Introduction

Tuberculosis is back. In most developed nations, a steady decline throughout most of the twentieth century reversed itself beginning in the mid-1980s, and cases of the disease have increased ever since. New bacterial strains resistant to various antituberculosis drugs have caused considerable alarm in major cities, where tuberculosis is often associated with AIDS, drug abuse, homelessness, and poverty. Meanwhile, in less developed countries, where tuberculosis never left the scene, it continues apace. Experts offer dire warnings of “the greatest health disaster since the bubonic plague”[1]; World Health Organization officials estimate that three million people worldwide die of tuberculosis every year and that fully one-third of the world’s population is infected with the tubercle bacillus.[2] The increased incidence has been paralleled by increased public attention, as each week brings new press reports of epidemiological studies and antituberculosis strategies.

France is no exception; recently, legislation has been introduced to revive that country’s antituberculosis dispensaries. Recourse to such an old-fashioned institution, thought by most to be “outmoded,”[3] suggests that the latest biomedical techniques can neither explain nor solve the problem of chronic illness in society. Indeed, the story of tuberculosis in France provides a revealing glimpse into the history of this problem. Or perhaps stories of tuberculosis would be more accurate. Cauldron of wealth and poverty, reform and revolution, social anxiety and scientific hubris, nineteenth-century France was the stage for several parallel dramas in which tuberculosis played key roles. French medicine, struggling to maintain its international preeminence, contributed crucial discoveries regarding the nature of the disease and oversaw the birth of germ theory. Intensifying worry over France’s low birthrate and stagnating population contributed to increased concern over the nation’s leading cause of death. Industrialization and urbanization radically altered the rhythms and material conditions of life. An ambitious, nationalistic bourgeoisie largely committed to economic liberalism finally assumed political power and debated how best to hold onto it. Meanwhile, a disastrous war with Prussia and the threat of class warfare made all of these issues more pressing during the early decades of the Third Republic. These and other stories will serve as the backdrop for this examination of tuberculosis as a social problem.

The comeback of tuberculosis confounds the familiar history of medicine’s incremental advances and triumphs. More than a century after the bacterial agent of tuberculosis was discovered and nearly half a century after the advent of effective antibiotic treatments, some very old questions are being asked about the disease, including, what is it about society that facilitates the spread of tuberculosis, and what can be done about it? These same questions were being asked with great urgency a century ago, and despite the vast technological and scientific changes of the intervening years, the answers most commonly proposed today bear a striking resemblance to the answers of the past. They range from a reliance on greater governmental intervention in public health matters (such as heightened surveillance by local authorities of those infected or “at risk”) to forced isolation of active cases.[4] A few scattered voices target poverty as the chief cause of tuberculosis and call for improvements in standards of living as the only means of effectively combating the disease.[5] The questions and the answers seem to be preserved intact from the first time tuberculosis emerged as a major social problem in many countries in the nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, since the mid-1980s, the AIDS crisis has forced increasingly technocratic, medicalized, welfare-state societies to confront the basic question of how and why a culture assigns particular meanings—especially moral meanings—to disease. Scientific knowledge, it has become clear, does not provide a single and exclusive “truth” about health and disease, and the clash of conflicting truths can be as traumatic (in a cultural sense) as any epidemic.[6] Although they certainly do not impose a definitive reading on the past, present-day struggles to address the social meaning of AIDS and tuberculosis add relevance and urgency to an examination of the history of such efforts. Before considering the factors that came to bear on the understanding of tuberculosis in the unique circumstances of nineteenth-century France, it is worth briefly discussing the basic characteristics of that elusive pathological entity—characteristics that, if not timeless or absolute, at least correspond to the current consensus in medical science.

Tuberculosis is a contagious disease. That simple fact is both indisputable and misleading. The causal agent of tuberculosis—variously known as the Koch bacillus (after Robert Koch, the German bacteriologist who first identified it in 1882), the tubercle bacillus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis—is a bacterium transmitted from person to person most often through inhalation of “aerosolized” sputum droplets expelled through coughing. In the majority of cases, the infection is localized as a lesion in the respiratory tract and contained by immune reactions, never producing symptoms of illness (although it does, for example, cause a positive reaction to a skin test). When resistance is compromised for any reason, at the time of infection or at any subsequent time, the bacilli can spread and attack the body’s tissue. This “active” or “open” tuberculosis occurs most often in the lungs but can also affect the lymphatic glands (scrofula), bones, intestines, brain, liver, kidneys, and other organs. Nonpulmonary forms of tuberculosis can also be acquired by ingesting milk or meat from infected cows. This form of transmission was the object of a certain amount of concern in the nineteenth century, before widespread pasteurization of milk and regulation of meat supplies, but it was always perceived as a minor danger compared to inhalation.[7] (Pulmonary tuberculosis is by far the most common form of the disease. Both in the nineteenth-century sources and in these pages, the word “tuberculosis” indicates primarily the pulmonary localization, although in prophylaxis, as opposed to diagnosis or treatment, there was often little practical distinction to be made among the various forms.)

The recent resurgence of tuberculosis in the United States and other industrialized countries has taken place among certain clearly identifiable communities and “risk groups”: homeless people, drug addicts, prison inmates, poor immigrants, migrant farm workers, the elderly, and people with HIV infection and AIDS.[8] All of these groups share one common trait: immunodeficiency, the central element in the acronyms “HIV” and “AIDS.” Most of them share another closely related trait: poverty, with all of its concomitant physical effects. This present-day epidemiology, so divergent at first glance from the observed and reported incidence of tuberculosis in nineteenth-century societies, may at least provide some questions (if not answers) with which to address the historical dimension of tuberculosis.

In both present and past societies in which tuberculosis is prevalent, far more people are infected with (that is, exposed to) the bacillus than ever experience symptoms. A still smaller subset of the population dies of the disease. Even at the historical peaks of the disease’s incidence, the seemingly vast numbers of deaths from tuberculosis each year represented just a fraction of those infected. Indeed, it is possible that a near-totality of the population of many large European cities in the nineteenth century technically “had” tuberculosis—that is, would have tested positive for exposure to the tubercle bacillus.[9] It is widely believed today that in the United States, only 10 percent of those infected with the disease ever develop active or “symptomatic” tuberculosis; in other words, even those who test positive for exposure (and therefore have Mycobacterium tuberculosis in their bodies) have only a one-in-ten chance of ever “getting” tuberculosis (becoming ill). This ratio is a widely quoted rule of thumb,[10] although there is evidence that this “risk of disease” (as opposed to “risk of infection”) varies considerably and is often much lower than 10 percent. Detailed long-term studies of certain populations have shown (1) that the risk of disease among those infected with tuberculosis drops off considerably after the first one to two years, and (2) that even as long as ten years following infection, the risk of developing active disease is often considerably less than one in ten, with rates varying between 0.6 and 3.7 percent in U.S. studies and reaching as high as 9.4 percent in others.[11]

It is impossible to know whether these proportions hold true for other geographic and historical contexts; yet even if the precise figures differ, there is reason to suppose that in many industrial cities a century ago, nearly the entire population was infected with tuberculosis.[12] In late-nineteenth-century Le Havre and Paris, when the disease was at its deadliest and accounted for one-fifth to one-fourth of all deaths, it killed only a fraction of those infected. It follows, therefore, that all or nearly all of those cities’ residents were infected with the tubercle bacillus by the time they reached adulthood. Most people lived their entire lives without any inkling of their infection. Exposure does not equal illness. However, any circumstance that compromises the body’s resistance by depressing immune reaction can cause latent tuberculosis infections to reactivate, no matter how long ago the original exposure took place. Today, such circumstances range from malnutrition, drug abuse, and alcoholism to cancer (especially following chemotherapy) and AIDS.[13]

It is certain that similar immunosuppressive factors were at work in nineteenth-century France. Particularly among the working classes, where tuberculosis claimed most of its victims, the obstacles to maintaining a decent standard of living were formidable. The influence of any individual factor on the incidence of tuberculosis at the time is impossible to determine. It is not the aim of this book to develop a retrospective epidemiology of tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France, even if such a project were feasible. The primary sources for such an endeavor—even statistical reports and surveys—are so thoroughly imbued with the categories, preconceptions, and concerns of the time that to wrench them from this context would rob them of all meaning. Even to condemn them as “biased” would be to suggest misleadingly that they could have been otherwise. Juxtaposing the medical and public health texts of the nineteenth century with present-day judgments regarding the true causes or incidence of disease borders on reproaching the doctors and authorities of the time for not knowing then what is known now, an enterprise of little historiographical value. It is quite another matter, however, to examine orthodox or mainstream knowledge in light of conflicting views that were being expressed on the same issues at the same time. This book undertakes to trace what was known about tuberculosis in the nineteenth century, the conditions under which that knowledge was produced, and how it was used.

A recent historiographical controversy has resuscitated the question of the “true” causes of tuberculosis in the nineteenth century. This debate illustrates the difficulties and uncertainties inherent in historical epidemiology as well as the implications of such scholarly questions for present-day tuberculosis control efforts. The exhaustive and pioneering work of Thomas McKeown in Britain had over several decades—in the view of most historians—established that the decline of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases in the industrial world was largely a result of rising standards of living rather than medical advances or state intervention in matters of public health.[14] This revisionist thesis opened up new horizons of scholarly inquiry, but it also stepped on some toes. In the past few years, a strong backlash against McKeown has emerged. A series of articles has attacked the standard-of-living thesis and argued that the real reasons for the decline of tuberculosis in France, Britain, and the United States can be found in government sanitary reforms and in the isolation of those suffering from the disease.[15]

Allan Mitchell, an expert in the history of France’s relations with and attitudes toward Germany, has contended that the public powers’ inaction in the face of tuberculosis explains France’s relatively high death rate from the disease around the turn of the century. France lagged behind, the argument goes, while its neighbors in Britain and Germany pursued concerted campaigns to improve public health. Therefore, tuberculosis rates declined in both of the latter countries—but not in France—during the decades leading up to World War I.[16] Actually, the experience of the three major western European powers at the close of the nineteenth century can be read quite differently. The available evidence, in fact, clearly indicates (1) that tuberculosis mortality was declining in France, albeit more slowly than in Britain and Germany, and (2) that France’s higher death rate and slower decline in tuberculosis corresponded to a standard of living that was lower and improving more slowly than that of the other two countries.[17]

It is difficult to establish with any certainty the curve of tuberculosis mortality over the course of the nineteenth century in France. Nationwide statistics were not kept on such matters until after the First World War; even for large cities, the figures date back only as far as 1887. However, Paris was under a microscope for most of the century, and the occasional publication of tuberculosis death rates for the capital begins in 1816. Calculating per capita and combining the early Paris numbers with the later figures for all of urban France, it is possible to approximate the direction, if not the overall magnitude, of the disease’s incidence.

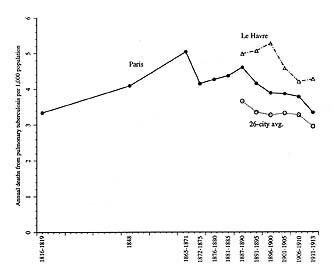

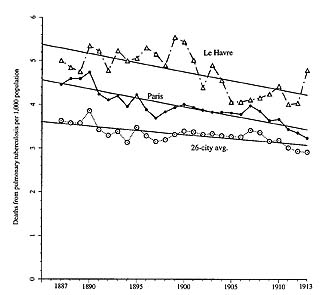

According to this method, tuberculosis increased gradually in France until its peak in the late 1880s and early 1890s, whereupon it decreased, also gradually, through most of the twentieth century. Figure 1 depicts tuberculosis mortality for Paris over the entire nineteenth century, alongside Le Havre (France’s tuberculosis leader) and an aggregate of the twenty-six largest French cities for the Belle Epoque, averaged out over census periods to give a more reliable long-term picture.[18] Figures 2 and 3 focus on periods of particular interest. One apparent anomaly is a dramatic increase in Paris in 1870 and 1871, during the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent siege of Paris; Figure 2, with annual figures not averaged out over census intervals, shows its magnitude and suddenness. Figure 3, also showing year-by-year changes, suggests that although statistics for cities other than Paris were kept only beginning in 1887, the overall peak of tuberculosis mortality in urban France may have come around 1890, give or take five years; outside of 1870–1871, the long-term experience of Paris bears this out. The decline of tuberculosis was long and gradual; by the time vaccination and effective medication were made widely available in the 1950s, most of the historical decline in the industrialized nations had already occurred.[19]

1. Annual tuberculosis mortality in Paris and other French cities, 1816-1913.

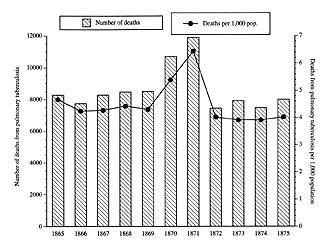

2. Tuberculosis mortality in Paris, 1865-1875.

3. Tuberculosis mortality in Paris and other French cities, 1887-1913, with lines showing closest-fitting equations for long-term trends.

A closer look at the sudden surge of tuberculosis mortality during the Franco-Prussian War and siege may also shed some light on the McKeown debate. After averaging 8,250 deaths per year from pulmonary tuberculosis between 1865 and 1869, Paris suddenly saw this figure balloon to 10,691 in 1870 and 11,900 in 1871 before falling back to a mere 7,436 in 1872. The per capita tuberculosis mortality rose from a prewar average of 4.38 per thousand per year to 5.38 and 6.44 before settling back to 4.01 in 1872—a nearly 50 percent rise within two years, followed by a decline just as precipitous in a single year.[20] Such drastic yearly fluctuations in tuberculosis death rates were unknown in France both before and after this episode; there is only one plausible explanation for this sudden rise and fall. The overriding facts of material life in Paris during the siege of 1870–1871 were the Prussian blockade and the ensuing food shortage. Only the severe hunger and impoverishment that resulted can conceivably explain the sudden rise (and equally sudden fall) in tuberculosis mortality in these years. Likewise, on a less dramatic scale, the early Third Republic as a whole appears to have been a time of slowly but noticeably improving standards of living in France. For example, the best estimate of real wage growth (synthesizing the work of four respected economic historians) shows a 33 percent increase between 1882 and 1909—from wages in 1882 that had only recently rebounded from levels far below that of 1824.[21] Slowly but appreciably declining death rates from tuberculosis beginning in the early 1890s may be related to this trend.

Much more difficult to explain is the puzzling shift in sexual inequality where tuberculosis was concerned. In Paris, until around 1860, more women than men died of the disease; thereafter, the differential was reversed. Moreover, the proportions were significant: in the 1830s, for example, nearly two-thirds more women than men succumbed to tuberculosis, whereas by 1890, it claimed almost two-thirds more men than women.[22] For the later period, other French cities showed a sex differential similar to that of Paris. On the rare occasions when early-nineteenth-century doctors and “hygienists”[23] referred to the overrepresentation of women among victims of tuberculosis, they attributed it variously to women’s inherent weakness, to the constricting effect of corsets on the chest, or to workplace conditions specific to certain predominantly female occupations.[24] Later, around the turn of the century, authorities failed to point out that the sex differential had reversed itself, but they did use the higher mortality among men to bolster the contention that alcoholism (thought to be a predominantly male affliction) contributed to tuberculosis. (See chap. 5, below.)

Alain Cottereau, one of the few historians to point out this shift, attributes it to two trends. Without citing any evidence, he claims that improving conditions of childbirth lessened the susceptibility of women to tuberculosis. Meanwhile, he argues, accelerating industrial capitalism, with its debilitating physical labor affecting a mostly male workforce, weakened the resistance of men to infection.[25] There may be validity in Cottereau’s argument, as well as in the alcoholism thesis. However, far more detailed research is needed before this significant historical change can be satisfactorily explained by these or any other factors. Whatever the case, the sizable and changing sex differentials in tuberculosis mortality cannot be explained by the late-nineteenth-century emphasis on unsanitary housing and on exposure to the bacillus among the causes of the disease, since the sexes could not have been subject to these factors to an appreciably different extent.

Every attempt to single out the determinant factor or factors in the incidence of tuberculosis in the nineteenth century must inevitably run up against the only indisputable fact that emerges from all the available evidence: the lives of many tuberculosis victims were lived inside a constellation of social conditions that affected their overall well-being. These conditions included debilitating, draining labor; little or no job security; meager wages; poor diets; slum housing; filthy bodies and surroundings; and heavy drinking. It seems obvious in retrospect that these conditions were interrelated, even inseparable. Any attempt to extract from this constellation a single social cause of tuberculosis is doomed to failure, or at best to irrelevance, because it presupposes that one or more of these conditions could have operated independently of the others.

Most historians have chosen to avoid speculating on the “true” causes of tuberculosis, with Mitchell and Cottereau among the exceptions. By and large, however, even when they have averted such pitfalls, histories of tuberculosis—in France and elsewhere—have operated within an unfortunately narrow and limiting conceptual framework. The historiography has tended to downplay politics, ideology, and contestation, orienting itself instead toward medical triumphalism and consensus, with the romantic allure of “consumption” occasionally given attention as well. While these have become somewhat shopworn complaints among historians of medicine, and they no longer apply to much of the field, they unfortunately characterize much of the work on the history of tuberculosis in the past twenty years.[26] Especially for the period after the rise of germ theory, conflict and opposition within the medical profession regarding the causes and prevention of disease recede from the historiographical picture. This is regrettable and misleading; in fact, one can find a great deal of tumult, strife, and uncertainty in the archival and published sources relating to tuberculosis.

A recent spate of works has drawn increased scholarly attention to the history of tuberculosis. Since 1988, two books on Great Britain, three on the United States, one on France, and one covering both Europe and the United States have appeared, in addition to two others on France published in the mid-1980s—all specifically dealing with tuberculosis.[27] These works send mixed signals about the fate of the old triumph-and-consensus model. Pierre Guillaume’s Du désespoir au salut: Les tuberculeux aux 19e et 20e siècles is a useful survey with some valuable insights. However, its title, From Despair to Salvation, sends a naively positivist message that simply does not correspond to the history of tuberculosis. Guillaume pays homage to the “intrepid practitioners” and “obstinate men of science” and “men and women of good will” who “led a…victorious combat” against the disease.[28] As noted above, to attribute the decline of tuberculosis to “men of science” is a dubious enterprise at best. Guillaume’s book dwells at length on the existential suffering of the sanatorium patient in the twentieth century (and gives considerable attention to the romantic literary sensibility), while passing over the social dimension of the disease relatively quickly. One is left with the impression of an emotional and spiritual affliction, devoid of social or political significance.

Two students of Roland Barthes, Isabelle Grellet and Caroline Kruse, are also fascinated with the twentieth-century world of the sanatorium, but they reject medical triumphalism. Their Histoires de la tuberculose: Les fièvres de l’âme contains brilliant insights, particularly concerning the surveillance impulse in medical thought and the invisible power of multiple, intertwined stigmas woven around a disease. Grellet and Kruse proudly proclaim their method of mixing up genres within their source material, reading literary, medical, and autobiographical “discourses” “pell-mell.”[29] Indeed, the range of material from which the authors coax information and interpretation is their strong suit. However, in their eagerness to transcend artificial intellectual barriers, they ignore the importance of the genres themselves. In the words of the historian Joan Scott, interdisciplinary analysis should “take seriously the boundaries of disciplines and the different genres they represent but make these a matter for investigation, rather than a set of preconditions for scholarly work.”[30]

Alongside the continuing interest in the spiritual and literary significance of tuberculosis and the attempts to discover a true historical epidemiology, there seems to be a sustained effort to tell the empirical story of various societies’ responses to the disease. For example, Linda Bryder’s Below the Magic Mountain revives the debates and the politics behind medical treatment and state antituberculosis intervention in early-twentieth-century Britain. Similarly, several of the essays in Peurs et terreurs face à la contagion, a 1988 collection organized by the French Society for Historical Demography, exemplify a critical and historically sensitive attitude toward the ostensibly neutral domain of medical knowledge. The essay by Dominique Dessertine and Olivier Faure on sanatorium policy in the interwar years shows the degree to which the “sanatorial network,” instead of being a set of strictly therapeutic institutions, involved elements of a repressive, carceral strategy. Didier Nourrisson’s contribution to the volume retraces the vagaries of the official French dogma concerning alcoholism’s role in tuberculosis during the years surrounding the First World War. His identification of the interests at stake in national alcohol policy and the social imperatives behind official orthodoxy testifies to both a critical temperament and a careful attention to primary texts and subtexts.[31]

Perhaps the most exciting and promising trend in the historiography of health and disease over the last fifteen years—a trend that has informed my approach to the history of tuberculosis—is best exemplified by the work of William Coleman and Richard Evans. Both of these historians have highlighted the myriad interrelationships—some obvious, some quite subtle—between political economy and public health practices. Coleman’s Death Is a Social Disease inserts the early-nineteenth-century hygienic investigations of Louis-René Villermé and his colleagues into the context of liberalism and nascent socialism outside of which they are incomprehensible. Coleman acutely depicts the dilemma in which Villermé, one of the pioneers in the study of public health in France, found himself: compelled to point out appalling social inequality but incapable of recommending remedial public action. Evans’s Death in Hamburg examines the 1892 cholera epidemic—and indeed the material life of an entire city—against the backdrop of a society dominated by a merchant elite dedicated to the principles of laissez-faire.[32]

Many of the variables that governed society’s understanding of and response to tuberculosis were material ones. Yet there were also less concrete forces at work, forces that operated through language and systems of thought and that deserve equal attention. Many scholars, inspired by the work of Michel Foucault and other theorists, have tried to pry apart “discourses” and expose the politics behind “objective” scientific knowledge. At its best, this effort remains attuned to empirical and material modes of explanation as well. One exemplar of this approach, David Armstrong, has looked for the “political anatomy of the body” in twentieth-century British public health policies. Among his findings of particular relevance to this study is the “dispensary gaze,” a strategy of controlling space within the city by mapping the movement of pathology within it.[33] Ways of seeing combine with other material and ideological imperatives to constitute responses to disease. As Allan Brandt has put it, “Medicine is not just affected by social, economic, and political variables—it is embedded in them.”[34] In a sense, this is both the premise and conclusion of all social history of medicine, including this book.

The “truth” about tuberculosis changed drastically in France over the course of the nineteenth century. Around 1820, during the Bourbon Restoration, consumption, or phthisis, was an individual, inscrutable, and all but random killer, probably hereditary and somehow related to passion. In the 1830s, under the July Monarchy, the disease was for the first time seen as socially discriminating, choosing its victims from certain professions and from poor neighborhoods. Beginning in the 1840s, being a consumptive woman signified in certain circles heightened sensibility and emotion as well as the redemptive power of suffering. From the late 1860s through the early 1880s, as the Third Republic established itself, the disease was possibly contagious. Around 1900, tuberculosis was a national scourge, highly contagious, lurking around every corner and symptomatic of moral decay. These successive truths, or stages of knowledge, about tuberculosis do not just show the developing content of medical science. They also reveal the changing social context within which that knowledge was embedded. It is the fit of content into context—and the changes that each wrought in the other—that will be examined here.

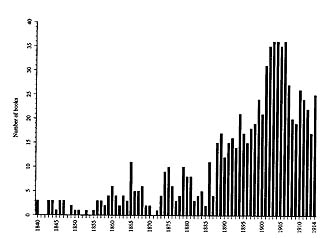

For a disease that throughout the nineteenth century was the leading cause of death in France, the chronology of official concern and mobilization is surprisingly limited. While the pace of medical work on the social aspects of tuberculosis accelerated after Jean-Antoine Villemin’s 1865 experiments on transmissibility and again after Koch’s 1882 identification of the tubercle bacillus, it was not until the late 1890s—after death rates from the disease had begun to fall in French cities—that governmental and philanthropic organizations began to mount what they called la lutte contre la tuberculose. (I have translated this as “the War on Tuberculosis,” a proper noun, to suggest the extent to which it was referred to as a formal institution or event, regardless of its actual impact. In this respect, its twentieth-century counterparts in the United States might be the War on Poverty and the War on Drugs.) Ten years later, much of the public and private energy behind the campaign had waned, and it was only after World War I that the battle was reengaged, this time in a very different form. The timing of the campaign is significant, in that it coincided neither with significant medical discoveries nor with any upturn in the incidence of tuberculosis. The magnitude of attention as measured by the printed word follows roughly the same curve. More than thirty-five books on tuberculosis were published per year between 1902 and 1906 in France, as compared to just four in 1887 and around fifteen per year in the early 1890s. The figure dropped off to just over twenty books per year on the eve of World War I.[35] (See fig. 4.) Despite its brief duration, the turn-of-the-century War on Tuberculosis represents a revealing episode in French social and cultural history, whose roots and legacy extend far beyond its short life span.

4. Number of books on tuberculosis published per year in France, 1840-1914.

Several milestones can be looked to for indications of France’s developing public concern about tuberculosis. Each of them generated considerable paperwork, discussion, and headlines—in the lay press as well as in medical journals. The first major salvo in the War on Tuberculosis was fired in the Academy of Medicine in 1898. The eminent physician Joseph Grancher delivered a lengthy report on behalf of an academy committee charged with proposing preventive measures against the disease. Grancher lamented the fact that tuberculosis had previously been discussed without any thought at self-defense on the part of a society armed only with “passivity and indifference.” He singled out one target for the thrust of his attack: contagious spittle. “The danger of contagion,” he wrote, “is underestimated every day, even by doctors. Far from the terror that it should inspire, tuberculosis is…accepted with resignation in families that take no precautions whatsoever.” It was not medical knowledge that was lacking, according to Grancher; it was the will to turn that knowledge into action.

Here is one of the central logical operations guiding the War on Tuberculosis: the tubercle bacillus is transmitted most often through spitting; therefore, our strategy must focus on discouraging spitting and on disinfecting spittle. Grancher, like nearly all his colleagues, saw exposure and bacilli as the vital point of attack. An important corollary was that people with tuberculosis were “dangerous.”We know…that the tuberculeux who spits or secretes his bacilli is dangerous and that we must be protected from him.…Bacillus-laden spittle…is the usual vehicle of the germ of tuberculosis! Therefore, that [spittle] is what we must destroy—right away—before it dries .…[36]

The following year, in 1899, Prime Minister René Waldeck-Rousseau appointed a blue-ribbon panel to investigate preventive policies against tuberculosis. The group, chaired by France’s leading hygienist, Paul Brouardel, returned in 1900 with a detailed study of mortality from tuberculosis and a set of recommendations that focused on population density and alcoholism, in addition to spitting, in the social etiology of the disease.[37] (Although it is a scientific term not in common usage, the word etiology will figure prominently in these pages, for lack of a convenient alternative. It denotes the body of knowledge and opinion concerning the causes of a given disease; its usage here generally refers to social causes.) In 1901, the government named a “permanent” tuberculosis commission that would meet periodically for the next decade, issuing reports on nearly every imaginable aspect of the disease’s place in public policy and making occasional practical recommendations to the bureaucracy. The commission’s members included well-known doctors, government functionaries, and politicians—including Léon Bourgeois and Jules Siegfried, two of the Third Republic’s most influential figures in the area of social welfare reform.[38]

In that same year, 1901, another landmark report also sounded a call to arms. This time, the audience was the French parliament, whose committee on public health took the legislature’s first public stand on the tuberculosis problem. Written by Deputy Lionel Amodru, the parliamentary report contained a full statement of what was by then the dominant etiology of tuberculosis—the official consensus of the medical community and public officials regarding the principal social causes of the disease. The dominant etiology isolated three key factors in the spread of tuberculosis: widespread exposure to the bacillus (in which spitting was the main culprit), slum housing, and immoderation (especially in drink).

Amodru’s report noted that tuberculosis claimed most of its victims among those between the ages of twenty and forty-five, adults “in the period of full activity,” that is, in the most productive sector of the workforce. “In these conditions,” he wrote, “tuberculosis can no longer be regarded simply as an accidental by-product of contemporary society.”

Amodru rehearsed what was becoming a familiar litany of enemies. Contagion meant that in modern city life one was never safe from tuberculosis. At work, at home, or at play, “if he is well, his companions are a danger to him; if he is sick, he is dangerous to them.” Like Grancher, Amodru contended that because spittle, le crachat, could contain the bacillus, “it is therefore the enemy” (c’est donc lui qui est l’ennemi). Even healthy citizens should aid in the effort to eliminate spitting by setting an example and refraining from a practice “as contrary to hygiene as it is to decorum.”[40]It is a fearsome, advancing scourge that is gaining ground every day with no obstacles in its contagious path; one is justified in saying that in France, where the population is not growing, [tuberculosis] is more than a threat to individuals—it is truly a national peril.[39]

In the aggressive rhetoric of antituberculosis education, if spitting was the “single greatest cause” of the disease’s spread, it appears to have shared that distinction with alcoholism and housing. Amodru’s report to parliament claimed that “of all the intervening causes of the illness, none is more formidable nor more frequently observed at the present time than alcoholism.…But it is above all unsanitary housing, lacking air and sunlight, that is the great auxiliary of tuberculosis.” Hyperbole aside, these were the two other social factors (along with contagion) consistently denounced by the official antituberculosis campaign. Amodru quoted Professor Louis Landouzy of the Paris Faculty of Medicine, noted authority on tuberculosis and source of numerous such aphorisms, to the effect that “alcoholism makes the bed for tuberculosis.” Brouardel, also from the Paris medical faculty, was Amodru’s source for material on housing:

This transition, too, from “slum housing is bad for one’s health” to “slum residents’ ignorance of hygiene is dangerous,” typified the dominant etiology and the War on Tuberculosis. At the same time, parliament was considering a bill—eventually passed into law in 1902—that mandated municipal health departments and generally increased both the capacity and the obligation of local authorities to keep the health of their populations under close surveillance.“If somebody,” writes Professor Brouardel, “predisposed by birth or by habits to tuberculosis, lives in…housing where air and sunlight penetrate abundantly, he can escape from contagion. Conversely, if a vigorous man, with no hereditary or acquired taint, lives in unsanitary housing, he will not escape contagion.…” One has to have seen in Paris certain poor workers’ housing to understand the extent to which hygiene can be misunderstood.[41]

After these developments, tuberculosis had become inscribed as one of the burning issues of the day in the French polity and in public awareness. The last major milestone in this progression was the 1905 International Tuberculosis Congress at the Grand Palais in Paris. During the week in October that the congress was in session and for several months before and after, tuberculosis was front-page news in Paris and the provinces, and controversies that otherwise would never have left the medical world were the subject of nationwide debate. For example, when a German doctor announced that he had discovered a substance that might be effective as either a vaccine or a cure for tuberculosis, the intense press coverage that ensued bore all the marks of a political scandal or a true-crime detective story. During the congress itself, crowds thronged the public lectures and exhibits concerning tuberculosis and its prevention. Several police brigades and a cordon of Republican Guards were needed to control the crowd of “curious” onlookers at the official opening of the congress. More than three thousand official participants, not including invited guests, vied for places in the two-thousand-seat auditorium of the Grand Palais.[42] For a short time, the eyes of the international medical community were on Paris, and the eyes of France were on tuberculosis.

After 1906, the intensity of public attention to tuberculosis subsided somewhat, reviving periodically when new legislative or philanthropic initiatives were launched. With the outbreak of World War I, the entire political, social, and administrative climate changed radically. Laws sponsored by Bourgeois in 1916 and André Honnorat in 1919 began the process of covering the nation with networks of antituberculosis dispensaries and sanatoriums, respectively. This process, along with the leading role taken by American philanthropy (through the Rockefeller Foundation) in postwar campaigns against tuberculosis, signaled a new phase in French society’s response to the disease.[43]

The zenith of the nineteenth-century War on Tuberculosis, then, lasted only from the late 1890s to around 1906. Why these years? There was no sudden upsurge in the incidence of tuberculosis at this time, nor were there any major medical discoveries about the disease. The timing of official worry points to reasons beyond epidemiology and medicine. The middle of the so-called Belle Epoque was a time that Susanna Barrows has artfully termed “the apogee of anxiety and anomie” in France.[44] The republic, its legitimacy consolidated since the late 1870s, was coming under increasing attack from both Left and Right. Gen. Georges Boulanger nearly engineered a coup d’état in 1889, and in the late 1890s, the Dreyfus Affair split the nation, pitting church, army, and tradition against secularism, modernity, and individual rights. Meanwhile, the amnesty of exiled Communards in 1880 and the legalization of labor unions in 1884 laid the groundwork for a revived workers’ movement. Strike-related protests and violence at Anzin, Decazeville, Fourmies, and Carmaux between 1884 and 1892 crystallized in many bourgeois minds the threat posed by a savage working class to private property and public order; a series of anarchist bombings culminating with the assassination of President Sadi Carnot in 1894 reinforced the immediacy of this perceived threat. A new wave of strikes beginning in 1904 and the formation of a unified Socialist party in 1905 intensified mutual class resentment and fear.

Other equally acute anxieties were also at work in France at the turn of the century. The economic, military, and biological vitality of the nation itself appeared to be threatened by dangerous trends to which its neighbors seemed immune. The German and British populations (and therefore their pools of potential workers and soldiers) were increasing rapidly. Meanwhile, France’s birthrate was low and falling fast, and the other side of the demographic equation was no more encouraging. Europe’s leading cause of death, tuberculosis, claimed far more lives per capita in French cities than in German or British ones, where it was also declining more rapidly. When French scientists took a close look at the French population during this period, they saw these trends as well as, in Robert Nye’s words, “a host of social pathologies that appeared to call into question both the quantity and the quality of the French population.”

According to Nye, such anxieties crystallized in “the literary generation of 1890” and gained strength through 1900. They most often involved an implicit or explicit comparison with Germany, the upstart power that had humiliated France in 1870.[46]Under the spur of the internal and external events of the era, a medical model of cultural crisis developed that exercised a linguistic and conceptual imperialism over all other ways of viewing the nation’s plight. If this model of crisis was medical in nature, it served the thoroughly cultural aim of explaining to the French the origins of national decadence and the weaknesses of their population.[45]

It is true, of course, that much of French history has been marked by anxiety and contentiousness; the entire nineteenth century in particular, with cataclysmic industrialization, urbanization, and revolutions, fits this description quite well. Yet the fin de siècle period was unique in several respects. The domestic and international political context of the period gave added intensity to concerns about France’s fragile status among nations. Both the perception and the reality of demographic decline added a new dimension to social fears that had been expressed in biological terms since the early nineteenth century.[47] Later, after 1906, the relative waning of public attention to tuberculosis coincided with rising international tensions and concerns over the imminent threat of war.[48]

French responses to tuberculosis cannot be understood outside of this political and cultural context. Birthrates, mortality, moral decay, political subversion, the filth and danger represented by the working classes in bourgeois eyes—tuberculosis allowed all these diverse and threatening themes to be assembled into a single coherent package. To be sure, the illness was not just a metaphor, not just a sign through which social relations or anxieties expressed themselves. Real people got sick and died from tuberculosis, just as they are getting sick and dying today. That seemingly self-evident proposition must not be forgotten. However, neither should that truth mislead historians into a fruitless search for the single true explanation of those real deaths. Even if much more historical evidence were available regarding the incidence and causes of tuberculosis, it would still represent the inescapable biases, preoccupations, and blind spots of the society in which it was produced.

All scientific knowledge is—and has always been—conditioned by social factors. Industrialization, urbanization, class conflict, religious piety and charity, bourgeois sexual morality, demographic stagnation, military defeat, and international rivalry all contributed to the peculiar shape of the French understanding of tuberculosis. In turn, worry over the nineteenth century’s leading cause of death inevitably colored perceptions of these and other aspects of French politics, culture, and society, lending an air of vital, bodily urgency and scientific certainty to discussions of problems outside the immediate realm of medicine. Ultimately, to write the history of tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France, one must write a history of nineteenth-century French society.

This particular social history, like all others, has biases and blind spots of its own. Recently, many social historians of medicine have trained their sights on the history of health care “from the bottom up.” They have resurrected the patient as a salient actor in the series of negotiations and complex interactions that constitute the history of healers and hospitals.[49] A great deal of information has come to light regarding the impressively varied sorts of medical care (both “traditional” and “scientific,” with a great deal in between) to which different segments of society had recourse in various epochs of history.[50] This has not been my approach here. Epidemiology and public health figure more prominently in this study than medical practice per se. In medical terms, this is a history of etiology and prophylaxis rather than of therapeutics. Conceptions of the causes and prevention of tuberculosis are my chief concern here, insofar as they provide keys to the vital question, how does a society make sense of a widespread and deadly disease? As a result of this preoccupation, the saga of medications and treatment regimens in the nineteenth century is given short shrift, as is that of the sanatorium (largely the province of the elite, particularly during the period covered by this study), and the voice of the individual patient is rarely heard. While stories of the doctor-patient interaction and of hospitals and other medical institutions do reveal important aspects of social change, they are peripheral to this account of how the healthy (in medicine, government, and elsewhere) explained tuberculosis to each other and to the not-yet-sick in the rest of society. Similarly, much of this study concerns the writings, teachings, and actions of influential men or committed propagandists; how the general population received their ideas must necessarily remain an open question. No simple method exists for determining the nature and extent of popular attitudes toward tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France. There are, however, scattered bits of evidence suggesting varying degrees of public receptivity to the agendas of medicine, government, philanthropy, and labor where tuberculosis was concerned. This evidence is considered carefully here, but the resulting picture of popular perceptions is, unfortunately, a partial one at best.

The first two chapters of this book cover the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century, when “essentialist” explanations of tuberculosis predominated. Chapter 1 examines the early social and epidemiological investigations of Villermé and other hygienists during the July Monarchy in the context of bourgeois concern over the rapid growth of cities (especially Paris) and the resulting poverty and social dislocation. It also discusses the controversy surrounding Villemin’s 1865 experiments purporting to show the transmissibility of tuberculosis and takes seriously the arguments of the since-discredited anticontagionists. Chapter 2 suggests that during these same pre-germ theory years, outside the realm of medicine, a certain age-old ideal of womanhood took a distinctive nineteenth-century form, appropriating tuberculosis as a vehicle of redemptive suffering. This ideal survived both the decline of romanticism and the Pasteurians’ demystification of disease and manifested itself at the end of the century in the strange and fascinating career of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux.

Chapters 3 through 5, the heart of the book, detail the development of the dominant etiology in the late nineteenth century and its implementation in the War on Tuberculosis. Chapter 3 explains how fear of microbes led doctors and public officials to mount a concerted campaign against spitting (except in approved, disinfectant spittoons) and fostered a certain “tuberculophobia” among the population, as infected people were discriminated against or even shunned. Disgust at the deplorable state of working-class slum lodgings prompted an unprecedented surveillance effort (notably in Paris and Le Havre), the casier sanitaire des maisons, which kept track of all buildings and apartment units whose occupants died of tuberculosis, so as to track down hotbeds of infection. Chapter 4 analyzes this administrative strategy as well as the role of women as vectors in what was diagnosed as the dangerous domestic spread of tuberculosis. Chapter 5 traces the way in which, by medically associating alcoholism and syphilis with tuberculosis, doctors and hygienists were able to link deviant behavior and marginal classes with the perceived moral and demographic decline of the French nation.

Chapter 6 focuses on the experience of Le Havre, which experienced tremendous urban growth as well as France’s highest tuberculosis mortality during the nineteenth century. What makes this Norman seaport a particularly salient case study is the convergence of these dramatically changing material conditions with the maturation of an activist group of city fathers led by the mayor (and occasional cabinet minister), Jules Siegfried. The city’s paternalistic bourgeoisie attempted to translate its fervent positivism into action, mobilizing on the local level to fight the scourges of slum housing, alcoholism, and tuberculosis—all perceived as serious threats to Le Havre’s prosperity. Among other examples, the story of France’s first municipal health department (established in 1879) testifies to the energetic (if unsuccessful) efforts directed against tuberculosis by an emerging cadre of hygienists, bureaucrats, and politicians.

Chapter 7 describes at length the origins and elaboration of a defiantly oppositional body of medical knowledge, which arose on the far left of French politics around the turn of the century. While some socialists sought to represent a working-class point of view within the terms of debate of mainstream medicine, doctors and other militants associated with revolutionary syndicalism rejected those terms of debate. They put forward a theory of tuberculosis based on diminished bodily resistance rather than on exposure to the bacillus (which they considered to be all but universal) and blamed overwork and low wages as the chief reasons for workers’ susceptibility to the disease. In the workers’ movement as in nearly every sector of French society, the turn of the century was a critical period of change, instability, and anxiety. Questions of power, identity, and survival increasingly focused on the leading killer of the time, at once familiar and mysterious. Throughout France, whether in medicine, politics, literature, or theology, knowledge of tuberculosis became valuable—and contested—terrain.

Notes

1. Unnamed “spokesmen for the World Health Organization,” quoted by William H. McNeill in his review of Frank Ryan, The Forgotten Plague: How the Battle Against Tuberculosis Was Won—and Lost (New York: Little, Brown, 1993), in Washington Post Book World, June 6, 1993, 1.

2. P. Sudre, G. ten Dam, and A. Kochi, “Tuberculosis: A Global Overview of the Situation Today,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 70 (1992): 149–159.

3. Michèle Biétry, “Tuberculose: Retour aux dispensaires,” Le Figaro, October 7, 1993, 11.

4. See, for example, the five-part series “Tuberculosis: A Killer Returns” in the New York Times, October 11–15, 1992; Robert D. McFadden, “TB Kills 13th Inmate in New York Prison System,” New York Times, November 17, 1991; Dennis Hevesi, “New York City Considering Quarantine of TB Patients,” New York Times, February 22, 1992; and Geoffrey Cowley, “Tuberculosis: A Deadly Return,” Newsweek, March 16, 1992, 52–57.

5. For example, Barbara Day, “Deadly TB strains could swell to AIDS proportions,” The Guardian (New York), February 19, 1992; Cowley, “Tuberculosis: A Deadly Return,” also emphasizes the role of poverty and “social deprivation” in the resurgence of tuberculosis, while also calling for surveillance-oriented public-health “control measures” as a first line of defense against the disease. See also the thoughtful historical review by Barron H. Lerner, “New York City’s Tuberculosis Control Efforts: The Historical Limitations of the ‘War on Consumption,’ ” American Journal of Public Health 83 (1993): 758–766.

6. There is already a vast and rapidly expanding literature on AIDS in cultural and historical perspective. See, among others, Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989); Allan M. Brandt, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880, expanded ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); and Elizabeth Fee and Daniel M. Fox, eds., AIDS: The Burdens of History (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Oxford: University of California Press, 1988).

7. Even in the nineteenth century, anxiety over transmission of bovine tuberculosis to humans was less acute in France than it was, for example, in Great Britain or the United States. It has been estimated that in the days before widespread surveillance and regulation of milk and meat supplies, only 2 percent of all cases of pulmonary tuberculosis and 30 percent of nonpulmonary forms were attributable to bovine infection. This would amount to less than 10 percent of all cases of tuberculosis. Linda Bryder, Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 3, 133.

8. For epidemiological developments since the mid-1980s, see Sudre et al., “Tuberculosis: A Global Overview of the Situation Today”; Asim K. Dutt, guest editor, “Update on Tuberculosis,” Seminars in Respiratory Infections 4, no. 3 (September 1989); Peter F. Barnes et al., “Tuberculosis in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection,” New England Journal of Medicine 324 (1991): 1644–1650; “Tuberculosis Outbreak Among HIV-Infected Persons,” JAMA 266 (1991): 2058–2061; Stephen D. Ciesielski et al., “The Epidemiology of Tuberculosis Among North Carolina Migrant Farm Workers,” JAMA 265 (1991): 1715–1719; Dixie E. Snider, Jr., et al., “Editorial: Tuberculosis and Migrant Farm Workers,” JAMA 265 (1991): 1732.

9. See, for example, William W. Stead and Joseph H. Bates, “Epidemiology and Prevention of Tuberculosis,” in Alfred P. Fishman, ed., Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988), 3:1795; for other relatively accessible medical overviews of tuberculosis, see A. R. Rich, The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis, 2d ed. (Springfield, Ill.: Charles C. Thomas, 1951); Paul T. Chapman, “Tuberculosis,” in Franklin H. Top, Sr., and Paul F. Wehrle, eds., Communicable and Infectious Diseases, 7th ed. (St. Louis: C. V. Mosby, 1972), chap. 67; H. William Harris and John H. McClement, “Pulmonary Tuberculosis,” in Paul D. Hoeprich, ed., Infectious Diseases, 3d ed. (Philadelphia: Harper and Row, 1983), 378–404; and National Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Association, Introduction to Respiratory Diseases, 4th ed. (n.p.: National Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Association, 1969), 31–45.

10. See, for example, Centers for Disease Control, “National Action Plan to Combat Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, June 19, 1992, 5; “D.C. Targets Homeless in TB Battle,” Washington Post, January 11, 1993, A12; “Tuberculosis: A Killer Returns,” New York Times, October 11, 1992, 44; Cowley, “Tuberculosis: A Deadly Return,” 54.

11. Ian Sutherland, “Recent Studies in the Epidemiology of Tuberculosis,” Advances in Tuberculosis Research 19 (1976): 1–63: “In those in whom progressive disease develops, it does so in the great majority within at most 1 or 2 years of infection” (44). S. H. Ferebee, “Controlled Chemoprophylaxis Trials in Tuberculosis: A General Review,” Advances in Tuberculosis Research 17 (1970): 28–106; this latter article surveys the results of thirteen controlled studies (seven in the U.S., six in other countries) concerning the “risk of infection” and the “risk of disease” among stable populations studied over a period of years, as well as the role of preventive treatment with isoniazid in reducing the risk of disease for those infected. In these trials, the results of the placebo groups provide the figures for risk of disease in the general population. For another extremely detailed epidemiological study, see J. Frimodt-Møller, “A Community-Wide Tuberculosis Study in a South Indian Rural Population, 1950–1955,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 22 (1960): 61–170.

12. This is the view of, among others, René Dubos, the physician and historian/philosopher of medicine. See his Mirage of Health: Utopias, Progress, and Biological Change (New York: Harper, 1959), 63–64.

13. Arthur M. Dannenberg, Jr., and Joseph F. Tomashefski, Jr., “Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis,” in Introduction to Respiratory Diseases, 1833–1837.

14. Thomas McKeown, The Modern Rise of Population (London: Edward Arnold, 1976); The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979); and The Origins of Human Disease (London: Basil Blackwell, 1988).

15. Simon Szreter, “The Importance of Social Intervention in Britain’s Mortality Decline, 1850–1914: A Re-interpretation of the Role of Public Health,” Social History of Medicine 1 (1988): 1–37; Allan Mitchell, “An Inexact Science: The Statistics of Tuberculosis in Late Nineteenth-Century France,” Social History of Medicine 3 (1990): 387–403; Leonard G. Wilson, “The Historical Decline of Tuberculosis in Europe and America: Its Causes and Significance,” Journal of the History of Medicine 45 (1990): 366–396, and “The Rise and Fall of Tuberculosis in Minnesota: The Role of Infection,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 66 (1992): 16–52. For a partial response to this backlash, as far as nineteenth-century France is concerned, see David S. Barnes, “The Rise or Fall of Tuberculosis in Belle-Epoque France: A Reply to Allan Mitchell,” Social History of Medicine 5 (1992): 279–290.

16. Mitchell, “An Inexact Science” and The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France after 1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 252–275; see also his “Obsessive Questions and Faint Answers: The French Response to Tuberculosis in the Belle Epoque,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 62 (1988): 215–235.

17. For a fuller statement of this argument, see Barnes, “The Rise or Fall of Tuberculosis in Belle-Epoque France.”

18. Sources for tuberculosis mortality figures: Recherches statistiques sur la ville de Paris et le département de la Seine, 6 vols. (Paris: various publishers, 1821–1860), 1: 37, 6: 666, 671; Jacques Bertillon, “Etudes statistiques de géographie pathologique,” Annales d’hygiène publique, 2d series, 17 (1862): 112, 114, 122; Bertillon, De la fréquence des principales maladies à Paris pendant la période 1865–91 (Paris: Imprimerie administrative, 1894), 130–136; Statistique sanitaire des villes de France (Melun: Imprimerie administrative, yearly), 1887–1913.

19. McKeown, The Role of Medicine, 92–96.

20. Bertillon, De la fréquence des principales maladies, 130–136.

21. Maurice Lévy-Leboyer and François Bourguignon, L’Économie française au XIXe siècle (Paris: Economica, 1985), 19.

22. Recherches statistiques, 1: 37, 6: 666, 671; Bertillon, De la fréquence des principales maladies, 133.

23. Throughout the book, conforming to nineteenth-century usage, I use the somewhat awkward term “hygienist” to refer to public health experts or professionals. Some were medical doctors, and others were not, but they all concerned themselves primarily with the study and improvement of public health.

24. See, for example, Etienne Lanthois, Théorie nouvelle de la phthisie pulmonaire, 3d ed. (Paris: Adrien Egron, 1822), 236–237; P. C. A. Louis, “Note sur la fréquence relative de la phthisie chez les deux sexes,” Annales d’hygiène publique, 1st series, 6 (1831): 49–57.

25. Alain Cottereau, “La Tuberculose, maladie urbaine ou maladie de l’usure au travail?” Sociologie du travail (1978): 192–224.

26. The most recent and melodramatic example of this approach is Frank Ryan, The Forgotten Plague. Others include, to varying degrees, Pierre Guillaume, Du désespoir au salut: Les tuberculeux aux 19e et 20e siècles (Paris: Aubier, 1986); Mark Caldwell, The Last Crusade: The War on Consumption, 1862–1954 (New York: Atheneum, 1988); R. Y. Keers, Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Journey Down the Centuries (London: Baillière Tindall, 1978); George Jasper Wherrett, The Miracle of the Empty Beds: A History of Tuberculosis in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977); J. Arthur Myers, Captain of All These Men of Death: Tuberculosis Historical Highlights (St. Louis: Warren H. Green, 1977); Harley Williams, Requiem for a Great Killer: The Story of Tuberculosis (London: Health Horizon, 1973); and Charles Coury, Grandeur et déclin d’une maladie: La tuberculose au cours des âges (Suresnes: Lepetit, 1972). Three recent exceptions to some of these historiographical tendencies are Linda Bryder, Below the Magic Mountain; Dominique Dessertine and Olivier Faure, Combattre la tuberculose (Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1988); and Michael Teller, The Tuberculosis Movement: A Public Health Campaign in the Progressive Era (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988).

27. Guillaume, Du désespoir au salut; Dessertine and Faure, Combattre la tuberculose; Isabelle Grellet and Caroline Kruse, Histoires de la tuberculose: Les fièvres de l’âme, 1800–1940 (Paris: Ramsay, 1983); Bryder, Below the Magic Mountain; F. B. Smith, The Retreat of Tuberculosis, 1850–1950 (London: Croom Helm, 1988); Barbara Bates, Bargaining for Life: A Social History of Tuberculosis, 1876–1938 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992); Caldwell, The Last Crusade; Teller, The Tuberculosis Movement; Ryan, The Forgotten Plague.

28. Guillaume, Du désespoir au salut, 8.

29. Grellet and Kruse, Histoires de la tuberculose, 15.

30. Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 8.

31. Dominique Dessertine and Olivier Faure, “Malades et sanatoriums dans l’entre-deux-guerres,” and Didier Nourrisson, “Tuberculose et alcoolisme, ou du bon usage d’un aphorisme,” in Jean-Pierre Bardet et al., eds., Peurs et terreurs face à la contagion: Choléra, tuberculose, syphilis, XIXe-XXe siècles (Paris: Fayard, 1988), 218–235 and 199–217, respectively.

32. William Coleman, Death Is a Social Disease: Public Health and Political Economy in Early Industrial France (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982); Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830–1910 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987).

33. David Armstrong, Political Anatomy of the Body: Medical Knowledge in Britain in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 7–11.

34. Brandt, No Magic Bullet, 5.

35. Otto Lorenz, Catalogue général de la librairie française, vols. 8–27 (Paris: various publishers, 1880–1920).

36. Joseph Grancher, “Sur la prophylaxie de la tuberculose,” Bulletin de l’Académie de Médecine, 3d series, 39 (1898): 470, 478–479, 481. (Emphasis added.)

37. Commission de la tuberculose, Moyens pratiques de combattre la propagation de la tuberculose (Paris: Masson, 1900).

38. Commission permanente de préservation contre la tuberculose, Recueil des travaux, 4 vols. (Melun: Imprimerie administrative, 1903–1913).

39. Lionel Amodru, deputy, “Rapport fait au nom de la commission d’hygiène publique sur les mesures à prendre pour arrêter les progrès de la tuberculose,” Journal officiel: Annexes de la Chambre des députés, session of June 21, 1901, 782.

40. Ibid., 785–786.

41. Ibid., 787.

42. Le Petit Havre, October 3, 1905, 1.

43. On this period, see especially Dessertine and Faure, Combattre la tuberculose, and Lion Murard and Patrick Zylberman, “L’autre guerre (1914–1918): La santé publique en France sous l’;oeil de l’Amérique,” Revue historique 276 (1986): 367–398.

44. Susanna Barrows, Distorting Mirrors: Visions of the Crowd in Late Nineteenth-Century France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 2.

45. Robert A. Nye, Crime, Madness, and Politics in Modern France: The Medical Concept of National Decline (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), xii–xiii. (Emphasis in original.)

46. Ibid., 139–140.

47. Louis Chevalier, Laboring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris During the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, trans. Frank Jellinek (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981); Catherine J. Kudlick, “Disease, Public Health and Urban Social Relations: Perceptions of Cholera and the Paris Environment, 1830–1850” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1988); see also chap. 1, below.

48. See, for example, Nye, Crime, Madness, and Politics, 184–185.

49. Some of the best examples of this brand of history have come from Charles Rosenberg and his colleagues and students at the University of Pennsylvania. See, for example, Charles E. Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System (New York: Basic Books, 1987); Rosenberg, Explaining Epidemics and Other Studies in the History of Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); Charles E. Rosenberg and Janet Golden, eds., Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992). Another recent book has applied this patient-centered perspective to the history of tuberculosis in the United States: Bates, Bargaining for Life.

50. A recent collection of essays representing this approach is Andrew Wear, ed., Medicine in Society: Historical Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).