Introduction

Sacred Words, Sanctioned Practice, New Communities

Barbara D. Metcalf

| • | • | • |

Diaspora Muslims and “Space”

The essays in this volume explore aspects of the religious life of the new Muslim communities in North America and Europe, communities largely made up of immigrants and their offspring, and, in the case of African-Americans, converts.[1] In the United States and Canada, the immigrant Muslim populations have been dominated by professionals and have formed a relatively small proportion of the population, probably some three to four million people. The African-American population, probably at most about one million, while including some members who are among the educated and steadily employed, often represent the less privileged, not least the prison population discussed in one essay below. On the whole, political concerns about a Muslim presence have been muted in North America, the one exception being the alarm about Muslims at the time of the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993.

In France and Britain, by contrast, and to some degree in Germany, largely working-class Muslim populations have been a major issue in public life. In France, Islam is regularly described as the “second largest religion,” after Catholicism, its adherents numbering some four to five million. The Muslim populations in Britain and Germany, although fewer than in France, are more visible than in North America, in part because of their more concentrated settlements, and have also been much discussed in public life. These populations also vary in their countries of origin. Muslim immigrants from the Indian subcontinent (including India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) have predominated in the populations in Britain itself and in Canada. Muslim immigrants in France have been largely from North Africa and, to a lesser degree, French West Africa; those in Germany, from Turkey. A recent estimate puts the number of Muslims in Western Europe, the United States, and Australia at more than twenty million (Robinson forthcoming).

Many Muslim migrants came originally as industrial workers, beginning in the 1950s; by the early 1970s, many began to settle with their families. Since then, not only have many Muslims been attempting to sustain and reproduce distinctive cultural values in a non-Muslim setting, they have also, in many cases, been doing so in the company of fellow Muslims whose practices originated in homelands different from theirs. These diaspora Muslims now find themselves in countries that vary demographically, economically, and juridically. Despite this variety, their shared experiences have produced some commonalities in their engagement with the Islamic tradition and their modalities of creating late-twentieth-century communities. They have, moreover, not negotiated such issues in isolation: Muslims today are tied together globally through a range of institutions and media that further suggest the appropriateness of studying this “diaspora” as a single phenomenon. There are, of course, new Muslim communities outside North America and Europe—in Australia, for example. And “old” communities, as will be clear in many of the essays below, are engaged in many of the same processes as the new. Nonetheless, the particularities set up by the new Muslim presence in the “West” seemed to us sufficient to justify its study on its own.

As for singling out the “Muslim” identity of these groups, we do so, of course, without assuming that anyone labeled Muslim focuses wholly on Islamic cultural expressions in place of all other loyalties. For some, other networks, such as class or professional organizations, have proven more important. This has at times, for example, been the case with groups ranging from embattled “blacks” in Britain to wealthy professional or business groups among Iranians in Los Angeles. Some researchers have used surveys to show a marked falling away from religious practice among second-generation Muslims in France.[2] Typically, those we study live in a web of loyalties and networks that may well take on different emphases in different contexts and at different times, and that typically change in the very processes of social and political life. A Muslim identity has, however, been important and has entered into public life at both local and national levels.

To explore the cultural life of these populations, we have chosen to focus on the theme of “space.” Many of these Muslims have themselves moved physically from one geographic area to another, and they, their offspring, and converts as well often have a vivid sense of “displacement,” both physical and cultural. Each essay, to varying degrees, explores issues of space in the multiple senses of that word, seeking to delineate the “social space” of networks and identities created as individuals interact in new contexts, as well as the “cultural space” that emerges in a wide variety of ways as Muslims interact with one another and with the larger community. In some cases that interaction entails “physical space”: the very right of residence, the erection of community buildings, the processions that mark an urban area. The emphasis on space allows us to explore Muslim cultural practices beyond the articulations of elites to the everyday practices of ordinary people. And this focus guides us to values and to (dis)unities that define moral and social life.[3]

Simplest to identify are visual clues to the presence of Muslims: people distinguished by beards or head coverings, for example, and the ever-increasing array of objects distributed by Islamic shops and catalogues: posters, hangings, mugs, bumper stickers, key chains, jewelry, and so forth—a modest “commoditization” of Islam. Similarly, the outsider may look for built or altered environments—homes, mosques, shops, neighborhoods—that seem “Muslim.” But “Islamic architecture” proves to have complex meanings. Certain Middle Eastern architectural styles are often, to be sure, taken by the larger population as quintessentially Muslim—an unfortunate stereotyping, as Gulzar Haider argues below, in which arches and domes were enthusiastically used in the United States as shorthand for self-indulgence, luxury, even decadence, in gambling casinos, movie halls, and the like.

It is all the more ironic, therefore, that Muslims in Europe and America today have turned in many cases to such conventional styles. Thus, in one American college town, the Muslim Students’ Association recently worked with picture books and a local restaurant designer to plan what the architect called “the prettiest traditional mosque on the East Coast” (Raleigh News and Observer, January 3, 1989 )—one that could, quite simply, have been set down anywhere.[4] Yet clearly, if one reviews Islamic architecture throughout history, no such single style emerges, to the point where the art historian Oleg Grabar has proposed that “traditional Islamic culture identified itself through means other than visual,” and certainly not by conventions of architectural form (Grabar 1983: 29).

In light of Grabar’s cautionary comments on architecture, the visual—although easiest to apprehend, and privileged in European thought—should not be taken as primary. Virtually every essay here emphasizes that it is ritual and sanctioned practice that is prior and that creates “Muslim space,” which thus does not require any juridically claimed territory or formally consecrated or architecturally specific space. The essays, moreover, describe people whose personal and community lives may be engaged at multiple sites on different continents, or even people who seem to transcend sites completely, caught up in global movements of proselytization and trade, so that they essentially exclude the outside world to carry with them a world of ritual, relationships, and symbols that creates some variety of Muslim space wherever they are present.

This new space, one might suggest, is largely created by humble “post-modernists” creating their own cartographies and living the new globalization implicitly as they travel and interact with one another (Rouse 1991). But there are also intellectuals, such as the late Ismail al Faruqi, Seyyid Husain Nasr, and many others, who challenge narratives that objectify diaspora Muslims as the proletarians or underclass of late capitalism, disadvantaged Third World migrants in need of modernity, or materialist professionals contributing to the brain drain. Instead, invoking the powerful Islamic concepts of hijra (migration, “hegira”) and da‘wa (mission, invitation), they see themselves as providentially poised to both challenge and render service to the “West” through the defense and spread of Islam. Muslims, inhabiting their own imagined space, thus become subjects in a cosmic history of their own making, far greater than the narrow histories of Marxism or nationalism handed to them.

| • | • | • |

Words in the Islamic Tradition

What constitutes a Muslim space? We might well expect to find characteristic Muslim patterns in a context like this where people have experienced the kind of cultural displacement, whether through migration to a largely non-Muslim area or, in the case of many African-American Muslims, through conversion, that places them in the kind of “borderland” likely to illuminate cultural processes and characteristic practices. Muslims are Muslim precisely in the sense that they are people who, across time and place, engage with what Talal Asad (1986) calls “a discursive tradition” created by interaction with sacred texts and with the history of that interaction.

A central theme that emerges in these essays is the individual and corporate recitation, display, and transmission of sacred words as a focus of Muslim worship and of moral behavior. Over and over, in context after context, we find elaborations of practice—in the very specific sense of ritual centered on sacred words—coupled with attempts to organize everyday life in the light of those words. If there is a recurrent visual clue to a Muslim presence in these multiple settings, it is above all those Arabic words, whether as documents—calligraphy on paper, objects, and buildings—or as talismans. The Arabic script alone has served historically as a constant visually perceived symbol of Islam (Grabar 1983: 29), often supplemented today by the images of the holy shrines at Mecca and Medina.

For a Muslim to feel at home or for a non-Muslim to recognize a Muslim space, the presence of certain spoken and written Arabic words is most telling. Even when they arrive in unknown places, familiar Arabic dicta greet Muslims from Arabia to China, from Detroit to Mali: “Bi’smi’llah” (In the name of Allah), “Al-hamdu’llah” (Praise to Allah), “Insha’llah” (If Allah wills). Now that Islamic symbols have become so much a part of public space, the Arabic name of Allah and other phrases leap out from billboards or vehicle decorations (Starrett 1992: 1–4). The photographs of calligraphy in a Muslim home in Canada and an African-American Muslim home in Philadelphia, below (figs. 10a-b and 14), depict a use of sacred words widespread among Muslims everywhere (Qureshi, McCloud, this volume). Public processions display moving “texts,” not in some abstract sense, but on the placards that are carried (Slyomovics, Schubel, Werbner, this volume).

And beyond the words, one encounters shared practice. The linkage between sacred word and practice is clear. Clifford Geertz has elaborated this point by noting that Islamic buildings are primarily spaces where the faithful engage with sacred words, whether in prayer (the mosque), education (the madrasa), or meditation (the khanaqah).[5] Grabar, even while seeking to analyze a specific design feature of a class of mosques (the placement of tiled panels in mosques of Safavid Iran), again resorts, albeit tentatively, to the priority of practice:

In chapter 1, Gulzar Haider describes his own most recent designs as ones that circle back to this kind of inspiration.In the Masjid-i Shah’s main dome seems to me to be an extraordinary attempt at symbolizing the Revelation not as the static and learned order of a Gothic portal or of a Byzantine church but as the dynamic and sensuous illumination of a faithful praying. The symbolism of the decoration is not inherent to the design but is the result of man’s prescribed action in the building. (Grabar 1983: 30)

That these enduring themes are evident, indeed thrown into high relief, in the context of today’s diaspora Muslims validates the emphasis on the importance of studying “border” populations, those living in contact with other peoples, for understanding enduring characteristic processes and themes. At the same time, and equally gratifying, it links what are often the most humble of communities, deprived of material resources and marginalized in relation to the surrounding cultures, to the great historic periods, studied by scholars like Grabar and constituting the pride of all Muslims, of the classical past.

These themes of the preeminence of sacred words and normatively enjoined practices as the core of cultural elaboration, transformation, and reproduction are evident in the entire collection of essays presented here, both those in the first section, which emphasize interaction among Muslims, and those in the second, which turn to interactions with the larger society.

| • | • | • |

Making a Space For Everyday Ritual and Practice

Part 1 of this book looks particularly at Word-centered ritual and Word-sanctioned practice in the context of Muslims interacting with one another and not oriented to the larger community. The difficulty of maintaining this distinction is signaled by chapter 7, the first essay in Part 2, on imprisoned African-American Muslims, who, one might argue, are merely engaged in the same kind of inner-focused activities as Muslims in their Canadian or Philadelphia homes, in French foyers, and in community mosques, the subjects of other essays in Part 1. Imprisoned Muslims, however, engage in continuous negotiation with prison officials to allow the ritual practices—which, after all, define such basic daily matters as schedule, food, and dress—they seek to follow among themselves.

A significant dimension of this practice in these new contexts is the utter “portability” of Islamic ritual. As Akbar Muhammad, himself rooted in the American Muslim experience, has emphasized, Muslim ritual requires no “sacred place.” There is no formula of consecration or deconsecration of a site of worship, and historically mosque sites have been used, not only for praying, but for everything from doing business to levying troops (oral comments, May 13, 1990). That it is the activity that defines a place is nicely illustrated by an anecdote told by Heidi Larson based on conversations with Muslim children in Southall, London, who spoke often of going to the mosque for Qur’an study. The “mosque” proved to be an Anglican church, which made space available to Muslims for children’s education. Similarly, among Americans, the term mosque can be used of a group of people uniting for worship, rather than of a building. Surveys of American Muslims have, moreover, shown little correlation between conceptions of “being a good Muslim” and mosque attendance (Haddad and Lummis 1987: 27, 35).[6] This interpretation of the relative insignficance of the physical mosque resonates with normative Muslim resistance to sacralizing any object and thus risking shirk (polytheism). That mosque buildings may become deeply significant in certain historical contexts, including those discussed in Part 2 here, is of course equally the case. But for ritual, it is the practice, not the mosque, that matters.

The essays show how these enduring themes are recreated and reimagined in new settings. An outsider might think that ritual and sanctioned practices among migrants are merely a clinging to the past, continuing the cultural practices of the communities they have left behind. This impression is heightened by the presence of “imported” religious leaders and of ghettoes or neighborhoods—rue Jean-Pierre Timbaud in Paris, Brick Lane in London, Manningham in Bradford, Kreuzburg in Berlin—that seem to reproduce the home country. One manifestation of the assumption of continuity has been the European television programs meant to provide education about immigrant rituals and celebrations by filming those rituals in the home country.[7] German television, for example, prepared programs on ‘Id al-Fitr and the Prophet’s birthday filmed in North Africa (Arabia, November 1984).[8] Such an approach, as has been effectively argued in relation to similar filming of the Caribbean Carnival as a presumed way of understanding such rituals in Britain, assumes a fossilization of practice and fails, above all, to see the new meanings such practices take on in a new environment. Carnival in London’s Notting Hill, for example, is clearly linked to the sociological position of the immigrant black population (Diawara 1990). We cannot assume that the old and new cultures are fixed, and that change results from pieces being added and subtracted. Instead, new cultural and institutional expressions are being created using the symbols and institutions of the received tradition.

What then is new? One significant change is the very fact of such representations as television programs, and, even more, of Muslims’ own initiatives that define, “objectify,” and represent “Islam.” This “objectification” (Eickelman 1989) has been advanced, not only in America and Europe but in lands of origin as well, by modern education, the media, and by Islamic movements. “Objectification” entails self-examination, judging others, and judging oneself. The sense of contrast—contrast with a past or contrast with the rest of society—is at the heart of a self-consciousness that shapes religious style. “I’m always aware that I’m a Muslim, that when I go out I represent Muslims and [must not] do anything [that would cause people to] blame Muslims,” a young woman in Bradford said.[9] The Muslim migrants are themselves largely products of postcolonial countries where interaction with Europeans and European cultures has been lengthy. They are in no sense untouched “traditional” people encountering “the West.” In moving to Europe, migrants from rural areas in many cases replicate processes common in their own countries when people move from countryside to city and settle among diverse populations coping with industrialization, electoral politics, modern architecture, and the assaults of transnational consumer culture on every side (Mandel, this volume). Many are people who have moved before (Shaw 1988). These processes are intensified in North America and Europe and given additional salience by the very fact of living in what is imagined as “the West,” materialist, exploitative, licentious, and, at once, godless and Christian.

Werner Schiffauer, who has studied Turkish peasants in their home villages in Anatolia as well as in urban Turkey and Germany has coined the expression “the islamization of the self” to describe a central dimension of this “objectification.” He describes a pattern of religious practice bound up with the rhythms of everyday life and shared by the whole society in Anatolia; in contrast, among migrants, he finds withdrawal from the larger society to enter the religious community, which becomes, as he puts it, a counterweight, a place of respect (Schiffauer 1988: 134).

Similarly, Akbar Muhammad, using oral histories of African-American Muslims describing life up to the 1930s, has shown how mosques themselves were seen as a site of hijra and known as mahjar and given names like Masjid al Medina (to recall the Prophet’s great hijra), in a way that did not have classical precedents. We are reminded of how the founding event of the Muslim community, the hijra, a charged spatial metaphor in itself, comes to stand for a properly conducted Muslim life. The mosques, like the Muslim home, were meant to stand apart from the mundane and alienating world (oral comments, May 13, 1991). So even practices exclusive to Muslims, even hidden from outside view, are changed by the very fact of their larger context.

For some Muslims, there is a particular sense of merit and satisfaction because of the difficulties of practice in a larger environment that is not Muslim. A Turk in Paris, for example, explained, “It is more important to live Islam in France than in Turkey: to know how to follow practices and customs in a society not yours is a greater achievement” (Kastoriano 1987: 841). Several New York Muslims interviewed during Ramadan made the same point. A Pakistani-American surgeon, for example, questioned the practice in Muslim countries of “artificially changing their schedules” during Ramadan (which requires daylight abstinence). “Absolutely, you get more benefit here than when you just make your a.m.’s your p.m.’s.” And a Lebanese-American businessman agreed: “People get a joyous feeling because they have accomplished something in a place where they didn’t have to” (New York Times, March 6, 1992).

A particular absence in a largely non-Muslim environment is the lack of Islamic sounds, the sound of the azan (call to prayer) and the sound of Qur’anic recitation, the latter especially marked in the nights of Ramadan. A Long Island Arabic teacher noted that he had a timer to turn on a recording of the azan in his home (New York Times, March 6, 1992).[10] Catalogues from Islamic shops and newspaper advertisements aimed at Muslims are full of such items to create the sounds of an Islamic space. An electronic “Azan Clock,” for example, its digital display set in a replica of a domed mosque, can be set for the five daily prayers. Qur’anic tapes, produced in different styles and in different selections are widely available and certainly portable: as a poster at the Islamic Society of North America urged: “Use Driving Time to Listen to Holy Qur’an” (New York Times, September 3, 1990). Other devices (“qibla compasses”) available in French and American shops allow one to orient oneself to Mecca throughout the world, a critical skill for prayer, as well as for sleep, toilets, and burial—see, for example, advertisements in the Arrayah Newspaper (Philadelphia) and Al Nur: The Islamic Center Quarterly (Washington, D.C.).

Special perfumes or essences worn by men to congregational prayer are also often available. I accompanied a young Zanzibar-born Canadian Muslim to a Cairo market to find perfumes to take home to American Muslims reluctant to use local products that might have an alcohol base. Again, there is the sense of satisfaction in overcoming obstacles to find ways to create the sounds, smells, and practices that define Islamic space. This very sense of achievement is a further distinction of contemporary practice in non-Muslim areas.

A second marked characteristic of Muslim practice in the diaspora, closely associated with “objectification” and “islamization of the self,” is simply greater concern with Islamic practice. At the most basic level, increased wealth, even for those relatively poor in their new setting, allows ceremonial and ritual activities not possible for the poor in their place of origin. Indeed, normative practice and sponsorship of ritual events has often been associated with the well-born, so that, as Katy Gardner (1995) has shown for Sylhetis in Britain, migrant prosperity and observant religious style are linked in seeing migration as a source of blessing—and of enhanced social status.

A series of oral histories recorded in Bradford in the mid 1980s are suggestive of a transition to a higher level of religious practice in many individual lives. Thus a migrant from Mirpur, born in 1932, who arrived in Dewsbury to do factory work in 1961, described such change:

Migrants may thus distinguish themselves from their individual and collective pasts. A young Bradford-born woman, who spent her teenage years in Pakistan, recalled her own childhood education: “The teaching in Pakistan doesn’t teach you to understand the words” (BHRU: CO83 29.10.86). Another criticized Pakistanis for having to appear religious (Mirza 1989: 26). For converts, of course, the very fact of a life of discipline and sanctioned behavior, typically seen as a dramatic break with one’s past, often represents part of the great attraction of Islam.Oh, we’ve been very fortunate…we’re very grateful to Allah for keeping our children on the path of Islam. They haven’t gone away from their culture or their religion, unlike myself, when I came over to England there was no mosque in England; there was no way of telling when…we have to fast .…We were quite isolated…so we just used to celebrate Eid whenever we could. (BHRU: CO123 8.9.87 Punjabi)

Has practice also changed by the embrace of normative patterns—not only more practice but “correct” practice—at the cost of former local customary behavior? This has been the goal, indeed the expectation, of some Muslim leaders, who have hoped that in a new setting, particularly when Muslims from different areas were joined together, individuals would examine their practices in the light of scriptural norms and focus on what was sanctioned and could be common to all.[11] Several of the essays below emphasize that kind of religious style, a style, of course, common among certain groups in Muslim places of origin as well. In the United States, the Islamic Society of North America, which is strongly linked to professionals and university populations, has particularly urged Muslims to overcome ethnic customs in favor of a shared normative practice. “The U.S. is the cutting edge,” a Muslim graduate student at Harvard told me. “[Here] Muslims strip away centuries of innovation and succeed in getting to the essence.”

The case of sectarian groups in the diaspora is particularly striking. In recent years, several such groups, long regarded as outside the mainstream have, in some respects, modified their interpretations and practices to conform more to those of the majority. The Isma‘ilis, who have substantial communities in the diaspora, now conflate their relationship to the Aga Khan with patterns characteristic of a Sufi tariqa (rite, brotherhood), and cultivate cultural expressions shared by Muslims generally, among them architecture (in the project described in Holod 1983), and philanthropic work, including economic development. The Aga Khan himself has argued that the colonial period was one that encouraged groups to emphasize difference, whereas the contemporary situation allows for seeking commonalities. The Senegalese Mourides, Moustapha Diop has noted, have of late turned to emphasize shared Muslim symbols, encouraging the pilgrimage to Mecca rather than only that to Touba, site of their founder’s tomb (cf. Ebin, this volume).

The Ahmadiyya, legally declared non-Muslim in Pakistan in 1974 and subsequently banned from Mecca, make a claim to a shared Muslim identity by the very architecture of the mosque designed by Gulzar Haidar, which he discusses below. Since 1984, the Ahmadiyya movement has made its headquarters in Britain (Lewis 1994: 98). The Ahmadi, like the Alevis in Berlin discussed by Ruth Mandel, illustrate greater opportunities for free expression than many old Muslim areas allow. The Alevis have flourished as they could not in Turkey, not only because of this freedom but because the very practices read as “libertine”—for example, in relation to women’s behavior and dress—have been judged approvingly as “liberal” in Europe. Indeed, the British Muslim writer Shabir Akhtar has argued that “the freest Muslims live in the West and in Iran. Everywhere else, Islam is an outlawed political force” (Lewis 1994: 52).

The move to what is perceived as Islamically sanctioned, normative practice has, moreover, been encouraged by a range of other transnational movements not studied directly but alluded to in various essays, including the Saudi Rabita al-‘Alam al-Islami (World Muslim League). A wide variety of media link Muslims as well. They may be geared to a particular country even while communicating common themes: thus a call-in fatwa show in France can advise on a problem at once French and Islamic: Are snails halal? (Barbulesco 1987). The hajj is televised live in many Muslim countries and available later on video.

A final theme in the changed characteristics or emphases in religious practice in the diaspora has been a push to a more dispersed leadership, more popularly generated, for religious observances and community representation. Women appear to play a central role, whether formally in mosque organization (Haddad and Lummis 1987: 131) or informally in the context of devotional assemblies described below (Qureshi, this volume). In the United States and elsewhere, Muslims elect prayer leaders or imams instead of receiving officials appointed by the state. Muslim prisoners in the United States have in some cases, as described by Dannin below, struggled to sustain the practice of identifying their own leadership instead of accepting state-appointed “chaplains,” arguing that such practice reflects scriptural norms. Some mosque congregations in the United States have no salaried imam at all, but rotate leadership among the members themselves (Haddad and Lummis 1987: 61–62). Not only in the diaspora, but everywhere, movements like the Tablighi Jama‘at have made an emphasis on diffused, group-chosen leadership central to their operation, in contrast to the exclusive leadership of the old elites. Thus changes in leadership roles, in some cases intensified by residence in the diaspora, are part of changes taking place worldwide.

In looking at interaction among Muslims, the two final essays in Part 1, on the Mourides and on Tablighi Jama‘at, emphasize the way in which shared behavior and devotional practice—shaped and given meaning in all its different environments—create a world for adherents replicable everywhere. For Tablighis, the sentiment expressed by a Brooklyn shopkeeper observing Ramadan—“the same food, the same moon…God is everywhere”—reaches its extreme. It is themselves, and their fellow Muslims as embodiments of Muslim ritual and practice, that define any place as Muslim space. Tablighis sit lightly on the earth. When a group of us touring London mosques came to the Tabligh center (a former synagogue), a courteous young man explained that at this mosque “there was nothing to see”; for that, we should go to the (Saudi-supported) London Mosque in Regent’s Park. Reverting to the juridical categories of classical Islam, a young Toronto Muslim explained that where he was, was daru’l-islam. Equally, the Mourides, with their icons, relationships, and cherished qasidas, “carry Touba in their hearts,” so that Marseilles or Manhattan are ultimately indistinguishable. The Shi’a can reproduce Karbala, as described in Part 2 by Schubel, through devotion and ethical action anywhere. In the very act of naming and orienting space through religious practice, we see a kind of empowering of Muslims and a clear form of resistance to the dominant categories of the larger culture.

| • | • | • |

Claiming a Space in the Larger Community: Mosques, Processions, Contestations

Even in the intimate spaces of domestic and ritual life, behavior and meaning are shaped by the context of the larger society. When, in turn, we focus on public expressions of Muslim life, such as the creation of mosques and organization of processions, we again encounter the enduring focus on worship and sanctioned practice coupled with “newness” both in meaning and in modes of institutional organization. What happens depends a great deal on the size and composition of the Muslim community. It also depends on the legal status of immigrant Muslims: whether they are treated as permanent settlers, as has been the case for most in Britain and North America, or are present in some different role, most extreme in the case of German “guest workers,” where it has long been assumed that no permanent immigration takes place (Kastoriano 1987: 149–51).

Everywhere, moreover, religious life is shaped by the nature of the majority society, above all, by its assumptions about the relationship of state and religion. In each national context, Muslims may try or be encouraged to produce institutional and symbolic equivalences to non-Muslim forms; they may also strain at being thus constrained. Further, as Muslims make claims on public space, they encounter resistance to Islam, often defined by racism, that in turn shapes their behavior. Muslim institutional life in the diaspora, like Muslim ritual and practice, cannot be understood as mere continuity with an “Old World” past.

Converts, even if proportionately few, may play an important role in shaping Muslim institutional expressions. Kemal Ali, for example, described the anomaly of a New England mosque including Pakistanis, Middle Easterners, and African-Americans, implicitly ranked in that order in terms of social status and prestige. Yet it has been African-Americans like Ali, with his local knowledge of American society, who push for the kinds of mosque-based activities—basketball teams, for example—that conform to American expectations of the activities of religious congregations (oral comments, September 18, 1988). Khalid Duran (1990) has described the unusually active role taken by women converts in Germany in serving as political intermediaries to state institutions. In Britain, the rock star Yusuf Islam (Cat Stevens) has been at the forefront in seeking state support of denominational schools in order to benefit Muslims (Kureishi 1986: 156–59).

A widespread transformation in most communities has been the creation of “Islamic Centers” offering a variety of educational programs, bookshops, and sites for community gatherings, as well as places for prayer. They may be democratically organized. Or, equally novel, they may have a quasi-diplomatic status. The national flags flanking the Washington Islamic Center, for example, are a reminder of its foundation by diplomatic missions; the Islamic Center in London is served by an imam accredited to the Embassy of Saudi Arabia (Ruthven 1990: 54–55). The role of mosques in many cases has also been changed as they take on new functions. Imams may well serve in capacities beyond that of prayer leader, taking on pastoral, administrative, and ecumenical representational functions they would not do in areas of old Muslim settlement (Haddad and Lummis 1987: 59). In so doing, they replicate local non-Muslim religious organizations.

Beyond these local organizations, the British are particularly notable for their expectation that every religious community will evolve a single hierarchy and leadership: if there is an archbishop of Canterbury, there has, for example, to be a chief rabbi. One university center for the study of Christian-Muslim relations pairs the director-general of the London Islamic Centre with the archbishop as “patrons.”[12] A Muslim activist and educator has called on the government to elevate a Muslim leader (presumably parallel to the Anglican bishops) to the House of Lords (Badawi 1981: 30). Nothing more astonishes continental European visitors to Britain than the official encouragement given to Muslim organizations.[13] Thus the Council of Mosques in Bradford was established in 1980 partly on the initiative of the city council, which wanted a single body representing mosques and other Muslim organizations to deal with (Ruthven 1990: 81). The Council of Mosques honed its political skills on issues related to the “Honeyford affair” (leading to the resignation of an allegedly racist headmaster), and it took a leading role in the book-burning and other actions of protest against The Satanic Verses.[14] A range of other issues, especially involving schools (costume, halal meat, objectionable classes, co-education), have proven to be the sites at which “leaders” and “spokesmen” emerge. In this context, the efforts of Dr. Kalim Siddiqi (d. 1995), with Iranian support, to create a Muslim parliament within Britain took the current institutional logic to an extreme—whatever the disapproval of many Muslims and non-Muslims alike (The Independent, May 5, July 1, 1992).

The British expectation that religious institutions will play a role in public life and that religious education will be part of schooling stands in marked contrast to French secularism. Gilles Kepel has argued the merits of the French system, insisting that the state relate only to individuals and not to communities, and that all evidence of religious affiliation or teaching be kept from schools. The objection (both in France and Belgium) to Muslim girls’ wearing scarves to school typifies this concern (Bloul, this volume). Despite their different positions on government secularism, Kepel lumps together the United States and Britain as Anglo-Saxon, arguing that both have given rise to politicized ethnic communities, breeding black ghettoes on the one hand and crises like the Rushdie affair on the other (Le Monde, November 30, 1989).

Almost inevitably, it is assumed that the content of Islam as a religion parallels that of non-Muslim religions, especially Christianity. While particularly encouraged as part of British “multiculturalism,” the pattern is common. Heidi Larson (1990) in her conversations with schoolchildren in London was continuously educated in Islam in terms of equivalences: for example, ‘Id becomes “our Christmas.” Children are encouraged to visit religious centers of other faiths and to become familiar with other religions. Notwithstanding the concern of some parents, Muslim children in Britain learn to recount Sikh legends, act out the Hindu Ramayana epic, and play roles in the Nativity story (Durham 1992). Likewise, in elite schools in India, the same little boy who is a Shiva devotee in a production of the Ramayana may turn up as a shepherd in a Christmas nativity play.[15]

Some Muslims at least have protested what is implicit in all this: namely, that all religions are, fundamentally, the same and ultimately of equal value. This implication of “multiculturalism” has been explicitly denounced in Britain. Ali Kettani, who has served as a Saudi representative to guide diaspora communities, argues that Muslims in the diaspora must not accept “the belief that all religions are equally valid in the sight of the Creator…[this is] the first sign of religious assimilation” (Kettani 1980: 103).

Muslims have both entered into and strained against the institutional templates of their new societies. In Britain, of course, the Rushdie affair made evident different expectations of what was and what was not the role of government in relation to individuals’ rights and in relation to the demands of specific groups. At root the crisis had as much to do with the colonial past as anything intrinsic to Islam. In British India, put simply, the government had little use for law at the cost of public order. Following communal disturbances in 1924 over the publication of a book called Rangila Rasul (The Merry Prophet), an article was added to the Penal Code allowing books likely to stir up religious sentiment to be banned. That law, like many others, was continued in the successor states and indeed used by Rajiv Gandhi to ban The Satanic Verses itself. Little wonder that British Muslims expected the government in Britain to act as it had in the colonies—but it never had and did not now (Ruthven 1990: 87, 102).

Taken up for political reasons locally and around the world, the actions of the British Muslims, which must be seen as a response on the part of those already assaulted by racism and insults to their culture, were to be the basis and pretext from right and left for even more insults. Muslim assumptions about the superiority of Islam, and the respect and boundaries appropriate to its discussion, continue to sit uneasily in a context of secularism and cultural relativity.

In France, the strains against the allocated slot for religion have come with the desire to have religious practice in what is regarded as public space. The pressure for mosques within the foyers and factories was regarded as regressive by labor movements whose triumph had been to keep Church authority at bay. The issue of scarves for Muslim schoolgirls similarly seemed to undermine the hard-won French principles of secular liberty in public space. The French have heard challenges such as, “You think you are in France, but the earth belongs only to Allah! It is our mission to ‘Koranize’ the region,” however rare, with great concern (The Times [London], November 27, 1989).

As in the British case, the most cherished values of the culture seemed to be threatened: freedom of speech, secularism, the rights of women to equality (if the scarf was interpreted, as it was, as a symbol of restriction of women). Thus, on the scarf: “Ce fantastique retour en arrière: la légitimation, au nom de ‘la tolérance’ de l’inégalité entre les garçons et les filles” (Gaspard 1989).

In the end, both opponents of the veil, citing regression and women’s rights, and the defenders, citing tolerance and pluralism, can be seen to converge in positing a fundamental Muslim difference. Beyond freedom of expression and women’s rights, Muslims have been charged with flaunting yet more principles, those of architectural and landscape conservation, as described below by John Eade, and of animal rights, as noted in relation to animal sacrifice by Moustapha Diop. That at least some of these anxieties masked a “displaced discourse” of fear of difference and racism is indisputable. That very difference, constituted in part in the colonial relationship, had now come home. It had come home, moreover, at a time when the whole project of the nation-state as master of its own autonomous fate—whether economic or military—was clearly at stake. And in the case of Europeans, with the accomplishment of the European Community, political autonomy and cultural identity seemed threatened as well.

Observers have watched with astonishment as Jean-Marie Le Pen’s National Front in France has moved up to gain some 15 percent of the vote. Taking scant pleasure in the fact that “John Bull racists have made less headway over the past decade than their likes elsewhere in Europe,” the Economist (December 7, 1991) expressed fear that hard economic times would be coupled with new kinds of nationalistic politics concomitant with the European union. Stanley Hoffman (1992) attributes recent protest votes in Germany, France, and Italy in large part to the issue of immigration (noting, however, that in France that protest vote was equally divided between Le Pen and the ecologists). Issues of “clandestine immigration” (Miller 1991) and the scientifically specious “threshold of tolerance” target all nonwhites as a problem (Silverman 1991). Attacks on Turks in Germany in the early 1990s were linked to expressions of defensive German nationalism.

Ironically, it has been precisely in such divisive issues as the Rushdie affair in Britain and the affair of the scarves in France that Muslims have shown themselves most clearly as participants in their states of residence. In Britain, as Werbner has perceptively observed, spokesmen for the banning deployed arguments of democracy, equal rights (for example, in application of the blasphemy law), and multiculturalism (Werbner, forthcoming). Similarly, as Bloul shows below, Maghrebi defenders of the right to wear scarves in public, just like opponents, invoked what they saw as normative French values. In part, then, the conflicts represented arguments of emphasis and interpretation in a shared democratic or republican discursive tradition, a point largely missed both by those fearful of the Muslim presence and by those who invoked cultural relativity and tolerance in the name of liberalism.

Yet crises have, in fact, also seen Muslims assert the difference between “Islam” and “the West,” linking the plight of diaspora Muslims to that of Muslims in Palestine, Bosnia, Kashmir, and so forth. African-Americans stress their links to Muslim societies elsewhere, evident in home decoration (McCloud, this volume), the names of mosques such as Sankore recalling the great centers of learning of Timbuktu (Dannin, this volume), and educational and Sufi exchanges with Muslims in places like Senegal (Kemal Ali, oral comments). This stance of Muslim minorities has provoked fears of foreign funding and political conspiracy, but must be seen as only one strand in Muslim political orientations and imagination. Muslims who have taken on a politicized public identity may question the totalizing culture of the nation-state and assert that they are, in fact, distinct (Asad 1990). In this, they participate in the new solidarities that contribute to the changed context of the state today and to the creation of transnational networks of every kind. The “claims” on space are thus complex and not exhausted by ties to the homeland or participation, on whatever terms, in the new state, however important both may be.

The essays on communal religious expressions in mosques and processions must be seen against this context. Gulzar Haider’s architectural career (chapter 1) moved from the creation of mosques meant to obscure a Muslim presence to mosques meant to proclaim it. This change mirrors major shifts in architectural styles quite apart from Islam and is as true in old Muslim areas as new. Meanwhile, as Susan Slyomovics documents in the case of a movie theater (chapter 11), some of the old “Orientalist” buildings can now be “reclaimed.” Mosques now announce a Muslim presence.

The new mosque in Bradford is, for example, to be built on a hill and is meant to be observed; it is a symbol of vigor, surrounded by run-down houses and an abandoned church. Figure 3 shows the groundbreaking being immortalized by a photographer from the mosque, who is himself being photographed by a reporter (presumably) from the local Telegraph and Argus, while a British ethnographer photographs them both in the act of taking photographs. What Muslims in Europe and North America do is watched. “We expect [the mosque] to stand here long after we are gone. People are observing us and in a sense we are representing Islam in France,” the Algerian imam of a Turkish–North African mosque in Lorraine explained to a reporter (New York Times, November 20, 1990).

Figure 3. Laying a mosque foundation, under the gaze of receding photographers, Fairfield Road, Bradford, England, 1986. Bradford Libraries and Information Services, Bradford Historical Research Unit, Oral Histories Project.

The emphasis on architectural expressions in recent decades has been criticized as an undue accommodation to non-Muslim ideas of “sacred space” (Eade, this volume). Thus Hajji Taslim Ali, a participant in the Tablighi Jama‘t (Metcalf, this volume), insists that the only importance of a mosque is its function: “You can pray anywhere so long as it is neat and clean. In the Western world we need a mosque because in the winter you can’t pray outside. This country is cold and draughty” (The Independent, October 17, 1990). The noted architect Abdel Wahed el-Wakil argues, however, that “sacred architecture” is in fact inherent in Islam (ibid.). For many Muslims in the diaspora the importance of the mosque has, moreover, come to rest in its symbolic role as a mark of their presence (Poston 1992: 94–95). Sacred or not, mosques increasingly represent Islam in the West to Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Muslim processions, like mosques, address a non-Muslim audience. The meaning of Muhurram is different if the participants are concerned to demonstrate that “Islam is Peace” to non-Muslims and to show civic goodwill by transmuting self-flagellation into a blood drive (Schubel, this volume). Muslim processions, as Susan Slyomovics notes of the nonritual procession of Muslim World Day in New York, are also walking texts, emphasizing the sacred Word. Although the signboards may be directed at other Muslims, as Werbner notes, they may also address outsiders.

Self-presentation and contestation with the larger community, within the context of the nation-state, contribute to the formation of an ethnic identity defined as Muslim. At the same time, differences among Muslims may, in some contexts, also be salient. In the essays presented here, Islamic practice and behavior take place largely in milieux defined by language, ethnicity, and sect. Indo-Pakistanis meet in one another’s homes to sing, recite, and pray;[16] African-Americans form neighborhoods and worship together in prisons; North African and West African workers in France tend to interact separately; mosques are often ethnically defined. A metaphor for such difference is the design of the mosque in Lorraine mentioned above, which explicitly joins North African and Turkish motifs (New York Times, November 29, 1990). This at once underlines the fact that there are two distinctive communities involved, but that, in this context, they unite as “Muslim.”

| • | • | • |

Imagining Muslim Space

The imagined maps of diaspora Muslims, and the definition of centers and peripheries, like the identities they help focus, may also be multiple and may well vary in different times and contexts. Mecca, usually coupled with Medina, is, of course, for all Muslims a transcendent center (not to be confused with contemporary Saudi Arabia, which is to some Muslims anathema and not a center at all). But the West may also be seen as a center, as many of the essays included here suggest, by reason of the positive value placed on new homes in largely non-Muslim settings—value that is not merely worldly but is linked to deep religious aspirations.

Werbner, for example, shows Muslims deeply involved in life in two countries, Britain and Pakistan. The Manchester Sufis are tied to their current place of abode and employment as well as to the Pakistan mountain setting of their Sufi shrine, a site that is neither their birthplace nor a locus of family ties. Both, Werbner argues, are part of their larger “global sacred geography.” While the Kohat shrine holds special charisma for them, Manchester has also become a site of spiritual power. Both places have been subsumed under the powerful metaphor of “tamed wilderness” through the efforts of a holy saint and performative ritual acts, especially zikr. Katy Gardner’s recent work similarly shows how, to Sylheti peasants at home, Britain, a site of material gain linked with a shift to more rigorous Islamic practice, has now become “the sacred center” at the expense of once charismatic Sufi shrines (Gardner 1995). Comparisons in Europe’s favor also come from newly observant Tunisians, who speak with disapproval of a secular state committed to such “modern” symbols as the Tunisian president eating on television during Ramadan in the interests of industrial productivity. Similarly, they come from Turks who have chosen to abandon Kemalist secularity.

Muslim intellectuals in the diaspora have articulated a heroic role for themselves and their communities. The late Fazlur Rahman, suspect for his modernism in Pakistan and long a professor in the United States, for example, explicitly expected Islamic renewal to come from Muslims in the West, and he himself set such a pattern in his own work. Khalid Duran (1990) has recently made the same point, mentioning by name such Islamists as Bassim Tibi, Smail Balic, and Muhammad Arkoun, a list to which one could add Seyyid Husain Nasr and others based in America and Europe. Zaki Badawi has expressed the same confidence in Islamic intellectual life in the West, convinced that the most profound formulations will come, not from the United States, where life is too easy for Muslims (cf. Haddad and Lummis: ch. 3); not in Britain, where he himself is based; but in France, where Muslims will be challenged by the hardness of life, the deep-held convictions of republican secularism, and the depth of racism (oral communication, 1991). Badawi himself, with the patronage of the Libyan Call Society, has established a college in London to train a new class of Islamic leadership, freed of national traditions, educated in European cultures, and trained in the technologies of new media (Badawi, n.d.).

In describing the choice to reside in non-Muslim territories, certain terms resonate, notably hijra and the always linked term of jihad(see Masud 1990). Various ideas about these terms coexist. Hijra may long have been understood as movement from a land where one could not lead an Islamic life, typically one of non-Muslim rule, to a land ruled by Muslims. Today, it can continue to mean physical movement, this time from a land of Muslim settlement, but of poverty, to a non-Muslim land of greater opportunity. It is this kind of migration that the late Isma’il al-Faruqi addressed, arguing that a hijra can only be justified if understood as a providential opportunity for Muslims to lead other people to Islam and ultimately to reform Islam among Muslims as well (al Faruqi 1985).

Hijra today is also construed as psychic and moral withdrawal, whether from support for governments only nominally Muslim (as in the well-known case of the Egyptian Islamist party, Takfir wa’l Hijra) or in one’s personal life from practices deemed not Islamic. Jihad similarly takes on a range of meanings, derived from its root, “effort,” in corporate and individual commitments of various kinds.

A theme articulated by an engaged observer of Muslims in Australia runs through the essays presented here: “While many, perhaps most, migrants, would see economic betterment, or other non-religious factors, for their decision to migrate, many eventually begin to see the maintenance and strengthening of their Muslim identity and commitment, some even see da‘wa, as [their] important or primary roles” (Ahmad Shboul, personal communication, 1989). This has been the argument of influential thinkers associated with Islamist movements such as the Jama‘at-i Islami, notably in the writings of Khurram Murad, who was educated in the United States and has long been resident in Britain; his writings include Islamic Movement in the West (1981) and Da‘wah among Non-Muslims in the West (1986). Others, like Muzzamil Siddiqui, who has been an active religious leader in California, have insisted that any residence in “Dar ul Kufr,” the “Place of Infidelity,” should be temporary and for some limited objective like training or travel; but this seems to be a minor voice (Poston 1992: 81–90; 32). The challenge of creating communities in new settings, the creation of new Islamic institutions and networks, and the embrace and elaboration of practice and ritual have all been evident, not for all, but for many, of those Muslims who find themselves in the new political, economic, and cultural settings of the West.

In all this, we see Muslims negotiating relationships with other Muslims and non-Muslims in ways that forge communities of larger or smaller scale among those who share loyalty to sacred texts and symbols. This community means that even in situations of hardship like prisons and prisonlike foyers, Muslims are able to speak—in spatial metaphors—of “places of safety” (Diop, this volume) and “islands of knowledge” (Dannin, this volume) apart from the society as a whole that surrounds them.

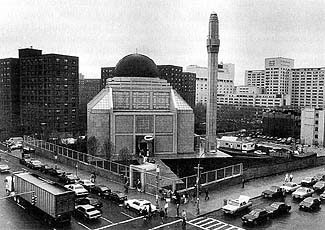

To return to mosque architecture, in some of the best examples we can find an emblem of diaspora Islam as distinct both from the homeland and the surrounding culture. The builders of Manhattan’s new mosque, reflecting in architecture what some have sought for Islam as a whole, have eschewed what might be seen as design characteristics of particular national architectural styles (fig. 4). Shaped by the specific functions needed of a mosque, and drawing on the classic Islamic aesthetic fascination with geometry, the mosque design overlaps with many characteristics of contemporary taste. But in its grassy setting, skewed some 29;dg from the Manhattan street grid to have the proper orientation, the mosque asserts its Islamic distinction. In the judgment of one architectural critic, “the mosque is an island, self-possessed, hewing to a rhythm different from Manhattan’s…its gently sloping, grassy site stand[ing] apart” (Dunlap 1992).

Figure 4. The Mosque of New York at Third Avenue and Ninety-sixth Street, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Photograph Chester Higgins, Jr. / New York Times, April 15, 1991.

From Muslims in the West, we learn much about how Islam, like any historic tradition, exists in the process of redefinition and reappropriation in new contexts. In the situations of cultural displacement or marginality in which these populations find themselves, characteristic Islamic themes and processes of cultural negotiation are thrown into particularly high relief. In seeing this, moreover, we witness the vitality, variability, and creativity of populations who, in large part, live in settings characterized by racism, prejudice, and grim material realities. As we look at the specifically Islamic spatial expressions of these communities—the use of space, claims on space, the architecture of built forms, and conceptualizations of space—we encounter both patterns of everyday life and themes of the religious imagination, broadly construed.

Many observers have sought to interpret that identity through comparison to other groups marked by migration and/or religion. Dervla Murphy (1987), for example, looks to the historic experience of her fellow Irish in the north of England as the model for the South Asian Muslims in Britain today, for both groups were consigned to the drab settings of old industrial towns and both disparaged for cultural and religious difference. The Bradford Heritage Recording Unit, in a publication of historic photographs of immigrant groups to the city (1987), partly by juxtaposition of similar photographs (Ukrainian boarding house / Bengali boarding house) insists on a common pattern—now framed by the concept of “multiculturalism,” where cultural equivalences of institutions, festivals, and so forth are meant to form a harmonious whole. In the French context, Rémy Leveau (1988) has found what seem to be compelling similarities to the experience of Jews in the case of North African Muslims.

This hopeful, liberal, perspective (put at risk, Leveau suggests in his case, by contemporary French attitudes) has been questioned by some, not on the grounds of Muslim “difference,” but on the basis of what actually happened in the past. Thus, Albert Bastanier, studying the Muslim population in Belgium, wonders if the assimilation of earlier immigrants entailed “mutilation,” or if somehow an “underground” identity persisted: “Awareness of these matters required the experience of the immigration from Muslim countries” (Bastenier 1988: 134). In fact, however, the past is not an adequate guide to the present—let alone the future. The reason for that difference is not specific to Muslims.

Muslims represent a striking case of what might be called postmodern pluralism. Today’s world is one of utterly transformed communications, so that groups can at times be enmeshed in more than one country—Hispanics in the United States—or be so engaged with an ethnic or interest group—activist Sikhs, Greens—that their closest ties are to others like themselves, transcending states. The postmodern dissolution of certainties also means that assimilation and integration may no longer be perceived, even by the majority, as unquestioned goods.

The Muslims studied here are immersed in deep affective and informational networks of personal ties, organizations, and political concerns that define diverse and far-flung maps; at the same time, they are resident in nation-states whose own contours are ever more fluid. Their experiences of cultural displacement, their negotiations of hybridity and authenticity, are at the heart of contemporary life.[17] We do not know what patterns will finally emerge, but we are convinced of the importance of this moment, captured, as best we are able to do, in the words and images that follow.

Notes

1. This introduction does not attempt to survey the literature on diaspora Muslims, which is by now very extensive, but rather to set out shared themes in the papers, some of the discussion of the conference, and relevant points from the editor’s own (idiosyncratic) reading. Citations of individuals identified only by dates refer to comments made at preconference meetings listed in the acknowledgments above; comments attributed to the individuals without citation were made orally at the conference that produced this volume. In addition to the works I cite, the larger literature includes recent edited volumes by Bernard Lewis and Dominique Schnapper; Felice Dasseto; Jochen Blaschke; and Jorgen Nielsen, as well as a bibliography by Steven Vertovec (1993). (With thanks for these references to Pnina Werbner.)

2. This is the conclusion of Bruno Etienne, quoted in Markham 1988. Given the extreme French anxiety about Muslim politics, however, one wonders if interviewees might be hesitant to acknowledge any religious activity at all.

3. I am grateful to Paul Titus for helping clarify the implications of using the term space. See his “Social Space, Cultural Space, and Ethnicity in Balochistan” (paper delivered at the Western Conference of the Association of Asian Studies, Claremont, Calif., October 21, 1994). This emphasis on what people do, not only what they say, follows an approach charted by such theorists as Pierre Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens.

4. See my discussion of the possibilities of vernacular architecture in this setting as a contribution to an American Islamic architecture (Metcalf 1989). Neighbors raised objections based on noise, traffic, neighborhood homogeneity, and architecture at public hearings on the proposed mosque (cf. John Eade’s essay, chapter 12 below).

5. Clifford Geertz, oral comments at a conference to consider approaches to organizing an exhibit on Islamic cities/space (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., June 17–18, 1991).

6. These patterns may suggest the limitations of using the mosque as a focus for study of Muslim religious life (as is done in Haddad and Lummis 1987).

7. Meridian Productions produced a significant variation on this variety of films on rituals for the BBC with its “The Guests of God,” first shown June 1991. This film on hajj does indeed focus on Europe, but the central figures are converts, not migrants, and the converts are based in Germany, not England.

8. Prepared by Dr. Khalid Duran, the films emphasize the behavior of privileged participants, nostalgic about, but distant from, customary observations. Thus, “Care was taken to avoid the more popular events, which can often be outrageous.” A third film, on ‘Id al-Adha, was in fact filmed in Germany because Turkish officials feared that outmoded “bloody customs” might be included and prohibited filming in Turkey itself.

9. BHRU interview CO83, 1986. The interview itself suggests something of the alien world in which an immigrant is likely to live. With all the best will in the world, the interviewer’s very questions suggest the stereotypes widely held about Islam: they include queries about the repression of women, how the interviewee feels about the need for religious change, and whether she believes the West is more materialist than the “East.” She in fact does not buy into any of these themes: women are fine; Islam does not need to change (Muslims do), and everyone wants to live comfortably. The interviewer (or the typist), transcribing a description of the five pillars, turns the fast into “Rosa [Arabic: roza], the mother [month?] of Ramzan.”

10. For a worldly failure who, like “all Moroccans dream[ed] of getting a passport and working in Europe” (p. 88), went there from 1964 to 1973, but ultimately came back, the azan became a poignant symbol of Muslim space. “Sometimes I feel sad because I have no son and no house of my own. Then I hear the call to prayer and it washes my heart .…I was never happy working in France and Belgium because I missed hearing the call to prayer” (Munson 1984: 82).

11. Jacques Waardenburg (1988) ventures to predict a future “Islam without ethnicity” in large part as a result of the heterogeneity produced by migration, but many might doubt the likelihood of any single trajectory and expect variations depending on the contexts that emerge.

12. They are so listed on the letterhead of the Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, Selly Oak Colleges, Birmingham.

13. This is the experience of Philip Lewis, the (Anglican) bishop of Bradford’s advisor on community relations, who regularly meets ecumenically oriented visiting delegations (personal communication, July 1991).

14. On the Honeyford affair, see Murphy 1987, Kureishi 1986, and Ruthven 1990: 75–80. Yunas Samad (1991) explains the prominent role of Bradford in the Rushdie affair in large part as owed to the organization and experience of the Council of Mosques. A thinly disguised docudrama about the Honeyford affair was broadcast on British television on December 16, 1991.

15. For example, Benjamin Metcalf, then aged five, at the Playhouse School, New Delhi, 1981–82.

16. Werbner’s description of the “interhousehold women-centered spirituality,” focused on Qur’an reading and food sacrifice, among Muslims in Manchester complements Qureshi’s study of Canadian domestic rituals below (Werbner 1988).

17. The Social Science Research Council has in recent years sought to stimulate a wide range of projects on transnational phenomena (Hershberg 1992).

Works Cited

“Architecture: Prosaic Approach to the Divine.” 1990. Independent, October 17.

Asad, Talal. 1986. The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam. Center for Contemporary Arab Studies Occasional Papers Series. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

——————. 1990. “Multiculturalism and British Identity in the Wake of the Rushdie Affair.” Politics and Society 18, 4: 455–80.

Badawi, Zaki. 1981. Islam in Britain. London: Ta Ha Publishers.

——————. N.d. The Muslim College: Provisional Prospectus. London: Muslim College.

Barbulesco, Luc. “Les Radios arabes de la bande FM.” Esprit 6 (June 1985): 176–85.

“Behind the Veil.” 1989. Times (London), November 27.

Bastenier, Albert. 1988. “Islam in Belgium: Contradictions and Perspectives.” In The New Islamic Presence in Europe, ed. Gerholm and Lithman, pp. 133–45.

Bradford Heritage Recording Unit. 1986–87. Oral Histories, Catalogue, and Transcripts, Bradford Public Library. Cited as BHRU.

“Britain: On the Seamier Side.” Economist, December 7, 1991, pp. 31–32.

Diawara, Manthia. 1990. “Black British Cinema: Spectatorship and Identity Formation in Territories.” Public Culture 3, 1 (Fall): 33–48.

“La Droite refuse d’envisager un nouveau recours à l’immigration.” 1991. Le Monde, July 31.

Dunlap, David W. 1992. “A New Mosque for Manhattan, for the Twenty-First Century.” New York Times, April 26.

Duran, Khalid. 1990. “Muslims in the West: The Muslim Diaspora in Western Europe and the United States.” Typescript.

Durham, Michael. 1992. “Children from All Faiths Tell the Christmas Story.” Independent, December 14.

Eickelman, Dale F. 1989. “National Identity and Religious Discourse in Contemporary Oman.” International Journal of Islamic and Arabic Studies 6, 1: 1–20.

Eickelman, Dale F., and James Piscatori1990. Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press.

“Extremism in a Vacuum.” 1992. Independent, July 1.

al Faruqui, Isma’il. 1985. The Hijrah: The Necessity of Its. Iqamat or Vergegenwärtigung. Islamabad: National Hijrah Council.

Gardner, Katy. 1995. Global Migrants, Local Lives: Travel and Transfomation in Rural Bangladesh. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press.

Gaspard, Françoise. 1989. “Pensons aux musulmanes qui se battent!” Le Nouvel Observateur, October 26–November 1, pp. 79–80.

Gerholm, Tomas, and Yngve Georg Lithman, eds. 1988. The New Islamic Presence in Europe. New York: Mansell.

Grabar, Oleg. 1983. “Symbols and Signs in Islamic Architecture.” In Architecture and Community: Building in the Islamic World Today, ed. Holod, pp. 25–32. Aga Khan Awards for Architecture. Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture.

Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, and Adair T. Lummis. 1987. Islamic Values. in the United States: A Cooperative Study. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hershberg, Eric. 1992. “An Agenda for Transnational and Comparative Research.” Items 27 (June/September 1992): 27–30.

Hoffmann, Stanley. 1992. “France Self-Destructs.” New York Review of Books, May 28, pp. 25–30.

Holod, Renata, ed. 1983. Architecture and Community: Building in the Islamic World Today. Aga Khan Awards for Architecture. Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture.

Kastoriano, Riva. 1987. “Definition des frontières de l’identité: Turcs musulmans.” Revue française de science politique 37, 6 (December): 833–54.

Kepel, Gilles. 1989. “L’Integration suppose que soit brisée la logique communautaire.” Le Monde, November 30.

Kettani, M[uhammad] Ali. 1980. “The Problems of Muslim Minorities and Their Solutions.” In Muslim Communities in Non-Muslim States, pp. 91–108. London: Islamic Council of Europe.

Kureishi, Hanif. 1986. “Bradford.” Granta 20 (Winter): 149–70.

Larson, Heidi. 1990. “Culture at Play: Pakistani Children, British Childhood.” Ph.D. Diss., Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley.

Leveau, Remy. 1988. “The Islamic Presence in France.” In The New Islamic Presence in Europe, ed. Gerholm and Lithman, pp. 107–22.

Lewis, Philip. 1994. Islamic Britain: Religion, Politics and Id. entity among British Muslims. London: I. B. Tauris.

Markham, James M. 1988. “If the Racism Tastes Sour, How Sweet Is Success.” New York Times, November 16.

Masud, Muhammad Khalid. 1990. “The Obligation to Migrate: The Doctrine of the Hijra in Islamic Law.” In Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination, ed. Eickelman and Piscatori.

Metcalf, Barbara. 1989. “Chapel Hill Mosque Should Utilize Local Culture to Express Distinctiveness of Islam.” Chapel Hill Newspaper, November 26.

Miller, Judith. 1991. “Strangers at the Gate: Europe’s Immigration Crisis.” New York Times Magazine, September 15, pp. 32–38, 49, 80–81, 86.

“Minaret Is Silent, but Has Much to Say to France.” 1990. New York Times, November 29.

Mirza, Kausar. 1989. The Silent Cry: Second-Generation Bradford Muslim Women Speak. Muslims in Europe #43. Birmingham: Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations.

Munson, Henry, Jr., trans. and ed. 1984. The House of Si Abd Allah: The Oral History of a Moroccan Family. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Murphy, Dervla. 1987. Tales from Two Cities: Travels of Another Sort. London: Penguin Books.

“Muslim Fast in U.S. Holds Difficulties.” 1992. New York Times, March 6.

“Muslims Open ‘Parliament’ with Defiance.” 1992. Independent, May 5.

Poston, Larry. 1992. Islamic Da‘wa in the West: Muslim Missionary Activity and the Dynamics of Conversion to Islam. New York: Oxford University Press.

Riding, Alan. 1991. “France Sees Integration as Answer to View of Immigrants as ‘Taking Over.’” New York Times, March 24.

Robinson, Francis, ed. Forthcoming. The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World.

Rouse, Roger. 1991. “Mexican Migration and the Social Spaces of Modernity,” Diaspora 1, 1 (Spring 1991): 8–23.

Ruthven, Malise. 1990. A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Rage of Islam. London: Chatto & Windus.

Samad, Yunas. 1991. “Book Burning and Race Relations: Political Mobilization of Bradford Muslims.” St Antony’s College, Oxford. Typescript.

Schiffauer, Werner. 1988. “Migration and Religiousness.” In The New Islamic Presence in Europe, ed. Gerholm and Lithman, pp. 146–58.

Shaw, Alison. 1988. A Pakistani Community in Britain. Oxford: Blackwell.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Silverman, Maxim. 1991. “Citizenship and the Nation-State in France.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 14, 3 (July): 333–49.

“6000 U.S. Muslims Meet; The Enemy: Stereotypes.” 1990. New York Times, September 3.

Starrett, Gregory. 1992. “Our Children and Our Youth: Religious Education and Political Authority in Mubarak’s Egypt.” Ph.D. diss., Department of Anthropology, Stanford University

“TV Introduces West Germans to Islam.” Arabia, November 1984, pp. 87, 91.

Vertovec, Steven. 1993. Annotated Bibliography of Academic Publications Regarding Islam and Muslims in the United Kingdom, 1985–1992.Bibliographies in Ethnic Relations, 11. Coventry: Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick.

Waardenburg, Jacques. 1988. “The Institutionalization of Islam in the Netherlands, 1961–86.” In The New Islamic Presence in Europe, ed. Gerholm and Lithman, pp. 8–31.

Werbner, Pnina. 1988. “‘Sealing’ the Koran: Offering and Sacrifice among Pakistani Labour Migrants.” Cultural Dynamics 1, 1: 77–97.

——————. Forthcoming. “Diaspora and Millennium: Islamic Narrations, Identity Politics, and the Aesthetics of the Religious Imagination.”