphon (third century A.D.), the most imposing architectural expression of Persian imperialism in Sasanian times (A.D. 225–641) (fig. 8). Even more revealing in this respect is the design of the mosque’s central nave. Whereas the sanctuary of the Tughluqs’ Begumpur mosque in Delhi was covered with a dome—a feature carried over, together with the four-iwan scheme, from Seljuq Iran (1037–1157) to India in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries[35]—that of the Adina mosque is covered with a barrel vault. Never before used on a monumental scale anywhere in India, this architectural device divided the whole structure into two halves, as did the great barrel vault of the Taq-i Kisra. The mosque thus departed decisively from Delhi’s architectural tradition, while drawing on the much earlier tradition of Sasanian Iran. We know that generations of Iranian architects and rulers had considered the Sasanian Taq-i Kisra palace to be the acme of visual grandiosity and splendor, and a model to be consciously imitated.[36] Thus Sikandar was at least an heir, if not a conscious imitator, of this tradition.

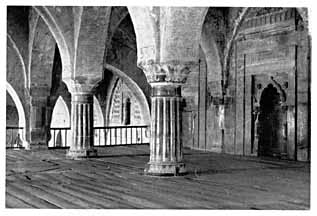

Fig. 9. Royal balcony of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Royal balcony, interior.

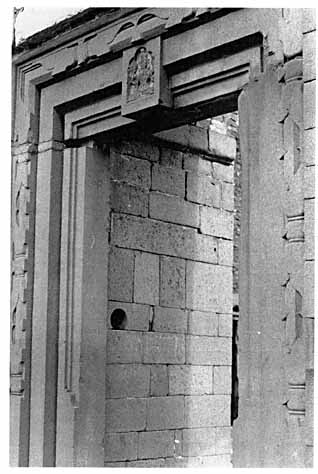

The interior of the Adina mosque also projects an aura of imperial majesty. To the immediate north of the central sanctuary is a raised platform, the so-called “king’s throne” (bādshāh kā takht), which enabled the sultan and his entourage to pray at a height elevated above the common people (fig. 9).[37] And, while the latter entered the mosque from a gate in the mosque’s southeast corner, the “king’s throne” could be reached only through a private entranceway that passed through the western wall. This entire doorway was evidently stripped from some pre-Muslim structure, as can be seen by the defaced Buddhist or Hindu image in its lintel (fig. 10). As if the mosque’s imperial architecture did not speak for itself, Sultan Sikandar ordered the following words inscribed on its western facade:

One word of praise for God, mentioned in passing, and the rest for the sultan!In the reign of the exalted Sultan, the wisest, the most just, the most liberal and most perfect of the Sultans of Arabia and Persia, who trust in the assistance of the Merciful Allah, Abul Mujahid Sikandar Shah the Sultan, son of Ilyas Shah, the Sultan. May his reign be perpetuated till the Day of Promise (Resurrection).[38]

Both the coinage and the architecture of the early Ilyas Shahi kings, then, indicate a strategy of political legitimization fundamentally different from that of their predecessors. Whereas the governors of thirteenth-century Bengal had merely transplanted Delhi’s architectural tradition to the delta, the sultans, having wrested their autonomy from Delhi, asserted their claims of legitimacy by placing state ideology alternately on pan-Islamic and imperial bases. If Sultan Sikandar’s architecture and Sultan Shams al-Din’s coinage reflect an imperial strategy of legitimation, we see the pan-Islamic approach in the latter’s claimed association with the caliph, and in the lavish patronage of the holiest shrines of Islam by Sikandar’s son and successor, Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah (r. 1389–1410), who sponsored the construction of Islamic colleges (madrasas) in both Mecca and Medina.[39]

Fig. 10. Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Lintel over royal doorway of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375)

Moreover, although the Bengal sultans continued to inscribe most of their monuments and coins in Arabic, from the mid fourteenth century on, they began articulating their claims to political authority in Perso-Islamic terms. They employed Persianized royal paraphernalia, adopted an elaborate court ceremony modeled on the Sasanian imperial tradition, employed a hierarchical bureaucracy, and promoted Islam as a state-sponsored religion, a point vividly and continuously revealed on state coinage. Foreign dignitaries who visited Pandua at its height in the early fifteenth century remarked on a court ceremony that we can recognize as distinctly Persian. “The dwelling of the King,” wrote a Ming Chinese ambassador in 1415,

Clearly dazzled by the ceremony of Pandua’s royal court, the ambassador continued: “Two men bearing silver staffs and with turbaned heads came to usher (us) in. When (we) had taken five steps forward (we) made salutation. On reaching the middle (of the hall) they halted and two other men with gold staffs led us forward with some ceremony as previously. The King having returned our salutations, kotowed before the Imperial Mandate, raised it to his head, then opened and read it. The imperial gifts were all spread out on carpets in the audience hall.” The ambassador was then treated to a sumptuous banquet, after which the sultan “bestowed on the envoys gold basins, gold girdles, gold flagons, and gold bowls.”[41] The peacock feathers, the umbrellas, the files of foot soldiers, the throne inlaid with precious stones, the lavish use of gold—all of these point unmistakably to the kind of paraphernalia typically associated with Perso-Islamic and even Sasanian royalty. Only the presence of elephants recalls the ceremony of traditional Indian courts.is all of bricks set in mortar, the flight of steps leading up to it is high and broad. The halls are flat-roofed and white-washed inside. The inner doors are of triple thickness and of nine panels. In the audience hall all the pillars are plated with brass ornamented with figures of flowers and animals, carved and polished. To the right and left are long verandahs on which were drawn up (on the occasion of our audience) over a thousand men in shining armour, and on horseback outside, filling the courtyard, were long ranks of (our) Chinese (soldiers) in shining helmets and coats of mail, with spears, swords, bows and arrows, looking martial and lusty. To the right and the left of the King were hundreds of peacock feather umbrellas and before the hall were some hundreds of soldiers mounted on elephants. The king sat cross-legged in the principal hall on a high throne inlaid with precious stones and a two-edged sword lay across his lap.[40]

Whether appealing to mainly Islamic symbols of authority, as was typically the case from 1213 to 1342, or to imperial Persian symbols of authority, as was typically the case from 1342 on, the Muslim ruling class sought the basis of its political legitimacy in symbols originating outside the area over which they ruled. No more were Bengal’s rulers, like the early governors, content with declaring themselves merely first among “kings of the East.” On the Adina mosque, Sultan Sikandar proclaimed that he was the most perfect among kings of Arabia and Persia, not even mentioning those of the Indian subcontinent, where he was actually ruling. In the same spirit his son and successor, Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah, tried without success to persuade Hafiz, the great poet of Shiraz, to come and adorn his court at Pandua.[42] The political and cultural referents of these kings lay, not in Delhi or Central Asia, but much further to the west—in Mecca, Medina, Shiraz, and ancient Ctesiphon.