| • | • | • |

The Imambargah as “Sacred Space”

Imambargahs in North America serve both to evoke Karbala and to publicly claim space by creating an Islamic presence in the midst of the alien “West.” Imambargahs are tied to Karbala as a sacred place by decorative symbols that draw one’s attention to God, the Prophet, and the Ahl al-bayt. When imambargahs are established in buildings originally designed for other purposes, only the interiors of these buildings are transformed into recognizably Islamic places.

On the other hand, when a community has the opportunity to build its own structure, it must decide to what extent the building will participate in a “Western” aesthetic. In the case of the Ja‘ffari Center, which was built in 1978, an architect was hired with explicit instructions to construct a recognizably Islamic building, and yet one lacking such characteristic features as domes and minarets, which might make it stand out too abruptly from the local architecture (cf. Haider, this volume). The completed building is a remarkable edifice, which is recognizably Islamic and yet part of the Canadian architectural landscape. It represents an Islamization of local architecture that mirrors other attempts by the community to find ways to Islamize the local environment—for example, using English in majlis. Imambargahs are therefore places where an indigenous North American Islamic aesthetic is being created.

The Ja‘ffari Center is situated amidst other religious edifices, including a Chinese Buddhist Temple and a Jewish synagogue—both of which provide extra parking for the center during Muharram. On its main level, the center contains a large hall for majlis, called the Zainabia Hall, and a masjid (mosque). Upstairs are a library and a large room for women with children. Women can participate in majlis from a large room located downstairs.

The centrality of spiritual history and allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt are clearly evident in the architecture and decoration of the building. The very names of the component parts of the structure evoke the presence of the Ahl al-bayt. For example, the majlis hall is named for Husain’s sister Zainab. This is significant, since the hall is used for the purpose of bearing witness to the events of Karbala just as Zainab, as a survivor of Karbala, bore witness to the generation of Muslims immediately following those events. A sign notes that the foundation stone was laid by Dr. Abdulaziz Sachedina on the day of Ghadir Khumm, which commemorates Muhammad’s designation of ‘Ali as his mawla, which may be considered the founding of Shi‘ism itself.

The importance of sacred names and words is evident throughout the building. The majlis hall is flanked on one wall by ten glassed-in arches. The rear wall contains four more—two each on either side of a large arch-shaped window—for a total of fourteen. When I first saw the structure in 1982, these arches held bare glass. Within the past few years, stained glass bearing the word “Allah” in Arabic script and one of the names of the fourteen masumin (those protected from error)—Muhammad, Fatima, and the twelve imams—has been installed at the top of each arch. This hall is laid out towards the qiblah (the direction facing Mecca). At the end of the hall closest to the qiblah, there is a large archway connected to a skylighted alcove, which forms an open boundary between the hall and the masjid.

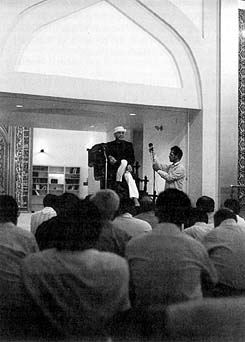

Recently, ornate pieces of Arabic calligraphy have been installed in the center. At the mihrab, there is a piece containing many of the ninety-nine names of God. In the hall itself, on either side of the archway leading to the masjid, there are two large pieces of calligraphy. One depicts the hadith in which the Prophet designated ‘Ali as his successor, the other a qur’anic verse reputed to refer to Husain. During the first ten days of Muharram, the zakir, or person who delivers the majlis, sits upon the minbar (a wooden staircase of about six or seven steps that serves as a pulpit near the qiblah) between these two signs of the Ahl al-bayt’s authority to deliver his majlis (fig. 34).

Figure 34. The majlis hall at the Ja‘ffari Center in Toronto, showing minbar flanked by calligraphy. Photograph by Vernon Schubel.

At one end of the hall, there is a room labeled zari, which contains replicas of the tombs of the imams (ta‘ziyahs) and other pictures and objects evocative of the Ahl al-bayt. There are also containers for making monetary offerings in the name of the imams, ‘Ali, or the Ahl al-bayt.

All these features serve to evoke the central paradigm of Shi‘i piety—allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt. The physical environment of the building continually draws one’s attention to the necessity of that allegiance by constantly evoking Karbala in both the spatial geometry and the decoration of the center. Karbala is thus always present within the imambargah. During the first ten days of Muharram, the presence of Karbala is intensified through the performance of devotional rituals.