| • | • | • |

The Fifohazana or Protestant Exorcists

Nearly all Protestant sects in Madagascar conduct exorcisms. Some have special curing retreats where exorcists work full-time; two of the mostactive groups are the Lutherans and the FJKM.[8] The exorcist movement and its associated specialists are referred to as fifohazana (HP: “awakening,” “revival”; from the verb mifoha, “to wake,” “to arise”); they are also called mpiandry (HP: “shepherds”). Since I am specifically interested in those activities that are related to spirit possession, I will refer to them here as exorcists. Satan (Satany) and devils (devoly) are thought to cause misfortune, and so the exorcist’s goal is to drive spirits out of the bodies of their victims. In general terms, individuals usually fall ill because they have no faith in Jesus (Jesosy).

Exorcists have received special training as healers and they form a special branch of their respectives churches. The majority are Malagasy, and they include pastors, evangelists, and parishioners. They are male and female, and they come from a wide variety of backgrounds, including peasants and educated professionals. Ethnic affiliation reflects the geographical distribution of Protestant missionary activities throughout the island: typically they are Merina and Betsileo from the highlands. There are also Antandroy, Antaisaka, and Antaimoro from the south and southeast and Tsimihety from the west and north. Rarely are they Sakalava or Antakarana. In Ambanja, several churches hold exorcism ceremonies on a regular basis. The FJKM church, which is by far the largest Protestant church in town, is most actively involved in this, and has more than a dozen trained specialists. Others include the Lutheran church and a small Pentecostal group that calls itself the Fifohazana Church, which broke off from the FJKM over a decade ago.

Exorcists gain inspiration and guidance from prophets, and each church has its own. According to FJKM records, the fifohazana movement was started in the 1880s by a Betsileo man from the high plateaux named Rainisoalambo. He was a diviner (mpisikidy) who suffered from severe and incurable skin problems. He had a dream in which he was told to go to the church, and so the next day he threw away his medicines (fanafody-gasy) and went there with his children. Eventually he built his own church in Soatanana, near Fianarantsoa, where he began to heal others. Soatanana is now a major center for fifohazana training and healing activities for numerous churches (Anonymous 1962; Rasamoela 1975; Trexler 1989). Although each church has its own prophets, the Lutherans pride themselves on having the only living prophet, who is named Nenilava (“Tall Mother”). Nenilava is Antaimoro and is the daughter of an herbalist (HP: ombiasy) who converted to Lutheranism when she was young. Her visions and wisdom concerning the teachings of Christ make her a central figure in her church (cf. Trexler 1989).

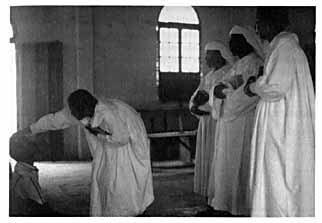

The style of dress and methods of healing are fairly standard among different Protestant groups. The clothes they wear during exorcism sessions reflect a blending of Calvinist dress of more than a hundred years ago, combined with high plateaux styles (see plate 8 and the last two photos in Estrade 1977). Exorcists always dress in white and keep their bodies well covered. Men generally wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants, and women wear long-sleeved blouses and ankle-length skirts. Both men and women sometimes wear long white robes that have puffy sleeves and dog-eared collars that are tied close to the throat. Some also wear bulky white shawls, reminiscent of the lamba worn by Merina. Many wear a wimple, wrapping a white cloth around their foreheads and then tying it at the back of the head. These clothes may be worn every day like a uniform or only during healing sessions. The quality and elaborateness of clothing often reflect the amount of church treasury funds available for exorcism activities.

8. Fifohazana exorcist driving spirits out of a patient while others watch and wait their turns. Note that the exorcist has placed her hand on the patient’s head.

The role of an exorcist can be a part- or full-time occupation. Some exorcists assist only during healing sessions that occur on Sundays after regular services, while for others it is a way of life, such as those who live in healing retreats (see below). The majority became exorcists after they or someone close to them was healed. Exorcists treat all forms of illness, including physical ailments such as blindness, headaches, lameness, troubled thoughts, restlessness, madness, and possession. Satan and devils cause illness and suffering, and the exorcist heals by driving them out of their victims through the laying on of hands (HP: fametra-han-tànana) and through prayer (vavaka). The exorcist’s strength and power are derived from the Holy Ghost (ny FanahyMasina) and for this reason Lutherans refer to exorcisms as asa sy fampaheresana (“work and empowerment”). Exorcists prefer to work in groups of three, reflecting the power of the trinity. Groups of other sizes are acceptable, but exorcists avoid working alone. As one put it, “When you work alone you may think that the power is in you, forgetting that it is derived from the Holy Spirit…if you are too proud you might fail in your work.” Exorcisms occur frequently in Ambanja: throughout 1987 I witnessed approximately a dozen, and I heard of more than twenty others. Five of the sessions I witnessed took place at the Lutheran church where I lived, where one of the pastors was trained as an exorcist.

The purpose of these healing sessions is to cure specific ills as well as to ensure general well-being in the congregation. Some churches schedule sessions on a regular basis, such as on the first Sunday of each month. Private, intensive sessions can be arranged for those who suffer from serious problems. Exorcists may apply their powers at home as well, treating themselves and members of their households, or they may be called into a patient’s home to work. Some patients come on their own, but most often they are accompanied by kin. The majority of patients are adolescent girls who are plagued by njarinintsy and other forms of possession sickness; older women (thirty or older) who wish to rid themselves of tromba spirits; and those whom kin label as mentally ill (adala). Serious problems can not be cured in one session but require a number of visits to ensure that the spirit(s) has left permanently. If the patient is not a Protestant she or he is also expected to convert and become a regular member of the church.

Exorcism as Therapy

Exorcism sessions are electrifying events that are exhausting for both exorcist and patient, and they can be frightening for young children and for the uninitiated. During these sessions a patient’s kin may also be present, as may parishioners, who have been encouraged to attend so that they may assist by praying and singing. Parishioner participation is necessary for several reasons. First, prayers and hymns are imbued with the power of the Word of God. Second, spirits enjoy music and so hymns help to draw them out of their victims. Third, by participating in these sessions parishioners are witnesses of God’s work.

Exorcisms have several stages. If the exorcists are not in their robes, they will don the proper attire before they begin (often this is done with great ceremony at the front of the church). All church services open with the singing of hymns, and this is also true for exorcisms. The session then proceeds with readings from the Bible and most often these include the following passages:[9]

Then he said to them: ‘Go forth to every part of the world, and proclaim the Good News to the whole creation. Those who believe it and receive baptism will find salvation; those who do not believe will be condemned. Faith will bring with it these miracles: believers will cast out devils in my name and speak in strange tongues; if they handle snakes or drink any deadly poison, they will come to no harm; and the sick on whom they lay their hands will recover.’

[10][Ary hoy Izy taminy: Mandehana any amin’izao tontolo izao hianareo, ka mitoria ny filazantsara amin’ny olombelona rehetra. Izay mino sy atao batisa no hovonjena; fa izay tsy mety mino no hohelohina. Ary izao famantarana izao no hanaraka izay mino: hamoaka demonia amin’ny anarako izy; hiteny amin’ny fiteny izay tsy mbola hainy izy; handray menarana izy; ary na dia misotro zava-mahafaty aza izy, dia tsy hampaninona azy izany; hametra-tànana amin’ny marary izy, dia ho sitrana ireny.]

Jesus repeated, ‘Peace be with you!’, and said, ‘As the Father sent me, so I send you.’ Then he breathed on them, saying, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit! If you forgive any man’s sins, they stand forgiven; if you pronounce them unforgiven, unforgiven they remain’

[Ary hoy indray Jesosy taminy: Fiadanana ho anareo; tahaka ny nanirahan’ny Ray Ahy no anirahako anareo kosa. Ary rehefa nilaza izany Izy, dia nanisy fofonaina, ka hoy Izy taminy: Raiso ny Fanahy Masina; na helok’iza na helok’iza no avelanareo, dia voavela izany; ary na an’iza na an’iza kosa no tsy avelanareo, dia tsy voavela izany.]

In addition to these passages, which speak of the laying on of hands and the healing powers of God, exorcists may read others that refer specifically to the problems of those who have come to be cured. These people are asked to form small groups at the front of the church and sit on the ground on a mat. Amid the singing, the exorcists lay their hands upon the heads of these people and pray quietly for their health and well-being. Patients with more serious problems are then called before the congregation and are healed separately.

The tenor of sessions directed at helping more serious cases is very different, especially when possession is the cause of the problem. During sessions for tromba possession, for example, the spirit is first reidentified as a demon or as Satan. The spirit must be encouraged to come forth so that it may then be driven from the body of its victim. These actions echo and draw from those of a tromba ceremony, where the spirit arrives by possessing the medium, announces its name, and converses with the audience. An exorcism, however, it not a joyful event but a frightening and volatile one because the spirit is quickly angered when confronted by the exorcists. If there are several exorcists present, they divide into groups (preferably into threes) and they work together with each patient; periodically they change places, rotating from one patient to another. In this way the intensity of the healing power directed at each person is great and is varied. As parishioners sing, the exorcists shout at the spirits in the imperative voice, a form that in most cases is used in Malagasy only to address naughty children, animals,[11] and demons: “Voka!” (“Get out!”), “Mivoka amin’ny ianarana Jesosy!” (“Get out in the name of Jesus!”).

As the exorcism progresses, the language becomes more powerful and the volume increases as exorcists shout their orders and parishioners sing louder and more intensely. This is usually when the spirit arrives. If it is a tromba, curses may suddenly issue forth from the mouth of the patient; if it is a njarinintsy, the victim will start to wail loudly, scream, and sob. Possessed patients usually collapse periodically on the ground, at which point the exorcist orders them to “get up!”(mifoha!). The exorcist speaks directly to the spirit, encouraging it to engage in a dialogue. He asks, “Who are you!? Why have you possessed this person!? What do you want?” and, in hearing the answers, he shouts back again, “Get out! get out you devil!” (Voka! Voka devoly!) or “Go back to the desert from whence you came!” (Handeha amin’ny tany karakaina!). These sessions can be violent, not only because the patient may fall or thrash about but because the exorcist, in wrestling with the spirit, may push at or tug on the patient’s body. Sometimes an exorcist repeatedly pushes a patient to the ground and then orders the patient to “get up! Rise up in the name of Jesus!”[12]

Eventually, the wailing will stop and the patient will regain consciousness, feeling exhausted. The hymns become quieter, and the session will end with a prayer to bless all who are present. This session will be followed by at least one more session, generally later that week, to ensure that the spirit has departed permanently. One unusual case that I witnessed involved three members of an Antandroy family (mother, father, and thirteen-year-old son). It was the mother who originally requested to have a tromba exorcised, but soon it was clear that the father, too, had a bilo spirit. Each time the father’s spirit was driven from him it would then move into the body of his wife or son, so that each person in turn had to have this spirit exorcised. This required several weeks of intensive work, involving six exorcists who worked with the patients two or three times each week.

Following these healing sessions, the exorcists, pastor, or congregation members visit patients in their homes to make sure they are well. If a patient had a tromba spirit, she will be instructed to bring all of the spirit’s paraphernalia to the church, so that it can be burned or otherwise destroyed. Patients are also expected to return to the church for Bible study and prayer and they are encouraged to join the church as permanent members.

Being an exorcist is difficult and involves great dedication. As one confided:

One of the problems in being an [exorcist] is that people here [in Ambanja] think I’m like a moasy [herbalist]—they want to be able to come just once, be cured, and leave. Maybe they think I am more powerful than most moasy but, still, I am the same to them. If they ask me to come to their house to help them, I always ask them if they use fanafody…that is our [the fifohazana’s] way. They may say no, but sometimes I think they are hiding that they do use it, because they are afraid to say yes. For us, we are not like the moasy, because we expect the person to become a member of the church,to choose to be Christian. It is no good if I come and exorcise them and then I don’t see them again.…I think some people think, “he is an exorcist, so why don’t we have him come and see what happens?”…One time a well-known woman here in town…had me come to her house.…I think her husband had a tromba [spirit], or maybe he is a little crazy [adala]?—but I am not sure. His wife had me come exorcise him—and I gave him a book to study, but they didn’t come to the church.…Being an exorcist is difficult—people will come to you at any time—sometimes in the middle of the night—because they are afraid and they ask if they can sleep here in our house. We take them in, we share their problems.…I am not as strong as they think I am, I have my faults, I sin, too, sometimes. But this is why I have chosen to be an [exorcist].

The Protestant Toby (Camps) or Curing Retreats

Several Protestant churches have centers for faith healing which are called toby (HP, lit. “camp”) and which I will refer to as “curing retreats.” The Lutherans are most famous for this, having established a large retreat in the high plateaux near Fianarantsoa. The mother church, which is located in a suburb of Antananarivo, also hosts regular healing sessions. In 1987 a new retreat was being built in the outskirts of this city so that there would be a second hospital that was more centrally located on the island. Many patients come to the Lutherans seeking the guidance of the Prophet Nenilava, who moves back and forth between the two centers. Smaller, usually rural retreats, can be found throughout the island.

Exorcists and their patients live full-time at these curing retreats. Primary curing activities involve the laying on of hands and intensive prayer sessions. Sometimes the kin of seriously ill patients will come and request that the exorcists accompany them home. A group of them (preferably three) will join the household temporarily to watch over and heal the sick person, and room and board is provided as payment for their services. Because the bonds that develop between the exorcists and the patient’s kin can be strong, sometimes an exorcist later marries someone from the patient’s household.

In northwest Madagascar, near Ambanja, there are three FJKM curing retreats. The closest was established in 1986 and lies eight kilometers from the town (and one kilometer off the main road). The work of these Protestant exorcists tends to be ecumenical in nature, reflected by the fact that although all those living at the retreat are members of the FJKM church, the deacon (HP: iraka), who moves between the threeretreats, is Anglican, as is the Antaimoro planter who donated the land. The FJKM church also has sought to combine efforts with other churches in order to establish an additional center in Ambanja.

The retreat near Ambanja occupies one-third of a small village, which has a total population of approximately two hundred people. It consists of a large open area about the size of a soccer field, surrounded by numerous structures, including an outdoor kitchen and shaded eating space; an unfinished (roofless) church; a long rectangular building that has four apartments in which the exorcists live; and three small, two-room houses that are for patients and their kin. The church is constructed of concrete. All other buildings are modest structures made from traveler’s palm.

Eight adult exorcists (four men and four women, including two married couples), and about a dozen children are the retreat’s full-time residents. At any given time there are three to five patients living there who are usually accompanied by one or two of their kin (such as parents, spouses, or siblings). The exorcists are Tsimehety, Betsileo, and Antaimoro, whereas the majority of the villagers are Sakalava as well as Antaimoro settlers. Patients are of diverse backgrounds and include fairly equal proportions of tera-tany and vahiny: when I visited in April 1987, they were Sakalava, Antakarana, and Tsimehety from the north; Comorean; and Antaimoro migrants from the south. Flanking the settlement on one side are fields, where the exorcists grow manioc, rice, maize, and greens. On the other are the villagers’ dwellings, a Catholic church, a schoolhouse, and a playing field.

Like the majority of their patients, exorcists are poor, yet therapy itself is free and thus practical, since they rely on the power of the Holy Spirit to heal. Exorcists live solely off donations and the bit of food they can eke out of the land. As is true for hospital care throughout Madagascar (and elsewhere in the Third World) patients are expected to cover all of their own expenses, so kin accompany them to make sure they have clean clothing and food to eat. The cost of a long-term stay at the retreat can create serious hardships. Such was the case for an elderly Antakarana couple who had been living at the retreat for six months so that their son could be treated for madness. As the father explained:

Here it is very hard for us, we have five other children…two, who live nearby, come to visit and bring us rice when they can. Here rice is very expensive, half again as much as it is in the market in Ambanja. I must work in other people’s coffee and cocoa fields for money, and my wife helps othersin their houses. We always need money to buy rice and other food, nivaquine [for malaria] and aspirin. Since there is no car that goes to Ambanja, it is very hard for us to travel to and from this village. We are not sure how much longer we can stay.

Most patients who come to this retreat are adults. They suffer from an assortment of problems. The majority (male and female) are mentally ill. The second largest group consists of single women who are suffering from tromba and other forms of possession. There are also those who are crippled (kalemy) and, finally, those with more general ailments, the most common being skin problems. When I visited the retreat outside Ambanja in April 1987, there were five patients there: two Sakalava women who suffered from tromba possession; a young Antaimoro boy, about age ten, who appeared to be mentally handicapped (as one exorcist said, “When he first came here he didn’t even know how to use silverware”); a Comorean man in his late thirties who was diagnosed as mentally ill (marary saina), who sat and talked to himself; and the young Antakarana man whose father is quoted above and who was also said to be mad. The majority of patients who come here have previously sought help from indigenous healers but found no cure. Some patients may stay for months, while others have remained for years.

Each exorcist is responsible for several patients, who in turn have three exorcists assigned to them. The treatments they administer take several forms. First, everyone is expected to pray (mivavaka) three times a day, since prayer weakens Satan. Second, laying on of hands (fametrahan-tànana) occurs twice a week. The notion of community is constantly stressed, and thus fictive kinship is a key defining principle for social relations among exorcists and patients. The pastor and deacon are referred to as “father” (papa or baba), and exorcists refer to each other as siblings, expecting patients and their kin to address them in this manner as well.[13] There is also a strong emphasis placed on the importance of work, and so patients labor in the kitchen, fields, and elsewhere according to their individual abilities and strengths. When one Sakalava villager was asked to describe the exorcists, she said “they work very, very hard” (miasa mafibe izy).

Three times a year the FJKM fifohazana exorcists hold reunions, and the location rotates between the three curing retreats in the northwest. One of my assistants went to observe a reunion during Pentecost, which lasted for two days. Much time was spent praying and singing hymns or working in the compound, and a communal feast was held wheremeat was served. This meal was a great luxury that the exorcists at this retreat could ill afford: since they receive little if any money from the mother church, their daily diet generally consists of a meager dish of boiled manioc and bananas, often with no rice. In all, 695 people attended. This official head count included the ten patients and their kin. The patients consisted of the five currently in residence at this retreat, plus five others who came from the two other retreats. These patients included three women who were suffering from tromba possession (see accounts of Vivienne, below, and Mona, who appears later in this chapter; also Appendix A); two men who were mentally ill (marary saina); and a woman with a child who had a severe case of diarrhea. The other participants consisted of seventy exorcists, other novices training to be exorcists, and congregation members, including those who had come for first communion.

Throughout the night the exorcists healed through the laying on of hands. Participants were split into two groups, so that the majority stayed outside while the ten patients were taken to be healed separately inside one of the houses. As one exorcist explained to my assistant, this was done because healing sessions can be upsetting to watch, since sometimes Satan can make patients act violently.

Seeking Cures for Possession: Three Case Studies

The stories that appear below all concern extreme cases. The first involves a woman who, like Victoria, suffered from problems that shifted between possession sickness and madness. The other two are women who refused to accept tromba mediumship as a permanent manifestation of their lives. Although all three of these patients are Sakalava, they each took a radical step in the therapeutic process, seeking assistance from non-Sakalava Protestants for their problems. Two of these women have chosen to convert, thus abandoning Sakalava culture for a new religious system.

Vivienne

Vivienne is from a family where many of the women are tromba mediums. Her older classificatory sister is an established medium who receives many clients in her home and who was one of my key informants (see Alice in Appendix A). Another classificatory sister is Berthine … (see above) who had her spirit exorcised by members of Modern Islam.

Vivienne is the daughter of a Sakalava mother and Tsimihety father. She is fifteen years old and she attends junior high school to the north in Ambilobe. She was raised by her mother, who was Catholic and who died when Vivienne was twelve. Her father lives in Diégo. Following her mother’s death he arranged for Vivienne to live with his brother and his brother’s wife, who are both members of the FJKM church. Throughout the summer Vivienne has been living with her aunt (MoSi) in Ambanja. Although her aunt is not Christian, she decided to bring Vivienne to the Pentecostal retreat that my assistant attended.

For one year Vivienne has been very sick, troubled by a njarinintsy spirit. As her aunt explained: “Sometime she is crazy [adala izy é]!…If I ask her to set the table, she puts spoons under the tablecloth; at other times she cooks with hair!…She swears [vetaveta] and she has tried to hit her uncle! Now she lives with me.…Sometimes she cries and laughs suddenly—this even happened when she was at school! I took her to the Catholic priest and he told me to take her to the Lutherans [around the corner]. We went there one Sunday, but nothing happened. So then I took her to the FJKM church. Her father’s relatives want her to come and stay here [at the retreat], but Vivienne refuses, saying that she is Catholic and that she has no intention of changing her religion.”

Vivienne and her aunt later returned to the retreat, where they lived for four weeks. Here Vivienne took part in healing and prayer sessions several times each day. After two weeks she felt stronger (hery) (and, as her aunt and the exorcists noted, she had also become more cooperative) and she started to work in the fields. Three months later she returned to school. Vivienne occasionally attends Sunday services at the FJKM church. When her Sakalava friends tease her about this, she states flatly that she goes for her health and she insists that she has not converted.

I later asked one of the Lutheran exorcists about Vivienne, who stressed that, in his opinion, she was not possessed, but was mad (marary saina):

She doesn’t look at you when you talk, but she gazes around and talks to herself. That is not like someone with njarinintsy. I remember I asked her if there was anything troubling her and she said yes, that there was a boy who had tried to harm her with fanafody—he pretended that he loved her and sweet talked her, but she later realized he didn’t care about her at all. This is so common!…With these young girls it is always a problem with a boy. I told her to forget about it, that there were better ones out there. I tried to heal her and to help her, stressing that she must come back with her family—I am not a doctor, I can not cure someone in just one session! But she never came back. I think that she must have gone to the FJKM church because she has relatives who pray there. This is better, because her kin will be there with her and, besides, their work is the same as mine. They know how to heal the same way as I do.

Elisabeth

Elisabeth is forty-two years old and the daughter of Sakalava parents. She was raised in a small village northwest of Ambanja. When she was very young (five years old) she had already begun to show signs of tromba possession, and by the age of seven her parents had held a ceremony to instate a fairly powerful Child spirit within her. Neighbors were skeptical of this development, finding it difficult to believe that a girl so young could have a tromba spirit; nevertheless, she soon had clients who came from other villages and towns seeking her spirit’s advice. By the age of fifteen she had two other spirits, a Child and a Zafin’i’fotsy Grandparent.[14] As Elisabeth put it, mediumship was a very difficult (sarotra be) experience. For much of her childhood she fell sick periodically, suffering from chronic weakness, dizziness and fainting spells, terrible headaches, and frequent nightmares.

At age seventeen Elisabeth convinced her parents to let her go live with her sister in Ambanja. She had previously visited the town on many occasions, preferring it to the sleepy village in which she grew up. In Ambanja she took her first lover who eventually became a common-law spouse. This relationship lasted for three years. She later met her husband, Claude, with whom she lived on and off for twelve years. Eventually she grew tired of this relationship. As she put it, all Claude wanted was the money she earned as a medium. As in her childhood, she frequently fell ill and sometimes was unable to get out of bed for weeks at a time. This made it extremely difficult for her to carry water, go to market, or care for her two children, especially when her husband was not with her. Twice spirit mediums had diagnosed her tromba spirits as the cause, and by the age of thirty-five she had held the appropriate ceremonies to have two additional spirits instated. Each time her health only improved temporarily. She also spent much time and money seeking help from other local healers and doctors, all to no avail. Repeatedly she was told by friends and kin that her spirits were responsible for her bouts of illness, and she had become frustrated nearly to the point of panic. Unable to earn enough money to host additional ceremonies to appease her spirits, her health only worsened.

In 1984, Elisabeth’s sister took her on the ferry to the nearby island of Nosy Be, where they sought out the Protestant exorcists at the FJKM church there. After several weeks of intense healing sessions (three times a week for four weeks), Elisabeth was finally freed from her spirits. Like the majority of mediums, she did not recall what took place during these interactions between her spirits and the exorcists, but she described the process as frightening and exhausting (mavozo aho,kajobe aho), followed by a sense of elation after each session. She has since converted to this church, and is now among their most highly respected exorcists. She lives in Nosy Be, two blocks from the pastor’s house. She has not, however, visited with her kin since this time. Only her sister comes to see her, since others, especially her parents, are ashamed that Elisabeth keeps the company of Merina Protestants.

Zaloky

Zaloky is approximately fifty years old (although, as described in chapter 2, she is easily mistaken for a woman who is much older). Zaloky’s life as a medium is fairly typical for older Sakalava tera-tany women. She wasmarried at age sixteen and, at age thirty-two, after the births of three of her four children, she became possessed by the transitional Child spirit Zaman’i’Bao(see chapter 5). Within two years she had become a respected healer in the area and she had a steady flow of clients. At age thirty-five her husband died. She describes the next five years as difficult and bitter ones because of struggles with her children over land rights (again, see her story in chapter 2). She eventually married (by common law) her second husband Marcel, a Tsimihety migrant laborer who had been a regular client of hers when seeking guidance from Zaman’i’Bao for problems related to work or physical ailments.

Zaloky describes her past activities as a medium as very difficult: “Zaman’i’Bao is a very powerful spirit, and his mediums must be strong [mahery]. It was a difficult life: I had many [clients]! too many! [bemaro! beloatra!]…they would come whenever they wanted, it didn’t matter how I was feeling.…You know, Zaman’i’Bao, he is hard on his mediums, he spits up blood.…Some days I would not be able to get up after a session [with a client]…my back and neck would be so sore; one day I saw black spots for three days! It was terrible…when a tromba spirit gets angry, he makes you sick.…I didn’t have the money to host a ceremony to make him happy, and this really frightened me. I wondered, is he going to kill me?…Marcel, who had gone to the FJKM church as a child, told me to go there to have the spirit driven out, but I didn’t want to. I was so afraid! [mavozo é!]. We live near the newly built Lutheran church, and my spirit didn’t like that either. They would start to sing and I could hear them in my house. I’d get scared, because sometimes Zaman’i’Bao would arrive suddenly and be very angry, especially when they sang the hymn “Jesosy Tomponay” [“Jesus our Master”].…Then one day I just wandered into the church, [possessed by] the tromba [spirit]! Can you imagine! I don’t remember what happened, but Marcel and the pastor say they stopped the service right there and drove out the spirit.…that was ten years ago.…Now Marcel and I pray there every week.…They take care of me; they are my family [HP: fianakaviana].” Zaloky is now a respected elder in the church. She and Marcel have fallen into economic hardship within the last few years and they continue to be troubled by land disputes with her children. The Lutherans give them food and she in turn has decided to will her land to this church (unless a disco next door overruns her homestead first).

Vivienne, Elisabeth, and Zaloky have each suffered from a form of possession which is fairly typical for Sakalava women their respective ages. Vivienne is an adolescent troubled by problems of love and romance, and she suffers from njarinintsy possession. Elisabeth and Zaloky were established mediums for Child and Grandparent spirits that commonly appear among women of their backgrounds and ages. All three are also unusual, however, and even marginal, in other ways. Vivienne’s problems with possession are extreme, now bordering on madness. Elisabeth’s career as a medium began at an exceptionally early age. Rather than accepting her fate, she has suffered terribly throughout her life, unable to cope with her status as a spirit medium. Regardless of her actions, she continued to be plagued by illnesses caused by her tromba spirits. For Zaloky, an older woman, the more mundane forms of suffering associated with mediumship eventually were intolerable. Although she had many clients, trance exhausted her and she found demands of visitors to her house to be too great. This was compounded by the terrible conflicts with her children over land rights.

These three women present extreme cases for yet another reason: although they are tera-tany, they eventually sought solutions through a nonindigenous institution dominated by peoples from the high plateaux. In the case of Vivienne, the Protestant exorcists may be able to help her through a serious illness—whether it is possession sickness or madness—coaxing it to leave and then giving her continued support. Elisabeth and Zaloky, on the other hand, are women who have rejected the role of tromba medium, choosing instead to be freed permanently from possession. They have come to the exorcists hoping to have their spirits driven from them because they find the suffering they experience as mediums unbearable. This is a pattern that has emerged in the Lutheran church, where, in addition to Zaloky, two other Sakalava have joined for reasons associated with tromba. The first is an old man (in his sixties) who, like Zaloky, had a tromba spirit exorcised and who later joined the congregation. He and Zaloky felt their ties to the local community were fragmented: Zaloky was embroiled in a bitter quarrel with her children over land inheritance, and this older man was unmarried and had no children. Another Sakalava convert was a twenty-year-old man who joined because he was deeply distressed by the suffering that he saw his mother and ex-wife endure as tromba mediums.

Seeking the assistance of the exorcists reflects a deliberate choice to opt out of and thus be free from the institution of spirit possession, which in many ways epitomizes what it means to be Sakalava. This involves embracing, at least in part, Protestantism as a new faith, either by drawing on the power of the exorcists for convenience’s sake to drive out unwanted tromba spirits, or through the more permanent act of conversion. In choosing this route, however, one becomes, in a sense, less Sakalava, not only because one rejects tromba, but also because Sakalava look disfavorably upon Protestant vahiny. As the stories of these three women show, this choice may also mark a shift away from kin and Sakalava identity: two of these former mediums have chosen to become members of new Christian communities that in many ways are like newly found kin.