PART TWO

SETTLED IN CHENGTU

8

Mount Omei Summer

(1906)

On May 10 we entered Chengtu and proceeded along the Great East Street, the city's chief thoroughfare. It was considerably more imposing than any street we had previously seen in a Chinese city. We had reached our goal. It was a momentous day, saddened only by the thoughts of our precious Virginia.

As the Friends were having a gathering of their mission, we were to be entertained temporarily in the home of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Beech of the American Methodist Mission. However, we first went with Warburton and Hetty to the Friends' compound,[1] where we met Dr. and Mrs. Hodgkin and were welcomed by them and the elder Davidsons, "R.J." and "M.J." We stayed only a few minutes and then went on to the Methodist compound where we had another warm welcome from the Beeches. Their little Margaret was being carried by an amah with bound feet. I was stricken at the sight and felt this must be a frightful ordeal. I soon discovered that thousands, indeed millions, of women in China suffer this way all their lives. Now the custom is dying, but it still is not eradicated.

Dr. and Mrs. Canright lived in another house in the Methodist compound, and near by were the rising walls of the missions new hospital. Mr. and Mrs. Openshaw of the American Baptist Mission in Yachow, four days travel to the west, were visiting in the Canright home. All these foreigners came in that evening to welcome us and hear of our travel. It was almost six months since we left California, and we had undergone a good deal in the way of experience.

Here at the Beech home we were in a foreign house built in a semi-Chinese manner. The upper rooms were low with slanting ceilings. A ve-

[1] "Compound" is the term generally used for a walled enclosure within which foreigners live. It comes from a Malay word, kampong . In China one did not speak of a Chinese compound: it was always a place where foreigners lived—within walls.

11

"Within a few days Bob seated himself at a small bamboo table on

a cornerof this veranda. Opposite him was a Chinese teacher named

Yeh. There began the long pull at language study."

randa surrounded the lower floor. Within a few days Bob seated himself at a small bamboo table on a corner of this veranda. Opposite him was a Chinese teacher named Yeh. There began the long pull at language study which has to pave the way for understanding and work in the land of Cathay. At that time there were no formal language schools. The trial and error system was largely used, and one had little help in grammar and in mastering the elusive tones. Our teacher spoke the Szechwan variety of Mandarin and we were thankful to make a start. I studied also, but very soon began to have attacks of sharp abdominal pain. These left me weak and with little ambition for anything.

After a fortnight we moved over to the Hodgkin residence, where we had an upper east bedroom with veranda. The two Friends families gave a large reception for us. Both Hodgkin and Davidson houses were open and we spent part of our time in each house. The weather was warm, the flower gardens were lovely, and most of Chengtu's foreign community of about fifty people turned out to meet us.

Bob continued his study on the Hodgkin veranda, and I continued having attacks of pain. Before June was far gone, three foreign doctors had a consultation regarding my problem. The pain, they decided, was neuralgia of the stomach, and I was given spirits of ether to allay it. Also, everyone agreed that we should get away for the summer.

Arrangements were made for us to travel to Mount Omei with Laura Hambley of the Canadian Methodist Mission and Helen Witte of the Ameri-

can Methodists. Miss Hambley had not been out [in China] long, but she knew enough of the language to manage the party. Miss Witte had arrived only a few months before us. The pleasure and profit of our first summer was largely due to these two fine friends, particularly to Laura Hambley whose kind thought had suggested that we accompany them and share living arrangements.

We had a small mat-roofed boat for the trip on the Min River to Kiating.[2] The. ladies had another; the two boats were to keep together all the time. There were numerous vicissitudes on the journey. Mosquitoes were terrible in Kiating. There we left the river and took sedan chairs for a day and a half to Tawosze, a temple on the flank of the sacred mountain, Omei Shan. The mountain itself is over 11,000 feet in elevation, but the temple is at about 2,700 feet. After a miserable night in an inn at the foot of the mountain, we started up the lower slopes of the mountain to the temple.

Miss Witte was so sorry for her chair bearers on a steep grade of rough steps that she got out to walk, Her men then hustled along and soon had such a lead that they could not hear her calling them to wait for her. Of course, they knew that she now wished to ride; but preferring to carry an empty chair, they tarried for nothing. Finally, Bob had to push ahead and overtake them. By the time she got in, Miss Witte was so exhausted by the heat that she announced she would ride no matter how steep the road. Naturally, we were not accustomed to be carried up long, steep flights of rough-hewn steps; so we did have great sympathy for the bearers; and they played up to our compassion. After many similar trips we became used to such travel. We always did what we could to relieve the men. I was content to ride most of the time, but as I weighed only about one hundred pounds, I was not an excessive burden for three or four men. Bob did his climbing on his own feet.

At Tawosze we had two rooms at one side off one of the lower entrance courts. Everything was Chinese save our cots with bedding and mosquito nets. We also had two folding canvas armchairs made after a British army model. We used a square temple table for study and had some heavy wooden chairs that belonged with the rooms. Laura and Helen, our companions, had a larger suite of rooms on the opposite side of the same courtyard, and the four of us combined our eating arrangements. Laura had brought the cook, so she managed him for the first few days; then Helen took her turn; finally I, in my first few stumbling Mandarin words, tried to give directions for meals.

[2] The Min River between Chengtu and Kiating is, by comparison with the Yangtze, a small and shallow stream. So the Boat by which Bob and Grace traveled was much smaller and simpler than the stately houseboat of the Gorges. It was what the Chinese called a wuban ; apart from its smaller size, it lacked the high stern of the Yangtze junk. The trip from Chengtu to Kiating probably took two or three days. Kiating is now known as Leshan.

The cook had never been much more than a table boy and knew little about cooking. Our fare was plain and simple. Helen had an amah, and we a coolie, so there was plenty of help.

All four of us were studying Chinese, but Bob kept at it more consistently than I. The climate seemed to make us sleepy, and we usually took naps after the noon meal. In the late afternoons there were hikes around the temple purlieus, or tennis in the upper stone-paved court in front of the main building. Some thirty-five foreigners were at Tawosze that season. We made many friends and had a jolly time, with picnics to the Flying Bridges and other scenic parts of the mountain, and tennis matches at the temple when there were not too many hui . This particular kind of hui is a gathering of friends or neighbors who visit the temple for collective worship toward some specific end. These groups would arrive in long processions with many banners, firecrackers, and incense. The whole place would be overrun with the worship-pets, who were usually delighted with the unexpected extra benefit of seeing us, our rooms, and our peculiar ways.[3]

We became well acquainted with Dr. Florence O'Donnell at the temple that summer. She stayed with friends and occupied a room just above our sleeping room. As only rough floor boards separated us, we could hear her every step. When she took a bath, we frequently participated to the extent of a mild shower. Of course, in those temple rooms we had no conveniences and lived in camping style; but we did have portable galvanized bathtubs of oval shape into which the coolie would pour a bucket or two of water. We carried these to the mountain, and there in the temple they proved luxurious indeed.

[3] Grace followed the usual habit of referring to any Chinese religious building as a temple, and those attached to them as priests. There were differences, in both faith and function. Tawosze, as indicated by the sze in its name, was a Buddhist monastery.

In these early days, the foreigners had not yet developed their own summer resorts. In their belief that it was essential for health reasons to get away from the oppressive heat and summer pestilences of the plains, mountain monasteries were a favorite choice. They were usually in a place of quiet isolation, purposely away from large towns. They were almost always in a situation of natural beauty. It was a beauty which their own presence and great age enhanced. One chief reason was that it was only in temple grounds, and on immediately adjacent temple property, that one could see groves of mature, majestic trees. Also, these monasteries were objects of pilgrimage and places where scholars and literati were fond of relaxing close to nature. So the monasteries often had extensive, if simple, accommodations for guests. The abbots in charge apparently had no objection to renting these to apostles of a rival faith.

Relations may have been economic, but faith could not be wholly ignored. Being a monastery, there was always a resident community of monks—whose numbers were governed by the size, prestige, and prosperity of the institution. And the monks, like monks everywhere, had their daily round of religious services. We boys were probably more interested in these than were our elders. The very early morning, soon after dawn, was a good time—as one lay in bed—to hear the deep, unintelligible chanting of the sutras, punctuated now and then by a low-voiced bell or a drum, or the hollow sound of the wooden fish. Of course, the missionaries had their own prayer meetings and religious services on monastery premises—but these were more somber in nature.

During this summer I had the only attack of malaria that I had in China and was in bed for several days. Miss Wilkins, then of the Canadian Mission, was the trained nurse who helped me. How wonderfully she rubbed my aches and pains away! The Canadian ladies of Kiating had brought their own cows up onto the mountain and so were the only people who had fresh milk. They kindly sent me several cups each day while I was sick.

I wrote my mother about this friendly act. As she was always very ardent against cruelty to animals, she at once wrote back that she thought it terrible to take cows up to such places by roads which had flights of steps. In fact, she was thoroughly aroused by this innocent action of the missionary ladies. As we had seen plenty of horses scrambling with riders or heavy loads up the slippery, wet stone steps at Chungking's city gates, a leisurely mountain climb to Tawosze did not seem so bad to us. I wrote Mother how the Chinese outfitted cows and even pigs with straw sandals for such trips, to save their hoofs and prevent slipping on the steps. I also told her of the way pigs are often carried to market in slings made of bamboo slats, each piggy borne by two carriers. Of course, this was after the porker was fattened for sale and was intended to prevent the loss of a pound or two en route to the knife. Still, it gave the pig a ride and showed thought on the owner's part.

Mother was unimpressed. Her last remark in this months-long discussion was to the effect that I had already become hardened to ways that would shock and horrify in America. Five to six months was the normal time for an exchange of letters between Szechwan and California; one almost forgot the question before the reply came back. As to pigs, we have frequently seen them carried in odd ways. As recently as three years ago, riding on North Szechwan Road in a Shanghai ricksha, I suddenly found myself abreast of another ricksha in which rode two well-grown black pigs. One was on the seat, the other on the little foot platform.

An important event of the summer was a trip to Mount Omei's Golden Summit. We joined a party of friends. The intent was to travel simply, but of course we had to take beds and food. We went up the small road called "the ninety-nine turns" and returned to Tawosze by the "big road." The lower section of the small road above the Flying Bridges partly followed the bed of a stream, and the coolies carrying my chair often had to step from rock to rock with water rushing between them. Later the canyon became so narrow that there was no space for foot of man or beast. There we mounted a somewhat rickety "bridge" running lengthwise of the stream. Beams set in sockets cut into the rock walls supported a pathway of rough planks along one side of the gorge. Some of the ninety-nine turns were so sharp and steep that even my simple mountain chair with skillful mountain carriers could not negotiate them until Bob got in between the poles and lifted at the critical moments.

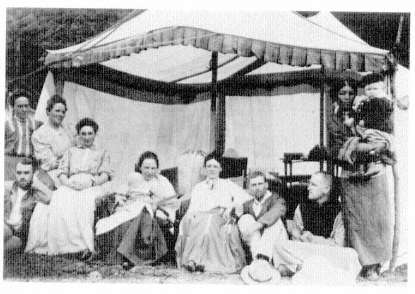

12

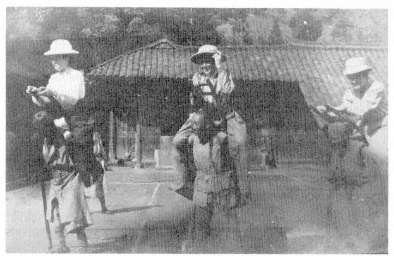

This is the type of "mountain chair" that Grace used for her mountaineering trips.

(The actual occupant here is unknown.)

We spent a night at Nine Old Caves, staying in the excellent temple and visiting the outer part of the caves. These were damp and slippery, and full of bats swooping about us. We did not go far in, much preferring the beautiful verdure of the mountainside. Here at this temple, a green-clad cliff hung with ferns, creepers, orchids, and lovely wild begonias was a delectable sight.

Going on, we took in all the pleasures of a slow climb. Because Golden Summit is slightly over 11,000 feet, the temperature change from Tawosze is considerable. Vegetation runs riot all over the mountain. Ferns, rhododendrons, laurels, hydrangeas, and a myriad other species of shrub, flower, and tree delight one's senses at every turn. In clear weather one gets a magnificent panorama from the Golden Summit; the mighty snow peaks of the Tibetan border can be seen in all their glory. We were fortunate to have an unbroken view of the whole line of peaks, a breathtaking sight.

As soon as we reached Golden Summit late one afternoon, our Boy urged us to hurry to the platform at the edge of the great precipice. Here on one side we saw the snow mountains; and on the other side, the setting sun being low in the sky, we beheld our enlarged shadows, heads encircled with rainbow hues, thrown on the clouds below the cliff. A priest standing by assured us that only the good saw this much-desired sight. The phenomenon is similar to the Spectre of the Brocken, seen in the Harz Mountains; at Omei it is known as Foguang (Buddha's glory). Buddhists claim it is light from the aureole of Buddha and a sign of the holiness of the place. Pilgrims wrought up by reli-

gious zeal have thrown themselves over this three-thousand-foot precipice to meet the Buddha; to deter others, a railing is fixed at the cliff's edge.

On the trip down from Golden Summit the Big Road gave us new sights and more extended mountain vistas, as this road follows wider canyons. We also met many ascending pilgrims who choose the larger road because of its better steps and more gradual ascent. Among these were women, frequently with bound feet, who hired men to carry them up the mountain. Loads in these hilly areas are carried on V-shaped wooden back-frames. A passenger sits atop this frame on a couple of wooden slats. This puts him (her) facing in the same direction as the carrier, with knees just above his shoulders. The bearer is equipped with a sturdy crutch-stick like a third leg, When they stop to rest, they place the crutch-stick under the back-frame, lean back to ease themselves of the weight, and catch a brief respite from the heavy toil of the journey. At this time they expel their breath with a peculiar whistling sound. This apparently helps to revive their flagging spirits as well as their weary muscles. On the twisting road one often heard this whistle and knew that a loaded man was resting; sure enough, as one rounded the curve, he would come in view.

At Tawosze, Dr. C. W. Service had a little clinic. As he returned from a trip

13

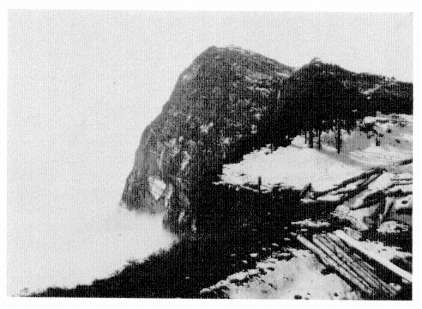

The "Golden Summit" of Omei, the sacred mountain. Along the crest are

pilgrimage temples. "Buddha's glory" appears, when conditions are right, on the

cloudbank at the left below the great precipice.

14

Back-frames for mountain travel. On Mount Omei about 1907.

to Golden Summit, he heard that a young priest on the upper mountain had been badly mauled by a leopard. Because this was considered to be punishment for his sins, he was turned out of his temple. Nobody would help him, and he was lying helpless and abandoned in a rude bamboo hut. When Charlie [Dr. Service] saw his plight, he asked for him to be put on a beizi [carrying frame] and brought to his clinic. No one was willing to do even this, but Charlie finally persuaded a carrier to bring the wounded man down.

I heard about the affair and suddenly felt a great desire to see the doctor at work. The Chinese assistants had tried to clean up the man but he was a sad sight; dirty, worn with fatigue, and his body covered with itch. He wore only ragged pants, and some bloody scraps of old matting were tied around his body and arm. The wounds were chiefly around the left elbow. In the course of the doctor's cleaning the terrible-looking wounds some solution was used in a syringe. When I saw this liquid going in one opening above the elbow and coming out from two holes, one slightly above the elbow and another below it, I began to feel queerly. One of the Chinese assistants pointed to an open door. I went out and sat down on some steps rising from a small court. The next I knew, I was pushing a big bottle of ammonia from under my nose. The man recovered and became another medical triumph for the hardworking mission doctor, who found need on every side, even on his summer holidays.

Bob made another excursion to Golden Summit, this time with Mr. Manly, to do some exploring. They went to Nine Old Caves and around under the face of the great perpendicular cliff, hoping to be able to get up that way. They found no feasible route; but, scrambling up the side canyon, they fi-

nally came on a charcoal burner's trail and were able to ascend by it to the main ridge of the mountain. On the afternoon of their return after three days of strenuous climbing, Bob took a quick sponge-off and was soon on the tennis court, ready for a set. On his trip he had worn a blue woolen shirt from which the color ran; his white skin was dyed in streaks which did not come off for weeks. He began collecting butterflies this summer and found it an absorbing and interesting avocation.

The summer was not without its romance. Mr. Taylor of Yachow was frequently at our temple rooms for tea. And the tea, of course, was always in the suite of the Misses Hambley and Witte. Helen Witte was very coy, but we all saw how things were going. We jocularly referred to the courting gentleman as "Grey Legs" because of his favorite color in trousers, but this name was never applied to him in person. A mention of his nickname would make Helen blush. Bob and I left Tawosze the day before Laura and Helen. As I left the temple in my chair, I said good-bye to Helen, telling her to look well after Grey Legs, who would soon be lonesome in Yachow. She flushed deeply and burst out: "I'm so glad you know about us; we were wanting to tell you." So the cat was out of the bag! Alas, I was in a poor frame of mind to meet Dr. O'Donnell. She had told me she was sure the two were engaged; but I had said no, and that I'd eat my hat if they were. My only hat on the trip was a sun topee.

9

Our Own Home

(1907)

Back in Chengtu we were soon house hunting. The Friends were willing to let us have land for a house; but we had been told by the YMCA to rent, that there was no money to buy or build. It was difficult to find any suitable place, or one that we could rent if it were suitable. Chinese do not always care to rent to foreign tenants whose ideas of house arrangement and fitments were so different from their own. Mr. Beech finally came to our assistance. The [American] Methodist Episcopal Mission owned a property on a street named Wenmiaogai,[1] in the southwest part of the city, where it conducted a middle school for boys. It was expected that the school would grow and eventually need a larger place. To the west of the school was a temple.[2] To the east there was a Chinese residence property. This offered the only solution for the school's expansion. Mr. Beech proposed that the mission buy and lease it to the Y until needed by the school. The mission would have its room for growth, and a present income.

Mr. Beech took us both with him when he went to look at the property. The men insisted that I accompany them so I could penetrate into the women's quarters. Of all the places we had seen, this seemed the most satisfactory, though the rooms I saw were filthy and dark. Our vision looked into the future and saw fresh, clean walls, glass windows, and other foreign additions for comfort and convenience. After long talks and negotiations through a middleman, the purchase was at last complete. Next was a long interval until the owners could move. Then there had to be a mighty cleaning. Finally, we moved, bag and baggage, into the new premises.

[1] Gai in the name means "street." It is the Szechwanese pronunciation of the character jie .

[2] The temple was the local government's temple to Confucius. Its Chinese name was Wenmiao, "Temple of Learning." Because our street was the one on which the temple stood, the street was Temple of Learning Street. The temple helped to make it a good neighborhood and had some fine trees.

A rather imposing front gate opened into a forecourt. Crosswise in this court was a handsome spirit screen. At each side there was access to a small side court. These provided space for the gateman and his family, servants' living quarters, and a stable. Across the north side of the forecourt was an open structure, a sort of pavilion, or tingzi . This was convenient for sedan chairs. Passing through this pavilion, one entered a brick-paved upper court. There were rooms opening off each side and in the pavilion. Across the north side of this court was the main residence. This was a single-story building in the local Szechwan style and five jian long.[3]

We signed a lease for the property. The mission agreed to pay for lumber and materials for the needed alterations. The YMCA was to pay for the labor. We moved into the rooms on either side of the tingzi . The large room on the east was our living room; the corresponding room on the west was our bedroom. The windows were paper, the doors anything but tight. Luckily it was a record winter for warm, sunny days. Great was the excitement at opening boxes the contents of which we had never seen. Some of our household equipment had been ordered in the spring of 1905; it was now the fall of 1906.

The Ladies' Home Journal in those days had many pictures of house interiors. From them we gleaned many suggestions. Our front hall, with a landing halfway up the stairs and a door under this, was copied from such an illustration. The rooms at the two sides of the upper court were torn down and the material was used to expand the main residence. Both ends of the building were widened and a second story, for bedrooms, was added. What had been a long, single-story structure connected to the side buildings of a court now became an H-shaped, free-standing, two-storied, semiforeign house. Most rooms were Chinese lath and plaster, but there was a wooden wainscoting in the study, and the dining room was panelled in wood. The kitchen was at the back but within the main house. Most people had detached kitchens, so ours was considered a novelty. Of course it lacked any built-in cabinets. But we had plenty of cupboards made according to my plan. Table tops were finished in glistening black varnish with the tung oil base that is now so much in demand abroad.[4]

There was no one to manage the workmen but Bob; no one to show the masons how to construct a brick fireplace and chimney but Bob. He was kept busy all day, often finding his limitations of language most trying. What we did not know about house construction or domestic management we had to learn, and were glad of advice by those who had been through similar

[3] A jian , often translated "room," is the standard space between pillars in Chinese residential construction. My memory guesses that it is about eleven or twelve feet.

[4] Tung oil, or wood oil, comes from the kernel of a tree that is widely grown in East Szechwan. Before the day of synthetics it provided the base for the best varnishes and used to be a major Szechwan export.

experiences. To our youthful enthusiasm, everything moved at a snails' pace; still, there was progress. Early in 1907 we began to move into the house proper.

The sewing machine whirred hour after hour as I made curtains for every one of the new windows, which boasted so much glass that our Chinese friends were amazed. Next to the glass of our small casements in the big south bay of our living room hung little, ruffled, white dotted-swiss curtains looped back at the sides. Over-drapes were of a soft, rather heavy blue silk figured in a woven geometric design. (This material was later dyed and re-dyed until I finally gave it away in Tsingtao in 1934, still not in any way worn out.) On the floor of this room we put our tan and blue Tientsin carpet. How we danced about on this when it was unpacked and spread on the floor! On my birthday Bob gave me a cute little tea-table with a shelf. He had designed this himself and had it made by a carpenter on the place without my knowledge. What a joy it was to move into a clean, second-floor bedroom with nicely oiled floor, large casement windows, a clothes closet, and an adjoining bathroom with convenient backstairs for the carrying of bath water![5]

I was having attacks of severe abdominal pain every now and then. When a paroxysm hit I would hope I'd never live to experience another. Sometimes I seemed to lose my eyesight and could only feel for Bob's hand in my keen distress. We both tried to study as we could, and the teacher came regularly; but I was busy teaching absolutely green servants, and Bob had to be vigilant with the workmen. His neglect might mean a waste of time or material. But any negligence on my part might mean contamination of our food and consequent illness. I had to be on my job.

Looking back, I have seen many excellent servants to whom one can trust the details of foreign kitchens, but their care and method has been learned in the school of eternal vigilance during their training. To tell a Boy once to do a thing is never enough.[6] The perpetual daily alertness of the mistress, the repetition of instructions over many months is what finally produces care in the hygienic preparation of our food and the cleaning of our rooms. I have frequently heard women exclaim over stupid servants, saying that it is impossible to train them. There are some impossible to train, but usually it is the mistress who lacks the patience or will not take the time.

[5] Our family lived in this house until 1920. All three of us boys were born there. Since I lived in it for the first eleven years of my life, and relatively short times in other places, I always thought of it as "home." When Caroline and I were invited to return to China in 1971, we visited Chengtu and I asked to visit the house. Where we had lived, there resided some twelve families. The whole place had deteriorated sadly. And it seemed much smaller than I had remembered it! By 1984 the whole compound had been torn down and the site covered with rather nondescript modern buildings. The Temple of Learning had disappeared long before.

[6] When the word "Boy" is capitalized, it will refer to the servant, often of mature age and great dignity, who waits on the table and, depending on the household, fills the role of major-domo or butler. A lower-case "boy" is simply a young lad.

After our return from Mount Omei we had to assemble some servants. There were none to be had who could boast any foreign training, but we did try to find men about whom something was known. The cook was a young man known to the Davidsons. The table-boy was a chap who had been a Yangtze tracker. He was young for that hard life and had been brought to Chengtu by one of the Canadian missionaries. We took him, but he had no suitable clothes, and we agreed to buy the usual long cotton gowns. He was to purchase three, and we gave him the money to pay for them.

One day soon afterward there was a great commotion at our front gate. A man was crying to the gateman that we owed him money. Bob went out and discovered that it was the tailor who had made the Boy's three gowns. As we had already given the Boy this money, he was called and had to admit the debt to the tailor. However, he said he had no money. Bob could not have the tailor suffer for our servant's trickery, so he told the man that we would pay him but that the Boy would have to settle with us. This made the Boy exceedingly angry. Realizing that he had lost much face, he flew into a violent, black rage. In a trice, his face turned livid like that of a fury. He threw himself on Bob, yelling, muttering, spitting in his wrath. He seized Bob by the throat and pulled his necktie tight like a noose with his left hand while he struck out with his right in no gentle manner. Bob kept pulling at his collar, trying to loosen it, while he warded off blows. He did not attempt to strike back. Finally the man hit below the belt in a very menacing way.

I had run into the tingzi to find out what was going on. Bob called to me to stay well away; it was impossible to know what the man might do. The gateman had run for the policeman at our corner. This worthy came, but did nothing save look on. A large crowd soon collected at our gate, attracted by the Boy's loud cries that a foreigner was killing a Chinese. But all near enough to see could tell that Bob was not the aggressor. At last, the Boy was prevailed on to leave off his attack. He was then arrested and taken off by the policeman. I had to cut Bob's necktie off. The knot was so tight that it was impossible to untie even when cut free. The man stayed in jail for a week or two and then Bob sent his card to have him let out, Naturally, we did not want to have him working for us. But his old clothes had disappeared so we let him make his departure in one of the new gowns.

This is the only time Bob was ever attacked by any Chinese. By keeping cool and refraining from retaliation, he had all the spectators with him. They saw he had done nothing to warrant the attack. Some of our neighbors (Chinese, of course) spoke later to him and to our gateman about the affair, saying that the Boy had behaved in a very bad manner and that Bob had only defended himself as anyone would. His actions that day won him a place in our whole neighborhood.

Christmas we celebrated quietly at the Canright home on Christmas eve-

ning with the members of the Methodist Mission. We had nuts, fruits, and candy; and enjoyed old-fashioned pastimes such as "Spin-the-platter" and guessing contests. Mr. Joseph Taylor came over from Yachow that winter and married Miss Witte; we saw "Grey Legs" and Helen through the ceremony. This was the first wedding we attended in China. During that winter Archibald Bullock [UC 1906] arrived from California to teach in the government university only a short way down the street from us. He was from Berkeley and had been among the college crowd who saw us off for China. We saw him frequently and liked having him as a neighbor.

In the spring of 1907 I became friendly with the wife of the British consul and used to enjoy her visits. Sometimes she came in the forenoon and we had "elevenses"—cocoa or tea with a biscuit or sandwich. She even helped me hemstitch pongee curtains for the study. Florence O'Donnell was another good friend (we still keep up a correspondence though she left China in 1908). What fun we used to have at dinner parties in those days! Charades were greatly favored by the British. I shall never forget some of them trying to act out words such as "serviceability," "transportation," and "hospitality."

But through all this, our chief concern was to become acquainted with Chinese, particularly the university students who lived near us. One of our friends was Dr. T. Z. Koo, then a young instructor in the government university.[7] Students and other young men soon began to come around to call and to make friends. Sometimes, we realized, it was mainly to get some practice in English. Bob was constantly meeting new students and finally gathered a group for discussion. They delighted in choosing English names for themselves—such as Lincoln, Bismarck, or Solomon. Often they came to our house for games: tennis, quoits, checkers, and such amusements.

After we settled into our little Chinese house, the rest of 1907 was mostly given to language study. We had few foreign neighbors. The teachers at the government university (three or four were foreigners) were only half a block away; the American Methodists were fifteen minutes by chair. Though we had been told we would be too far away from other foreigners to see much of them, we found that friends came to see us in spite of distance. It was almost an hour's trip over to the Canadian corner of the city, so we could not go there very often.

In the spring of 1907, when I was at my wit's end with the everlasting noise of workmen in our small compound, Bob had sent me over to spend a fortnight with the Canadian ladies. On my return I missed several things

[7] T. Z. Koo became head of student work for the YMCA in China and then became prominent in the international YMCA movement. That Chinese were able to become leaders of the organization in China and then move into a broader international role was one of the differences between the Y and the church-controlled missions.

around the house, the most important being a slender gold chain and a gold locket given by my mother to our baby. I should never have left them in a drawer; but evidently I did, and they were never seen again. There had been a few other thievings earlier, but nothing of moment. I was not well that spring; my severe pain came back; and finally I was upset by a more serious robbery.

We had no safe place to keep our money; of necessity, we had to use suitcases and trunks with foreign locks. We obtained silver dollars by selling Shanghai drafts, usually through the Post Office. There were fifty silver dollars in a roll; they usually came in packages of two rolls, or a hundred dollars. We had been locking these in our sturdiest leather suitcase which was kept in the closet off our bedroom. One May evening we were entertaining the British consul with his wife and some other friends at dinner. While our guests were in the house, we were with them on the ground floor. It must have been during this time that the robbery occurred. We had seen that the money was there during the day. The morning after the dinner, one of us unlocked the suitcase. The steel frame of the case had been forced so that a hand could be inserted. Nearly one hundred dollars were missing.

Such a robbery could not be allowed to go unnoticed. We had to call in the police. They marched all the house servants off—on a day when I had to go to bed ill and a hurry call was sent to the doctor. I lost my hopes of a baby expected for that autumn. I lay for three weeks flat on my back, not even a pillow under my head. Bob had everything to do: cooking, nursing, and all. I had fainting spells and needed to be watched, so he was tied to my bedside. The Methodist ladies took our laundry. They also sent us bread from time to time. The gateman could buy eggs and a few supplies near by; but since there were no other servants to tend the gate, he could not go far. I feel into a sad despondency and wept more than I had ever wept before. Bob was much distressed; the gateman offered sympathy, telling Bob that a woman would often cry a great deal after such a loss. The gateman knew life.

At this juncture, a young man appeared at the gate and offered to work for us. He had been with us for a while a year before but could not get along with the amah we then had. Now, with the amah and all our other servants gone, we gladly took him back. Gradually, other servants were found. The police could not identify our thief, and we did not want to keep the arrested servants in jail indefinitely. Bob finally asked for their release. We could not, however, reemploy them. So the work of training new helpers had to be started all over again.

10

Again to Omei

(1907)

I was still very weak after I got up. It was decided that we should go back to Mount Omei, to Tawosze temple again, for the summer. The first time I went outside the compound gate after my illness was when I rode my chair to our small river boat to start this trip. This time we traveled alone. In Kiating we had another terrific time with mosquitoes. We stayed in the empty house of the Canadian ladies. After we let down our net, these pests came up through a crack in the head of the bed. I doubt if we got half an hour's unbroken sleep that night.

As before, we left our boat at Kiating to proceed by chair to the mountain temple. The Ya River had to be crossed by a ferry. The river was badly swollen and the sky threatened more rain, so we were anxious to hurry on. Bob had to await some of our loads that had fallen behind. I got into the ferryboat with my sedan chair and bearers, the Boy, and a part of our baggage, leaving Bob to come across as soon as he could. Not until we were well out in the stream did I notice how high the waves were running. As we neared the farther bank and were unable to make the usual landing place, I began to see the distress of the boatmen. Our small boat tore along down stream at an alarming rate and they were not able to control it. We were past the gravelly landing and were threatened by large sections of the soft earth bank that were being undercut by the flood and falling into the water. I saw there was fear of our capsizing as the rising wind caught us broadside, so I got out of the sedan chair, freed myself from the boxes and carrying poles, and stood with my arms out of the sleeves of my raincoat. The Boy turned that ashy green which Chinese skin is apt to assume instead of our white pallor of fear. Just as things were looking worse than ever, and a crowd of people on the shore were yelling to us to put back, we saw a small cove where a tiny stream entered the river. Quickly the boatmen shoved with all

their might on the oars and succeeded in pushing the nose of our boat into this haven. Men on shore seized ropes and held us secure. Bob crossed safely on the next trip.

Some days later I wrote an account of this trip in a letter to my parents. Bob asked if he might read it. When he had done so, he asked me as a favor not to send it. I had not thought of how it might strike my father and mother. Bob was always very careful of me, but this could look as though he had been careless of my safety. I changed the account before the letter was posted.

At Tawosze this summer we had a suite upstairs on the north side, on the same level as the tennis court. There was a large living room with a lot of exposed rafters overhead. The bedroom was smaller; and the kitchen scarce merited the name. It was merely a place where one could cook on a makeshift native stove. To it, a dark passage led from our living room. All windows had wooden shutters only, no glass. They were left open and we had plenty of air. If rain came from the north, the shutters on that side had to be closed. The south windows gave onto a veranda, so could always remain open. We hung a few curtains in one corner of the bedroom to make a little private nook for baths and dressing.

We had the same Boy who had come to us in Chengtu when I lay so ill. He acted as a general factotum and was devoted to us. There was also a cook—of a sort. He was the best we could find for the summer. Bob made me promise that I would not go into the kitchen, no matter what happened. I really kept the promise until some weeks after our arrival when we were preparing for another trip to Golden Summit. I happened to venture to the kitchen in search of something the cook could not locate. Our chef, I discovered, had been sweeping all rubbish, including empty food tins, under the rough kitchen table. That heap of refuse was an awful sight for a neat housekeeper! I was not very strong, but I made some metaphorical fur fly.

The Boy was fond of flowers and constantly went out on the mountain-side, bringing back hydrangeas, lilies, begonias in lovely profusion, and many other blooms. He also gathered ferns, roots and all, and fashioned hanging baskets so covered with moss and so filled with drooping ferns that one could not see their bamboo framework. We hung these verdant little baskets on our veranda and in our living room until our place was like a bower.

Bob had swung our big red-striped American hammock from the rafters of the living room, and I spent a great deal of time in it. He also kept two chair bearers for me, as I had no strength for walks or climbs. We used to go out on picnics often, alone or with others, carrying food and water bottles (of course we drank only boiled water, even on the mountain) in the bottom of

my chair. The bearers would sit and watch us eat, filled with wonder at our strange ways. One could see that they had a feeling of commiseration for us as they sampled our queer, cold picnic food.

Keeping food at such a place as the temple was most primitive. We bought a live fowl and perhaps kept it a day or two. Then the cook had to take it outside the temple to kill it; Buddhists do not take life, and our doing so (even off the premises) was only by courtesy of the head priest. We often had a chicken killed Sunday morning and ate it for our noon meal. In the hot weather it would not be safe to eat meat that had been kept overnight, so we tried to finish up such food at the first meal after the killing.

There were some newly arrived missionaries at Tawosze that year. They objected to our having chickens killed on Sunday. The wife came to me and talked long and seriously about how wrong it was to have such work done on the Sabbath; chickens should be killed Saturday if they were for Sunday dinner. I was distressed, but not as much as she hoped. I knew plenty of missionaries had their servants kill fowl on Sunday, so I told her I could not believe my attitude had serious moral implications. It was not a moral issue of the observance of Sunday; it was a necessity for the preparation of wholesome food. An old missionary lady who heard of our conversation took me aside later and told me to pay no attention to such talk. "Tend your own kitchen and foods supplies, and don't mix morals and hygiene." I have always tried to follow her advice.

In the early part of the summer we had a letter from our Chengtu gateman telling us that our house had been entered. The second-floor bathroom window had been broken and entrance effected thereby. The large chest of drawers which stood there had been forced open, in spite of its foreign locks, and evidently things were missing. We wrote to some of the Methodist friends who were in Chengtu during the summer. They visited our compound and discovered that our table linen was the chief loss. We blamed the cook who had been put in jail in May after the dollar robbery. He alone knew where I kept this linen locked up, and certainly he would know that we had left the city. A small alley along the rear north wall of our compound made it possible for a night prowler to scale the wall, about ten feet high, and drop into our tiny backyard far from the gateman, who lived beside our front gate at the extreme south of the compound.

All during 1907, Chengtu foreigners were more or less taken up with plans for entertaining the West China Missionary Conference, scheduled to convene in Chengtu in January 1908. Each Chengtu family would have to keep as many guests in their house as could be managed. In view of this, we had ordered two long Irish tablecloths. These had arrived just before we left for Omei; still unused, they had been locked away for the summer. At this time the Chinese were commencing to fancy the use of tablecloths at feasts

given by officials; our cloths probably became useful somewhere. I could never think of those cloths, and the other wedding linens that were lost, without keen regret.

On our Golden Summit trip that year we stayed an extra day at Nine Old Caves to take in more of the sights of the huge cliff under which the temple shelters. Early on the morning after our arrival, the face of this cliff was alive with monkeys, clambering about in the lush vegetation and chattering away at a great rate. This was a most arresting sight, and it was the only time we ever saw monkeys in their wild habitat in West China.

We took our teacher, Mr. Chu, for the stay on the mountain top. He enjoyed it, and Bob kept up his lessons. I had not the strength for study that summer and was forced to lie about, trying to win back my former vigor. I used to play chess with Mr. Chu, and we three took several rambles about the several summit temples. On any long trip I was carried in my chair. We had marvelous views of the incomparable snow mountains to the west.[1]

The priests remembered that on our arrival the year before we had immediately seen "Buddha's Glory," and they welcomed us with what seemed to be special regard. They gave us a pleasant suite of rooms. There was a good-sized guest room where Bob could study and where we had our meals, the Boy preparing them in our presence on a small charcoal brazier. Bedrooms opened off either side from this room; Mr. Chu had one, and we the opposite. It was so cool mornings and evenings that we were all glad of the brazier's heat. We spent more than a week at the summit; it was an interesting experience because through our teacher we learned more about the mountain and its temples than we had on our other visit.

On our return to Tawosze we had word from Chengtu that one of the teachers from the government university had been forced to move with his family into our empty house. There had been a big flood in Chengtu, and they had literally been driven out by the high water. This was truly a hard-luck family. The husband had given up a good teaching job in California for what seemed a very attractive offer: a good salary, house, servants, saddle horses, and other benefits such as free passes on the Szechwan railways. Prudently, he decided to proceed alone; his wife and four young children were to await his report before starting out to join him. Arrived in Chengtu, he found that not all was as promised. The housing was a couple of rooms on the campus, where no women were allowed; servants had to be trained; horses could be hired, for a price; and there was no vestige of a railway in Szechwan. But his first mail from America brought word that his family had grown impatient and were already on their way. This was in the spring when we were making over our own Chinese house. The husband anxiously tried

[1] Capping the view would be the 25,000-foot sharp pyramid peak of Minyagonga.

to persuade us to rent a part of it to him. Bob felt sorry for the family and would have agreed. Though it seemed hardhearted, I was firmly against it. The place was simply too small to add a family of six; we needed some peace and quiet for study, and our home was important in the work we hoped to do.

Eventually, the university found a small Chinese house for the teacher and his family. It was close to the university, but on low ground. When the flood came, they had to escape. The husband carried his wife on his back; the oldest son carried the little girl. Our house was the only place to go. We were thankful to be able to provide a refuge.[2] By the time we returned to the city, they had moved back to their own place, leaving our house in good order. Only our student lamp did not work. I found that their servants had used native oil. After a grand boiling and cleaning and a new wick, it resumed normal functioning.

We became friendly that summer with the old head priest of Tawosze and found him a pleasant, kindly old man, albeit with a remarkable shrewdness and ability to read character. Rumor had it that he had been a man of the world whose desire for a son had never been realized although he took several wives. Finally he decided that he must have offended Heaven, and so sought a priestly life. He had risen to be the head of Tawosze and had made it prosperous.

One of his money-making ideas was the renting of rooms and apartments to foreigners. Once when we were looking at rooms which we thought we might take, we both exclaimed over their age-old dirt and the truly amazing array of spider webs hanging from the rafters. The old priest usually left such affairs to a subordinate, but that day he was with us. He turned to the windows, whose lattices he had caused to be propped open to reveal a mountain scene of great beauty, and remarked: "Do you not come to Omei for rest and a view? Here you have what you seek. These other things do not matter." We once saw his private room; it was an appalling medley of personal belongings, utensils, books, dried medicinal herbs, stores of all kinds, and piles of extra bedding needed for pilgrims. It looked as though there had never been a housecleaning since Creation.[3]

[2] The family who took refuge in our home from the flood was named Larsen. Not long after this, they left Chengtu and passed out of our lives. By World War II the son, who had spent most of his life in China, became a non-Foreign Service employee of the State Department. I then met him for the first time. In the "Amerasia case" in 1945 he and I were among the six arrested. In the heyday of Senator McCarthy, guilt by association was elevated to new levels. An active group of Washington journalists developed the status of experts through the imaginative use of leaks and tips from persons with obvious access to FBI files. One of these triumphantly announced that Larsen and I had known each other and been associated since our boyhood in China. The association was two years before I was born.

[3] The old abbot's friendship with Grace and Bob probably reflected Bob's developing proficiency in spoken Chinese; as the years passed, it became noteworthy. I have heard Chinese insist that hearing him behind a screen they would not guess that it was a foreigner speaking. But it

was pure colloquial Szechwanese, which could astonish and amuse Chinese from other regions. Having to start out by rebuilding a house certainly helped. Also, it seemed to be against his nature to be with a Chinese—any Chinese—without engaging him in friendly, interested conversation.

The other "business" of the temple was the cultivation and sale of white wax. This is used to harden other waxes and commercial glazes and is quite an important export from Szechwan. It is the product of an insect native to an area southwest of Mount Omei. The insects lay their eggs on the young branches of a certain tree. At the right time the branches are broken off and boiled; the wax rises and is taken off in clean cake form.

The final processing of the wax was at the end of the summer. A large balancing scale was hung outside the old priest's upper temple room so he could see the weighing of all the temple wax. One day I took hold of the large hook and hung my weight on it. I was just seventy catties,[4] and this was after my summer of recuperation when people were all telling me that I looked well again. I wonder how I looked when I came to the mountain.

A short time before we left Tawosze we had been over to join the first meal in the new cottage of the Beamans at Hsinkaisze. This is now quite a resort with a community of foreign bungalows. The Beaman cottage was the first built there; but only shortly after they moved in, Mr. Beaman was taken ill. They left the mountain, packed up their Kiating home, and had to leave West China. We bought a few pieces of furniture from them, the chief being a handsome desk which had been built to the specifications of a former member of their mission.

From the Beamans we also acquired two fine cows. We also took on Lao Yang, their cow coolie who had been well trained by Mr. Beaman. He proved a quaint old fellow and was a fixture in our household for many years. His wife, whose face was shriveled like a dried nut, also helped with the cows. They spoke a thick, blurred Kiating dialect which often puzzled our ears. Lao Yang liked a nip of hot wine in cold weather for a pain in one leg. A year or two after the old man came to us, our cook wanted a wife; this gay and gallant old cow man took the part of go-between in the transaction.

[4] "Catty" is a Malay word. For reasons now forgotten, early foreign traders in China preferred it to the Chinese word jin . It was usually considered to be one and one-third pounds avoirdupois. Grace's seventy catties would thus be ninety-seven pounds. The imprecision is necessary because the Empire did not concern itself with mundane commercial matters. The merchant guilds in each major trading city established their own standard weights and measures. Furthermore, the jin (or catty) could vary according to the commodity to which it was applied: a catty of tea, for instance, could be less in weight than a catty of coal. This imprecision caused the Encyclopedia Sinica (Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh, 1917) to conclude: "It does not seem to be of much use therefore to give a Table of Weights and Measures" (p. 596). The Republic officially adopted the metric system but lacked the power to implement it. In the People's Republic the metric system is universal, "catty" is no longer heard, and a jin is one-half a kilogram (or 1.1 pounds).

We had so appreciated the beautiful flowers and shrubs on Mount Omei that we took back to Chengtu a number of roots and bulbs. Our Boy, devoted to plants, was the one who suggested the idea and he zealously did the collecting. Among the gains for our Chengtu garden were regal lilies, which grew marvelously for us, huge hydrangeas, and yellow-flowered terrestrial orchids.

11

Open House Days

(1907-8)

When we left Kiating that September we hired a cargo boat with a high peng (a rounded mat roof) and a good wooden floor. The Boy had gone with us as cook to Golden Summit and did so well that we now discharged the dirty cook at Kiating, giving him travel money. The hold of our boat was loaded with loose dried beans which looked to be a clean and non-odorous cargo. We put all our things on the floor level, and the boat was large enough to give plenty of room and, best of all, good head space. Our teacher was with us on the boat and we studied as we traveled. We could even sit at our new desk to study and write. The trip to Chengtu was expected to take about a week.

The floods that summer had caused damage along the river and we saw signs on every hand. Once, walking on the bank, we noticed tangled vines above our heads in tree branches. These were peanut vines that had been washed out of the fields and lodged in the trees. Even at Chengtu the river had covered the big stone bridge outside the South Gate. Close to this place, a big section of the city wall had been undermined (and took many months to repair). But, despite the summer flood, the river was now rather low for that time of the year—and our boat was large.

Life was very pleasant for the first two or three days, and we congratulated ourselves on the size and comfort of our craft. Then trouble began. At first we found only a few tiny white worms. In a few hours they had multiplied and were into everything: food boxes, beds, clothing, even into our ears when we took refuge tucked tightly inside a bed net. The little worms were everywhere. Complaints to the captain were useless; worms meant nothing to him. We then tried to hurry the boat, but its draft was considerable and the river seemed to be falling. We could only proceed by the main channel and frequently had to wait for other boats to negotiate narrow spots. After a couple of days of worms, we began to have a pest of little white moths. The

worms were busying themselves in their life cycle under our very eyes. These tiny blundering creatures flew everywhere, and our tempers were decidedly on edge.

I began to feel that we would never reach Chengtu, and the eternal singsong of Bob repeating Chinese phrases after his teacher's intoned speech made me weary beyond words. To be honest, 1 yeas probably as much of a trial to live with as the worms and moths! Bob suggested that from a village about a hundred li from Chengtu,[1] I could reach the city in a day in my chair, the Boy escorting me. But when we reached the village that evening, it was impossible to find chair men. Next morning it was raining, which ruled out the possibility of making the trip in one day even if bearers could be found. So I settled down to sticking it out on the bean boat. We had still more trouble, having to lighten cargo at one place where the channel was shallow and the current swift. We did not reach Chengtu until the next Tuesday. Then there was a joyous farewell to that nice, clean boat full of its worms and moths with whom we had spent eleven unforgettable days.

We were delighted to reach our Chinese home again. A quick check showed that the robbers had taken practically all my table linen as well as some other things. Otherwise all was in good order. A few days of scrubbing, washing windows, hanging clean curtains, and changing shelf and drawer papers made us as clean and fresh as could be. I liked the new desk very much and had it set up in our living room, where it became my special possession and delight. Bob had a large Chinese desk of red bean wood in his study, so he did not need it. My new desk was of what was called "buried nanmu."[2] It had a large flat top. On each side above the table top were six small drawers. Between these stacks an open space was just right for a row of books. Below on either side were tiers of large drawers. Many and many a letter I wrote on that desk, and many that I received were stowed inside.

That fall we studied, and continued to widen our acquaintances among Chinese. Bob spent much time and thought making plans and establishing contacts with people. An advisory committee was formed as a preliminary step toward the organization of a full-fledged YMCA. Sunday afternoon meetings were held, sometimes at our house, sometimes at the Hodgkins'.

[1] Ali is generally considered to be approximately one-third of a mile. But when all travel was by foot, precise distance was not as important as a measure of time and effort. The rhythmic flexing of a shoulder pole with a load suspended from each end (or the bamboo poles of a sedan chair) produce a brisk, slightly bouncy stride. Traveling on the level, this standard pace would cover ten li in an hour (on the major roads, this would bring them to a teahouse). Hence the one-third of a mile approximation. But on hilly roads the li could be one-fourth of a mile, or even shorter. Quite consistently, the same distance could be twenty li if one was going uphill, and perhaps only ten li if one was going down.

[2] Nanmu (Machilus nanmu ) is native to West China and was considered to be one of most valuable and beautiful of Chinese timbers. The best trees were reserved for imperial use, often for pillars of the largest temples and palaces. It was also prized for the finest coffins.

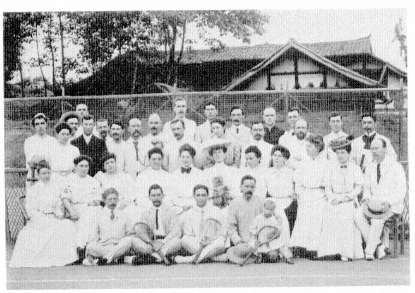

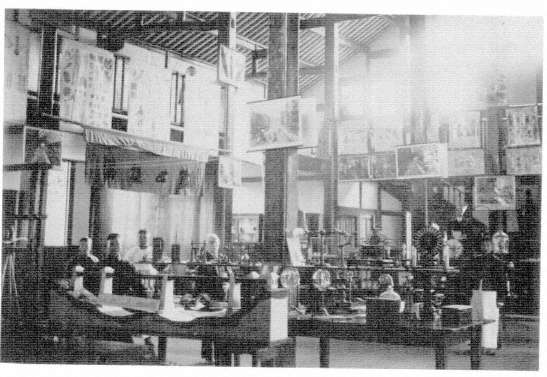

15

Tennis teas were an important part of Chengtu social life. One man here

managed to play in a Chinese gown. (Probably in 1908.)

I was still miserable with my severe pain and suffered exceedingly with backaches which wore me out. My cook could not make good bread, and there were no bakeries whatsoever. The bread, rolls, cakes, and cookies all had to come from my hands. For ourselves alone, this was not much; but we entertained Chinese constantly, and they were all pleased to have foreign-style refreshments. Late that year I finally got our new cook, who had been our Boy at Omei, trained to make acceptable cookies and cupcakes. This was a great help. Tea had always to be served to our guests. If they did not eat the cakes served with it, these were gladly pocketed to be taken home to a small brother or sister, to children, or even to a mother interested in sampling the odd things served by the Westerners.

About that time we rented a piece of land at the rear of the Methodist school adjacent to us on the west. It belonged to the mission but was then not needed. It gave us space for two tennis courts with a tea pavilion west of them in the shadow of a high wall. There was also some ground left over for raising vegetables. Eventually we enjoyed many products of our own garden.

Our young friends among Chinese students began to ask if I would call on their families or be at home to receive calls from them. Doors thus opened in both directions, and we became deeply involved in our surroundings. I began to teach English to a few young men. At first my work was individual instruction in conversation and composition. Our careful attention was given to the young man who was later to become the first Chinese YMCA secretary

in Chengtu.[3] In 1907 I did not keep a careful record of the guests at special teas we had for Chinese students, but I know the total ran into 600 or 700. For 1908 I did keep a weekly record. It gives a total of 967 as counted. However, on numerous occasions we were not able to count late comers, so our figures would read "42 plus" and so on. Also these records showed only those who came to our regular, announced teas. Bob had many individual callers in both those years; in 1908 he doubtless entertained well over 1,200. These contacts were valuable to him and gave me considerable to oversee and manage.

When Chinese women called, I had to drop everything. They often came at inopportune times for us, as Chinese meal hours were not the same as ours, and they would stay and stay and stay. To come at ten in the forenoon, or even around noon, and then sit until three in the afternoon was asking a good deal of a hostess, but we had to conform to the habits of the country. A lady often brought a whole train of attendants: perhaps a sister or two, several grown daughters or younger children, and often four or five amahs. The guests sat down to visit, and the servants stood around gazing at everything and being what one might call movable fixtures in the room. It took me a long time to accustom myself to these calls. Gradually I learned the technique, and despite my lack of adequate language could carry them off with some sort of aplomb. I learned the polite phrases, and could fall back on the children and stock questions. Eventually, some of the women became my real friends, so that barriers no longer made such a chasm between us.

All women guests wanted to see our entire house. Most of them, if they expressed any opinion, thought we wasted too much time trying to be clean: clean kitchens and clean floors were no necessity to them. When I visited their homes, I was impressed by the dirty kitchens and their lack of any adequate attention to the floors. Their kitchens were in what we would call sheds. Most of their floors were dingy brick or grimy wood. Frequent expectoration, together with the habit of allowing babies to urinate freely on the floor anywhere and everywhere, made for unhygienic conditions and offensive odors. Cobwebs never seemed to bother Chinese; to this day I have to call servants' attention to them. Upper walls and ceiling spaces seem never to come within range of the Chinese eye; special orders must be given if you want to be sure that high corners will be cleaned. On the other hand, Chinese take great care in polishing the fiat top and side surfaces of furniture such as cupboards and sideboards; and a Boy will carefully dust framed pictures every day, sometimes even dusting behind them.

[3] The YMCA has always referred to its higher-level salaried personnel as secretaries. The term includes executives, administrators, and program directors. It is, therefore, quite different from the secretary who is an office or clerical employee. Bob, for instance, was always a secretary.

Another of my household duties at this time was my husband's collars. Men were still wearing stiff collars every day. It seemed impossible for the Chinese to get them stiff enough, or to keep from scorching them during the ironing. And there were no tailors in these early years who knew anything about "foreign-style" sewing. So what sewing I needed, I also did myself, by hand and machine. I sent for American patterns and made clothes as I could, studying the illustrations of magazines and inspecting the clothes of new arrivals from home. It was my boast that I could cut out a man's shirt one evening and have it finished, save buttonholes, by the next afternoon. I learned to stitch such pieces without any basting and thus could save time. I taught my amah to do buttonholes. Her first attempts were what my New England grandmother would have called "pigs' eyes," but Amah improved and became a fine buttonholer.

I was busy during these early Chengtu days. Often I rose at 6:30 in the morning to work down my bread. Then there was study, sewing, and general housekeeping. This could include a lot of mold prevention, and packing away all woolens and winter things at the approach of hot weather. Dry cleaners were unheard of, and laundry work demanded much attention and training of servants. It is quite a task to do up men's white summer suits, be they duck, silk, serge, or flannel. I found the Szechwanese to be good washers but poor rinsers. It was my rule to demand ample water for that use. By this means I kept our clothes from taking on that dull, muddy tinge which many housewives regard as one of the prices of living in the Orient.

Late in 1907 the West China Missionary Conference was impending, and I was determined to find a Boy who would be wide-awake and efficient. I interviewed several prospects without success. At last a young fellow named Liu Pei-yun appeared. I had never wanted a country boy, because it seemed to me that some education, however little, would hold more potential for training. This boy was the son of a buyer of silk yarn. He could read and write and was an apt pupil in learning the work expected from him. On arrival he knew nothing whatsoever of any foreign furnishings or usages. When I first showed him how to set the table, he asked what the forks were and how they were used! He became a trusted servant, was married in our home, and worked for us from the fall of 1907 until that of 1920. Bob then helped him set up a business for himself in Chengtu. In later years he visited us several times in Shanghai and has always kept up connection with our family.[4]

In January the long-planned conference was held. As all the out-of-town people had to pay their own travel expenses, we Chengtu residents were ex-

[4] Liu Pei-yun's service to our family gradually went far beyond the role of cook. I remember him, for instance, far better than the amah who tried to look after me. The business venture, though, had an unhappy ending—but that comes much later.

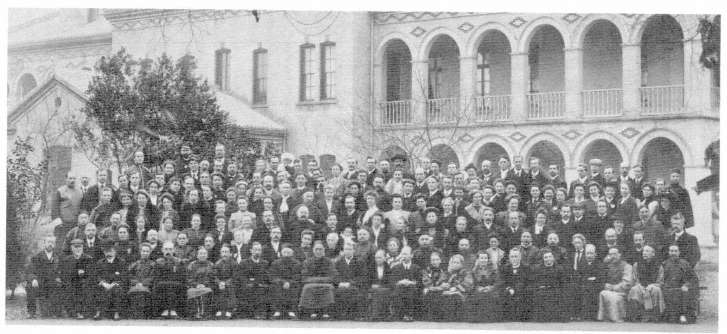

16

The West China Missionary Conference at Chengtu in January 1908. The building Was the justcompletedhospital of the (American)

Methodist Episcopal Mission. Though Chinese garb was popular, thereappears to have been only two or three Chinese present—and

their positions at the extreme peripheries,right and left, leads one to wonder about their status. Grace and Bob are at the upper right-

hand corner: she with a rather large hat, Bob just behind her with only the top of his face showing.

pected to share by providing free accommodations. Bob and I moved into the ground-floor room behind our living room, giving our bedroom to Charlie and Robina Service of Kiating with their three little girls. Our other upstairs bedroom at the other end of the house was occupied by Dr. and Mrs. Tompkins of Suifu [now Yibin]. A room connecting with the dining room and kitchen, generally used as an ironing room and a place for drying clothes by charcoal heat (often necessary in our Szechwan drizzle), was transformed into a bedroom for two more visiting men.

Of course we did not have this many beds. We used camp cots ourselves. For the guests in the lower room we borrowed two slit-cane bed frames laid across benches. Heavy cotton pugai were quite satisfactory in lieu of mattresses. All the guests came with their road bedding, so there was an abundance to keep us all warm.

The conference was held in the newly completed Methodist hospital at the Shansigai compound.[5] As some of the attendants were too far from their lodgings to return for the noon meal, their hostesses had to send lunches to the conference building. Also, many were British and devoted to their afternoon tea in a way not always understood by Americans. This had also to be served daily, and made much work for many faithful Marthas, who had little time for the enjoyments of the Marys who could attend all the meetings.

Since our house was relatively near—less than fifteen minutes' walk from the Methodist compound—our guests returned for lunch. Often there were four or five extras. With these, our nine house guests, and ourselves, it made quite a gathering. It was a strenuous time for our kitchen staff and equipment. I had previously arranged with Robina Service that her efficient cook would do all the baking. He turned out bread, rolls, muffins, cookies, and cakes in abundance and took a great load off my shoulders. My cook had his hands full with the other items of our daily needs. We had laid in potatoes from Kiating (hard to get in those days) and had made mincemeat and pickles.

About two hundred and fifty people attended the conference, and it proved to be an interesting and worthwhile gathering. Among speakers from afar were Mr. Sloane of the China Inland Mission and Dr. Arthur H. Smith of Shantung. Mr. Pollard of Yunnan, though of our own West China region, had to travel for as long as any of these to attend. Dr. Shelton and Mr. Ogden came with their wives from Tatsienlu on the Tibetan border, where they had been studying Tibetan in preparation for their move to Batang—thirty days

[5] The hospital where the conference was held was a very solid brick building of three or four stories. Its sturdy construction, and the fact that its surroundings were all low, led to its being used as a fortress by one of the armed Red Guard factions during the violent phase of Chengtu's Cultural Revolution in 1969. When I first returned to Chengtu in 1971, it was surprising to see this old mission landmark bearing heavy scars of rifle and artillery fire.

in toward Lhasa from Chengtu. All five of these leaders have now [1937] passed on.

It was a rare treat for us to see so many foreigners and to meet people of whom we had heard. To me the most inspiring talk was one by Mr. Pollard, who followed his address by presenting several Miao tribesmen who had accompanied him to Chengtu. These rather rough-looking fellows sang in their own tongue the hymn "Washed in the Blood of the Lamb," making a great impression by the evident longing and sincerity in their hearts.

On the last day of January there was much excitement over the visit of the viceroy, His Excellency Chao Erh-feng. The next day was the last of the conference, and Bishop Bashford gave the closing address in the afternoon. A group photograph was also taken that day. The same evening we entertained Dr. Arthur Smith and others for dinner. On the following Sunday, Bishop Bashford conducted a dedication for the new Methodist hospital, which had already been the conference site. This ceremony closed with the celebration of communion.

The next day guests began to leave. To the hostesses this meant providing each party with a cooked roast (beef or several fowls) and plenty of bread for their road boxes. The Charlie Services stayed on with us for their own mission conference. Their baby, Frances, was quite ill for a few days, and I helped her mother prepare whey for her diet. Winifred, the oldest child, had her fifth birthday during these days; we fixed a cake with candles and got up a small party with the Canright children as guests.

Our good friend Dr. Florence O'Donnell was now getting ready to leave China after a five-year term of service. She had become engaged to a man in her home, Nova Scotia. Great was the sorrow among her friends, both foreign and Chinese. For many years we were constantly asked about her welfare. One day before she left, a group of us, including the H. D. Robertsons and Mr. Fox (the British consul, later Sir Harry) took a ramble to some property outside the South Gate which had just been acquired as a site for the West China Union University. We sat on graves there and wondered what our surroundings would look like in a few years. Some one hundred and fifty acres are now the attractive campus of this thriving university. The buildings, trees, shrubbery, and grass have entirely changed the looks of those fields and grave mounds.[6]

The American community grew slowly. Late in 1907 another young Californian, C. W. Batdorf [UC 1906], had come to teach in the government uni-

[6] During China's Resistance War (1937-45), the West China Union University gave refuge to several leading Christian universities from East China cities occupied by the Japanese. Thus it became, along with Kunming, where the principal government universities found refuge, one of the two leading intellectual and academic centers of China during those war years. Today it has become a much enlarged medical university and dental school. But the local people still refer to it by the old name, Huaxiba (West China campus).

versity near us. He and Mr. Bullock [also UC 1906] kept bachelor's hall together. We were always glad to help them when we could; I made curtains, sheets, and such items for them. Early in 1908, Chee Soo Lowe, a California-born Chinese who had graduated in mining from the University of California [still another member of 1906], came to investigate the mineral resources of Szechwan under employment by the viceroy. He was often in our home and we greatly enjoyed him.

As the Chinese ladies became less bashful I began to have more callers. Many of them besought me to start some sort of classes for them. They wanted to "learn foreign ways," to knit, crochet, and even to bake the light cakes which they ate in our homes. We were constantly invited to Chinese feasts. Here the procedure is the reverse of our custom. Chinese socializing is done before the meal, and the guests leave directly from the table: This meant that we often sat talking while the very food we were to eat was in preparation. We might hear the fowls squawking as they were chased and killed to be served to us later. The men and women always ate in separate rooms: the men in the main hall or some such public apartment, while we women were relegated to women's bedrooms. I was teaching a few pupils and kept busy in spite of not being well. I still had my attacks of severe pain now and then and was forced to spend a good many days in bed.

12

Journey to the West

(1908)

My health was a problem; the doctor thought it might even necessitate my return to America. Such a prospect seemed terrible. I was devoted to our enterprise. I could see with what devotion Bob threw himself into work with young men; it was his very life. I felt I also had a share in it. And we had both learned to love China and the Chinese friends with whom we came in close contact in Chengtu. It was thought best for us to try a lengthy vacation in as different an environment as possible.

It seemed that this summer of 1908 would be our last chance to vacation at any considerable distance from Chengtu. In another year, we expected, the Chengtu YMCA would be organized and require Bob's attention; Mount Omei would be too far away. But for now, we had been to Omei the last two summers and were ready for something new. Furthermore, the elevation of 2,700 feet at Tawosze temple did not give much of a change from the 1,700 feet at Chengtu. Our eyes turned toward the Tibetan border. Here we could be among high mountains in a much cooler and more invigorating climate. Our Chengtu friends, the R. J. Davidsons, had gone in with a small party to Tatsienlu in the previous summer.[1] From them we learned about the trip and the equipment needed.

The spring was a time of preparations—in addition to our usual affairs. The Sheltons and Ogdens, whom we had met at the conference in January, were in Tatsienlu getting ready to move on to Batang, a big step forward into Tibet. Fortunately for us, the Ogdens stayed when the Sheltons moved on. The only other foreigners in this remote town were the Sorensons of the China Inland Mission and occasional game hunters and plant collectors who passed through on their wanderings.

[1] Tatsienlu is now known as Kangding.

We wrote to the Ogdens for help in planning and could scarcely have arranged our camp without their friendly and thoughtful help. In Chengtu we had new folding camp cots made from a British army model (sewing the canvas tops was very difficult without heavy equipment). We also made new folding chairs, which added greatly to our comfort in camp. Bed nets had to be remade, and several butterfly nets were prepared. Bob had become keen on that hobby and wanted to see what new trophies he might find in higher altitudes. Our supplies were all carefully chosen. We had road boxes of galvanized-iron made. Even though the lids fitted tightly, they were—to our regret—not entirely watertight. Cuts had to be made in the metal sides to attach carrying rings; if a box fell on its side, water could enter. However, they were sturdy and served us well, many of them until we left Szechwan many years later.