Learning to Dispute

Appearing with the twelfth-century schools, the magister occupied a prestigious position in the rarefied milieu of the literate clergy.[22] And with the foundation of the universities in the thirteenth century, he

grew to be an ever more prominent figure.[23] His official title distinguished him as an authoritative scholar who presided over the canonical texts. At the same time, the licentia docendi invested him with a specific pedagogical responsibility. The master was in charge of instructing groups of student-disciples and of initiating them in a world of scholarship. This initiation staged a confrontation of wills that was to culminate in the disciple bending to the master. According to the popular clerical manual De disciplina scholarium : "He who has not learned that he is subjugated [to the masters], could never come to know himself as master" (qui se non novit subjici, non noscat se magistrari).[24] In vernacular descriptions as well, the master/disciple rapport develops out of a sense of rivalry and respect. A late-thirteenth-century didactic work, the Livre d'Enanchet portrays just how charged that rapport is:

Et si-l doit metre ainz au boen meistre q'au mauvais, por ce que-u boens meistre est mout utel chose au deciple. Et il doit sorestier a la dotrine son maistre; por ce q'ausi corn la grotere de l'aigue chaant [chaut] d'en haut cheive la piere dure, vance l'usage a savoir ce que-u cuers de l'ome ni voldroit maintes foiees. Mes il doit mult honorer son meistre, por qu'il est lo segond signe de science, et doit mult enquerir sa dotrine et noter ses paroles et son chastiemant.[25]

And he should dedicate himself to a good master rather than to a bad one, since a good master is extremely useful to a disciple. And he should attend to the doctrine of his master, for just as a drop of water fallen from above pierces the hard rock, so too the use of knowledge hits a man's heart where it is oftentimes not receptive to it. But he should greatly honor his master, since he is the second sign of knowledge and he must seek energetically after his doctrine and take note of his words and teaching.

As "lo segond signe de science," the master embodies the world of learning (dotrine ), outfitting the disciple for an intellectual life. Yet that preparation involves yielding to the master's authority as well as to his knowledge. The Livre d'Enanchet shows the master handing down a chastoiement . This Old French term, echoing the Latin castigare found in the Disciplina , combines the notions of instruction and latent strife: one goes with the other. Imparting a doctrine entails a type of castigation or chastisement. This castigation was directed toward both men and women; contemporaneous didactic texts such as Le Chastoiement d'un père à son fils and Le Chastoiement des dames are built on one and the same model of the master taking the student in hand.[26]

This sense of discipline discloses the tensions informing the master/ disciple relation. While the disciple struggles to attain the master's respect and wisdom, the master in turn castigates him. Contention fuels their exchanges and, paradoxically, binds the two figures together. If the surviving accounts give us any indication, such contentious relations ruled university life.[27] Even the latter-day humanist critic Vivès would describe the scene as all "that scholastic shadowboxing and contentious altercation" (scholasticasque illas umbratiles pughas et contentiosas altercationes).[28] The medieval master inducted the disciple in an intellectual life whose characteristic methods were conflictual. The question-and-answer modes of instruction (quaestiones ), the disputations (disputationes ) that began the debates pitting masters against students (quodlibeta )—such standard dialectical methods trained the student to work against his master.[29] If the disciple was ever to assert himself, he had to proceed adversarially—in John of Salisbury's words, through "verbal conflict"—mounting challenges and refutations of what the master put forth.[30]

These challenges were never meant to jeopardize the institution of mastery. On the contrary, the entire agonistic process was geared to outfit the disciple for the master's role.[31] It distinguished those few disciples who would eventually assume the magister title from the many others who failed to meet the test. The sustained disputations sanctioned certain disciples as members of the scholastic elite. In the end, the chastoiement validated them as authorities able to discipline others. In this, the master/ disciple engagement resembles the sparring between knights, for there too the clash provides a mechanism for bonding that secures both men in the same courtly, chivalric roles.[32]

No more telling example of the disputational dynamic exists than the case history of Peter Abelard. The dialectical method of thought that he pioneered in his treatise the Sic et Non was illustrated uncannily in his own dealings with his peers: his unceremonious rejection of his master, Anselm of Laon, his attacks against a rival master, William of Champeaux, his sparring with his own followers. Abelard exemplifies the way the medieval system of intellectual mastery functioned by creating conflict so as to better establish control of intellectual problems. The difficulty in mastering a particular body of knowledge was played out through disputation. And far from dividing the masters and students definitively, their disputatiousness acted to consolidate their caste. The more bitterly they fought among themselves, the more tightly they closed ranks and cemented their control over intellectual matters. Abelard's reputation makes this clear. However he depicted himself as renegade and outcast, medieval posterity identified him as one of the masters' own.[33]

Abelard's case is also important because it reveals how the feminine begins to inform the disputatiousness of medieval masters and disciples. Intellectual traditions in Europe had long typed knowledge as a woman (scientia ), and its highest form, wisdom, as a female deity (sapientia ). Like many other masters straight on through the Renaissance, Abelard dedicated himself to the goddess of wisdom, Minerva. "I gave up completely the court of Mars so as to be brought up in the lap of Minerva. . . . I put the conflicts of the disputation over and above the trophies of combat."[34] Abelard's description of his entry into intellectual life gives us a telling sense of how the pursuit of knowledge is connected with the feminine. Embracing wisdom implies coming into contact with a woman. Yet this embrace is not incompatible with aggressive impulses. Although Abelard renounces the god of war, he does not relinquish the martial arts. For him, the bellicose and the feminine come together in the form of the disputation. Under the aegis of Minerva, verbal battles are to be waged. That Abelard chooses this goddess as mentor shows how the scholastic activity of disputing comes to be figured through women.

But if intellectual mastery is represented in part through the feminine, where do women figure in? We come back to the question of women's encounter with clerical intellectual life. Can they participate in the master/ disciple disputation? Abelard's explosive experience with Héloïse hardly bears this out. His tutelage of her was short-lived, leading quickly to their sexual relation. In the vernacular domain, the picture is little different. In the Livre d'Enanchet , for instance, the master who debates with his disciple puts forth the following doctrine (la dotrine dou clers ): "It is better to sit in a corner of the house that is not in the throughway; not like a woman who wags her tongue" (il est mieuz seoir en un angle de sa maison qe n'est en chiés comun. Ne corn famme laengueice! Fiebig, 7).[35] This portrait of the model clerk distinguishes him from the woman who talks too much. And it spatializes his distinctive role. Whereas the woman plants herself in the middle, the clerk is recommended to place himself apart, in isolation. Such a scene, I would suggest, builds on the standard outline of the social hierarchy of roles in Andreas Capellanus's De amore : "In addition, among men we find one rank more than among women, since there is a man more noble than any of these, that is, the clerk" (Praeterea unum in masculis plus quam in feminis ordinem reperimus, quia quidam masculis nobilissimus invenitur ut puta clericus; II, 1; Parry, 36; Pagès, 10). The fact that the clerk inhabits a separate space underscores his unique position. Not only does he represent the "most noble" man, but he has no female equivalent. In the clerical schema of Capellanus or the Enanchet , there are few signs of women assuming the stance of disciple.

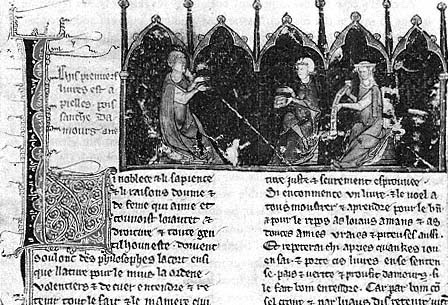

4. The duke and duchess of Brabant and the master of the Consaus d'amours .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 2621, fol. 1.

Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

Such definitions of clerical life give us a first glimpse into the vexed position of women vis-à-vis intellectual mastery. They are at odds with the clerical role. Yet they are not completely evacuated from its domain. The inaugural miniature from the Consaus d'amours , a late-thirteenthcentury didactic treatise, exemplifies this dilemma (Figure 4). The woman, the duchess of Brabant, sits side by side with her lord the duke—an apparent partner in the lessons the master pronounces.[36] But the text that follows relays a debate engaging the men alone. Designed implicitly as a master/ disciple dialogue, it leaves little room for her. In fact, the insignia of the various figures in the miniature confirm this: while the book links the duke to the academic learning of the master, the scroll identifies the woman with the oral. The duchess appears ready to repeat the master's formulas but unable to engage with them fully and make them her own. The structure of the master/disciple dispute seems to both accommodate women and disqualify them.[37] While included theoretically as part of the proceedings, they are nonetheless blocked from participating in its work: mediums of the disputation, yes; real contestants, no.