| • | • | • |

Living in Mangaldihi

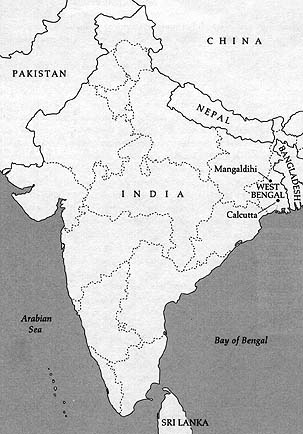

Most of what I report here describes people of modest means and middle or higher Hindu caste residing in the center of the village of Mangaldihi, where I lived for a year and a half from 1989 to 1990. Mangaldihi is located in West Bengal, India, about 150 kilometers from Calcutta, where I had previously lived and studied language in 1985 and 1986 (see map). The village of some 1,700 residents and 335 households comprised seventeen different Hindu caste (or jāti) groups, one neighborhood of Muslims, and one neighborhood of tribal Santals.[21]

India.

Brahmans were recognized as being the village’s “dominant” caste, as measured by landholdings, political clout, social mores, and the history of the village. Oral traditions told that Mangaldihi had been founded about 250 years earlier by Brahmans carrying figures of the deities Syamcand and Madan Gapal—forms of Krishna—from Brindaban far to the east, to protect them from Muslim invaders. Brahmans still lived in the village’s central neighborhoods, and the village’s major religious festivals still revolved around their ancient Vaishnavite deities. Brahmans also owned the majority of the village’s land (60 percent), although their landholdings had significantly decreased over the past several decades under a series of government land reforms.[22] Most of the village’s Brahman families still supported themselves by farming (rice was the staple crop), but only a handful of families owned more than ten acres of land. Most supplemented their agricultural income by finding salaried jobs in nearby cities and towns, working as priests, or opening small village grocery, tea, and video shops.

Numerically, the Brahmans in Mangaldihi were just about matched by the Bagdis, a lower or Scheduled Caste group occupying several village neighborhoods.[23] The Bagdis were much poorer than the Brahmans, owning an average of just a bit more than half an acre of land per household. They supported themselves mainly by working in Brahman households, tilling Brahman land, fishing, and cultivating small plots of their own. Bagdi representatives always secured several seats on the local panchāyat (government representative system), though, and they had a strong cultural and political presence in the village. Tables 1 to 3 list the other jāti groups of Mangaldihi, their traditional and current occupations, and size of their landholdings. Although most in the village did have enough to eat, very few were wealthy, and many families had to struggle to get by. There was a general feeling of scarcity and want in the village, which clearly seeped into the ways people structured and experienced their family relationships, their processes of aging, and the kinds of jealousy and bonds of maya, affection, and love that I describe in the following pages.

| Jāti Name | Number of Households | Traditional Occupation | Occupation in Mangaldihi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagdi[*] | 95 | Agricultural laborer,fisher | Agricultural laborer, fisher, servant, cow tender |

| Brahman | 84 | Priest | Landowner, priest, salaried job, shopkeeper |

| Santal | 34 | Tribal | Agricultural laborer |

| Musalman (Muslim) | 23 | Cultivator | Owner cultivator, agricultural laborer, shopkeeper |

| Muci[*] (or Bayen) | 22 | Leatherworker, musician, drummer | Agricultural laborer, musician, drummer |

| Kulu | 15 | Oil presser | Owner cultivator, shopkeeper, salaried job |

| Bauri[*] | 14 | Agricultural laborer | Agricultural laborer |

| Kora | 14 | Tribal | Agricultural laborer |

| Baisnab (or Bairagya) | 10 | Religious mendicant | Owner cultivator, shopkeeper,salaried job |

| Barui | 6 | Betel nut cultivator | Owner cultivator, shopkeeper, salaried job |

| Dhoba[*] | 3 | Washerman | Washerman, owner cultivator |

| Hari[*] | 3 | Midwife, drummer | Agricultural laborer |

| Napit | 3 | Barber | Barber, owner cultivator |

| Bene | 2 | Merchant | Shopkeeper,salaried job, landowner |

| Suri[*] | 2 | Liquor maker | Shopkeeper, liquor maker, owner cultivator |

| Dhatri[*] | 1 | Midwife | Agricultural laborer |

| Karmakar[*] | 1 | Blacksmith | Blacksmith, owner cultivator |

| Sadgop | 1 | Cultivator | Owner cultivator |

| Sutradhar | 1 | Carpenter | Carpenter, owner cultivator |

| KEY: * Jātis classified by the government as Scheduled Caste.

* Jātis classified by the government as Scheduled Caste.

Agricultural laborer Those who cultivate the land of others but own no (or very little) land of their own (see also table 3) Owner cultivator Those who own and cultivate their own land. Landowner Those who own land but do not cultivate it themselves. | |||

| Size of Holding (acres) | Number of Households | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Landless | 115 | ||

| < 1 | 83 | ||

| 1-5 | 87 | ||

| 5-10 | 39 | ||

| 10-15 | 7 | ||

| 15-20 | 4 | ||

| > 20 | 0 |

| Jāti Name | Number of Households | Total Land Held (in acres) | Average Landholding (acres per household) | Percent of total Village Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brahman | 84 | 406 | 4.8 | 58.4 |

| Kulu | 15 | 69 | 4.6 | 9.9 |

| Musalman | 23 | 56 | 2.4 | 8.1 |

| Bagdi | 95 | 53 | 0.6 | 7.6 |

| Barui | 6 | 36 | 6.0 | 5.2 |

| Baisnab | 10 | 13 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Bene | 2 | 12 | 6.0 | 1.7 |

| Suri | 2 | 12 | 6.0 | 1.7 |

| Muci | 22 | 11 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Sadgop | 1 | 7 | 7.0 | 1.0 |

| Napit | 3 | 6 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Dhoba | 3 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| Santal | 34 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Kora | 14 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Bauri | 14 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Karmakar | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Sutradhar | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Dhatri | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hari | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

It was in a Brahman neighborhood that I settled, in the mud hut—nearly abandoned—of a wealthy Brahman family who had since moved to an adjacent three-story brick house. They later invited me to move into an upstairs room of that house. So it was almost inevitable that I became closest to the village’s Brahman community, and it is their voices that figure in the following pages most saliently. I also spent a good deal of time in Bagdi neighborhoods, and I strove to interact with and gather data from members of each of Mangaldihi’s other caste and ethnic groups. I often found a high degree of variation in the ways the different castes or jātis of Mangaldihi practiced and perceived matters of gender and aging, distinctions that I highlight when especially relevant.

My research focused on older women and men. I often found them hanging out at temples, on roadsides, and in the courtyards of their homes, relatively free from the work that so engrossed most of their younger adult kin. We spent hours together talking about life, family relations and struggles, fears and hopes surrounding death, memories of childhood and romance, current television dramas, the problems of poverty, the sufferings of women, and the changing nature of modern society. I sought out men as much as I did women, for “gender” (one of the problems I was most interested in) must, I believe, include women and men. Indeed, gender studies done in South Asia have generally been weakened by the relative dearth of attention paid to men. In the field of gender studies, “gender” has been used largely as a code for “women.” [24] Women and men are equally gendered beings, however, and neither can be understood in isolation from the other and from the broader social worlds in which gender identities are constituted.

One of my main aims in hanging out with these older women and men in Mangaldihi was to gain a sense of their voices, lived worlds, and everyday experiences. Lawrence Cohen (1998) has written a fascinating, masterful account of constructions of old age and senility among families and institutions in the Indian city of Varanasi, and more generally in India’s gerontological and popular cultural texts. Perhaps partly because he is focusing on senility, Cohen largely omits old people’s own voices and experiences. (Senile, or in Varanasi parlance “weak-brained” or “hot-minded,” old people are presumably elusive informants.) I have taken Mangaldihi’s older people themselves as key subjects, as I have scrutinized how they envisioned, practiced, and experienced their own aging, embodiment, family relationships, grapplings with love and maya, and everyday lives in the world.

But since I myself was a younger woman, recently married, in my late twenties and early thirties, I also spent a good deal of time with my “peers,” younger unmarried and recently married women. My closest daily companion was Hena, a young woman in her mid-twenties who married during my time in Mangaldihi. She shared a room and single pillow with me every night until her marriage, telling me of village gossip, her concerns and dreams, and her own visions of older people. Neighborhood girls and boys also crowded into my room daily, sharing tea and snacks with me; and the younger wives in the neighborhood, when they could free themselves from work, would also make some time for me—as we perhaps bathed together, or took a trip to town to buy a sari, or stopped to make a cup of tea in the still afternoon while others were taking their naps.

I also learned a great deal from these younger people, which highlighted for me the ambiguities, multiple perspectives, and shifting meanings inherent in what it is to be a woman, a man, and a person in this community of West Bengal. I concentrate here on these competing, ambiguous perspectives, and especially on the ways in which the women and men I knew made and remade their social worlds and gendered identities as they moved through the latter phases of their lives.

Although I went to India and Mangaldihi to seek out their stories in the pursuit of writing a dissertation and then a book, many of these older people also sought me out as a listener. They called to me as I passed, climbed the three flights of stairs to my home, or tapped me on my arm, saying “You haven’t taped my life story yet,” “You must write this down,” “Did you get that in your notebook?” I hope that the following pages are true to their trust in me to articulate my sense of their experiences, and understandings, of their own lives and the lives of their neighbors.