2—

In actual practice pictorial perspective is a rather unscientific mixture of theory, experiment, and artistic convention, and I will go no further into the subject than seems absolutely necessary to demonstrate the role played by perspective in the presumed correspondences between visual perception and image making. For this purpose, the brief definition of

perspective offered by William Ivins in Art and Geometry is sufficiently precise and uncontroversial:

Technically, [perspective] is the central projection of a three-dimensional space upon a plane. Untechnically, it is the way of making a picture on a flat surface in such a manner that the various objects represented in it appear to have the same sizes, shapes, and positions, relatively to each other , that the actual objects as located in actual space would have if seen by the beholder from a single determined point of view.[12]

From the Italian Renaissance onwards, artists learned to envision that plane or flat surface as being like a plate of glass or even an actual window on which could be seen a proportionately scaled-down replica of the things in front of the glass. In Leonardo da Vinci's words, "Perspective is nothing else than the seeing of an object behind a sheet of glass, smooth and quite transparent, on the surface of which all the things may be marked that are behind this glass; these things approach the point of the eye in pyramids, and these pyramids are cut by the said glass."[13] What the artist does, in principle, is copy the image produced where the glass intersects the "pyramids," duplicating (to the degree his or her materials and skill permit) the exact shapes, colors, and shading seen there. Or as Alberti puts it, "A painting will be the intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance, with a fixed center and certain position of lights, represented artistically with lines and colors on a given surface."[14]

Leonardo and Alberti (like most Renaissance theorists of perspective) conflated the perceptual and the purely optical aspects of perspective.[15] They talked about images as if they were explaining concepts in geometry and mathematics. Vision became a question of "lines" forming "pyramids" that converged on a "point" in the eye, and painted pictures were simply larger versions of the picture produced by the same "pyramid" within the eye itself. Thus, the rules of perspective and vision seemed to complement each other and in both cases rested upon the principles of geometry and optics.

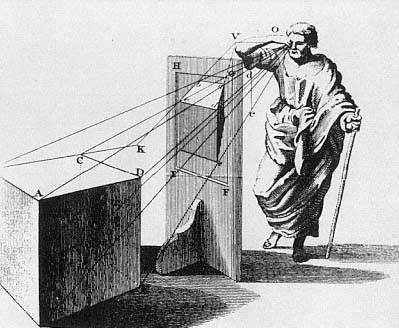

This meant that illustrations explaining the theory and practice of perspective were, at the same time, explanations of vision. They were, in effect, visualizations of sight that revealed—unintentionally—that a too literal application of the theories of perspective imposes peculiar limitations on understanding vision as well as on the possibilities of image making. The eye of the observer (the artist in this case) had to be an absolutely fixed point toward which all visual rays converge. The rays are represented with lines connecting the eye with the object of its regard, and

A demonstration of pictorial perspective: the plane E-F-G-H intersects

the visual pyramid whose base is the cube and apex is the viewer's eye.

From Brook Taylor, New Principles of Linear Perspective (1811).

where the lines pass through the artist's intersecuting plane, they define points corresponding to each line's point of origin. Alberti describes it this way: "We may imagine the [visual] rays as though they were very fine threads tightly bound together in a bunch by an iron band within the eye . . . almost like a pollard of all the rays, the node of which shoots its young branches straight and fine against any opposing surface."[16]

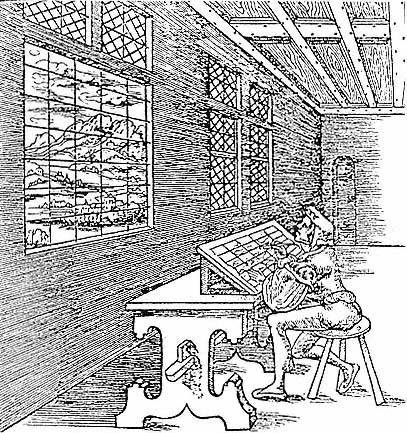

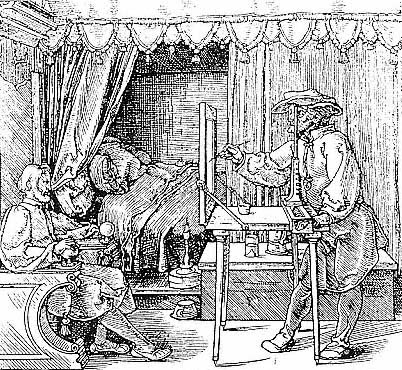

An illustration by Dürer shows an artist actually stretching strings from the object to the picture plane, but more normally artists covered the plane with a rectangular grid through which they looked at the objects from a fixed point of view—sometimes with the aid of an actual eyepiece mounted in front of the picture plane. The grid defined the hypothetical points where lines of the visual pyramid intersected the picture plane. With these points as guides, the artist could scale down the three-dimensional objects and situate them relative to each other on the two-dimensional surface of the picture.

Producing a picture by these means was like catching images in a rigid

Corresponding grids on the window and the artist's picture plane help

the artist to reproduce images seen on the plane created by the window.

From Johann II of Bavaria and Hieronymus Rodler, Ein schön nützlich

büchlein und unterweisung der Kunst des Messens (1531).

net strung across the space between the observer and the objects observed.[17] No matter how complex or ambiguous those objects might be—in form, spatial relationships, or emotional impact—they were caught in the same geometrical net and seen and depicted within the same rigid framework. Guided by this mechanical system of grids and immobilized points of view, the artist could (in the words of William Ivins) "substitute something that was rational and objective for something that was irrational and subjective."[18] What painting seemed to gain in realistic accuracy, it lost in what André Bazin called "the expression of spiritual reality wherein the symbol

The artist's eyepiece assures the fixed point of view necessary for

correct perspective. From Albrecht Dürer,

Underweysung der Messung , 2d edition (1538).

The fixed, peephole eyepiece and transparent screen offer the artist

a view much like that offered by a camera's viewfinder.

From Albrecht Dürer, Underweysung der Messung , 1st edition (1525).

transcended its model." Hence, for Bazin, "perspective was the original sin of Western painting."[19]

Not everybody has shared Bazin's pessimistic (and moralistic) views of perspective in painting, but most now agree that Renaissance perspective represents a special and limited interpretation of the visual world. It is, as Herbert Read has put it, "merely one way of describing space and has no absolute validity."[20] The Renaissance theory and practice of pictorial perspective encouraged an implicit equation between seeing and picture making based on the presumption that vision operates according to the same rules that artists follow in producing pictorial perspective. In Bazin's words, "The artist was now in a position to create the illusion of three-dimensional space within which things appeared to exist as our eyes in reality see them."[21] It is upon this basis that one can discuss a picture as a visualization of sight, in the primary sense proposed at the beginning of this chapter.[22]